The last time I saw Margaret Trigg, I ducked into the doorway of a 14th Street bodega to avoid her. But I don’t think she would have noticed me anyway—her walk was manically purposeful. Her face had the overly smooth, waxy sheen of too many plastic surgeries, and her legs, moving quickly through the summer crowds of Chelsea, were bone thin. Clearly, she was on her way to something of importance. But wherever it was, I certainly didn’t want to go there. A regular in the downtown stand-up scene and an avid writer and performer of one-woman shows, Margaret would call to invite me to watch her acts or to pitch stories about her to local magazines. Like so many small-town beauty-queen types, she’d moved to New York to become an edgier version of Katharine Hepburn. At one time, Margaret had been well on her way. She was funny, talented, and beautiful, so much so that ABC saw fit to cast her as the lead in a sitcom.

But Margaret was a construction, and like most constructions, especially those built with the peculiarly toxic material of ambition and self-loathing, she was eventually bound to collapse.

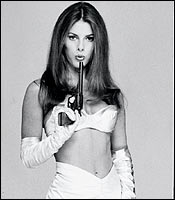

I met her in 1992; the East Village still had a grubbiness then, enough of an atmosphere to keep Texas farm girls tucked safely away on the Upper East Side. But Margaret had a sense of wonder about downtown, where she performed her stand-up comedy act at a variety of venues, many of them heavy on mildew and light on charm. She, however, had a radiance about her that made the audience forget about the uncomfortable seating and odors. She was gorgeous, with a caramel-colored mane and the face of a forties pinup girl, almost too beautiful for anyone to pay attention to what was coming out of her mouth. She wore long spaghetti-strap gowns designed to hide her rather voluptuous figure, and ranted onstage like a screen goddess gone mad. She wrote her comedy pieces from a small, hopelessly dusty two-room apartment on Thompson Street filled with a combination of looming, dark antiques and showgirl kitsch. It was not unusual to see a fuchsia feather boa draped over a rump-sprung Queen Anne chair, a combination of Edward Gorey and a Las Vegas bordello. Few would have guessed that she was a rancher’s daughter from Bastrop, Texas (population: 6,200).

Even as a teenager, Margaret was focused on moving to New York to become a star, drawing her inspiration from the pages of fashion magazines, which she channeled in her one-woman show Growing Up Vogue. “She was always a performer, from the time she was a little bitty thing,” says her mother, Minifred Trigg. “I’d give her my old cocktail dresses, and she’d dress up and make up plays. She became a majorette in high school and insisted on the fanciest outfits with the most trim.” Margaret also pushed the Bastrop envelope in public, forcing her cousin to try on debutante dresses with no underwear to scandalize her very proper southern grandmother. Her exploits at the local Wal-Mart were equally eccentric: She’d go there with a camera and chide the clerks into giving her their smocks and taking pictures of her in provocative poses. “She knew there was a more exciting world out there,” says Margaret’s niece, Susie Trigg, who was a surrogate little sister.

“Bastrop is a little town—it almost seems like it’s got a bubble over it. Margaret wanted something much bigger from her life.” Margaret always had unfailing drive. Before moving to New York in 1989, she had already starred in a low-budget science-fiction film, R.O.T.O.R., in which she was tormented by a homicidal robot. It was closer to Plan 9 From Outer Space than 2001, but it offered a glimpse of the actress she would become. When she performed, “she was able to completely transform herself,” says Francis Hall, also known as Faceboy, who recently hosted his 500th open-mike night at Collective: Unconscious, a Lower East Side alternative theater. “If she was doing a teenage-boy character, for example, you’d completely forget it was Margaret.”

Once in New York, Margaret entered the comedy world in a series called “No Shame,” which found a home at Here Arts Center, a performance space in Soho whose alumni include John Leguizamo and The Practice’s Camryn Manheim. “Her pieces were hilarious, but they were also commentary on societal mores and traditions,” says Robert Prichard, who met Margaret through “No Shame” and founded another venue where she frequently performed. “I was not just looking for comics, but real performance artists, and Margaret was it. She was sort of a female Lenny Bruce.”

