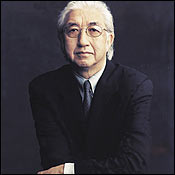

“The model for MoMA is Manhattan itself,” says its architect, Yoshio Taniguchi. “The Sculpture Garden is Central Park, and around it is a city with buildings of various functions and purpose. MoMA is a microcosm of Manhattan.”

It’s always been hard to see the Museum of Modern Art. Neither 53rd nor 54th Street is wide. MoMA has no park to give it contrast, no steps to give it grandeur, and $425 million later, it still has none of those things. What Taniguchi has done, in a renovation of the museum so extensive it amounts to a reinvention, is to have intensified what was already there. There’s a subtle increase in sheen, a blacker black glass than that of the charcoal 1984 Museum Tower, and a whiter white, icier than the original white-marble 1939 façade. His new parts—you have to look closer to see them—make the old make perfect sense. Each gridded façade lines up with the next, like the alignment of the blocks.

At night, when the curators leave the lights on, you can start to see under the skin. The museum seems like a three-dimensional puzzle, a campus crammed and stacked onto not even a single city block. On the second floor, the backlit glass reveals an enormous window into an even more enormous room, with a boxed painting leaning against the wall. People are still working here, as in the lit-up office buildings all around.

“The most apt description of the museum is of a heterotopia, a place made up of many places,” said MoMA director Glenn Lowry last week, a month and a half before the new Museum of Modern Art is set to open. He’s working out of a twelve-by-fifteen windowless office, in a building owned by trustee Jerry Speyer around the corner from MoMA, decorated only by a slightly dreary “Picasso and Portraiture” poster that has been his since the curators decamped to Queens in 2002.

“When we talked to Yoshio about the building, we talked to him about trying to link up in a seamless way these different parts of the museum—the new part, the old part, the parts built in the sixties and the eighties—and to recognize that each part had its own purpose and its own identity within the museum.”

If MoMA has its way, the thousands admitted on November 20 will not see behind the crisp, clean space. They will view the museum’s collection on walls of just the right white, mounted in classically proportioned galleries, each with its own purpose and identity, and all wrapped tautly in a skin of stone and glass. But that skin, like every other aspect of the museum, has been microscopically examined by the museum’s mandarins. At the heart of their debate was one word, represented by the third letter in their famous acronym. Their question is simple:

What Does Modern Mean to the Modern?

“The museum made an effort to create a program of self-psychoanalysis,” says Brian Aamoth, the American-born project director and manager for Taniguchi’s office. “Who are we? Where are we going? And it did two things: It reaffirmed modernism—but they found also that they want to stay with the times.”

“I wanted to provide the visitors with a sense of place,” says Taniguchi, “the experience of viewing MoMA’s collection on their home turf.”

The process began with a retreat at the old Rockefeller estate at Pocantico in October 1996. One participant characterized the event as an “egghead sleepover,” with about 30 curators, architects, and historians debating in a conference room. “Whatever is different about the museum now had its genesis there,” says Terence Riley, chief curator of architecture and design. “One of the high points was when the architects started talking about metaphors. I remember the metaphor of a sponge, meaning a building that wasn’t based on hierarchy because it is isn’t monocellular—it’s a democratic space with an incredible number of points of entry.”

The artist Bill Viola argued that the future of the museum included new forms of art—video art, like his work, but also forms that hadn’t been invented yet. The curators heard him, and the Modern decided to make it a priority to keep mapping the art of the present onto its institutional grid. “Our challenge is precisely the tension that comes from trying to present both the immediate present and the immediate past,” says Lowry. “The moment you render them apart, you’ve lost that tension. What is contemporary today is going to become historical at some point in the not-too-distant future. Then you have the dilemma—where is the line?”

So the museum decided to have it both ways. On the one hand, it had to keep telling the definitive story of Modernism, the movement that began roughly with Cézanne in the 1870s and began to splinter in the 1960s. But it also didn’t want to become a time capsule, a place with, inevitably, less and less relevance to what is happening outside its walls. They decided to make that tension the core of MoMA’s mission. Contemporary art and Modernism would stand against one another, a kingdom fascinatingly divided. Of course, answering that first question led quickly to a series of others.

