Vase de Fleurs (Lilas) is not one of Paul Gauguin’s greatest works. It’s a “middle market” painting, which means it changes hands usually for only a few hundred thousand dollars, and without much fanfare. But in May 2000, the painting proved it could still turn heads. When Christie’s and Sotheby’s released spring catalogues for their modern-art auctions, they were alarmed to discover that each was offering the painting—and each house thought it had the original.

One of the paintings, clearly, was a fake. So the auction houses flew both paintings to Sylvie Crussard, a Gauguin expert at the Wildenstein Institute in Paris. She put them side by side and in a few minutes saw that Christie’s version was, in the delicate argot of the trade, “not right.” (The auction house just barely managed to yank its catalogue back from the printers in time.) Still, it was the best Gauguin counterfeit she’d ever seen. “This was a unique case of resemblance. You never see two works which are that similar,” Crussard marvels.

Christie’s broke the news to the horrified owners at the Gallery Muse in Tokyo, who’d had no idea it was a forgery. The real painting went back to Sotheby’s, where its owner—New York dealer Ely Sakhai—successfully auctioned it off for $310,000. But when the FBI traced the history of the fake, they discovered something even more surprising: The original source was none other than Ely Sakhai, too.

According to the FBI, Sakhai had bought the real Gauguin years earlier, cranked out a duplicate, and sold the illicit copy to a Tokyo collector. Then Sakhai brazenly put the original up for auction, in an attempt to double his profits. It was a pure fluke that the unwitting owner of the Tokyo forgery decided to resell his copy at the same time. But for that coincidence, the forgery might never have been detected.

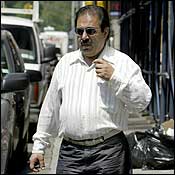

The more the FBI pulled threads, the more fake paintings it uncovered—all Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, and all traced back to Sakhai. On March 9, agents arrested him at his gallery on Broadway south of Union Square, a storefront crammed with antiques and paintings. They charged him with eight counts of wire and mail fraud. Sakhai had allegedly been running one of the most audacious forgery scams ever—a multi-million-dollar operation that has left art experts alternately amazed by his legerdemain and stunned by his shamelessness. In each case of forgery, the complaint says, Sakhai bought a little-known painting by a modern master, faked it, and then sold both the knockoff and the real one. To keep the duplicity hidden, he allegedly sold the fakes to buyers in Asia, the real ones at New York and London auctions. In total, the scheme grossed $3.5 million, according to FBI estimates.

But what was perhaps most interesting was how well this hustle exploited—and exposed—the frailties of the art marketplace. It is a world in which surprisingly few people are willing to stick their neck out and call a fake a fake, so that even as Sakhai’s scheme racked up victims, virtually no one was willing to call him on it. The forger knew this secret of the art world: It is tolerant of frauds, so long as the victims are in far-off places like Tokyo and too humiliated to raise a fuss. As if delivering a judo move, he used the particular quirks of art dealers against them. “We’re talking about a very, very clever scheme,” a former Christie’s modern-art specialist says.

Ely Sakhai would not, at first blush, seem to be a likely international man of mystery. He flew under the radar in the city’s art scene, rarely appearing at parties or art events. Before his arrest, many New York gallery owners had never heard of him.

The dealer with the low profile emigrated 35 years ago from Iran, and quickly established himself as a successful dealer in antiquities. He became known in the Iranian-American community of Old Westbury, a wealthy Long Island suburb. In the local restaurants, Sakhai is a familiar sight, showing up with his Japanese wife and groups of Iranian art-trade friends. He’s also beloved among the area’s ultra-Orthodox Chabad Jews, not least because he paid to build the Ely Sakhai Torah Center—a modest building that houses a few classrooms, run by Rabbi Aaron Konikov, who wouldn’t comment on the charges. “There are a lot of nice stories you could tell about this man” was all he’d say.

