Sam Peabody, scion of an old New England family and husband of the socialite Judy Peabody, lives in a duplex at 990 Fifth, as desirable an address as there is in New York City, decorated in impeccable East Side style. Childe Hassam paintings hang on the walls, and side tables sparkle with collections of pink jade, antique porcelain, and Russian lacquered boxes. It’s a glorious cocoon, one in which the shades are often drawn—Peabody would prefer not to have to think about the Metropolitan Museum, directly across the street.“They haven’t been direct with us,” the soft-spoken Peabody says while sitting in his high-ceilinged library. “I know there are some people who feel very strongly about how the Met is handling this, and do not want to be hearing dynamite and traffic.”The Met has long been the jewel in the crown of the Upper East Side, a sprawling wedding cake of a building celebrating the marriage of art and money. It’s arguably the greatest museum in the world, with the most comprehensive collections, and the most illustrious board in the city, the preferred clubhouse of Astors and Dillons and Lehmans. The museum’s vast troves cast their glow over the whole neighborhood. “We felt it a privilege to be living so close to this treasure house,” says Peabody.In the past few years, however, some of the museum’s neighbors have begun to see the Metropolitan less as a refined repository of priceless cultural artifacts than as a tacky tourist attraction of idling school- and sightseeing buses, souvenir sellers, and street performers—far more democratic than Fifth Avenue has ever considered desirable. Then, in 2000, the Met threw down the gauntlet, pushing a plan through the Parks Department that called for a 200,000-square-foot expansion (over 300,000 if you believe the opponents) including digging out the fountains to build new storage vaults. The renovation was to be the capstone of Met president Philippe de Montebello’s tenure, his response to the relentless modernizing that his predecessor, Thomas Hoving (he installed the fountains, and the Temple of Dendur, and much else), had done in the sixties and seventies. The neighbors formed the Metropolitan Museum Historical District Coalition, to attempt to have a voice in the renovation. “In the beginning, I thought when we spoke to the Met, they would be cooperative,” says Anne Cumito of 1001 Fifth Avenue, a coalition member. “They’ve been very patronizing and condescending—‘We’re the Met, and who are you? You just live here.’ ” Peabody concurs. “I do think they handled this quite arbitrarily,” he says. “It’s too bad we couldn’t have sat down together.”“What, did they wake up one day and just find a museum across the street?” wonders Barry Schneider, a member of Community Board 8, where much of the dispute has played out.The coalition filed suit to stop the project in its tracks. A ruling went against it in May, but the judge suggested that the case had merit, and that gave it maneuvering room for an appeal. The coalition is optimistic. Henry Stern, the Parks commissioner who signed off on the project in 2000, asserts the fight is less about governmental due diligence than social envy. “People set themselves up against the trustees, against Kissinger and all these famous names,” he says, referring to the Met’s board of directors. “They want to beat the A-list. If you can’t join the A-list, beat them.”But if the museum’s opponents suffered any self-doubt about the righteousness of their cause, that vanished when Thomas Hoving volunteered to lobby on their behalf. “I was riled,” Hoving says, when he heard of the Met’s plans for his fountains. “I built the fountains and the grand staircase. That got me dorked off.”

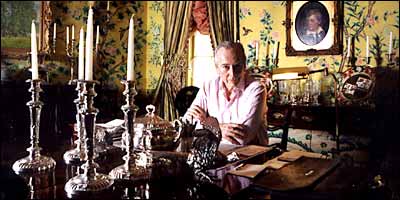

“I was riled,” admits Thomas Hoving, when he heard of the Met’s plans for his fountains. “That got me dorked off.”

