They looked like any other hot band come to town with a hit record, filling Roseland, a thousand kids bashing their brains out to the beat. Except Taking Back Sunday, on tour around the country, and Europe too, weren’t just passing through. They were home, as close to home as Long Island is to Manhattan, a distance of debatable dimension, at least psychically.

In case there was any doubt as to Taking Back Sunday’s origins, one guy to the left of the stage, attired in the band’s standard IF WE GO DOWN, WE GO DOWN TOGETHER T-shirt, kept shouting “Amity! Amity … Amity football!!!” Through the din, Eddie Reyes, TBS’s founder and guitarist, who spent a number of seasons toiling as an undersize placekicker on the Amityville High football team, acknowledged the tribute. “Amity,” Eddie said, pointing his finger toward the screamer, a stumpy sort (not unlike Reyes himself) who looked heavenward, hands raised in thankful answered prayer.

As far as Reyes was concerned, the feeling was mutual. The Roseland gig represented something “totally awesome … a full circle.” So many nights he’d come into the city, on the LIRR or in a beater car, to clubs like the Continental, Coney Island High, and good ol’ CBGB to see metal and hardcore bands. Someday, Eddie thought, pushing toward the stage, thinking about being up there himself. Now the time had come, a hundred times bigger than Eddie had imagined, with Taking Back Sunday’s new disc, Where You Want to Be—which debuted in July on the Billboard chart at No. 3—about to go gold, like the group’s 2002 effort, Tell All Your Friends.Plus, it was his birthday, his 32nd, a grandpa age for a punk rocker, but one that imparts a Yoda-like air of authority to the impish musician. “I’m old enough to appreciate everything but not old enough to be dead,” Eddie says cheerfully, noting that it was an excellent time to be “a garage guitar player from Long Island.”

No doubt about it. Humble, maddening, subdivided Lawn Guyland, the nowhere zone between the Queens line and Puffy’s “White Party,” is generating plenty kar-rang-ish heat these days. Taking Back Sunday (the name comes, Reyes says, from “an act of will, because Sunday’s when you should hang with your family and friends … like the Bible says, a day to kick back”) and its sometime blood rival from Levittown, Brand New, are at the top of the heap. Brand New’s rousingly elegiac Deja Entendu has also sold upwards of 500,000 copies, and their success, along with bands like From Autumn to Ashes, As Tall As Lions, and Straylight Run, has sent A&R types combing the thickly malled landscape for the next kind-of-big thing. Along with “Orange County hardcore,” “Detroit techno,” and “St. Louis alt-country,” “Long Island emo” (or “emotional” rock, which the All Music Guide defines as “confessional” hardcore, which translates into, says one fan, “really loud music by guys from the suburbs feeling sensitive and/or sorry for themselves”) has joined the pantheon of phrases used to sell music these days.

Indeed, there has been much talk in the music magazines that Long Island, where beaches are named for Robert Moses and shopping centers for Walt Whitman, is “the New Seattle.” This refers to the nineties rock epoch during which that caffeine-besotted burg produced Nirvana and hundreds of other flannel-shirt-flapping punkers—a scene that, when it comes to scenes, remains the grail.

Several weeks before the Roseland show, cruising old Amityville haunts in his slightly trashed Chevrolet Cavalier, Eddie Reyes expressed ambivalence when it came to correlating Long Island emo with Seattle grunge. After a decade of listening to such emo precursors as Fugazi, and having a hand in writing many of what he calls Taking Back Sunday’s “melodic hardcore relationship-based” songs (e.g., “The Blue Channel”: “Regardless if my pictures / They don’t line your mirror / Regardless, you know what / I’ll still wait for your call”), Eddie said, “If I hear the word emo anymore, I’m throwing up. ’Cuz it’s getting old, this idea of these guys with tattoos”—Eddie has ten at most recent count, including twin “full sleeves” and a new stalking panther. “Hugging like a men’s group, whining ‘Hold me.’ It isn’t that we’re not caring … we’re caring. Just not that caring.”

“That’s what thisscene is:findingsomething to connect to out here,where it’shard toconnect.”

We were on an L.I. rock Baedeker. On Merrick Road we stopped at Blue T Pizza, where Eddie and his buds hung out waiting for the tourists to ask The Question: “Hey, where’s the Horror House?”

“Two bucks,” his friends would say, before pointing the way. Eddie bought one of his first guitars with the money. So, “you could say I owe my career to The Amityville Horror.”