In Sakhai’s professional life, though, the stories were rather less pleasant. In the late eighties, he began to show up regularly at Christie’s and Sotheby’s to buy Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works. He cut an unusual figure: A short man with a Clark Gable pencil-line mustache, he was a reserved figure, except for his outlandish outfits. The former Christie’s specialist remembers seeing Sakhai arriving in “cowboy boots and fringed stuff”; one dealer recalls a purple suit. Sakhai later switched to more conservative clothes, but he always carried himself like royalty. “He’d have these big, expensive rings. When you looked at him, you could tell there was money there,” says the dealer.

Though Sakhai bought famous artists like Chagall, Monet, and Laurencin, he didn’t buy their A-list art. He stuck exclusively to cheaper, lesser-known works of no more than a few hundred thousand dollars, tops. Still, “he made an impression because he bought a lot of work,” as the specialist recalls.

Soon, curious stories began to emerge—almost always from people in Tokyo who said they’d dealt with Sakhai. Flush with cash in the nineties, Tokyo companies and collectors had developed an enormous appetite for Impressionist work, and Sakhai apparently found many eager buyers in the “Tokyo bubble.” For example, the FBI says, in 1990 Sakhai bought La Nappe Mauve by Marc Chagall at a Christie’s auction, for $312,000. Three years later, he sold what appeared to be La Nappe Mauve to a Tokyo collector for $514,000. The collector resold the painting, too, and after it switched hands a few times, the new owner put it up for auction at the Galerie Koller in Zurich.

The gallery’s director, Cyril Koller, was about to put the painting on the cover of his auction catalogue when he got, he says, a funny feeling. He decided to look into its authenticity. Sakhai had originally sold the painting with an accompanying certificate issued by the Comité Chagall, a French organization that authenticates all Chagalls. Koller faxed the certificate to France for verification; it checked out. But Koller was still suspicious, so he compared the painting closely to a photograph of it on the certificate. He noticed that the brush strokes were off, and “the colors were strange, a little bit,” he recalls. It was a fake.

Koller had figured out the key element of the forger’s scheme: When he copied a painting, he took the genuine certificate of authenticity and slapped it on the duplicate—thus making it much easier to pass off. Any buyer who looked at the certificate would assume the counterfeit was real. And the original painting could be sold with confidence later on, sans certificate, since it was the genuine item. In fact, Sakhai did precisely that: In 1999, he sold the real La Nappe Mauve at Christie’s for $340,000.

The scheme had one obvious risk, of course: the existence of twin paintings. Over time, several surreal situations emerged in which two seemingly identical paintings cropped up at the same time, like models arriving at a party wearing the same “unique” designer gown. According to the FBI, Sakhai sold a forged copy of Marie Laurencin’s Jeune Fille à la Mandoline to a Tokyo buyer in 1995 for approximately $28,100 (the buyer paid by trading two paintings of combined equal value). The painting was resold a few times and then eventually consigned for auction at Christie’s in 1997—whereupon Christie’s realized that Sakhai also owned the same painting. In another case, a buyer sent to Christie’s a Marc Chagall, called Les Maries au Bouquet de Fleurs, that he had bought from Sakhai. The auctioneers initially sold it for $450,000, then realized that it was a fake; they then rescinded the sale and sent the painting back to its owner. In 1998, a buyer in Taipei reportedly paid Sakhai $80,000 for a supposed Chagall, Le Roi David Dans le Paysage Vert, as well as a Renoir. When he sent Le Roi David to the Comité Chagall for verification, the group declared it a fake—whereupon the French authorities destroyed it. Sotheby’s later discovered that the Renoir was bogus as well.