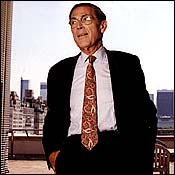

Hoving, of course, is the man who woke up the museum from its upper-crust slumber, transforming it into that cultural tourist attraction. Hoving, who quit his post as John Lindsay’s Parks commissioner in 1967 to head the Metropolitan, was a sixties culture hero, Fifth Avenue’s answer to the yippies, a brash impresario with a virtuoso gift for publicity—and self-publicity. It was Hoving who hung the banners, brought the buses, enlarged the shops, beefed up the collections. Now, ever the provocateur, he’s trying to make De Montebello move in the opposite direction.Hoving is accusing De Montebello and the Met of mismanaging his legacy by violating a master plan—to hear him tell it, the master plan literally to end all master plans—that he hammered out with the city back in 1971. Its salient feature was that the Met would cease to mushroom, which it has clearly failed to do.Hoving himself was an eager mushroomer, shifting course only when he was forced to. “We wanted to expand further,” Hoving says of his negotiations with then–Parks Commissioner August Heckscher. “We were thinking of building a luxury hotel on top of the museum. He said, ‘Screw it.’ ”“We had to slow down collecting and had to loan quite a bunch of stuff out to the boroughs and other museums,” he goes on, ticking off other parts of his plan he claims the current Met has failed to honor, such as opening the museum to Central Park. Furthermore, the museum would “only acquire those things that were better than what we had. We felt it was getting too big, and now it definitely is. Plus, the traffic situation out there on Fifth Avenue has gotten to be Buenos Aires, and the steam coming out of the air-conditioning units—enormous clouds.”How did Philippe de Montebello react when told about Hoving’s charges? “I laughed,” he says, in his Anglo-French-accented baritone familiar to anyone who’s taken an Acousti-tour of the Met—it’s his voice that is on the recording. “Preposterous!”It must be infuriating for a man like Philippe de Montebello to have his predecessor buzzing in his ear. His pedigree is illustrious (in fact, he’s a count). On his mother’s side, De Montebello is related to the Marquis de Sade. A great-grandmother was a model for the Duchesse de Guermantes in Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. De Montebello worked under Hoving as the Met’s vice-director for curatorial and educational affairs. In 1977, he replaced his mentor as head of the Met, in the hope that he would inaugurate an era of peace after a decade of Hoving’s endless public controversies. At the time, many questioned whether he had the academic background and activist personality necessary to lead an institution of the Met’s complexity. Instead of Hoving’s mad creativity, De Montebello brought management skills, a conservative approach wrapped in an imperious old-world package and an occasionally theatrical manner—which, some have said, he learned partly from Hoving. A seventeenth-century desk, laden with ormolu, features a sign that says LE CHEF TOUJOURS A RAISON. The desk faces a large Arcadian Claude Lorrain landscape—the more perfect world that might exist without, say, a certain former director. Now De Montebello is in a box, though admittedly a splendid one. He has to change the museum, modernize it, move it forward, without changing its footprint. And meanwhile, the neighbors—and Hoving—are fighting him over every detail.“Obviously, a museum cannot remain static or it loses its cachet,” says De Montebello. “The sustained interest of the public is based on collections that are not static, that continually change, on programs that are different. We live in a society and a world where the notion of a completely fixed site doesn’t capture the imagination. Lying down and playing dead is not a good policy.”De Montebello’s light-filled office opens onto an immense patio and beyond it the Met’s spreading wings, atriums, courtyards, and crystalline add-ons. The overall impression is reminiscent of being on the captain’s deck of a great ocean liner, with Central Park off in the distance. De Montebello jokes that a photographer has placed the park behind him in a portrait to suggest his land-grabbing designs on Frederick Law Olmsted’s masterpiece.

