At Teddy’s Berry Street diner in Williamsburg, Kate Christensen is fighting a hangover. Looking tired and a bit wan, she slips out of her fake-fur coat and orders a Bloody Mary. It turns out she was up until three last night, carousing at a musician friend’s dinner party, lingering over a nightcap or two at a Metropolitan Avenue dive. “Usually I drink vodka,” she says. In fact, Christensen is such a connoisseur that she concocts her own. “Ginger vodka, horseradish vodka,” she says, flagging the waiter for a pot of tea to use as a chaser. “I’m trying out all kinds.”

Except for her wedding ring, the 36-year-old Christensen is a lot like Claudia Steiner, the vodka-swilling heroine of In the Drink, her first novel, which Doubleday is publishing in May. And though Claudia lives in a ratty Upper West Side studio instead of a Notting Hill flat, she happens to be a lot like Bridget Jones.

You have, of course, heard of Bridget, the self-obsessed centerpiece of Bridget Jones’s Diary and the brainchild of former London Independent columnist Helen Fielding. Daily dispatches from Bridget’s life, written in diary form and beginning with calories consumed, alcohol units imbibed, and Silk Cuts smoked, made Fielding’s quirky column a sensation in England. In 1996, she gathered them into a book. And while she took pains to distance herself from her character, there were certain undeniable parallels: Like Bridget, Helen worked in television, chain-smoked, and enjoyed the occasional drink. A short blonde with a pixie hairdo, she came off in TV appearances like your sweet, slightly feckless sister-in-law. In Britain, her book sold over a million copies.

Shortly afterward, Viking raced both Fielding and Jones across the Atlantic, where they stirred a similar sensation. Bridget Jones’s Diary leaped onto the New York Times best-seller list and remained there for seventeen weeks. Despite a few cultural discrepancies, many American women embraced the character with giddy self-recognition. She was a kind of resilient anti-heroine who veered between the pathetic and the courageous in her quest for love, sex, and an acceptable pair of opaque black stockings. In America, as in England, Bridget was embraced as an iconic thirtysomething Everywoman.

Naysayers, not surprisingly, dismissed her as an appalling bundle of feeble neuroses. In a cover story last June on the state of feminism, Time held Bridget up as an example of how far the institution has fallen. By then, however, it was too late. Bridget had already inched her way into countless Mexican beach bags, Upper East Side book clubs, and NYU dorms, inducting terms like Smug Married (blissfully happy member of a couple), Emotional Fuckwittage (stress associated with unreliable boyfriend), and Singleton (a woefully unattached character) into the lexicon. Today there are dozens of Bridget reading groups, a Website, several fan clubs. Fielding is currently at work on the screenplay and, of course, the sequel. “It’s much more than a book,” exults her U.S. editor, Pamela Dorman. “When you say Bridget, it conjures up a whole world.”

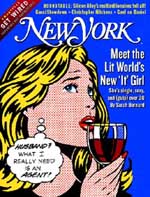

It’s a world that’s about to get a whole lot bigger. Long before Fielding arrived Stateside, Candace Bushnell had laid the groundwork by parlaying her pseudo-autobiographical New York Observer columns about Manhattan’s sex-obsessed swell set into a best-selling book, Sex and the City, and an HBO series, now shooting its second season. Laura Zigman’s Animal Husbandry covered some of the same terrain. But it was Fielding’s smash success that ignited this particular frenzy. Now the sullen Gen-Xers and self-indulgent soul-bearers of the past few years are giving way to the lit world’s newest prototype: a barrage of single, urban women, late twenties to late thirties, who struggle with loneliness and success with the help of a caustic sense of humor (and more than a few glasses of Chardonnay.)

In addition to Christensen’s In the Drink, there is Melissa Bank’s The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing and Suzanne Finnamore’s Otherwise Engaged. This summer will also see the debuts of Amy Sohn’s Run Catch Kiss, Clare Naylor’s Love: A User’s Guide, and Sue Margolis’s Neurotica, among others. Their publishers are frantically hatching marketing campaigns (from seminars on the single girl to bride-to-be Web promotions) in an effort to replicate Bridget’s success while struggling to get out from under her approximately 123-pound shadow.