Should the Modern Move?

“The major question is, Was MoMA right to go through this enormous effort to build on their historical site?” says architect Bernard Tschumi, a finalist in the museum’s expansion competition. “Should MoMA have gone somewhere—say, on the West Side or in Chelsea—and, on a free site, do a building without all the enormous constraints?” MoMA could indeed have moved. This “MoMA Reborn” story might have been written seven years ago as a there-goes-the-neighborhood piece about Columbus Circle. (Briefly, that was a consideration.) We could have had a shiny museum then, instead of a shinier mall.

Since 1939, when MoMA replaced its first permanent home, the Rockefeller townhouse at 11 West 53rd Street, it had expanded as far east (1951), north (1964), and west (1984) as it seemed possible to go. In the meantime, more and more of the collection was in storage, particularly works made and purchased since 1970. Spaces designed for a million visitors a year now served 1.8 million.

One option was to split the museum, circa 1970, and set up a separate museum of contemporary art in a space on the West Side. “We actually got kind of close to thinking we should buy a building over there,” says Riley. Another option was to decamp from 53rd Street and buy a bigger footprint somewhere else in the city.

But to many, the location was just right. “It’s more centrally located than great museums like the Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan,” says chairman emeritus David Rockefeller, who’s been on the board since 1948. “It was put there because my family made available the space, and that was in a sense accidental. But, I think, as it happens, it has worked well.”

When Glenn Lowry arrived as director in 1995, the trustees asked him to evaluate their options. “I said to the trustees, the need for more space is not in and of itself sufficient rationale for expansion. That need was always going to exist. It’s axiomatic that a collecting institution is always going to need more space.” Instead, what he thought the museum needed was a thorough renovation. The historical collection had become static. There was little room for temporary exhibitions, which always came at the expense of the contemporary galleries. “Even if we didn’t add a square foot to our footprint, we needed to seriously address the architecture of our building, and the trigger for going forward was that the Dorset Hotel and some brownstones that belonged to the same family became available,” Lowry says.

After 9/11, the museum decided to phase its construction, so the east wing won’t open until probably 2006, with larger facilities for teaching and study.

2. Ronald S. and Jo Carole Lauder Building

Ronald Lauder made restoring MoMA’s historic architecture a personal crusade. Behind the façades of building by Goodwin and Stone (1939) and Philip Johnson (1964) are the galleries for books and manuscripts, photography, and prints and drawings.

3. The Modern

Danny Meyer has taken over the restaurant (and the lower-priced cafés), which will have its own entrance under the original MoMA’s restored, curved canopy. Diners will get a view of the garden, and food inspired by MoMA’s Bauhaus roots. Opens in January.

4. Museum Tower Cesar Pelli’s 1984 tower, whose residents’ taxes go to fund the museum, now touches down in the restored and expanded Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. His glass-curtain wall also offers a low-key Mondrian quotation.

5. David and Peggy Rockefeller Building

Galleries for (from bottom to top) contemporary art, architecture and design, painting and sculpture, and temporary exhibitions ring a three-story interior court. On the ground floor, an interior street runs between 53rd and 54th, with entrances at both ends.

6. Museum Office Building

In August, the curators moved into this snowy tower and set up in cubicles so stylish they’ve been exhibited at MoMA. A huge elevator runs between the top-floor conservation department and the galleries, so even the largest works can get a cleaning.

The museum bought the Dorset and the brownstones for $50 million in 1996. Rockefeller helped the museum secure $65 million in seed money from the city in 1998 that allowed it to start the fund-raising for what turned into a $425 million project. “A group of us went down to see Giuliani and told him how important we felt the museum was to the city,” says Rockefeller. “I think it was important that the city and state should be participants in a museum that plays such an important role.” And the museum began its $858 million fund-raising process for expansion and endowment, which is still not complete.

“Glenn Lowry said from the beginning that it is going to cost $500 a square foot,” says MoMA head of construction Bill Maloney. “Jerry Speyer, who has built a million office buildings, said it can’t cost that much, but Glenn was right.”

Riley says, “We had to get to that point, and then the point was, Who is the architect to really remake the Modern?”