To hear De Montebello tell it, the greatest change visible from the outside when the renovation is complete will be a reduction of the size of the banners advertising the Met’s latest exhibitions. “You would see the great new classical façade is gleaming,” the director says. “As you know, we are cleaning it now. You would see that great respect has been paid to the architecture with the redesign and the reconfiguration. We’re no longer going to have the banners which we now furl and unfurl on the façade, that are huge and that cover totally the glass arches that let light into the Great Hall. Obviously, you have to announce and give a sense that one is not an inactive institution. But they will be smaller and be dispersed within the architecture. On the inside, I would hope there would be substantial changes.” De Montebello’s $150 million improvement plan is hardly unambitious. It includes lifting the roof off what was, until June 2003, the Met’s cafeteria, to create a two-tiered court for the museum’s Roman-sculpture collection, much of it currently in storage. Adjacent galleries will display a new Hellenistic Treasury, the Cubiculum from Boscoreale (a bedroom from an ancient Roman villa), and the Met’s celebrated Etruscan chariot, which is being renovated at the moment. The Ruth and Harold D. Uris Center for Education is also up for more than a splash of fresh paint, with new orientation areas, lockers, an art studio, an art study room, and a state-of-the-art 300-seat auditorium.Further improvements include new galleries for the nineteenth-century, modern-art, and photography departments—the Met recently announced plans to give MoMA a run for its money by expanding its modern- and contemporary-art departments—new offices, renovations to the Islamic-art galleries, and, up the line, reshuffling the American Wing. Only then, De Montebello believes, will the Met be fulfilling its mission as the world’s most, and perhaps only, encyclopedic museum, where the day-tripper can go from Hellenism to Damien Hirst in a single afternoon. Actually, he already believes it’s fulfilling that mission nicely. “We are the world’s greatest encyclopedic museum, by a wide margin,” he says.Sam Peabody wants to make absolutely clear that he appreciates his proximity to Monet’s Water Lilies and the Met’s incomparable collection of Oceania. He’s even broken bread with De Montebello, though before the current ugliness. They met through a cousin of Peabody’s. “He’s a very cultured guy, a bright guy, an interesting guy—good company.“I think it would have been helpful if he’d wanted to listen,” Peabody continues. “My impression is that he doesn’t want to be part of this. That’s why he has David there.”He even likes David McKinney, the Met’s snow-white-haired president and De Montebello’s designated front man, whom Peabody called to protest when he was awoken this winter in the middle of a snowstorm. “They got out their snowplows at 2:15 in the morning,” Peabody complains. “You could hear them for an hour and a half. I called Dave McKinney the next day—he lives up the street, at 993—and he looked into it. He said they had no say in the subject. They were obligated to clear the place for people catching buses, which doesn’t make much sense to me.”He and his wife also recently lent the Met one of their Childe Hassams, A City Fairyland, for its current exhibition. (Peabody says he didn’t try to exact concessions from the curatorial staff on behalf of the coalition in exchange for the painting. “The left hand does not know what the right hand is doing,” he says of the museum.) Susan Aberbach, an art dealer and the coalition’s secretary, bristles at Stern’s suggestion that it’s waging a social vendetta against the trustees. “I don’t even think the board is aware of what their executives are doing,” she says, noting that her family donated a major painting by the Belgian Surrealist Paul Delvaux to the museum. “I don’t even know if these people attend board meetings. I don’t even know who they are—and that’s not the issue. The issue is the sanctity of our homes.”Pat Nicholson, the MMHDC’s supreme commander, whose apartment at 1016 Fifth overlooks the museum, certainly isn’t the stereotypical social climber. “Pat’s an Irish girl from the projects,” says Ed Hayes, the lawyer who represented the coalition in its early days. “She’d be perfectly happy as a sergeant in the Police Department. That’s what God intended her to do. I don’t know where she went wrong and ended up on Fifth Avenue.”Where Pat Nicholson went wrong was in marrying her boss, Ronald Nicholson, a real-estate developer and horse breeder, who says he sometimes awakens at 4 a.m. to find his better half pounding away at her computer on MMHDC business. “I told their lawyer not to get into a fight with my wife,” he says of the Met. “She’s the best-organized person in the whole world. It took Eisenhower a year to plan D-Day. She could have done it on a long weekend.” Pat Nicholson’s particular bugaboo is the mechanical equipment atop the museum, the air-handling systems that keep all those Vermeers and Van Goghs new-looking, and of which she has a bird’s-eye view from her bedroom window. The equipment also apparently produces copious amounts of vapor at certain times of the year that cloud her windows and obscure her views. She has documented these mists, through both video and still photography.“Nobody would be in it the way I’m in it to protect their views,” she claims. “For 150 years, they’ve never put themselves in a place where they’ve had to be accountable. Void the lease. Start from scratch, and let the citizens of this city have a voice in what [the Met] should be like in the 21st century, not the trustees.“I played park ball all my life,” Nicholson continues, while sitting in her spotless white living room with a couple of champagne bottles in a bucket and a large LeRoy Neiman horse-racing scene; the noise from the Met, of crowds and buses and break-dancers, floats over at full throttle. “If you cheat, your mother and father know about it. I respond immediately to injustice. As a property owner, I felt the Met handing us something as a fait accompli was completely unacceptable. Nobody should be able to have what they want just because they want to have it. Somebody has to discipline the Met.”

The MMHDC claims to represent 600 families, but that includes everybody who lives in the nine buildings facing the Met whose boards have contributed, whether individual tenants side with the museum or the opposition. “I just think it’s wrong that a few people living on the top floors are causing this ruckus,” says Richard Walter, a fellow owner at 1016 Fifth and a supporter of the museum. “People in the back of the building don’t care.”Pat Nicholson says that about 140 contributors have actually reached into their own pockets to support the struggle. “There are eight or so families in the $10,000-to-$20,000 range, and another 25 families in the $1,000-to-$7,500 range,” she says. The average contribution is around $500.