Every other block, Eddie stopped the car in front of a ranch house, backyard, or garage where he practiced when he played in his “kid bands”—Mind Over Matter, Clockwise, the Inside, and the much-missed the Movielife. This was the way it was out here, Eddie said, as we passed a tract house with an old man in a golf shirt riding back and forth on his lawn mower, seemingly oblivious, or inured, to the punk racket blaring from the double-car garage. There were hundreds of bands here, sometimes two or three on a block. Most would never make a record or even get out of the garage. But they were players, just the same.

No knock on Seattle, said Eddie (who credits Nirvana with “getting rid of the eighties haircut bands”), but that was the difference between Long Island rock and everywhere else. A place like Seattle—it came out of nowhere, blew up, faded into the Behind the Music mist.

Long Island is no such flash in the pan. Three generations of post-Elvis teenagers have come of age in this world of crumbled Dunkin’ Donut dreams. That adds up to a lot of garages, a lot of teenage angst, two things no rock scene can live without. If there’s a Mississippi Delta of garage rock, it is here, fecund spawning grounds of so many (slightly off-brand) heroes such as Lewis (later, Lou) Reed from Freeport, Pat Benatar (née Patricia Andrzejewski) from Lindenhurst, Eddie Money from Island Trees… . It goes through such disparate types as Public Enemy from Roosevelt, Gary “U.S.” Bonds of Wheatley Hills, and, of course, Billy Joel of Hicksville—once in a metal band called Attila, before a stint in the Meadowbrook Hospital mental ward.

Eddie Reyes’s family emigrated from Bogotá, Colombia, which makes him an anomaly in what is mostly a strictly white, nativist scene. But, Eddie said, “when you’re a hardcore kid, playing hardcore, going to hardcore clubs, that’s your real identity.”

Besides, Eddie added, “when I was growing up, I wasn’t a great student. I couldn’t pay attention in class. I knew a lot of people like that. Sometimes it seems like half the Island has ADD. I think it is in the water. Music, though—that always made sense to me. That’s what this scene is: finding something to connect to out here, where it’s hard to connect. It just makes it a deeper, richer thing, 360 degrees, 24/7.”

Over on Route 110, we stopped at Pete’s Deli, where Eddie sliced Boar’s Head and mixed up the chunky chicken salad for six years before Taking Back Sunday took off. Eddie is greeted at the deli like a conquering hero, but he still makes his own sandwich. It wouldn’t be cool to expect the current countermen, most of them with their own bands—deli man being the day job of choice for L.I. rockers—to slice the honey-smoked turkey for him. The scene is egalitarian like that; everyone can remember when they were nobody. Within moments, other musicians, the former singer in From Autumn to Ashes, a guitarist from All Grown Up, and assorted drummers come in, several dressed in T-shirts emblazoned with an emphatic “516.” They talk shop, slap hands, grab a couple Budweisers, disperse.

Back in the Chevy, Eddie turned on the air conditioner, the knob falling off in his hand. “If they ask me if I’m rich yet, I show them this,” he said, laughing. Recently, Eddie got married. Six hundred and fifty people showed up for the wedding in Sandusky, Ohio, his bride’s hometown. But Reyes has no plans to leave Amityville.

“This is it,” Eddie said as he stopped at a light in the middle lane of Route 110. Cars pulled up on either side, windows open, both of them blasting “Set Phasers to Stun” from Where You Want to Be. No big deal that the album wasn’t out yet, not officially, so there was every chance both listeners had illegally downloaded the tune. It is still good to hear your music in the ’hood. The light changed, and the guy to the right cut across the two left lanes and through the intersection. Amid squealing brakes and curses, Eddie watched the Toyota pull up to the bagel shop in the mini-mall across the way.

“How could I leave here?” he asked. “This is my inspiration.”

In the scene these days, it is considered hot stuff to play the Downtown in Farmingdale, the only club around with a decent sound system. “We’re the My Father’s Place of now,” says David Glicker, the Downtown’s owner, invoking the hallowed Roslyn club of the seventies. A shambling man in Birkenstocks, Glicker has been in the L.I. rock business for twenty years, originally in the employ of Phil Basile, the all-time classic Island club owner. A reputed Luchese crime-family member, Basile operated several famous L.I. clubs—the Action House, Speaks, Channel 80, Industry—three of which were the same club (on Austin Boulevard) with different names. “With Phil, I saw it all,” Glicker says with a sigh. He rates the current incarnation of Island rock as “the most exciting … because these kids, they’re making their own history. Their own art history.”