Remodeling the Modern

“I had a premonition we might win,” says Aamoth, a man not normally given to Delphic vibrations. “Yoshio got a letter from Glenn Lowry asking him only to send in information about the office. He called me into his office and handed me the letter. I didn’t get any farther than the first sentence, when I had the overwhelming premonition that Yoshio was going to do this project. I said, ‘You are going to get this, and I want to run it.’ ”

At the time—this is 1996—Aamoth may have been the only person who thought Taniguchi was going to get the job. After graduating from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Aamoth had traveled to Tokyo to work for Taniguchi, and had been in Japan for six years.

Taniguchi would probably not have been such an unknown if he had designed buildings outside of Japan. Or if his buildings were closer to the capital. Riley reports that trustee Ronald Lauder has joked, “Taniguchi’s museums aren’t hard to find. You fly to Tokyo and you’re halfway there.” Taniguchi is, however, the son of respected postwar architect Yoshiro Taniguchi, also a graduate of Harvard’s GSD, designer of six previous museums. He had the credentials, he had the grace (Riley says, “Once you see his work, you have a hard time seeing a lot of other work and not seeing something missing”), but he was hardly the front-runner. The letter Taniguchi received also went out to some twenty other architects.

Before the letters were sent out, the trustees spent three separate weeks onboard Ron Lauder’s corporate jet, flying first to Europe, then around the U.S., and then to Asia, to look at museums. Riley was the tour guide. “In one day, we crossed the Atlantic, woke up in Bilbao, and went to see the Guggenheim. Then we took off and landed in Arles and saw Sir Norman Foster’s Carré d’Art in Nîmes,” he remembers. “We had lunch there. Then we flew to Berlin that night and landed in Tempelhof airport as the sun was going down, and had dinner with some important cultural figures in Berlin. That went on for five days.”

After the trip, and reviewing portfolios, selection-committee members Sid Bass, Marshall Cogan, Agnes Gund, Ronald Lauder, David Rockefeller, and Jerry Speyer cut the list to ten.

Thinking Inside the Box

Riley had talked Lowry and the trus-tees into having a competition—a public, gossiped-about bake-off—rather than the typical dignified short-list-and-interview process. From the moment the list was released, however, it was clear MoMA was after something different. It had passed over architects of the generation that includes Frank Gehry and Richard Meier in favor of those just behind them. Taniguchi was the oldest at, today, 67.

The ten, who included New York architects Steven Holl, Bernard Tschumi, Rafael Viñoly, and Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, now architects of the American Folk Art Museum next door, as well as then-white-hot Rem Koolhaas, were asked to participate in a three-month charette—an ideas competition—the results of which they had to submit in an eleven-by-seventeen-by-three-inch box. “We said, ‘Anything that you can fit in this box, we’ll accept.’ A lot of the architects cut out the top of the box, and put in little models of their proposals. It was pretty funny,” says Maloney.

The box made sense in another way as well. Acknowledging the tight city site, MoMA had picked a set of architects who play with but don’t break out of the box. No blob-itecture, no titanium frills. The committee members got models: wooden, cardboard, acrylic, metal; they got watercolors; they got collages of the city and collages of circulation. Viñoly came up with an escalator spine, extending the moving staircases Cesar Pelli had installed in 1985 almost the length of the block. Koolhaas collaged a new transportation system, a gallery floor that sunk along a slanted ramp, moving the viewers to the art. Japanese architect Toyo Ito imagined the museum as a “lying skyscraper,” reclining along 54th Street. Their projects were meant to be conceptual, not practical, though when they were exhibited, many just scratched their heads.

Tschumi believed that the museum was pulling in two directions architecturally. “They used the word intimacy, which people since the thirties had used for the relationship between viewer and artwork, a relatively traditional view. But MoMA was also forward-looking enough to mention new types of artwork that we and the curators could not even imagine, and to provide spaces for unimaginable works.”

The trustees cut the list to three: Taniguchi, Tschumi, and Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, then working on the Tate Modern in London. In December 1997, they chose Taniguchi, whose high-Modernist inflections linked with the museum as it was and whose cool elegance and precision held a mirror to the city as it is. “He did very beautiful buildings, very simple modern buildings,” says Rockefeller. “We felt he understood what the Modern was all about. Therefore philosophically we felt he was someone who would work with us.”

