Although not the type to look backward, Pierre Boulez may actually be getting a bit wistful as he nears 80. Or perhaps it’s just me. Having closely followed Boulez’s career over the years, I came away from his recent concerts in Carnegie Hall with the Cleveland Orchestra feeling positively nostalgic. It was back in 1965 with the Clevelanders that Boulez made his impressive American debut as a conductor, surprising many of us who had, up to then, thought of him only as an influential avant-garde composer—and a forbidding, slightly arrogant young firebrand at that. Having established his credentials as an important conductor, Boulez then went on to astonish us further by taking on Wagner‘s Parsifal at the Bayreuth Festival, cementing ties with the global music Establishment that he had once scorned.

Now, nearly 40 years on, Boulez was back conducting the Cleveland Orchestra and making Act Two of Parsifal the main order of business, a preview of his return visit to Bayreuth this summer. If all this put Boulez in a sentimental mood, he didn’t show it—he made Wagner’s final opera sound excessively crisp and chillingly objective. This Parsifal is worlds away from James Levine’s leisurely Wagnerian romance at the Met, let alone Hans Knappertsbusch’s spacious, visionary interpretations in Bayreuth during the fifties. In fact, Boulez’s efficient approach has become so demystified and briskly paced that the soloists (Michelle DeYoung, Thomas Moser, and Eike Wilm Schulte) had virtually no opportunity to explore the expressive potential of their roles. All in all, a big disappointment.

The first Cleveland program was a more satisfying Boulez musical offering, even if the new piece by Marc-André Dalbavie seemed less than compelling. Its title, Concertate il Suono, alludes to a spatial component that pits four small instrumental ensembles located in various parts of the hall against the full orchestra. This is not exactly new—Henry Brant has been doing the same sort of thing for decades, and with a good deal more panache—and even in this meticulous performance the music sounded rather spongy. There was more zest in the two collaborations with Mitsuko Uchida, a pianist who can more than match Boulez in terms of musical intelligence and fastidious precision. Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G and Messiaen’s Oiseaux Exotiques found everyone involved in top form, as did Bartók’s Miraculous Mandarin, a Boulez specialty that never seems to lose its fizz and dangerous edge.

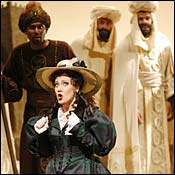

The Metropolitan Opera’s revival of Rossini’s L’Italiana in Algeri is one of those cheerful occasions made all the more merry because the ingredients did not necessarily guarantee success. For whatever reason, James Levine has never shown much affinity for Rossini and the bel canto repertory. When he does conduct these pieces, his lack of interest is almost palpable, but not this time—the score sings and dances in all the right ways, and every one of the composer’s instrumental felicities is savored with real affection.

The other big question mark was Olga Borodina, whose vocal and physical glamour is real but not the sort one associates with the technical bravura and pinpoint articulation needed for one of Rossini’s resourceful mezzo minxes. The fact that her vocal equipment does indeed extend so far is more than proved by this ravishingly sung interpretation, an adorable Isabella who can also find more witty ways to wave a fan than Bea Lillie. By now, it should come as no surprise that Juan Diego Flórez is the ideal Rossini tenor, combining youthful charm with florid razzle-dazzle, or that Ferruccio Furlanetto (Mustafà) and Earle Patriarco are masters of the buffo idiom. Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s aging production looks a bit drab, but this cast would be worth seeing even in street clothes.