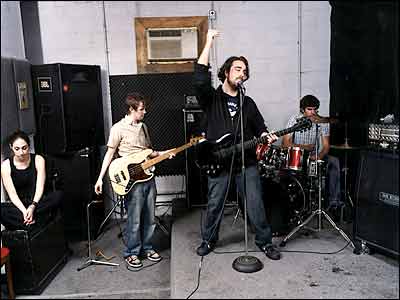

Tonight’s artists, a band called Don’t Run, is setting up for the semifinals of the Downtown’s “Rock Fight,” a battle of local bands, with the winner promised a spot on the Warped tour and a pile of free equipment from Sam Ash. Four scruffy guys in their early twenties, Don’t Run does not claim to be comprehensive when it comes to Long Island’s rock history. They don’t know the Rascals were the sixties’ Long Island No. 1, at least until they took too much acid and lost their minds, refusing to play gigs until half the bill was black. Not that they care. Says Mike Kozak, Don’t Run’s singer, “We’re just here to play.”

You can always tell the lifers, the ones who were born to rock, Long Island style. Emo guys might wear shades, but often have the look of sunless Morlocks. The beach is only a twenty-minute buzz down the Wantagh Parkway, yet there’s never been an L.I. surf band of note, probably never will be. Words like “Ritalin,” “foreclosure,” and “restraining order” come up with alarming regularity among Long Island teenagers. Of the four members of Don’t Run, three are from broken marriages. At the Rock Fight, they were up against a Locust Valley band that brought their parents to cheer like it was a soccer game. Don’t Run just shook their heads.

There’s a kind of insular austerity here. Rafer Guzmán, club correspondent for Newsday, says, “It is hard to believe, but the scene seems to be virtually drug-free.” You can’t even find a kid to bum a joint off. Teen girls line up at the Downtown in their fuzzy pink sweaters, low-slung jeans, and studded belts, but the scene is oddly asexual: The moshing and the stage diving smack more of Mary Lou Retton High School gymnastics class than groupie wantonness. Sexual segregation between performers (almost exclusively boys) and audience (girls) seems rigidly self-policed.

They’d never admit it, but bands like Don’t Run—who play songs with stark, neo-Beckettian titles like “The Absence of Temperature,” “Starting Fires in the Snow,” and “Sarcasm,” which Mike Kozak sings with a brooding, subterranean woundedness—are their own kind of bluesmen. Dem mean ol’ suburban-sprawl blues. Here are the tales of lives spent growing up ever so slightly on the wrong side of the LIRR tracks, the Munchian rage scream at the specter of diminished prospects. “Mostly, we practice and work,” says Kozak. At one point, the band was trying to get together for a group photo, but guitarist Mike Knoll, who works at Marshall’s on Levittown Road, was stuck handing out pink plastic cards indicating how many pairs of stretch pants local matrons tried on. The band had to plead with Knoll’s boss to add ten minutes to his break.

Don’t Run lost in the Rock Fight finals. Though the judges said they had played “really intense,” the winners were more “fun.” Don’t Run didn’t take the loss too hard. Winning the contest would have been cool, but they had enough equipment, so they’d just have had to sell their old stuff on eBay, which sounded like a hassle.

If emo is about “relationships,” it figures that in the tightly wrapped L.I. scene, people are going to piss each other off. Such has been the case in the typically internecine “feud” between Taking Back Sunday and Brand New, the great rivals for Island hegemony. The alleged duke-out was goosed with a recent Brand New T-shirt saying BECAUSE MICS ARE FOR SINGING, NOT SWINGING. Scenesters knew this referred to Taking Back Sunday’s singer Adam Lazzara’s signature stage gesture of faux-garroting himself with the mike cord, often executed while hanging upside down from the stage rafters like a bat and singing “You’re So Last Summer,” with TBS’s best bad-boyfriend lyric, “I’d never lie to you, unless I had to.”

Big surprise that alleged sexual perfidy is the base of the BN-TBS skirmish. The story goes like this: Seems Jesse Lacey, the Raymond Carver–loving front man and songwriter for Brand New, who once played bass in Taking Back Sunday, was best friends with John Nolan, TBS’s former guitarist and songwriter. Except then, supposedly, they went to this party and Nolan slept with (or maybe just kissed) Lacey’s girlfriend. Lacey, now in Brand New, wrote “Seventy Times 7” (the number of sins Jesus says should be forgiven): “I hope there’s ice on all the roads / And you can think of me when you forget your seat belt and again when your head goes through the windshield.” TBS’s answer song, “There’s No i in Team,” was a kind of apology (“I can’t regret, can’t you just forget it?”), but not really, mocking Lacey’s overkill hurt feelings (“Wearing your black eye like a badge of honor / soaking in sympathy”).