There is a temptation to glean all kinds of cultural significance from the phenomenon. It wasn’t that long ago, after all, that women over 30 were relegated to the literary scrap heap, lucky to find a date, much less a book deal. In 1984, this magazine published a much-bemoaned study that claimed that women who were still single in their thirties had a better chance of getting hit by lightning than finding a long-term partner; that sense of desperation colored the way they were represented in fiction as well. But as the number of never-married American women more than tripled over the past two decades, the stereotype seemed dated. Now, if not always sympathetic, at least they have readers hanging on their every word.

Though Grove/Atlantic publisher Morgan Entrekin, who edited Bushnell and Fay Weldon, among others, is wary of literary trends, he believes that the boom in single-over-thirty protagonists may be driven in part by demographics. “Without question, 30-to-45-year-old women are currently the core readers of the fiction market. They are the strongest buyers and readers. It’s the same reason all the Oprah books do so well. If publishers are interested in these girls as characters, it’s because they are the ones who read these days.” (And it’s probably not a coincidence that many of the editors and agents acquiring the books are women in their thirties as well.)

“When I go on call-in shows to talk about thirtysomething women, every line lights up, the phones get jammed, the faxes start pouring in,” says conservative author Danielle Crittenden, who questions the notion that a modern woman’s career can replace a family life. Fielding modestly describes herself as merely the first to tap into a clearly emerging Zeitgeist. “Novels are like life, just a few years later,” she notes. “It just takes a long time for fiction to catch up with reality. It would be really arrogant,” she says, to take credit for empowering this crop of new novelists. “But I do like that idea. It makes me feel marvelous – like I’m the saintly benefactor!”

Undue concern for modesty doesn’t seem to trouble Candace Bushnell, who just returned from a triumphant tour of Bridget’s hometown last week. “They love me in London,” says the author, whose book maintains a firm slot on the London Times best-seller list and whose TV show recently made its European debut. (The show’s producers are now working on eighteen new episodes.) Bushnell, at 40, is like a walking character from her book: a pretty blonde with a penchant for power suits and powerful men. But while Bridget struggles vainly against her demons, Bushnell’s babes blithely embrace theirs. They live, as author Katie Roiphe observes, in “a prolonged state of adolescence,” wobbling in their stilettos from party to party. Bushnell believes that her books and others like them are successful because they give women an alternative to earlier stereotypes of single women. “That character has always been a cultural icon in America. There was Mary Tyler Moore, even Valley of the Dolls. But now, we’ve perfected the concept. I write about strong, funny people who do what the fuck they want.” She admits the new paradigm might be intimidating to some men. “For some reason, men don’t like funny. Funny is not a quality that’s usually prized by men. Large, fake breasts are.”

“Male writers have always featured characters like these,” Roiphe points out. “Promiscuous yet good-hearted young men trying to make their way through life. Look at Philip Roth or Jay McInerney. This is just the female version. Women in their thirties who are just living their lives, not depressingly hunting for a husband – they’re the new archetype.”

Melissa Roth, author of On the Loose, a nonfiction account of one year in three unattached women’s lives, reeled in William Morrow by selling the publisher on that very notion. “There was a time when single women in their thirties who didn’t have prospects would terrify people – family members, married women, everybody. Now it’s like they’re envied: They’re the ones with the exciting lives.”

Well, not always. In general, the new Lit Girls fall somewhere between Fielding’s muddled idealist and Bushnell’s exuberant hedonist. In some ways, they are the descendants of the angst-ridden postcollegiates who peopled the coming-of-age stories of late-eighties and early-nineties writers like Mona Simpson, Susan Minot, and Tama Janowitz. But their dilemmas are those of an older, more mature audience. “Coming of age is nothing,” says Christensen’s literary agent, Elizabeth Kaplan. “Being of age is where it gets interesting. There’s a whole generation of people who have grown up but are still struggling.”

