The clock is striking midnight at Rockefeller Center. On Central Park West, Conan O’Brien’s 2-year-old daughter and his wife, pregnant with a boy, are fast asleep. O’Brien, 42, is dressed in an NBC security guard’s uniform with an extra-large hat on his extra-large head, stalking the hallways trailed by two cameramen. “He’s wide, I’m tight,” one reminds him. “Figured that,” says O’Brien with a lightning-fast smile, there for the second something is funny and otherwise hard to find.

The hours-long night of videotaping, during which O’Brien, strangely, remains in character as the Red Fox, has already included a search for the ghost of Al Roker and the robot soul of Stone Phillips, a shriek of “Defcon Level Nine, we’ve just seen a giant squid! Avast, avast!” and the demand that a bystander hand over his camera: “This is New York City,” scolds O’Brien. “Never give someone your camera.” He tells a half-dozen tourists to squat on the neutral-colored tile of the Rock Center lobby checkerboard with their hands over their heads while chanting “Whee, I’m a top,” and asks, “What is wrong with you people? Have you no dignity?” Then he pushes open the revolving door of the midtown Art Deco masterpiece where television was born and enters the humid city night.

A glimmering blonde rolls down the window of her BMW and yells, “I love you, Conan!”

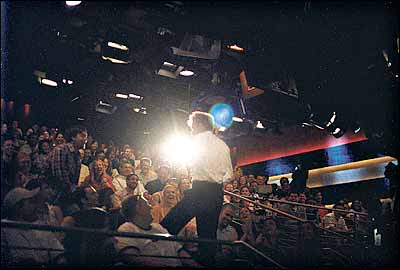

In the blink of an eye, a gape-mouthed mob of 50 forms behind O’Brien as he dashes to and fro on 49th Street—a visible show of the raw power of the late-night talk-show host, a job in which everything that happens in a whole hour of television is thought to be an extension of you and in your complete control. Frisky, he jumps onto a pedicab for a few pedal-strokes, flags down a horse-and-buggy, then climbs onto a passing city bus, its doors wheezing open in the middle of the block—“Bus looks good,” he pronounces from the top of its stairs. On the street, he points into the crowd: “Virginia, I want you home in five minutes!” he tells one woman. “But I’m from Turkey,” she says.

The mob waits expectantly for the next antic. “Please disperse!” says O’Brien. “There’s nothing for you to see here. Return immediately to your loved ones.”

Then O’Brien pulls out one of his signature shticks.

“My show,” he says, with something in between a laugh and a sneer, “is on way too late for any of you to care.”

O’Brien, who is optimistic and fatalistic in maddeningly equal proportions and provides few clues to which way he will swing at any given moment, has been buoyed and in some ways consoled by this 12:30 a.m. fail-safe for the past thirteen years: Late Night With Conan O’Brien is on too late, no one is watching, the show is not a monument in popular culture. O’Brien’s show has consistently drawn an average of 2.5 million viewers per night for the past nine years, and unlike Letterman’s (4.5 million) or Leno’s (5.6 million), the numbers rarely change according to the strength of A-list guests or the quality of 10 p.m. network drama and local news. He has expanded on Letterman-pioneered meta-show devices in which the camera becomes a prop—O’Brien is perhaps the only talk-show host to lick the camera—and added to this a Pee-wee’s Playhouse–on–crack sensibility where O’Brien, as the world’s tallest leprechaun, presides over and participates in oddball sketches that keep the fourth wall intact (e.g., O’Brien as the Red Fox). This is part of what New York excels at these days, smart sketch comedy as seen on Saturday Night Live or at the Upright Citizens Brigade. It is perhaps also part of what has given New York a bad name in comedy in the rest of the nation, which ranked the East Coast the least-funny region of the U.S. in an August poll by the Kaplan Thaler Group (the South came in first).

“Have these people been to Salt Lake City recently? Have them go to Salt Lake City and order a lobster and see how funny that is,” says O’Brien. “New York is a social experiment—the results aren’t in yet, it may not have worked, they took way too many people with a large disparity of wealth, stacked them on top of each other, and sprinkled bagels over the whole thing. Contrast breeds comedy, and the more extreme the contrast, the better the comedy.”