“Any of the ten could have gotten it,” says Aamoth. “But I think they recognized that we had solved the problem in an elegant language that said who they were. Why would they want to change their spots at this time? It is called MoMA, after all.”

What’s Behind the White Walls?

Taniguchi, who likes to focus on only one project at a time, thought he would move his operation to New York. But the museum was concerned about the learning curve for an architect building for the first time in New York City and decided to hire the large, experienced firm KPF as executive architects.

Aamoth moved to New York for five years. Eight KPF employees moved to Japan for six months, and a multiyear international tango was begun. KPF architects-in-charge Tom Holzman and Stephen Rustow (who had supervised the construction of I. M. Pei’s Louvre pyramid) flew to and from Tokyo, ten days here, ten days there, for ten months.

“Jerry Speyer had a brand-new, beautiful videoconferencing room,” says Maloney. “So every Thursday night we would have a conference call. It would be his Friday morning. We would have 20 to 25 people in there to talk about what we would do with the curtain wall or just any issues that would come up.”

Taniguchi works first in model, building pieces of staircases and sections of the city. “By the middle of schematics, we had a ten-foot model of the project, and there were also three separate models of the entire project and all of 53rd Street, 54th Street, and Sixth Avenue at a quarter-scale,” says Rustow.

“Taniguchi said, ‘If you raise really a lot of money, I will make the architecture disappear,’ ” says Paola Antonelli.

Rustow and Greg Clement, KPF’s managing principal, were also tour guides, of sorts, for Taniguchi. “Yoshio asked us to inculcate him into the building culture of New York,” Clement says. “I remember trying to figure out where we could take Yoshio that would have the level of sophistication and execution he is accustomed to.” So where did they take him? There’s a long pause. Then Rustow says, “One of the most interesting buildings to look at—because it had just been completed and because, as it later happened, the construction manager who was responsible for the work there was responsible for MoMA as well—was the Rose Center,” the globular astronomy addition to the Museum of Natural History. The architects were impressed with the way the panels on the sphere fit together seamlessly, but were less impressed with some of the workmanship: how the plasterwork met the metal, how tight you could expect joints to be, and—something that drives every architect nuts—the metal handrails. “And they are one of most important details,” Clement says, “because they are the most tactile; you’re touching the handrail and pushing the door.”

Production values of the new MoMA—aluminum door frames, double-square doorways, radically minimized air-conditioning ducts, and, yes, handrails—have already thrilled design connoisseurs who’ve toured the building. Taniguchi’s perfectionism reaches its apogee in the exterior, where he wanted the large surfaces of granite and glass to read as perfect planes. He demanded the bare minimum of clearance, three-sixteenths of an inch, between each panel. He feared that as the floors deformed when the galleries were full of visitors, the walls would also sag; the curtain-wall consultants came up with a way to free the façade structure from that of the floor levels.

The flip side of radical understatement is the divinely dull. Taniguchi may have solved the problem of the museum’s urban site so well that he’s written himself out. “Taniguchi once told Terry, ‘If you raise a lot of money, I will give you great, great architecture. But if you raise really a lot of money, I will make the architecture disappear,’ ” says Paola Antonelli, MoMA’s curator of architecture and design. “It is so Minimalist, it is baroque.”

And, Oh Yes: What Should Go on the Walls?

When moma was born in the late 1920s, its mission was straightforward. “Right from the beginning,” says David Rockefeller, “the founders, including my mother, felt it needed to come into being in order to accommodate some of the work of contemporary living artists.” Rockefeller remembers his mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, meeting with Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan to discuss this museum for contemporary artists in their townhouse at 10 West 54th Street. But as Modernism, the great art-historical current that sustained the museum, has gradually dissipated, the museum’s mission has become divided. “It has the historical responsibility of the modern movement and then, in a more contemporary sense, of trying to identify the best living artists of today as our curators see them.”

John Elderfield, head curator of painting and sculpture, is the one saddled with the task of pursuing the modern and the contemporary at once. “To see contemporary art in a museum which has Picasso and Brancusi is just great for contemporary art,” he says. “In a way, it shows what the expected level of achievement should be. To see Rachel Whiteread in the same building as Brancusi actually informs Brancusi.” But the way the museum is going to show them is very different.

