You know it’s been a long, strange evening of dance when the sight of people jogging, playing ball, or even dozing in Riverside Park the next morning comes as a sudden, overwhelming restorative. Look, real people! Human bodies doing all those wonderfully human things that human bodies do! They’re not robots, they don’t light up in the dark, and they don’t blot out their personalities in favor of becoming anthropomorphic cartoon shapes. In other words, they’re not Nikolais dancers. I love them for that.

To be fair, the dancers who recently completed an all-Nikolais run at the Joyce aren’t Nikolais dancers either. They’re members of the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, a Salt Lake City troupe with a large and varied repertoire that has always included works by the late Alwin Nikolais. To mark the tenth anniversary of the choreographer’s death, his company’s longtime artistic director, Murray Louis, passed the torch to Ririe-Woodbury for what’s being called Nikolais: A Celebration Tour. Nikolais’s huge output is represented by works from 1953 to 1987, and these capable dancers honor the assignment pretty well.

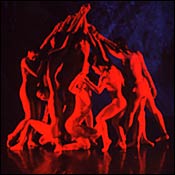

Nikolais has often been termed a genius—and five decades’ worth of enthusiastic audiences around the world would surely sign on to that assessment—but genius seems the wrong category for these particular innovations. Essentially he used technology to create startling effects onstage, with dancers reduced to design elements. In Liturgies, the dancers are spindly creatures who run in circles under a lighting scheme that transforms their shapes and colors as they go. In Crucible, we watch a long row of figures seemingly perched on a shelf, creating a spectrum of images that change while they’re flooded over and over with different colors. In Tensile Involvement, dozens of streamers criss-cross the stage … and so on and on.

Nikolais himself always took complete charge of realizing his vision: He came up with the costumes and lighting, and he was creating his own electronic scores long before most of his peers had ever heard of synthesizers. But whenever he tried to place dancing at the center of the spectacle, his imagination dried up. The choreography is limited and derivative; indeed, some of his work from the fifties borrowed so heavily from Martha Graham, I’m surprised she didn’t sue. His Noumenon Mobilus (1953) starts with two seated dancers covered in stretchy fabric who proceed to do exactly what Graham’s famous mourner in Lamentation was doing 23 years earlier. If Nikolais was a genius, it wasn’t in dance, it was in son et lumière. I’d love to see what he would have done with the Thanksgiving Day parade—which is just where the “Celebration Tour” belongs. Don’t get me wrong: That’s a compliment.

American Ballet Theatre presented a slew of premieres during its fall season at City Center, but only one was a keeper: William Forsythe’s luscious and brainy workwithinwork, set to Luciano Berio’s double-violin Duetti. Created in 1998 for Ballett Frankfurt, the piece is constantly fired with ideas: You can see emotions being let loose everywhere among the arch, slinky combinations and the spree of angled limbs, yet there’s not a moment of visible acting. Two women work busily on their points as if trying them out; a man pulls a couple of women on a diagonal across the stage until they split off to do big, ardent swirls and curves on their own; a line of men prowls forward in a low, sprawling walk that could have been drawn by R. Crumb. What holds it all together is the Berio score. Forsythe is musical the way Balanchine was: The choreography and the music seem to be inspiring one another at the very moment we’re watching, and we’re continually enlightened about both.

Other acquisitions include two idiotic works by Jiri Kylian, Petite Mort and Sechs Tänze, both with the same joke: hollow black ballgowns that slide around on wheels. As for Robert Hill’s new Dorian, based on Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, this endless, stilted melodrama is so much like a silent movie that every scene begs for a pounding organ accompaniment. I stopped taking notes around the time the action shifted to an opium den, where dancers dressed as lowlifes stood puffing their way to oblivion while the rest of us looked on longingly.