The wit and wisdom of Conan O’Brien: “The federal government asked people not to return to New Orleans because it’s still not safe. Then the federal government said the same thing to the people of Detroit, Cleveland, and Newark.”

In four years, O’Brien will no longer enjoy the pathology of 12:30—“Do you love me? Well, I don’t care if you don’t, because I’m on at 12:30.” In one of the great anticlimaxes in recent late-show history, certainly as compared with the epic saga of the Mike Ovitz–negotiating, Warren Littlefield–bumbling, and Jay Leno–closet–eavesdropping of the Leno-Letterman tussle over the Tonight Show chair in the early nineties, it was announced one year ago that O’Brien would succeed Leno in 2009. With about a year left on his contract, O’Brien was receiving overtures from ABC, and signaled in the press that he was ready to move on. After that, NBC moved quickly. (O’Brien had previously ignored feelers from CBS when Letterman’s contract was renegotiated in 2002, and turned down a reported $25 million offer from Fox at the same time.)

O’Brien made his decision without waiting for what will most probably be a search for David Letterman’s replacement around the same time Leno steps down. And Jon Stewart is the most obvious candidate for that seat. By the way, if you want to get on O’Brien’s good side, do not bring up Jon Stewart (who failed at his own late-night show in 1994), as it makes him bristle at the unfairness of Stewart’s comedic hegemony—he won two Emmys last week—for a far less complex, toilsome, and popular show, at 1.4 million viewers per night. Stewart’s contract is up in 2008 (though Viacom could conceivably move him from Comedy Central to CBS whenever the need arose), setting the stage for a potentially sensational grudge match.

Leno may have torn down the Church of Johnny, but there’s still a pulpit. Middle America is comfortable with Leno, who, gray though he’s going, still seems like a big, cheerful kid from the suburbs, a man who knows his place in the firmament. And he does. “For everything about how incredibly important the job is, there’s something else about how incredibly trivial it is, and the truth is somewhere in the middle,” says Leno. “You believe all that you can. I’d believe it all if I could.”

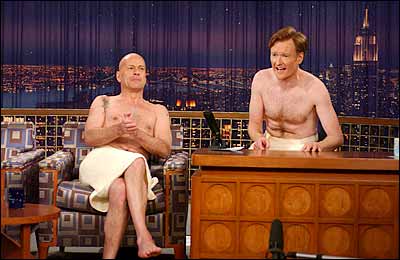

The facts are that O’Brien will inherit the longest-running entertainment program on television, one of the remaining network television profit areas, and what was once and may still be the most important job in comedy (in ’92, 50 million people watched Carson’s final broadcast after 30 years on the air). Whether that role will continue to exist in American culture is up to O’Brien, accidental hero, an unknown writer for Saturday Night Live and The Simpsons chosen to replace Letterman by NBC demigod Lorne Michaels. O’Brien’s a TV Dadaist, an envelope-pusher, a weirdo, with jokes that veer from the non sequitur to the borderline pornographic. From a recent monologue: “Actor Johnny Depp says he wants to shake up his onscreen image, so he’s thinking about starring in a hard-core-porn film. The porno is going to be called Charlie Takes It in the Chocolate Factory.”

O’Brien’s four-year waiting period is a bit of a show-business absurdity—but he may need that much time to get the chocolate-factory jokes out of his system and work his way toward a less ridiculous haircut. Whether he’ll ever get there is a serious question in the television world. There’s something oddly unprofessional and ad hoc—an imaginary giant squid, for example—to O’Brien’s show. He’s as much of a nervous Nellie as Jack Paar, but he draws our attention to it, constantly poking fun at himself. It’s part of his charm at 12:35—but will it play at 11:35?