Painting and sculpture from 1880 to 1970 take up two floors at the new museum, as at the old. The collection starts on the fifth floor, just under the temporary-exhibitions gallery, and spirals down and forward in time. “Each of the galleries has a demonstrable subject that is limited in the number of years it covers,” Elderfield says. “My sense of the success of these units is if one could imagine any one of them being moved out somewhere else—my mental image is always the middle of Central Park. Would people think this is cogent and makes sense? ‘There’s a new Surrealist pavilion in Central Park.’ ”

Visitors will be greeted on the fifth floor by Rockefeller’s Paul Signac portrait of Félix Fénéon, collector, critic, dealer. The painting, on loan for four months, brilliantly represents the nexus of art and money that is the basis of the modern and the Modern. The first gallery will also hold works by Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh. Then visitors will have a choice—and this choice is a crucial part of the museum’s new exhibition philosophy—to go right into Cubism and Picasso, or straight on into Expressionism, color, and Matisse. “The advantage of this isn’t only that people feel more comfortable if they have a choice, but I think it is actually truer to what modern art is,” Elderfield says. “It isn’t one development. It’s a sequence. It’s a debate between different opinions about what modern art is, as represented by these movements.”

“There was general agreement among curators in the museum that the installation of the collection that had existed for twenty-odd years was too linear and was too much of a marathon. It was thought that it should be more open in terms of where you came in, where you got out, so that not everything fit into one grand unfolding narrative,” says Robert Storr, former senior curator of painting and sculpture and a professor at the Institute of Fine Arts. “And it had to be more integrated in terms of different mediums and different modernisms.” At Pocantico in 1996, Kirk Varnedoe, at the time the curator of painting and sculpture, had suggested dispensing with a physical-historical sequence entirely, offering it via audio guide, and letting each gallery be an episode.

Floor five will take you from Cézanne through the early forties. Floor four will pick up with early Abstract Expressionism and the School of Paris and wrap up with Eva Hesse and post-Minimalism. “In the old museum, the collection really stopped in the sixties, and even in the sixties, there wasn’t much space devoted to it. There were two small rooms just before the stairway,” Elderfield says. In the new museum, the fifties and sixties get half a floor, and from certain spots, you can make the same sort of choice as that between Picasso and Matisse: Pollock or Newman?

Some of the departmental galleries are growing minimally, which has caused some grumbling. “Based on what Kirk Varnedoe told me, there will be somewhat less space for the permanent collection before 1960 than in the old building, though the space for post-sixties art will be vastly expanded,” says Storr. Department heads say their galleries feel better—higher ceilings, fewer walls—allowing for more flexible exhibitions.

The museum has also been buying strategically, and some of its major new pieces will end up in these fourth-floor galleries. Jasper Johns’s Diver; a 1950 Picasso sculpture of a pregnant woman, rarely seen before; and a couple of key Minimalist purchases that Elderfield won’t name—one a late work by a star, the other a work from the dawn of the movement. Elderfield is wary of saying too much, explaining that while he’s prepared for the calls of aggrieved living artists after November 20, he doesn’t want to take such calls now.

How Shocking Is the New?

By recommitting to contemporary art, MoMA is undoubtedly making its life difficult. Yes, there may be masterpieces, but there are infinitely more mistakes and detours and dead ends. For the museum’s founders, that was part of the excitement. Founding director Alfred Barr brought the latest work from Europe to New York for the museum’s early shows, like “Cubism and Abstract Art” in 1936, and showed it in the latest manner: just one or two pieces on seagrass-covered walls, the items isolated for appropriate thoughtful contemplation. The museum owned none of the works—its permanent collection wasn’t created until the sixties—and the three founding ladies planned to maintain the museum as an ad hoc, always-moving-forward enterprise. “If that had been maintained, our collection would start with Jasper Johns,” says Elderfield, referring to one of the eldest of contemporary artists. “As the museum evolved, there wasn’t something called ‘modern art’ and something called ‘contemporary art’ but the thought that contemporary art was the most recent version of modern art.”