Soon, enough Asian customers had been burned that word began getting out about Sakhai. Kara Besher, owner of Maru Gallery in Tokyo, had a client who was interested in a Sakhai painting—a “large, gorgeous Modigliani, desirable year, stellar provenance”—but wanted Besher to examine it. Besher met Sakhai at Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, where he would often conduct sales while in town. He introduced himself as a French art dealer, and Besher was alarmed to see that he’d stacked several apparently valuable paintings casually against the wall. He brought out the Modigliani. She was unimpressed.

“I am not an expert in the artist’s work,” she later wrote in an e-mail, “but the painting didn’t evidence the signs of age one would normally expect. It looked almost comically fresh and new.” (She leaned in closely to see if she could smell fresh paint, but her nose was overwhelmed by Sakhai’s cologne.) She advised her client against buying the painting. Another gallery owner, Y. Mano, also met Sakhai at the hotel, where he was shown works by Monet and Laurencin. He, too, declined: “Fake,” he says bluntly. “No good.”

In the U.S., even the auction houses were beginning to cast a suspicious eye toward Sakhai. Sure, the paintings he was selling would check out fine: They were, after all, real. But Tokyo collectors kept claiming they had the same ones. “Every time we put a painting from [Sakhai] in, we’d get a phone call from around the world saying, What are you doing with my painting?” says the former Christie’s specialist.

They began to question Sakhai more closely; Sakhai denied having anything to do with the fakes. On the contrary, he noted, he often consigned paintings to other dealers—so who knows what happened while the paintings were out of his control? The questioning didn’t seem to faze him. He was “very matter-of-fact” about it, the specialist adds: “Not aggressively defensive.”

Yet one Manhattan antiquities dealer familiar with Sakhai says he, too, noticed clues. For example, he says, Sakhai would regularly buy up old, rather worthless paintings. They’re known to be useful in forgery circles, since a forger can paint a dupe on top of the old canvas, giving the fabrication a facsimile of age. “Everybody who was selling them to him would know what he was doing with them. He wouldn’t care what the painting was,” says the dealer. “It’s been notorious.”

By the late nineties, Special Agent Jim Wynne of the FBI in New York had begun to make inquiries. The FBI will not comment on its investigation, other than to say it took “longer than a couple of years” to assemble the case. But as Wynne interviewed art dealers in New York and Tokyo, Sakhai learned that the noose was closing around him. “Mr. Sakhai has been keenly aware of the existence of this investigation … for close to five or six years at this point,” Sakhai’s lawyer, James Keneally, noted at Sakhai’s initial court appearance on March 9. Indeed, he added, Sakhai “knew beyond any doubt” that the FBI was preparing to move in and have him charged.

If it took a long time for the FBI to bring Sakhai in, observers say, it was probably because international forgery scams are notoriously complex. The FBI would have had to cooperate with police forces in several countries, hunting down dealers undoubtedly reticent to discuss how they’d been hoodwinked. Besides, the art experts are French, the collectors are Japanese, and the need to translate everything seems to have impeded the process.

At least one mystery remains: To this day, the FBI agents do not know who actually painted the forgeries. Copying of a painting is itself not illegal; it’s only when you try to sell it as authentic that it becomes fraud. Some experts say the painter is unlikely to have been American, because American art schools now rarely teach traditional oil technique. They suggest that a more likely place is China, which is flush with ultracheap labor. “The Chinese have a lot of people doing it,” says Denis Dutton, an art expert and professor at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand. Given the high quality of the Gauguin copy she saw, the Wildenstein Institute’s Sylvie Crussard thinks the painter must have been young and vigorous. “You can’t be old,” she says, “to do that.”

When news of Sakhai’s arrest reached the art world, dealers had one question: How did such a nervy scheme go undetected for so long? “What’s just phenomenal to me is that he’d sell the real [paintings] publicly,” says Warren Adelson, president of Adelson Galleries, which specializes in Impressionists. “It’s like a death wish or something. It’s like a B-movie.”