“Mary-Kate Olsen is thinking of dropping out of college. When asked why, she said, ‘Because I have a billion dollars.’ ”

Conan himself says he hasn’t thought much about how he will format his Tonight Show. “The Tonight Show should become a lot more like The Price Is Right,” he says. “It should be more in the game-show area, because if you’re not giving away a boat, no one is taking you seriously. Also, it should be broadcast from a different city every night. Remember ‘Where in the world is Matt Lauer?’ It should have that kind of quality. If you can figure out we’re in Omaha tonight, you get the boat. Also, I want to bring smoking back. These are the kinds of things I’m thinking of.” And here it comes, the special O’Brien dash of self-deprecation, perhaps less the product of insecurity than a cry for attention by the consummate middle child: “This is why NBC will never give it to me.” But you have the job, Conan. “It’s three years—that’s a long time.” Whatever. “Something could happen,” he says hopefully. “I could go crazy.”

Have you seen O’Brien around town? You would remember. At six-four and 177 pounds, he is very, very tall, and very, very thin, his intelligent, earnest face a kind of looming moon scored with knife-thin creases that fill in with heavy show makeup, leaving a muddy ring on the collar of every dress shirt he owns. He is the most naturally gracious fellow you could hope to meet, though his main hobby is biking on his titanium-carbon Serrotta around the park drive at top speed, because that way he can be with the people, but they not with him. Otherwise, he’s bombarded by calls of “Hello, Conan” (he welcomes each with a nickname, like “Hello, Chopper”) followed by the inevitable “You are sooo tall!” He always says the same thing: “Gotta get a bigger TV.” O’Brien says, “It’s not that good a line, but it kills every time. It drives my wife crazy. I’m like, ‘You want a new line for everybody?’ ”

O’Brien and Liza Powel met when she consulted on the show as an advertising professional, and they married after dating for two years—“She had the tiniest apartment on 105th Street. I thought, ‘I don’t have emotional feelings for you at all, but I feel a responsibility to get you out of this apartment.’ ” Theirs is a quiet life—a house in Connecticut, a golden retriever, a Ford Taurus. He watches TV, like I’m Alan Partridge on the BBC and MTV’s Laguna Beach (“At first I was trying to make fun of it, but then I was like, ‘Kristin is a bitch, but she’s so much more interesting than L.C.!’ ”). He and his wife take their daughter to the zoo: “At the Bronx Zoo, the animals have space, so they run and hide. It’s bullshit. In Central Park, they’re there like the rest of us, sitting in condos and flipping through magazines.”

“After sleeping with his nanny, Jude Law said, ‘I really have been in everything this year.’ ”

O’Brien doesn’t go out much, anyway. “There is this expectation that because I live in New York and broadcast out of Rockefeller Center, at night I should have a few Scotches at some cool bar, then it’s downtown for experimental theater and off to the club for saxophone, home at four in the morning for a little cocaine and off to sleep,” says O’Brien. “You know, a little bisexual relationship—‘I have my wife, but I also see Scott.’ ” Instead, he’s home after work or at least after dinner (O’Brien doesn’t watch the show at airtime, because it revs him up too much to fall asleep). “I walk the halls like Nixon with the portraits in his last days, talking to photographs,” he says. “There is nowhere to put the energy.”

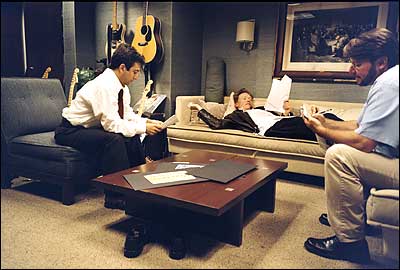

Even if he didn’t have to be funny on television for an hour a night 168 times a year, O’Brien would have an enormous amount of energy. Conversation with him never stops. When the engine sputters out, he rambles. (The serious answer about his plans for the Tonight Show: “All I know is that I’m going to really think about it, and do a funny show, and it’s going to be an extension of who I am and what I’ve achieved over many years, and probably at that point will have morphed into something a little different, and whatever it is, I will do everything I can to make it good and the chips will fall where they may.”) All day long, he’s yammering away at the show’s studios as he dashes through his daily schedule: postmortems with essential staff and a writers’ meeting after the show, another writers’ meeting in the morning, perusal of monologue jokes at two, rehearsal at 2:30, makeup at four, coffee at 4:45, a run-through of the “mono” at five, audience warmup at 5:15, and—sis-boom-bah—time for the show at 5:30, the same taping time as Carson’s.