Rather than do stand-up in the Jerry Seinfeld tradition, Margaret expressed her comedy in a series of sharply drawn characters, each with an ax to grind. There was a narcissistic shoe model, a self-absorbed acting teacher, an elderly southern lady, and a burned-out teenager, to name a few. “She used them to express her outrage at society’s demand that women look a certain way, and the southern social mores that demanded women act a certain way,” says Prichard. She wrote all of her own material, poking fun at the ridiculous behavior she believed evolved from conformity. “She and I used to brainstorm crazy comedy ideas,” says Steve Bird, a writer and longtime friend of Margaret’s. “One time, she was obsessed with the expression ‘Are we on the same page?’ ” It was clear to everyone who knew her that she was talented and had the goods to go far in the entertainment world.

But the one thing that got in her way at that time, at least in her mind, was her figure. “She’d seen enough episodes of Friends to realize that women with serious back were hardly taken seriously in Hollywood. That’s when the laxative abuse began,” says Pete Holmberg, a comic turned public-relations executive. “She loved to eat, and it was a way she could literally have her cake and eat it, too.”

Though she was never really overweight, “she was teased about having a big butt in high school, and her looks were really important to her,” says her niece Susie. “Every time she came home from New York, she’d ask me to take her picture in one of her outfits. She’d say, ‘I’m not going to look like this forever.’ She was deathly afraid of becoming old, being fat, and losing her beauty.” Her mother agrees: “Someone said something to her about her weight in high school, and she just never got over it.”

Her family simply assumed that getting thin was part of living in New York, where seemingly everyone was. “She’d come home to Texas, and we’d all see the laxatives in her suitcase,” Susie recalls. “We assumed she was using them for their original purpose. But I know people were thinking, How did she get so thin?” And Margaret liked it that way: It was hugely important to her that people think she was on the verge of fame, particularly the people back home. “I always got the impression,” Holmberg says thoughtfully, “that she desperately needed to be better-looking than other women, that she never got over not being the prettiest girl in school and was going to spend the rest of her life proving everyone wrong through being thin, beautiful, and famous.”

Once she began this self-punishing regime, Margaret slimmed down quickly. She started buying microminis and stacked-heel boots, teetering around the city bare-legged. It was hard for even the most cynical Lower East Side denizen not to notice this stunning girl clad in outfits usually reserved for go-go dancers and drag queens. And the thinner she got, the tinier her outfits became. All practicality was tossed aside so she could experience the rush of getting attention on the street. “It would be wintertime, and Margaret would walk around with practically nothing on,” says Jennifer Flynn, a friend, neighbor, and fellow performer. “I don’t know how she did it.”

In the mid-nineties, she was signed by the Gersh Agency, a talent agency specializing in comedians. Gersh got her a small gig playing a hooker on Homicide: Life on the Street. That led to her winning the role on ABC’s Aliens in the Family of Cookie Brody, an alien mother with a brood of multicolored children who weds an earthling. She was also offered a spot in an ensemble cast on comedian Dana Carvey’s show, but Cookie was a starring role, and the part paid almost twice as much. Initially, Margaret was hesitant—some of her fellow players were oversize puppets, and she’d have to trade in her pinup-girl aesthetic for a funky foam headdress. “She hated the costume, and she hated the fact that she had to play a mother,” says Holmberg. “She didn’t think it was glamorous. She really wanted to be an ingenue.” However, she rose to the occasion. The show was hardly an Emmy contender, but if you watched Margaret, the way she sashayed so confidently through the fake living room, it was hard to believe that the neon-colored behemoth marionettes were not her kids. She was so natural that no one could imagine how ambivalent she was about this first shot at stardom.

Ambivalence aside, she tried to share her newfound wealth with those still struggling. “One of the best things about Margaret was that she didn’t just ditch her friends who were still trying to make it,” says Prichard. “She’d take her industry friends to downtown comedy shows in the hopes the performers would be discovered.” Others don’t remember her television days so fondly. “I always loved Margaret, but she was so competitive, she never let you forget that she had deals going down. It was as if she were saying, ‘I’m better than you,’ ” says Steve Bird. Her stint as a Hollywood comer, however, was short. Aliens tanked after a few episodes, and instead of looking for another TV role that would suit her, at 32, she kept going after parts for much younger women. “There were so many roles she could have had easily—in soaps and sitcoms—but she just didn’t want those older parts,” says Holmberg.

Aliens was the last real job she ever had. “Margaret just had to be the pretty young thing. She got increasingly stubborn and wouldn’t take direction. Even when she was auditioning for a part as a well-known character on a soap, she refused to take any criticism or even watch a tape to see how the character had been played,” Holmberg adds.