Shauna Denkensohn, an officer of the coalition and a resident at 1025 Fifth Avenue—that’s the building with the Fifth Avenue address and impressive canopy even though it’s around the corner—insists that Pat Nicholson isn’t an army of one. “It’s a large group of concerned, active citizens,” she claims. “The Met is acting like a developer. We love art; we oppose the slashing and digging in granite. I’ve been going since I was a little girl. My mother is an artist. My son grew up thinking the Temple of Dendur is an indoor playground. “I’ve seen it go from this wonderful cultural institution,” she goes on. “You go to an exhibit, and it’s three rooms of art and two of sales. It’s become a money machine. I think somebody calls it Bloomingdale’s North.”

De Montebello heartily disagrees. “I would be surprised if even 3 percent of the space of the museum is devoted to shops,” he says, though he concedes that the museum store off the Great Hall is an important source of revenue. “It allows us to show art and maintain excellence. And everybody will tell you we are the finest art bookshop in town. So it isn’t just curios. This pietistic attitude toward merchandising is silly.”

Sam Peabody says that of the six families at 990 Fifth, where he’s president of the board, four support the coalition, one is noncommittal, and one opposes it. “She’s a widow who has promised her husband’s collection to the Met and therefore is being courted,” he confides, declining to give her name.One of the few buildings that doesn’t support the MMHDC is home to Arthur Sulzberger Sr., chairman emeritus of the New York Times and a Met trustee. However, Estelle Greer, an interior designer and the building’s president, says deference to the former Times publisher has nothing to do with the board’s position. “I don’t even discuss this with him,” she says of the contretemps, adding that her board needed little encouragement to side with the Met. “She’s a wild creature,” she says of Pat Nicholson. “I wouldn’t get involved with her. First of all, she’s extremely articulate. She loves paper and words. She can bury you in paper. But she doesn’t know what she’s talking about. She’s on this cause. It’s obviously psychologically doing something for her.”Greer isn’t alone in feeling that way. When the Met came before Community Board 8 a few weeks ago to unveil its plans for the Roman court, Pat Nicholson, the only member of the coalition present, asked so many questions that Chuck Warren, the board’s president, eventually silenced her. “They wanted us to come out and say what the Met is doing is bad,” Warren says. “I don’t think the board necessarily feels that way about this project.”To the Met’s opponents, the community board, like the Parks Department, is nothing more than a rubber stamp for the Met’s empire-building ambitions. “The community board gave Pat an incredibly hard time,” says Edwin Bobrow, former president of 1025 Fifth’s co-op board. “She was polite but forceful with our position. As soon as she rose to speak, they’d want to shut her up.” Nicholson has even acquired the home phone numbers, some of them unlisted, of many of the members of the Met’s board, a batting order that includes, in addition to Kissinger and Sulzberger, developer Bruce Ratner, investment banker Steve Rattner, and socialite Annette de la Renta.“You ask people whoever can give me addresses and phone numbers,” Nicholson explains. “You’d be surprised what you get back—‘I met them here’ and ‘So-and-so knows this one.’ ” She adds that she resists the temptation to pick up the phone and plead the coalition’s case, mailing them her organization’s literature instead. “Most of these people would have gotten these things by fax,” she says, adding that she hasn’t received any response. “I don’t feel we should intrude on their lives.”The Met’s board has been noticeably silent throughout the unpleasantness. Calls to board members, including board chairman James R. Houghton, of the Corning Glass family, weren’t returned, though Harold Holzer, the museum’s vice-president for communications, knows of the attempts to reach them within minutes. De Montebello says he’s discussed the matter with the board, but that’s all he’ll say. “The answer is obviously yes. You know that. We’re a serious institution.”The Met’s propaganda machine is hardly less active than the coalition’s. The museum appears to have a rather well-developed network of spies who live in the buildings across the street and forward everything from Nicholson’s fund-raising appeals to tenant lists. “We get phone calls and letters: ‘Right on!’ ‘Go for it!,’ ” says David McKinney. “We believe a vast majority of our neighbors are supporters of the Met.”Sam Peabody says he recently buttonholed a Met trustee, an old boarding-school classmate he encountered at a party. The results were decidedly mixed. “He was, well, quite evasive.”A Met trustee, who asked to remain anonymous—“The Met, i.e., Philippe, gets very sensitive. [They say,] ‘You should just refer them to us,’ ” he confides—admits he has trouble feeling the coalition’s pain, especially since he doesn’t live on Fifth Avenue himself. “One or two people I know across the street—they protest to me. Naturally, one doesn’t like to hear noise. But, good grief—we’re living in Manhattan. As a matter of fact, we hear all the ambulances going by to Lenox Hill and the police cars running home to get dinner.”Hoving, whose self-confidence seems