As a kid in Brookline, Massachusetts, O’Brien took tap lessons from a protégé of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and he does a little soft-shoe in the hold before he goes onstage. He crosses himself too, every time.

One of the problems of a nightly talk show is that everyone has too much to do at different times of the day, and when someone doesn’t have anything to do, he likes to distract the other people. It is 11 a.m. and Mike Sweeney, O’Brien’s head writer and quite possibly the nicest man in New York, is trying to come up with a short skit to fill two suddenly empty minutes after the monologue, and O’Brien is shooting the breeze. He expends little effort editing writers’ monologue jokes, but he could talk about show characters and cartoons all day long—the Masturbating Bear, Embryonic Rockabilly Polka-Dotted Fighter Pilots, Robert Smigel’s Triumph the Insult Comic Dog (the puppet who says all the hostile things to celebrities O’Brien cannot, because he is constitutionally incapable of offending a stranger to his face). Later, the NBC censors will prevent him from airing Chewbacca Stuck in a Glory Hole, and O’Brien won’t like that one bit. “Guys,” groans Sweeney, “We need a top of one!”

The writers, as motley a crew as you would expect, but all of them remarkably upbeat, nonconfrontational, and possessed of an innocence that makes one wonder if they listened to what people said about them in junior high, wander in and out of Sweeney’s square, gray, not particularly clean office. (The stains on the floor, Sweeney explains, are from fondue. “ ‘People, use pots,’ I tell them.”) The writers are comfortable around Conan, but just. He accepts their ideas, sometimes with glee, but rarely gets excited by early notions. One time, I walked in on him beating one with a rolled-up Daily News.

“What if Conan gets a call from his conscience?”

“That’s great,” says Sweeney. “Let’s not do it.”

They muse and brood.

“You know, there’s an inverse proportion to how much studios spend on the opening weekend and how good the movie is,” drones basso-voiced writer Brian McCann, munching a handful of pistachios.

“McCann’s new character is a guy who knows a ton about the industry and loves pistachios,” says O’Brien.

“When me nuts go away, so does me knowledge,” says McCann.

Look at these guys (and they are guys; there’s not one woman out of ten sketch and four monologue writers): Sweeney is massaging a bowling ball, another is twisting a piece of bent metal, the one after tearing apart a Styrofoam bowl, the next playing with the ribs of a broken skeleton. A half-size Chris Farley recently hired from The Onion is shaking his knees like it’s below-freezing while listening to his iPod. I guess he’s paying attention—he was the big winner at a meeting yesterday: For a skit about minor-league-baseball mascots, he came up with the character of Mayor McCheese with Tourette’s syndrome. Are these O’Brien’s peers, even if they are unable to banter onscreen with Rachel McAdams or cut a figure at cocktail parties with Jeff Zucker?

O’Brien talks about how much he’s always wanted to do a bit on the contractor for Hitler’s bunker—“Everyone’s coming into Berlin, and he’s saying, ‘You really don’t want to rush this kind of work, you want to do it once and be glad you have it.’ ” McCann talks about a new waterfall discovered by a 93-year-old in California. O’Brien talks about an Irish guy who discovered a beautiful cave but kept it a secret, and relates that to the great resentment of the Irish people (“I discovered a natural wonder! Shh—that’s nobody’s business! Get inside and resent it! Resent what? Just resent it!”). There is for some reason a gigantic amount of giggling over the idea of Sean Connery Air—no food, no blankets, and you’ll like it that way.

“According to the latest polls, President Bush’s approval ratings are at an all-time low. In response, President Bush said, ‘Yeah, but my disapproval ratings are at an all-time high.’ ”

“What have we accomplished here?” muses Sweeney. “Absolutely nothing.”