The new galleries represent “a debate between different opinions about what modern art is,” says curator John Elderfield.

Up to the sixties, the museum maintained its currency and helped to assert the primacy of New York as the new center of Modernism, through curator Dorothy Miller’s numbered “Americans” shows. From the perspective of today, the lists of artists she chose (“Sixteen Americans” in 1959, often pointed to as a high point for prescience and tastemaking, included Frank Stella, just out of Princeton, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns)—are a fascinating collection of stars, even supernovas, and artists lost to history.

The new MoMA is reinforcing that original commitment even as its position as chief custodian of twentieth-century art has made it more protective of its curatorial judgment. It’s that duality that is liable to cause continuing institutional neurosis.

Many of the works given pride of place are already canonical. The first piece of art you will see in the museum is Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk, a work from 1969, the hinge between modern and contemporary, centered in Taniguchi’s vertical court. Exit that court, and you’ll be tossed into a realm of big Serras, big Twomblys, sprinkled with potential household names of the future.

In the second-floor contemporary-art galleries, curator Ann Temkin is installing work of the past 30 years, with areas for the seventies, eighties, nineties, the paintings and sculpture mixed with selections from design, photography, prints. “The installation there will rotate more quickly and will always be treated more like a gallery space than a museum space,” says Elderfield, “without any pretense that this is telling the definitive history.”

The museum has continued to collect artists who made their names in the sixties through the present, so some may appear both upstairs and downstairs. The museum purchased a late Francis Bacon triptych during its Queens hiatus. Collected in the seventies were Pop, Minimal, process, and installation art by such artists as Acconci, Beuys, Burden, Fabro, Kelly, Merz, Richter, Rosenquist, Serra, and Turrell. From the eighties, Lowry mentions Bruce Nauman and Jeff Koons. And from today, the museum has collected sculptor Whiteread and photographer Jeff Wall, along with three artists seen in this year’s Whitney Biennial, painters Julie Mehretu and Elizabeth Peyton, and video artist Eve Sussman. The museum tends to favor artists who refer to the history of art—it reinforces their definition of the modern as continuous—so Sussman’s video piece refers to Velázquez’s Las Meniñas. Mehretu’s huge canvases manipulate the visual language of architecture into Abstract Expressionism. Peyton paints portraits.

The museum has bought actively with the new galleries in mind. In 2004, a set of trustees endowed the Fund for the 21st Century with $1 million to purchase works made within the past five years, says drawing curator Gary Garrels, “for generally less than $50,000. It could be a $5,000 drawing or a $3,000 photograph.”

Safe choices are as liable to create controversy as bold ones. The museum, for instance, just purchased Gordon Matta-Clark’s Bingo. “Why are they buying Gordon Matta-Clark twenty years late?” asks Romy Golan, a professor at the cuny Graduate Center. “It’s all late, late, late. They are becoming like the Getty.” Another historian suggested that the emphasis, in early press, on the museum’s ability to show a multiton Richard Serra indicated similarly out-of-date priorities—like Matta-Clark, he’s already in the canon.

Golan believes MoMA, which she loves, has abandoned its taste-making role by abandoning thematic shows after the disastrous “High and Low” of 1990 and by focusing on its own single-artist retrospectives. “If they have a brief, that should be to rewrite the history of the last 30 years. They can do work on contemporary art, but it doesn’t have to be from the last five minutes.”

“Artists are usually most interesting in mid-career, in their forties, fifties,” says David Zwirner, of the eponymous gallery, who sold the Matta-Clark to the museum. “MoMA has traditionally done the late-career retrospective, like Richter. I am hoping for more of a focus on artists in the middle of their careers.”

Many believe the museum’s smartest move was to buy the Swingline stapler factory in Sunnyside. It is to the boroughs that the younger generations are going to make and sell art; MoMA and P.S. 1 are planning a second Greater New York show for 2005. “The center of gravity in the art world is shifting east,” says design and bookstore architect Richard Gluckman, whose first job in New York, 27 years ago, was working with Dan Flavin. “This next generation, a lot of it’s going to come out of Brooklyn and Queens.”

Is There Life Beyond Art?