When Christensen is not writing in her Greenpoint studio, the lithe, dark-haired author moonlights as a soap-opera star – albeit a low-rent public-access soap opera filmed in a friend’s living room. This is not her first foray into city-sponsored cable: An endless string of temp jobs included a stint reading (and writing) phone-sex scripts for Channel J. “I specialized in incest,” she notes. She began her novel over three years ago, while she worked as a secretary at a Japanese bank. At first, she desperately hammered her prose into what she labels “confessional serious American fiction”: “I remember trying to drudge up anything. But I wasn’t abused. I was never anorexic. If I showed an interest in science, my mother was right there with the chemistry set.”

Christensen says she quickly grew “sick of that self-seriousness. But I didn’t really see a lot of books out there until Bridget Jones that had a tone and worldview that was just like mine. I was reacting against political correctness, Alcoholics Anonymous. I love to drink! I think there’s a kind of moralizing in those books that I consciously reacted against.”

Like her contemporaries, she infuses her work with bawdy detail and cutting humor, traits that are a welcome change for readers who’ve suffered through the decade’s most recent literary trend: ponderous, weepy memoirs like Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation and Caroline Knapp’s Drinking: A Love Story. “Look at how violently people responded to The Kiss,” says Roth’s literary agent, Elizabeth Sheinkman, referring to Kathryn Harrison’s memoir about her four-year sexual affair with her father. “That was the apex of the memoir trend. People became fed up with the role of the victim. The independent spunky creature seems much more appealing.”

Christensen’s novel is an artful chronicle of a frustrated writer, Claudia, who finds herself light-years from where she expected she’d be. (She even has a dysfunctional relationship with her cat.) But Claudia doesn’t let her problematic obsessions veer into self-pity. Instead, she ponders electrocuting her psychotic boss in the bath and drinks vodka like it’s diet Snapple. As for the feminist standard-bearers who find Bridget Jones (and by extension her sister heroines) too frivolous, Christensen heartily disagrees: “We’re past the point where we have to prove we’re worthy by taking ourselves seriously. Feminism has brought us to the point where we can make fun of our weight. The time has come for women to be funny.”

Perhaps the most buzzed-about beneficiary of the Bridget boom is Melissa Bank’s The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing, which is not a straight novel but a collection of interlocking short stories. Although they seem to be having a small renaissance, collections are known to be consistent money losers and a tough sell. Bank’s stories, however, came with solid, savvy prose, a snappy title, and built-in momentum. The title story was originally commissioned by Francis Ford Coppola for Zoetrope: All-Story, his literary magazine. Coppola, who also commissioned Bank to draft a screenplay of the story, wondered what it would be like if someone followed The Rules, the oft-reviled how-to guide for snaring a husband.

In “Girls’ Guide,” Bank’s heroine attempts to employ the so-called wisdom of a book entitled How to Meet and Marry Mr. Right to snag a buff bachelor she meets at her best friend’s wedding. Throughout the narrative, the how-to book’s bouncy authors materialize as characters, dispensing unhelpful advice on the rules of courtship. “Melissa really made this idea her own,” says Coppola. “It could have been superficial or glib, but she took the opportunity to make it personal.” So personal that Jane Rosenal, her affable main character, is a ringer for Bank. “Obviously, I feel some of the same things,” she says. “Somebody should give you a guidebook to life. The wisdom we have is woefully inadequate.”

At Cal’s Restaurant & Bar in the Flatiron on a balmy spring evening, Bank, dressed in an all-black ensemble, is chain-smoking Merit 100s and drinking red wine as the after-work singles scene rages on around her. Everyone is eating oysters. Bank, who is 37 and single, grew up in the Philadelphia suburbs. She got her M.F.A. at Cornell, and after floundering for a while in various assistant jobs in publishing, she set her sights on magazines.