O’Brien wishes he could hang out with the other late-night hosts, but no one makes an effort. He’s had a few conversations with Letterman, and has visited Leno a couple of times. (“He picked me up from the Beverly Hills Hotel in a car from 1918 that had gas lanterns and looked like it ran on peat moss,” says O’Brien. “Yah, Conan’s not a car guy,” says Leno. “I think he was confused and frightened by the whole experience.”) There was a phone call between Carson and O’Brien after his appointment was announced. “It wasn’t a long conversation, but he kidded me: ‘It sure is a long engagement before the wedding,’ he said. The tone was that I was getting an old Packard,” says O’Brien, “and he was the original owner telling me, ‘Isn’t it a great ride, that car? Doesn’t it have a smooth shift between third and fourth?’ I told him I’d try not to screw up the franchise. ‘Ooh, that is some franchise anyway,’ he said.” Says Bill Zehme, author of the upcoming biography Carson the Magnificent, “Johnny lost pride of ownership when he left Burbank. In later years, he watched reality shows and loved to mock bad television—that was much more his interest than tuning into the late-night boys.” A few months before Carson died last January, a TV program asked him what he would be doing the day O’Brien took over: He said he thought he had a colonoscopy scheduled for that day.

O’Brien describes his initial vision for Late Night as a mix of Carson’s classic sixties charm—sidekick, orchestra and bandleader, suits and ties—and Letterman’s smirking send-up of the talk-show form. It didn’t work so well at the beginning: His first year ended with NBC’s offering him a thirteen-week contract, with interns filling empty seats in the audience, and with his being instructed by the Washington Post’s Tom Shales to “return to Conan O’Blivion whence he came,” all the while weathering the encroaching threat of Greg Kinnear at 1:30 a.m. and executives calling for sidekick Andy Richter’s head (one exec told O’Brien to “get rid of that big fat dildo”). “Most people find their voice when they’re trying to be somebody else—musicians start out idolizing another musician, and it’s their failure to be that person that makes them worth listening to,” says O’Brien. “Over time, who I was came out. I’m from a large Irish-Catholic family, I have my own particularities, I’m screwed up in my own way, so naturally it’s going to be different.”

The problem is that even though he is able to preserve a modicum of cool in person, there is nothing about O’Brien onscreen that is suave. Nor is there that hostility under the surface that used to make Letterman so exciting. O’Brien is first a wonk and second a goofball—a smart guy who watched too much TV as a kid and takes an almost academic interest in turning the television-comedy paradigms on their head. “Don’t get me wrong, a really good joke is great—it’s a nugget, an element in nature, it shows up on an electron microscope,” says O’Brien. “I love it when I have good jokes. But what I really love to do is play with them.”

The third of six kids—his father is a microbiologist and his mother a retired lawyer, and despite such professions, they are apparently very funny—O’Brien discovered late-night television at 10, when his dad, who never missed a night of Johnny, let him stay up for the monologue on Friday nights. “I was interested in this guy who made my dad laugh,” says O’Brien. “I remember watching Carson the day after Don Rickles hosted for a week. He noticed his pencil box was broken. McMahon said it was broken when Rickles was there. Carson walked off the set to where Rickles was filming C.P.O. Sharkey. I think my eyes melted: ‘He can walk off one show and go onto another show?!’ ” Shortly thereafter, “I was one of these kids who really paid attention to what was happening on TV—‘Alan Thicke is going to have a show? Let me check it out and see if it’s going to be any good.’ ”

“Apparently, there’s a new Paris Hilton sex video. Hilton said, ‘I feel the first one left a lot of unanswered questions.’ ”

O’Brien’s other comedic touchstones are Saturday-morning Warner Bros. cartoons (he loved the coyote and how all those jokes had to work silently); an SCTV skit in which John Candy, as Yellowbelly, a cavalry officer kicked out of the Army for cowardice, shoots a mother and child for saying his name; the Eiffel Tower–is–in–D.C. episode of Green Acres; the Batman episode where the villain Shame insults Batman with the line, “Your mother wore Army boots,” and Batman responds, “Yes, she did, and she found them quite comfortable.”