“Someone said something to her about her weight in high school, and she just never got over it,” says her mother. Her family simply assumed that getting thin was part of living in New York, where seemingly everyone was.

And it was then that her real obsession with plastic surgery began.

She wasn’t a complete cosmetic-surgery neophyte: She’d had a nose job when she was in high school. But her work for Aliens had earned her about $120,000, which she started spending on ways to alter her appearance.

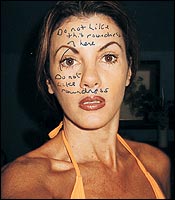

After the show ended, she decided to have a second nose job, and then she decided to have her eyes done. Then came her eyebrows and liposuction on her hips and thighs. “I question the ethics of the surgeons who operated on her,” says longtime friend Danielle Fenton. “She had her nose done a third time, several eye jobs. She told me that the last surgeon she visited wouldn’t touch her nose. But she always got some surgeon to do her bidding.” There was also a period when her eyebrows seemed to have risen an inch up her face, the probable result of at least one, if not more, brow-lifts. The surgeries became increasingly bizarre. “She was wearing a lot of weird makeup to camouflage scarring from too many eye jobs, and her nose was really weird-looking,” Fenton says. Margaret even went so far as to take one of her head shots, trace her face on it, and mark it up with comments about how her nose needed to be a centimeter smaller or her eyebrows were a few millimeters too arched, and filled notebooks with childish drawings and notes. “Little fat in lips,” says one. “I don’t want a deep or hollow eye crease. I hate this about upper-lid jobs.” Weeks before her death, she was planning yet another procedure with Dr. Lawrence Reed, of the Reed Center in Manhattan (Reed would not comment). If she could just make herself perfect, it seemed, then she would get the break she so deserved and longed for.

Holmberg and other friends were astonished. “I don’t know what freaked me out more, the fact that she thought she needed surgery or that the surgeons were willing to operate on someone who obviously didn’t need it and was clearly very messed up and fragile at the time,” he says.

Fenton believes that although Margaret was indeed scared to death of growing old, the surgeries served another, stranger purpose. “Margaret was obsessed with balance and composition,” says Fenton. This was certainly true of her wardrobe and apartment—she designed many of her own clothes to her specifications, and her furniture was carefully chosen and placed just so. “Plastic surgery allowed her to design her face.”

Her seeming imperfections didn’t stop her ambition. After Aliens, she was as determined as ever, churning out half-formed star vehicles for herself in notebooks and on typewriters. In “Half Hour Pilot,” she plays herself, wearing “fabulous, sexy outfits” in a show that deals with sex “in a balls-out, absurd, comical, funky way.” In “Carson and Griffin,” an X-Files meets Austin Powers sci-fi sitcom, she casts herself as a “beautiful martial-arts expert with a genius IQ and a problem with authority.” “City Girls,” which Margaret called Ab Fab meets Romy and Michele, had her cast as Maggie, an aspiring fashion designer who everyone thinks is half-crazy.

None of these dream projects materialized, and Margaret was not exactly the office-temp type, so when money was tight, she read tarot cards in strip clubs such as Stringfellows and Scores. The skin industry seemed to have a strange draw for her: Margaret adored the tiny outfits and the attention from men. Even though she was in her mid-thirties—almost old enough to have given birth to some of the strippers, “it gave her constant reinforcement that she was still young and gorgeous,” says Susie. “Some of the strippers were teenagers, but Margaret could still get as much attention as they could, and she loved it,” says Holmberg. Margaret’s mother thinks that these jobs played a role in her demise, particularly when it came to her eating disorder, which she maintained while pursuing her surgical makeover. Few industries are as notoriously brutal on women as the sex industry, where a paycheck depends solely on how well one titillates customers. “She made so much money in those places. There was such an emphasis on being young and beautiful. Of course, she thought that that was the most important thing, and it may have made her eating disorder worse.”

While she was great at getting male attention, however, she was not great at keeping it. “All of her relationships followed the same pattern,” says Holmberg. “She’d meet a guy, become completely obsessed with him, he’d dump her in two weeks, and she’d twist herself into knots wondering what went wrong.”