“I had an interview at the New Republic,” she recalls, “so I decided it would be a good idea to read an issue. There was one cool article, but other than that, I was totally lost. Some people grow up in an intellectual environment. I am not one of them. The only thing I can debate fluently is the evolution of hairstyles.” Instead, she lived with her mother and took the train to a temp job at a bank. “I wore my floral dress from high school,” she remembers. “That’s when you have a sense of yourself falling off the world.”

Eventually, she landed a copywriting job at McCann Erikson. “I had to write an ad convincing a monk who’d taken a vow of silence to use AT&T,” she recalls. After she came up with “AT&T. Because we take your vows as seriously as you do,” the firm ordered her some business cards. She continued to work on her writing; in 1993, she won a short-fiction contest at the Chicago Tribune. Then came Zoetrope, and after seven years of direct-mail ad campaigns, she sent her collection to agent Molly Friedrich on a Tuesday, along with this note: “Dear Molly, I hope this is a book. I also hope for the love of a good man.” Friedrich told her a sale would be “pathetically easy.”

On Wednesday, Carole DeSanti, Bank’s editor-to-be, read the manuscript, had an intensely physical reaction – “It was like someone shocked me with an electric prod,” she says – and came in with an offer of $275,000. A few months later, Bank received a letter from a senior buyer at Barnes & Noble, who sees hundreds of books a month, telling her he couldn’t get it out of his mind.

It’s clear that Bank’s book would have come to life even without a push from Bridget. But sharing the same publisher didn’t hurt. As they did with Fielding’s book, Viking’s marketing staff is planning to pile into a van postered with the book’s cover and drive to city bookstores like a roving pep rally. The publisher, which has already tripled the first printing for Girls’ Guide, plans to trot out Bank and Fielding together this summer; the women will be appearing at the 92nd Street Y to chat about “what single girls want.” Bank doesn’t mind the association at all. “It makes me annoyed that Bridget was so slammed,” she says. “She gets at a lot of truths about what it is like to be a single woman, in sort of a middle-class, better-than-average job, trying to find love. I thought it was beautifully done. If it had been the diary of a male coal miner, it might have been hailed as great literature.”

As she somewhat sheepishly admits, Suzanne Finnamore may be the only tyro in the publishing world who has yet to crack Fielding’s tour de force. “I’m too upset about the fact that she’s picking out a Honduran island right now,” she quips. “I find that gets in my way of reading it.” But Finnamore, who had a solid career as a creative director at Foote, Cone & Belding in San Francisco, may soon be flipping through the Sotheby’s island catalogue herself. Last summer, literary agent Kim Witherspoon plucked the manuscript of her first novel, Otherwise Engaged, out of a slush pile and quickly submitted it to publishers. At the time, Finnamore was nine months pregnant.

“We were going back and forth via cell phone,” Finnamore recalls. “Meanwhile, I’m driving to the hospital for my C-section.” That afternoon, she pocketed a hefty six-figure advance from Knopf. A few days later, 20th Century Fox stepped in to option the movie rights, and she whisked her week-old son, Pablo, straight to the BMW dealership. “I put him down on the desk and told the guy he had an hour,” she laughs. “Now I have a 528i with Montana leather interior and a 400-watt stereo. It’s a crack dealer’s car.”

Although she’s the only one of the bunch who is also a wife and a mother, Finnamore is far from a “Smug Married.” A brassy Californian with cropped, dark hair, she fires off one-liners like a stand-up comic. Her heroine, Eve, is a 36-year-old creative director in San Francisco who artfully orchestrates her engagement, then comedically suffers through the ensuing year of ambivalence. “Insta-Shrew,” Eve calls herself after barking at her new fiancé, “Just add diamonds.” The narrative is divided into monthly dispatches, peppered with hilarious tag lines. Eve’s conceptualization of a prune campaign reads as follows: “Little. Black. Wrinkled. Prunes! Prunes … they used to be plums.” She is also appropriately neurotic, as Finnamore is quick to emphasize. “But she’s more like Scarlet O’Hara-neurotic,” she explains. “She’ll bite your arm off. She’s like Bridget, but butch.”

