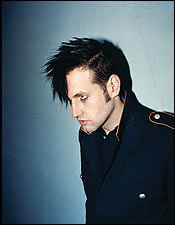

(Photo credit: Michael Schmelling)

Sam Endicott is new enough to the game of rock stardom that he doesn’t realize he should never be seen eating pizza. Killing time in the echo-chamber hallways of a Williamsburg warehouse, the lead singer of the New York band the Bravery is reduced to wiping crumbs from his Sgt. Pepper–style military coat with a flash of jet-black fingernails and knuckles across which he’s written LIONIZED. “It’s just a word I like,” he says, without looking up from his crust, “and sort of apropos of what’s been going on lately.”

But with his New Wave–y rock quintet on the verge of breakout success, Endicott has figured out a few techniques for projecting the proper front-man image. He chooses his words with deliberate intensity and does his best to temper his cockiness with an air of modesty. As he makes his way through the customary progression of bands that inspired him, from the Stones to the Ramones to the Clash, he breaks character only when he’s interrupted in the delivery of his stump speech. “There’s a whole story, dude,” he says with mild annoyance, “and I’m just on Chapter One here.”

Actually, there are two stories unfolding: On this wintry night in late January, the Bravery is opening the book on its career, with a sold-out show at Northsix just a few hours away and a self-titled debut album on Island Records coming out March 29—not bad for a group that didn’t exist two years ago. But within the larger narrative of rock and roll, the Bravery is the latest in a long line of next big things. More than that, the band is New York’s most serious bid for music dominance in a decade.

It’s not an easy time to be a next big thing—especially in New York, where the phrase conjures up smoky images of an era when every Checker cab was dropping another Blondie or Talking Heads on the doorstep of CBGB. Only two years ago, the city seemed poised for a rock renaissance, as backward-looking bands like those jean-jacketed pinup boys the Strokes and their gloomy-Gus contemporaries in Interpol came out with wildly hyped records. Yet neither band became a national phenomenon: After redundant sophomore albums, their spotlights dimmed.

But that doesn’t mean no one was paying attention to their missteps. The members of the Bravery are clearly very talented, very lucky guys, but they’re also the beneficiaries of one of the most carefully managed launch campaigns in recent history. “We try to control every aspect of the band,” Endicott says, “but not in a control-freak kind of way.” He laughs and corrects himself. “Actually, yeah, in a control-freak kind of way.”

Endicott doesn’t look like the next Joey Ramone. His sculpted facial features render him too traditionally handsome for the role—shave off his faux-hawk and he could pass for Paul Rudd. But growing up in Bethesda, Maryland, he became fixated on the Washington, D.C., area’s post-punk scene and its temperamental founding father, Ian MacKaye, of the hardcore band Fugazi. “I’d say hi to him after shows,” Endicott recalls, “and he’d be like, ‘Fuck off.’”

After graduating from Vassar in 1999, Endicott moved to New York to play bass in numerous dead-end bands. The city was stuck in a sort of Cretaceous period at the time, still faddishly obsessed with electroclash, the synth-heavy dance music more memorable for its Weimar-decadent stage shows than any actual music. Though Endicott was not a fan, these acts inspired him. “I was like, ‘These bands suck,’ ” he says. “ ‘They have no idea what they’re doing, but the idea is really cool.’ ” Motivated by their success, he was determined to manufacture his own movement, “something that celebrates synthetic sounds and modern technology but also has that visceral kick you get from seeing an honest-to-God live, organic, rock-and-roll band.”

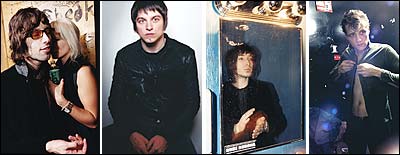

In 2003, he and keyboardist John Conway, a fellow Vassar alum, started collaborating on what would become the Bravery’s first songs, producing them piecemeal in their apartments and mixing them on an iMac. “We drew up a budget,” says Conway, 26, a Santa Barbara émigré with a Lennon-esque look and a vaguely Mancunian accent. “It was $7,000 for the whole album.”