Things shifted, however, when Lazzara, the scene’s Über-hot boy, started dating Nolan’s sister, Michelle, to whom he was supposedly unfaithful. Outraged, Nolan left TBS to start Straylight Run. At that point, Lacey reconciled with Nolan and rekindled his dislike of TBS, allegedly bad-mouthing them at shows.

Real or not, the beef (an emo beef! OK!) has taken on a life of its own, inspiring endless Internet postings. Amid much Biblical explication of “Seventy Times 7” (Matthew 18: 21–22) is the ongoing lyrical parsing over whether TBS’s new “Slow Dance on the Inside” is “a fuck-you to Brand New” or not. TBS says this is yesterday’s papers and they’re sick of talking about it. Yet asked if he was still mad at Brand New, Lazzara grimaced and said, “No … yeah. Fuck it. Keep it going. See if I care. All I’ll say is that pride is a funny thing.”

Reyes suggested that if area code 516 was big enough for both bands, the country was, too. Still, he wasn’t thrilled that Brand New, clearly more cuddly and chick-friendly, is often regarded as the Beatles to TBS’s raunchier (second-place) Stones. Some of this was about BN’s signing with Interscope, a major, while TBS continued on the indie Victory label. That was the way of the music business, Eddie said. On the other hand, “if I hear anyone talking shit about my band, you know, it’s high school again.”

Eddie Reyes says he can see a time when he is no longer playing Long Island rock and roll. This is not an option for Peppi Marchello, something of a legend in these parts. “Once a Long Island rocker, always a Long Island rocker,” says Peppi, 60, a year past triple-bypass surgery. His head shaved, his chest still barrelly, Peppi can be found most Friday nights carrying his own equipment into joints like Rock-A-Fella’s in East Northport to play with his band, the Good Rats, before about 25 people, many so drunk and immobile as to look like what the comics used to call “an oil painting.”

It wasn’t always thus. Back in the mid-seventies, playing straight-ahead hard rock with a tasty pre-Springsteen drive, Peppi’s wild metal crooning out front, the Rats were the undisputed champs of the Island. Keith Richards once called them “the best bar band in America,” claims Peppi. “You want to know how it was,” says Peppi, who moved to Baldwin when he was 7 and then later to Nissequogue, in his clipped, knock-around tone. “You hear of the Cars? The Ramones? The Talking Heads? The Bon Jovis? They all opened for us. We began to call it ‘the curse of the Rats.’ I figured, Why don’t we open for ourselves? Then we’ll get somewhere.”

Undeterred, Peppi says, “I don’t sit around feeling sorry for myself like some schmuck living in the past.” Peppi’s sons, guitarist Gene and drummer Stefan, are now Rats. After an estimated 8,000 gigs, the band still plays every week. There are little side jobs, like selling “I. M. Happy—The Beer Guy,” a stein-holding puppet programmed to intone Peppi’s trenchant “World Party Anthem”: “Let’s have another beer / Life sucks / So hear our cheer.”

Whatever happens, says Peppi, who pronounced TBS’s Where You Want to Be “good Island music,” the thing is to keep playing. Or, as the King Rat said at Rock-A-Fella’s after jumping onto the low-slung bar, “I got five grandchildren and I’m still grabbing my balls for a living! What more could you want out of life?”

So it goes. Tonight is another kids’ show at the Downtown, and the line of 16-year-olds is down the block by 5:30. On the bill is Modern Dance, My Hotel Year, and Days Away—none of whom are from Long Island. If you want to play emo-core these days, you’ve got to hit the Island. It is “the center of the world, because you kids are so cool,” screams Pete Wentz, bassist of Fall Out Boy, a Chicago pop-punk band. A number of L.I. scenesters hold up cell phones in the manner that previous generations raised Bic lighters.

“It’s usually pretty awesome here, when it doesn’t suck,” said Patty, 17, from Huntington, as the LIRR train thundered into the adjacent Farmingdale station. Several commuters got off, frazzled from one more day in the grown-up world. Several commuters said they used to go to shows all the time. Many even played in bands. But for now, they could only cast fleeting, wistful looks, keep walking, throw their briefcases in the car, and drive home.