Yet the forger’s success may lie in the art world itself—and how deftly he navigated its politics. By avoiding the New York market, he ensured that he’d generate little local heat. Moreover, Japanese art buyers are particularly reliant upon certificates of authenticity; because they’re so far from Europe, Tokyo collectors do not have easy access to the experts who can spot a fake Chagall at 50 feet. As a result, “the Japanese are famous for being kind of obsessed with certificates of authenticity. They’re almost more important than the actual painting,” says Judd Tully, editor-at-large of Art & Auction. A forger who transferred a real certificate to a counterfeit could be sure that few Japanese experts would spot the deceit. What’s more, since the paintings in question were not famous, few experts would be familiar with them, making it less likely someone would notice a fake. (A Japanese buyer might fly an expert in from Paris to authenticate a $20 million painting, but not a $500,000 one.) Culture helped out, too. When Japanese dealers discover they’ve been cheated, they’re less likely to raise a fuss than European or American ones, because they feel ashamed.

But the alleged scam also relied on one unexpected fact. In the art world, crying “fake” is surprisingly difficult. One might imagine that dealers are manic about authenticity and would be quick to publicize any possible chicanery. But when million-dollar reputations are on the line, openly claiming that someone else has been suckered—or complaining that you have been—can get you slapped with a libel suit. Even when a dealer spots a clear forgery, few people are willing to burn bridges by speaking out.

In the art world, crying “fake” is surprisingly difficult. Even when a dealer spots a clear forgery, few people are willing to burn bridges by speaking out.

“What’s your motivation if you see a forgery on the wall at Sotheby’s?” one New York dealer says. “What are you going to do—raise hell until they begrudgingly take it down? No. You think, Maybe I won’t mention this.” Indeed, the dealer criticizes Christie’s and Sotheby’s for doing a lackluster job of spotting the Impressionist fakes. In some cases that the FBI examined, when a collector unwittingly consigned one of the forgeries to auction, the houses blithely listed it in their catalogues—discovering the fake only after receiving puzzled phone calls from Tokyo.

As you’d expect, this sniping annoys the auction houses. “We do our best” to verify authenticity, says Christie’s spokesperson Andrée Corroon. That means not merely giving the artwork a smell test but tracking the paperwork for as many previous owners as possible. Yet even when a fake is suspected, the repercussions can be mild. Auction houses don’t consistently turn a suspected forgery over to the police; they can just send it back to the owner. If the owner doesn’t want it, the auction house sometimes keeps the painting, taking it out of circulation, according to Corroon. And, as observers point out, the sheer economics of the business means that auction houses can’t afford to lavish days on the history of each “middle market” work that brings in only a small commission. “If it’s not a $5 million picture, it’s not the bread and butter,” Tully says. By sticking to lesser-known paintings, the forgery scheme neatly leveraged this market reality.

It is also likely that a plot of this sort could never work again. When the forging scheme began, it was the early nineties, and communication between the U.S. and Asia was much slower. A decade later, when every auction incorporated online bidding and most galleries had Websites, victims could quickly figure out the scam’s central flaw: that a single painting was in two places at once. “Maybe he was sort of living in the past,” muses one New York dealer. “Today, with the Internet, people get the message really, really quickly. It was an astonishing story.” For a forger to pull off a similar scheme today, he’d have to avoid the auction houses altogether, and do everything extremely quietly, through private dealers. Or, like a few great forgers of the past, he’d need to invent “lost” works from scratch, in the style of great artists, with no originals to trip things up—requiring the rare, talented painter who can pull it off.

As for Sakhai himself, he’s still out on bail, and still drives in from Long Island to visit his Manhattan gallery. Customers still come by to assess nineteenth-century candelabra, Victorian vases, the paintings that crowd the walls. But Sakhai isn’t talking; at one point, he calls up to explain, quietly and politely, that it wouldn’t be in his interest. “To be honest, I wanted to come and talk to you,” he says, “but my lawyer advised me don’t. I wish I could.” And then, muttering a quick thank-you, he hangs up.