Dave Juskow, a comic turned writer, has firsthand knowledge. He and Margaret were together in the mid-nineties. “I saw her at a taping of Caroline’s Comedy Hour. She was wearing this red dress and had this big sexy J.Lo ass. She was the most gorgeous girl I’d ever seen.”

So enamored was Juskow that he brought her to his family’s Passover Seder. “I should have known better. She had trouble in situations that required decorum. She wore this crazy long dress and formal gloves and stuck her breasts in my father’s face. She was such a diva,” he remembers, laughing. “Her behavior in the bedroom was even wackier. She’d dress up in a Catholic-schoolgirl costume and ask me to pretend I was her uncle. Then she’d say, ‘Uncle David, I can’t sleep. Will you put me to bed?’ Then when I said yes, she’d call me a pervert and give me the finger.”

Ultimately, the two split, says Juskow, “because you couldn’t have a conversation with her. It was all about her, how she could succeed in the industry, how she looked. After we broke up, I’d see her prowling around my street, and I just know she made dozens of phony phone calls to me.”

But the big unrequited love of her life was actor Justin Theroux, who co-starred with Trigg in an indie film called Dream House. “Margaret believed that Justin was her male counterpart,” says Holmberg. “She thought he had the same in-your-face sensibility. One night, she and I went to the bar where he worked, and all she could do was ask if she looked good and whether or not he was looking at her, if he was into her. But she never got him to have sex with her.”

“She started fabricating projects so people would think she was working. She’d say she was doing a movie with an actor who’d been out of the spotlight. For a while, it was Julian Sands.”

Holmberg pauses. “She scared the hell out of men. As smart as she was, she had a very adolescent sense of what a love relationship should be like. She honestly thought that dressing in tiny outfits was what attracted men and what got you ahead.”

For several years, Margaret’s life followed a pattern: She wrote and produced her shows, she worked at Scores, and slowly, still using laxatives, she continued to starve herself. Her behavior, once delightfully wacky if a bit off-kilter, became strange and shrill. “The fact that she was getting sick was so apparent in her work,” says Prichard. “I’ve watched tapes of her shows. Toward the end, she just rambled manically. It was like watching her brain unravel.” She lost all of her theatrical representation, through bad behavior or bad luck. First she was fired from Gersh, and then went through a series of dubious talent agents, many of whom asked for sex in return for representation. “She even started fabricating projects so people would think she was still working,” says Holmberg. “She’d say she was doing a movie with an actor who’d been out of the spotlight for years. For a while, it was Julian Sands.”

But April of 2002 marked the beginning of her first serious downward spiral. She’d damaged her rectum from the laxative abuse, and her doctor told her she had to stop. She called friends, hysterical. “I can shit into a bag when I’m 72, not when I’m 37,” she howled tearfully, according to Holmberg.

In May of the same year, she returned home to Bastrop to kick a sleeping-pill-and-Xanax habit. Her friends and family were shocked: Margaret had always been scrupulous about staying away from drugs—she didn’t even drink.

“Margaret stepped off the plane and was just bones, just this frail little body in a minidress,” Susie remembers wistfully. Minifred took her to two Texas psychiatrists, both of whom diagnosed her as bipolar; a third, back in New York, would say she had borderline personality disorder.

“At first, she romanticized the diagnosis,” says Susie. “She said that all these famous actresses were bipolar, and it was just a normal thing for an actress to be.” But the family questioned whether that was a correct diagnosis. The doctors prescribed all sorts of pills: Geodon, an antipsychotic; lithium, for bipolar disorder; bupropion, for depression. Then Margaret began pursuing her own diagnoses. She was sure she had adult attention-deficit disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. On top of all of the prescription drugs, she was taking herbal diet remedies and abusing laxatives. “She made sure she did plenty of research so that none of the drugs were ones that caused weight gain,” Minifred says. “But she seemed to think there was some kind of magic pill she could take and everything would be all right.”

After about a month, she returned to New York, but a few weeks later, in the summer, she wound up in the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital. Minifred says, “She was walking home from Scores with a friend, and she started scratching herself and yelling that the drugs she was taking were making her feel awful. The friend realized that she needed help and asked Margaret if she wanted to go to Bellevue, and she said yes.”