Knopf is betting that Otherwise Engaged will be a “big book”; ordering up an initial run of 75,000. But its release next month will put it directly in the path of Bridget’s paperback debut, on May 24. Viking plans a blitzkrieg release of 460,000 copies, with all the attendant fanfare. Fielding herself touches down for a frenzied round of morning shows and book signings June 1. Tellingly, her stops will include Bloomingdale’s as well as Barnes & Noble.

While Finnamore jokes about Bridget’s omnipotence (“Bridget is like Jesus Christ. Everything is B.B., before Bridget. We’re P.B., post-Bridget!”), her publicist is alert to the risks in the comparison. As Katie Roiphe notes, the fascination with the thirtysomething single gal could have a limited shelf life. “The genre has a danger of being annoying,” she says. “It’s like Ally McBeal. It was interesting in the beginning, but you can’t stand that much of it.” In England, Bridget has devolved from an icon into something of a punch line. “Her moment is so past,” sniffs Sally Ann Lasson, who writes Tatler’s “Sex in Society” column. Even the Bridget Jones movie, which Fielding is writing for Working Title Films (Four Weddings and a Funeral), is rumored to be on hold because of the book’s overexposure.

Detractors wouldn’t be sorry to see the genre wear out its welcome. To Danielle Crittenden, the Lit Girls’ spirited high jinks mask a real anxiety that still accompanies the state of being single in your thirties. It’s an opinion shared, somewhat surprisingly, by Marcelle Karp, the 35-year-old cofounder of the femzine Bust. Many of the new books, she points out, paint single life as a long, sexy party: “Everyone gets laid a lot and wears Prada. But they’re glamorizing something that is vaguely uncomfortable. The reality is, single women in their thirties are only going out to fill the void. I don’t know one woman who doesn’t want a boyfriend. If she’s single and 35 and saying she doesn’t want children, she’s only saying that because she’s afraid she won’t have them. I go out every night of the week because it’s better to go out than be home alone.”

“Single women today may have lots of problems,” counters the 40-year-old Webzine editor Marisa Bowe, “but they’re certainly having more fun than their mothers did. Which is better, to be single but lonely sometimes or be stuck in the suburbs, carting your kids around to their lessons while your husband is gone all day and people make you feel like you’re a moron? That’s why Valium was so popular.”

Last Tuesday night, at Kate Bohner’s 32nd-birthday party, there was no Valium in sight but plenty of other libations available. The festivities, held at a spanking-new apartment in Trump’s Riverside Boulevard complex, seemed like a scene from a Bushnell book come to life. Bohner and Bushnell are, after all, best friends, but tonight Candace, stuck in England, couldn’t make it. (She called from the plane.)

Bohner, looking fetching in a light-blue sheath, a matching shawl tucked under her spaghetti straps, stood by the bar in a huddle with the women she calls the Sisterhood: a group that includes Sarah Colleton, who produces movies with Penny Marshall, and the novelist Karen Moline, whose second novel, Belladonna, sold for a million dollars. Both are, of course, still single. Around them, several dozen guests – carefully groomed and studiedly casual women – guzzled chilled Dom Perignon. Nobody bothered with the hors d’oeuvre.

“There was a time when turning 32 would have seemed scary,” giggled Bohner, who had been an investment banker, a Forbes columnist, and a CNBC correspondent all before she was 30. “Now it’s like, fuck, who cares! We take care of ourselves. It’s the way plate tectonics works in socioanthropology,” she explained, pouring herself another glass of champagne, and coolly surveying the room.

“The New York scene is like continents that shift. There are more thirtysomething women now than ever before. We’re the genre with the biggest continent.” She laughs. “And we’re moving in on everybody else.”