only to have grown with the years, says, “In a decade, the museum will bless Pat.”One might have thought that Peabody and his fellow members of the MMHDC would be feeling somewhat humbled at the moment. On May 14, they went down in defeat when a State Supreme Court judge dismissed, on a technicality, their case challenging the Met’s plans. The judge, Marcy S. Friedman, ruled that the statute of limitations had run out on filing a lawsuit.However, they are appealing—the MMHDC expects a ruling on the appeal in the fall and a decision by the end of the year—and are hopeful that if they win their appeal (they’re arguing that the clock on the case should have started running later), Judge Friedman will rule in their favor the second time around. Friedman, in her decision, acknowledged that the MMHDC had raised “a serious issue” about the environmental-review process, which occurred when the Parks Department okayed the museum’s 2000 master plan.Nicholson claims that if the coalition wins its appeal, the Met may be forced to halt its plan for the new Roman gallery, the Leon Levy and Shelby White Roman Court (a crane will be assembled inside the museum in the next few weeks).An April 2004 stipulation, in Judge Friedman’s court, effectively gives the coalition much of what it’s been fighting for. The Met agreed to cancel the removal of the fountains and the excavation. The Met plays down the stipulation. “We affirmed that we weren’t going to do what we weren’t going to do,” says Met outside counsel Michael Gerrard—it had canceled the plan for the fountains in 2002. “By the way,” adds David McKinney, “we also stipulated we wouldn’t do any blasting. We’d also stipulated we wouldn’t do weapons of mass destruction.” The stipulation leaves ambiguity as to whether the Met may take up its plans in the future, and it hardly seems to have appeased the coalition, which has vowed to press on. While the most obvious explanation for why it’s doing so is that it can—it collected $500,000 to wage the first phase of its campaign—the neighbors also seem to believe that De Montebello won’t be stopped until they put a silver bullet through him. “They’ve canceled their plans, for who knows how long,” Peabody says. “We also wanted a stronger statement from the courts.”David McKinney admits the Met might have been more sensitive in the way it rolled out De Montebello’s master plan. “I think we have become much more communicative with the community board in the immediate neighborhood,” he says. “We’ve made lots of changes related to traffic. We’re much more sensitive to after-hours work, to noise, the roof.”It’s hard not to speculate that Hoving’s disagreement with De Montebello over his expansion plan is a symptom of an Oedipal conflict. De Montebello, after all, was brought in with a mission of calming the chaos created by his mentor. By remaking the museum, he’s erasing Hoving’s legacy, staking his own claim to be the museum’s most important director. There are many who agree with him. While acknowledging that Thomas Hoving did fine things for the Met, Ashton Hawkins, the Met’s executive vice-president and chief counsel who served under both men, believes De Montebello to be the superior director. “He believed in and built up the curatorial staff, and always considered it the strongest part of the museum,” Hawkins says. “Philippe works much more by consensus and careful planning. That makes him a more effective leader.”However, others say that it’s precisely De Montebello’s curatorial disposition that denies the museum the brilliance it achieved under Hoving. “He’s basically a curator as director,” says Jay Cantor, an art historian who cut his teeth working with Hoving. “Philippe has done a wonderful job sprucing up the museum’s gallery installations and expanding available exhibition space. He is a traditionalist, with deep roots in connoisseurship. As exhibition opportunities diminish because of difficulties securing loans, a more imaginative approach, as well as better ways of engaging the public and the insights of museum professionals, may be in order. “In some ways, the Metropolitan Museum and the Metropolitan Opera are similar,” Cantor continues. “They are both major cultural institutions that bring enormous resources into the presentation of a largely traditional repertoire.” Pat Nicholson recently sent out a new fund-raising letter to pay for the coalition’s appeal. The suggested contribution is $2,000 for families whose apartments face the park, $500 for those who don’t, and $1,000 for townhouse owners around the corner. “If we even have to advance money and have to get people to support it on the backside, that’s what we’ll have to do,” she vows.Meanwhile, a tense truce prevails on Fifth Avenue. Shauna Denkensohn says she still visits the Met, but not as frequently as she once did. And she refuses to pay, much to the chagrin of the hapless museum cashiers. “They said, ‘There’s a fee,’ ” she recalls of one visit. “I said, ‘No there isn’t. Call the manager.’ The supervisor didn’t even know. I said, ‘If you want me to go home, I have a copy of the lease from the 1880s.’ I know other people who have had the exact same problem. I was going in for Friday-night cocktails and music.”Nicholson no longer sets foot in the museum. “We used to be sustaining members,” she says. “I used to go over and have brunch. It’s a terrific deal. They have a great weekend brunch. But I gave up my membership.”