The songs, which appear on The Bravery as they were originally recorded, sound nothing like the canonical classic rock bands that Endicott claims as influences: the Stones, the Ramones, the Clash. Instead the first single, “An Honest Mistake,” is a Frankenstein’s monster of early-eighties British rock, assembled from the rapid-fire electronic beats of New Order, the swagger of Duran Duran, and the lyrical irony of the Smiths; you can even hear echoes of the youthful, earnest Bono in the way Endicott wraps his vocal cords around a pleading line like “Don’t look at me that wa-aaaay.” As a carefully constructed patchwork of excavated body parts, it succeeds through a combination of surgical precision and brute force.

With their early recordings complete, Endicott and Conway recruited the remaining members of the Bravery that fall: drummer Anthony Burulcich, 25, and guitarist Michael Zakarin, 23, a pair of bed-headed New Yorkers, and 24-year-old Mike Hindert, a pompadoured Virginian and college pal of Zakarin’s, who was tapped to be the bass guitarist despite the fact that he’d never played the instrument before. On their joining up, Zakarin says with a shrug, “I just wanted to see what would happen.”

But nothing just happens in Endicott’s universe. “People create their own limitations,” he says. “You can do whatever you want. The thing that stops people is their own psychology.” It may be glib for a personal philosophy, but the mere fact that he has one sets him apart from his wide-eyed recruits. Although his newest bandmates are capable musicians, it’s unclear how much of a stake they have in the Bravery’s songcraft. They openly acknowledge that Endicott is the leader: They’re just happy to be riding this wave with him.

They also seem to be much younger than Endicott, although it’s hard to say exactly how much younger. Endicott claims everyone in the group is “mid-twenties,” but some public documents give his own year of birth as 1974, and others indicate he graduated from the tony Georgetown Day School in 1992, which would make him 30 or 31. An alumni officer at GDS confirmed that Endicott graduated from the school but would not say when. Endicott had contacted her several weeks earlier and requested that the school withhold that specific information. Touché.

Of course, reinventing oneself is the rock and roller’s prerogative, and Endicott’s plainly got a talent for it. In his college days at Vassar, he sported blond dreadlocks and performed in a ska collective called Skabba the Hutt, as well as El Conquistador, a band that sounded like “Joe Jackson meets the Clash meets the Go-Gos, but with dudes,” according to Jonathan Togo, who played in both groups. “Sam has always had the vision, and he puts a lot of thought into it. He looks at being in a band as its own art form.”

Through all these false starts, Endicott’s vision was evolving. By the time manager Pete Galli first heard the Bravery in October 2003, he thought they sounded like a polished, professional band. He only hoped they looked like one, too: “I was listening outside their rehearsal space, going, ‘Please don’t let there be some 400-pound dude in there.’” Almost immediately, Galli began developing a strategy to keep the band below the industry’s radar. “I told them, ‘Your songs are at ten, your recordings are at ten, the way you guys look is at ten, but you’ve never played a show, so that’s a zero,’ ” Galli says. “When you’ve got great songs and you look like those guys, there’s going to be some assistant that goes, ‘Oh, shit!’ and brings you into a label.” And Galli didn’t want his hot new act breaking too soon: “I saw them as the complete future of the next five years.”

They put together a six-month plan that would limit the Bravery to warm-up gigs at minor venues on the East Coast and culminate in a monthlong residency at a New York club. On November 25, 2003, they played their first show at Williamsburg’s Stinger Club, where a knife fight broke out in the crowd. By the time they started their showcase at Arlene’s Grocery in May 2004, the Bravery was no longer a secret.

“God bless him, but Kurt Cobain killed rock as a danceable music. ”

While they were honing their live act, they were also releasing MP3s on the popular personal-networking site MySpace.com. “When you e-mail cute girls, they want to hear good music, and they want to see cute guys doing it,” explains Hindert. The homemade files soon spread all over the Internet, ending up in regular rotation on radio stations in San Francisco, Boston, and London.