As construction got under way in 2001, the museum began to think about other design projects that might fit within Taniguchi’s new walls. The museum’s logo got freshened. Canadian megadesigner Bruce Mau came in to consult about the museum’s new signage, while hip title designers Imaginary Forces were asked to invent a new interface for the monitors that will provide information to patrons in the lobby.

And Lowry and Riley cooked up another set of short lists, one for a restaurateur for the museum’s restaurant and cafeteria, the other for the architect who would revamp the museum’s bookstore. “It is in keeping with Taniguchi’s original concept of the building as an urban plan,” says Riley. “It’s almost like a small portion of a city, where, of course, there are different architects doing their thing.”

Danny Meyer, who’s running the museum’s new restaurant, The Modern, certainly believes that his involvement was fate. “The idea to do this actually came to me from the late Paul Gottleib,” he says. “Paul was a trustee for many, many years at MoMA. One day, he came to me and said, ‘You must, I repeat, you must get your name in the running for this restaurant.’ ”

The restaurant’s furniture, place settings, and ornaments will, as in the rest of the museum, be dominated by Danish design, with benches by Poul Kjaerholm (who seems to be the new Eames), mixed with some by Florence Knoll for weary gallerygoers.

The final curated aspect was the food. Meyer remembered his parents’ MoMA calendars featuring Josef Albers. “I think of the Bauhaus movement, which makes me think of the eastern part of Western Europe and Bayer and Albers,” he says. He chose Gabriel Kreuther, from Alsace, to be the chef.

Richard Gluckman, of Gluckman Mayner Architects, designer of the Dia:Chelsea and Helmut Lang store in Soho, took Taniguchi’s design as his jumping-off point, re-creating his palette in a dizzying variety of materials, with graphics by cutting-edge Dutch designer Paul Mijksenaar. The 6,000-square-foot retail store is under the new roof, paralleling Taniguchi’s block-long lobby and creating an indoor retail street. Gluckman is best known for his creation of Chelsea’s gallery style with the renovation of industrial spaces into the Dia and Larry Gagosian and Paula Cooper galleries. He continues to have a close relationship with artists, which makes him a perfect go-between for the curated shop and the curated gallery. When I asked him whether working for MoMA, where every item in the store is subject to curatorial review, was different from his other shopping designs, he laughed. “When we started doing retail, we started at the top with Versace and Helmut Lang. These clients were fairly intense about their own curatorial imperative, so that’s one thing that’s consistent.”What’s MoMA Now?

“Collectors of art who believed in art not as an entertainment enterprise, and not as a business, but as a truly important kind of thing began to feel like dinosaurs after Bilbao,” says Terry Riley. “What people will see here is this unexpected thing, that a museum can be a great place for art and also be unbelievably dynamic and spectacular. This ran contrary to the accepted wisdom in the art world, which was that you either had a building that was a work of art unto itself or you had a nothing, neutral piece of architecture. I think what Taniguchi’s building does is blow that up a little bit and say ‘Sorry, those aren’t the only two choices.’ ”

I am standing in what will be the Museum of Modern Art’s new Architecture and Design galleries, trying to get a sense of what the eight-year process accomplished. In the old Modern, the views were all north. In the new Modern, you can see north and east through floor-to-ceiling glass. South, too, through heavily darkened view panels in some of the galleries. Manhattan is never far away. “I wanted to provide the visitors with a sense of place—the experience of viewing MoMA’s collection on their home turf,” Taniguchi says.

On 53rd Street, Taniguchi had to contend with the ghosts of MoMAs past. I think part of what won him the competition was a graceful sketch of all the 53rd Street façades reduced to their gridlike essences, with his addition (hopefully labeled “1999”) tucked in between 1984 and something extra for 2010. Another sketch, labeled “the diversity and abundance of what has been accumulated,” added the profile of St. Thomas to the mix, so that its carillon can be read as a miniature museum tower, and the rest of the buildings like a consistent roofline of rowhouses.

The sketches showed that Taniguchi understood exactly what he was getting into—Manhattan, in all its complexity—and how to make his building make sense of all the others—a Utopian view of a heterotopian situation. Another way of saying this is that the new MoMA is a question, sublimely unanswered.

The Making of the MoMA

A Gallery of New Acquisitions