“Anything ridiculous and apropos of nothing, I responded to,” says O’Brien. He was 16 and leaving for school when his sister called him back inside the house to see David Letterman on his morning show. “He had a photo of a dog behind him and a gap in his teeth and he looked completely strange,” says O’Brien. “At that moment I realized things were going to be different.”

As a college sophomore, O’Brien made a pilgrimage to Rockefeller Center to see Letterman. Now he works in the same studio and wishes he could stay. But Rock Center forever may turn out to be a pipe dream for O’Brien—Letterman, whose contract is up in 2007, might end up staying longer than Leno, just to win the last battle of the late-night war. If Letterman’s still kicking around, O’Brien will most certainly need to take his show to Burbank (NBC moved Last Call With Carson Daly, the show that follows O’Brien’s, to Burbank this summer). “Well, there’s a lot of television history in Burbank,” says O’Brien, over dinner at Lattanzi, an Italian Jewish joint in midtown apparently popular with the ranks of the comedy elite—Lorne Michaels is in the back “Lorne’s Here Room” with new Saturday Night Live cast members, and everybody meets awkwardly on the stairs of the restaurant. The new kids tell O’Brien they love the way he reinvented late night. “Why did you say that with a question mark?” drones O’Brien.

He settles in his seat. “I’m open to going to L.A.,” he says. “Mostly because it won’t be my choice.”

In many ways, O’Brien is unscarred by his celebrity. I asked him if he enjoyed himself at the Emmys two weeks ago: “I like the presenting, but I don’t like the sitting,” he says. “I really liked hanging out with Will Arnett and Sacha Baron Cohen—being with people like that is why I got into this business. Will and I walked into the Governor’s Ball, and we were just acting like asses. I kept explaining to him that a lot of people were going to be asking me for my autograph, and he was saying, ‘That’s terrific, Conan. I’m going to use this candlestick to rip my throat open now.’ It was stuff you’d be doing to amuse your friends if you were 8. I love that.”

“Donald Trump said if he were president, he would’ve caught Osama a long time ago. Then somebody explained to him that Osama and Omarosa are not the same person.”

He’s a Harvard boy, and not everyone likes those. O’Brien, two-time editor of the Harvard Lampoon, an honor shared with Robert Benchley in 1912, doesn’t make fun of himself all the time. He spends an enormous amount of time explicating jokes, and there is nothing funny about that. (He should perhaps heed Michaels’s advice: “I don’t want to get into any theoretical ideas about comedy,” Michaels says to me. “Anybody who talks about comedy for more than two minutes is not funny.”)

O’Brien does have some sharp edges, mostly stemming from his differentiation between dumb people and smart people—he sneers at the writers from time to time and calls out to his assistant in a tone of voice that gave me chills (he makes free use of a button he can press on his desk to slam his door shut, too). Oh, the villainy! And he goes on and on about his own work ethic and has little respect for guests he deems not worthy of his show—his highest praise is calling them “likable.”

“Some guests get on the phone with the bookers and they’re like, ‘Oh, I like to wing it.’ ‘Well, I heard you recently bought a cow.’ ‘No, I didn’t.’ ‘What do you like to do for fun?’ ‘I like shopping. Listen, I gotta get out of the car now.’ Then you have Schwarzenegger calling four times in the three weeks before he comes on—‘Do you have more stuff for me? Did you punch it up?’ ” O’Brien carries the show, and he knows it. “We’ll have someone who is famously not a great guest on, and in the morning my doorman will be like, ‘Oh, wasn’t so-and-so funny?’ ” says O’Brien. “I’ll be like, ‘I did that. That was me!’ ”

Backstage at Late Night: Rob Schneider’s telling a lesser-known but older comedian, “It’s all about being yourself—keep going with that”; slender and stylish Kate Hudson’s striding down the hall with her posse of blonde fixer-uppers. Paul Rudd is on, and O’Brien replaces a clip from The 40-Year-Old Virgin with one of a space alien falling off a cliff from the McDonald’s-sponsored movie Mac and Me. The publicist wails, “The studio is going to kill me!” Another night, members of Eva Longoria’s entourage, all in spangled attire and carrying tiny purses, titter in the greenroom. “Oh, Eva looks so beautiful,” they say. “Her makeup looks so good.” The show was supposed to send over a manicurist to Longoria’s place earlier in the day, but the woman never showed up. “Well, if they need to use her hands, they’ll use a hand model,” jokes an O’Brien producer.