Thus began a campaign of phone calls begging friends to convince her doctors—and her mother—that there was nothing wrong with her. “Please call the doctors and tell them I’m fine,” she pleaded. “I don’t have any psychological problems. I just need to stay thin.” According to Minifred, it was during her stay in Bellevue that Margaret found her miracle pill, Adderall, a highly addictive amphetamine traditionally prescribed for attention-deficit disorder. Her appetite plummeted, and it kept her awake during those long nights at the strip clubs. However, though Margaret received many diagnoses, she rarely stuck with one doctor’s treatment plan, and aside from her continuing eating disorder, her true diagnosis remained unclear.

But even with her so-called magic pill, “she succumbed to what she fought against—the global corporate concept that all women have to be thin and perfect,” says Hall. The laxative abuse had gotten so bad, according to friends, that Margaret lost control over her bowels. “I’d get phone calls from her telling me that she’d had an accident in the dressing room of Victoria’s Secret,” Holmberg says. “When I cleaned out her apartment, I found dozens of pairs of boys’ socks. She never wore socks. She was carrying them around so she could stow her accidents in them.” She had also lined her apartment with towels. If she didn’t make it to the bathroom, she would go on the towels and throw them out the window onto Thompson Street.

“I saw several soiled towels that I knew were Margaret’s on the sidewalk,” says Jennifer Flynn. Toward the end, the thing she obsessed over and cherished most—her youthful good looks—disintegrated. Her hair started falling out, so she began wearing wigs. Her hands had the shriveled, cracked look of an old woman’s. And she was achingly thin. “She looked like she’d aged twenty years,” says Juskow. And her appearance wasn’t the only thing that was deteriorating rapidly. “She came to my house a few months before her death and was yelling, threatening that she could beat me up and throwing stuff around,” Juskow adds. “I had to threaten to call the police to get her to leave.” She also began talking about suicide, leaving long, frightening messages on friends’ answering machines. “She went so far as to say who she wanted to do the makeup on her corpse and where to find the dress she wanted to wear,” says Holmberg. “But it always came back to her looks. One night she called me, completely hysterical, so I walked her around Washington Square Park to calm her down. All she could talk about was getting money for her next eye job.”

Even Susie, one of her closest confidantes, found her impossible. “She’d call me and beg me to get her mother to give her money,” says Susie. “She was fired from Scores. She thought that if her mother just set her up, bought her a dress shop or some business to run, everything would resolve itself. She was terrified because she said she had no real work experience.” At one point, she was calling Minifred 50 times a day, begging her to set her up financially.

It almost seemed like she was going into retirement, as if she were a wizened Miss America trying to hang up a tiara she’d never had.

On October 16, 2003, Margaret called 911—she had an itchy rash and couldn’t handle it. The paramedics took one look at the state she was in and brought her directly to Bellevue. Initially, the therapy there seemed to be helping her heal. She told friends she was president of the patients’ association, and she was eating and gaining weight. “On the day she died, she called and asked me to bring her doughnuts and other treats,” says Danielle Fenton. “During our visit, she gobbled up the food in her funky pajamas and wacky makeup—she was made up, even though she was in Bellevue. She seemed lucid to me, better than I’d seen her in a long time.”

But even Margaret seemed to sense that this was the calm before the storm. “I’m going to die in here,” she said breathlessly on Fenton’s answering machine. On November 16, 2003, she was found dead in her hospital bed. According to autopsy reports, her official cause of death was a heart attack resulting from prolonged amphetamine abuse. Bellevue will not comment on her death.

Though some in Margaret’s world were surprised, others saw it as an inevitable end to years of agony. Margaret Trigg was the New York cliché—the country girl who comes to the city to make it big—gone horribly wrong. Ambition is usually romanticized. In her case, it was a fatal disease.

On December 7, 2003, dozens gathered at Collective: Unconscious for a memorial service honoring Margaret. Those close to her spoke of her talent, wit, and spirit. And on girlbomb.com, a Website celebrating alternative art and performance, there are more than 100 postings, some sweet (“You were so valiant. Sometimes the tiniest stumble can be fatal. What happened?”), some bittersweet (“Damn it, Trigg. I was just starting to like you”), some wishing Margaret happiness in the next world. “Shortly after her death, I had a dream about Margaret, a dream that felt incredibly real. We were on 14th Street, and I told her I felt bad about what had happened between us,” says Juskow. “But she told me everything was okay. She said, ‘I like it here. I’m young and beautiful.’ ”