The women look at each other, unsmiling.

We have all gone years without a decent sitcom, and you can’t really call the Law & Order franchise a great network drama—so would anyone really miss it if the late-night shill show disappeared into thin air? Is there something deep-seated in the American consciousness that makes us want to see stupid pet tricks and cozy conversation between host and starlet as we drift off to sleep, snug as bugs?

O’Brien is in the odd position of knowing that what he is inheriting is no longer as valuable as it once was but wanting it anyway. “There are no gatekeepers to comedy anymore,” says O’Brien, who hasn’t performed stand-up since college and rarely visits comedy clubs (the idea of hosting a stand-up show, he says, makes him want to “put a gun to my ear”). “There used to be a castle with one entry to the moat, and Johnny had the key to the drawbridge. Now they’ve taken down all the walls to the castle and people are milling in and out. These days, there are 40 ‘best new comedians’ coming out next year. I saw some comedian billed as ‘he’s so edgy he makes Chris Rock look like Bill Cosby.’ What? That’s slamming two great comedians for no reason. I think of it as, you have lots of instruments playing, and we’ve got a little triangle going ding-ding-ding! If we do it for a long time, people will eventually hear it.” He grimaces. “If it’s worth hearing.”

Stop the madness, Conan. I cannot bear to hear any more self-deprecation. Finally, it’s phony. And if I find it irritating, won’t much of America?

“Evangelist Jimmy Swaggart got in trouble recently when he said he would kill any gay man who looked at him romantically. In response, a spokesperson for gay men said, ‘Hey, we’re gay. We’re not blind.’ ”

Well, he’s working on it. “It sounds pretentious, but I do think of this as a body of work, and the next couple of years are really important, not the time to start dogging it, you know what I mean? After the announcement was made, I thought, There are only a finite number of these Late Night With Conan O’Briens left, and I want them to be good—there are people who might be checking me out now who weren’t checking me out before. I don’t want them tuning in and going,‘Well, what was all the fuss about?’ ”

Conan will inherit the crown—he’s the Prince Charles of late night. The geeks will inherit the Earth. And he’ll have no more excuses about being on too late—thank God.

Jeff Ross, O’Brien’s calm and debonair executive producer, also has a button he can push to make the door slam automatically, but today the door is open. He’s in there watching golf on the big-screen TV, a grid of index cards of the guests the other late-night shows have booked for the week pinned to a wall (The Daily Show is noticeably absent—“below the radar” is the way Ross puts it). He talks about what makes a good guest spot, and renovations on his house in Southampton, and in the most casual way whether O’Brien would be happy at another network or doing a different kind of show, what could be gained by leaving NBC and what could be lost—the most important job in comedy.

O’Brien strides in. “You see, we’re in it to win it,” he declares with a tight smile.

“We won it,” says Ross, shaking his head.

“Please stop talking,” says O’Brien.

FUNNY BUSINESS

Conan on the Couch

The lanky embodiment of New York comedy gears up to enter the living rooms of Middle America. The Ten Funniest New Yorkers You’ve Never Heard Of

The next Seinfeld, the next Sedaris (David and Amy), and the man behind the year’s most rocking TV ad. One Night. Five Open-Mike Shows. Hundreds of Lousy Jokes

A Monday spent on the front lines of comedy. Eight Things New York Comedians are Joking About

An informal survey of comedy-club bookers reveals the city’s most popular punch lines. How to Build a Joke

A dissection of a one-liner.