The band’s grassroots marketing wouldn’t have yielded results, though, if the Bravery hadn’t arrived on the scene at a moment when musical tastes were shifting in its direction. “Everybody was suddenly into the Cure, everybody was referencing Joy Division,” says former Arlene’s Grocery booking manager Owen Comaskey, who lined up the Bravery’s showcase. “So the timing was right, and they got it just right.”

By the third week of the residency, the shows were sold out, and Arlene’s Grocery was swarming with music-industry types—J Records chairman Clive Davis was spotted, and Interscope Records offered the Bravery a contract even before the showcase ended. The band’s dance-floor-friendly sound was a highly desirable commodity.

The dirty little secret about New York’s heralded postmillennium rock acts is that they never really sold records: Four years after its release, the Strokes’ debut, Is This It, still hasn’t moved its millionth unit, and its 2003 sequel, Room on Fire, has sold only a little more than half that; to date, neither of Interpol’s albums have even gone gold. Meanwhile, last year’s self-titled debut from the dandified Scottish quartet Franz Ferdinand has already gone platinum, as has Hot Fuss, the first record from the Las Vegas New Wave tribute act the Killers, which also scored a Grammy nomination for best rock album. “These bands are selling because they’re bringing booty-shaking back to rock,” says Galli. “God bless him, but Kurt Cobain killed rock as a danceable music.”

After fielding interest from almost every major label, the Bravery signed with Island Records just before Labor Day 2004. “The thing I think is great about this band is that while their influences are obvious, I don’t think Sam set out to do that,” says Rob Stevenson, a senior vice-president of A&R at Island. “If you ask him who his favorite bands are, he’s going to tell you the Clash and Fugazi, not the Cure and New Order. So it didn’t feel formulaic to me.”

From left, keyboardist John Conway, drummer Anthony Burulcich, lead guitarist Michael Zakarin, and bassist Mike Hindert. (Photo credit: Michael Schmelling)

In fact, Endicott will claim almost complete ignorance of the eighties bands the Bravery sounds like: “I know nothing about the Smiths,” he unconvincingly told the BBC in January. There’s no reason a rock musician should be ashamed to admit he’s a fan of the Smiths or New Order or Joy Division, so why deny the obvious influence? It’s possible that Endicott prefers to flaunt his fondness for do-it-yourself icons like the Clash—artists revered for being rock stars’ rock stars, not just avant-garde fetishes—to protect himself should the current appetite for mopey Brits prove to be a passing fad. Or perhaps he wants listeners to believe that the Bravery is blazing an entirely new retro trail, and not just encroaching on territory that competing groups like the Killers were quicker to claim. (“I don’t want them brought up in this article,” Stevenson says of the Killers, even though he’s their A&R rep as well.) It’s all part of the strategy: to look like leaders in an industry of followers.

At the Bravery’s Northsix show, a capacity crowd is already shrieking as the band launches into the opening measures of Soft Cell–style synth pop. In the nine-song, 30-minute set, every page from Morrissey’s crooning, mike-stand-caressing playbook will be revisited, until Endicott’s faux-hawk has collapsed in sweat, and Hindert has doused the first five rows with a shotgun of beer. If the popularity of a band can be measured in self-conscious clubgoers compelled to dance to its music, stylish women singing along to songs that haven’t yet been released, and ostensibly heterosexual dudes snapping stage shots with cell-phone cameras, then it can be argued that the Bravery is already the biggest rock act in the world.

But mostly, the band is in limbo. The guys take meetings with Jay-Z (“He was just wearing a sweater and jeans,” says Burulcich. “We had a bunch of Coronas.”); their video makes Rolling Stone’s “Hot List”; they book sold-out U.K. tours. But, without an album out, they’re not exactly famous. “I ran into this high-school friend of mine at a Baltimore rest stop,” Hindert says, “and I had to make a decision: Do I tell him just how well things are going, we’re signed to a major label, blah-blah-blah, or do I just tell him things are cool?” Surprisingly, he opted for modesty. “I figured it would be better to wait until he finds us on MTV.”

Counting down to the album’s release date, Endicott says he’s filled with as much doubt as excitement. He’s given a lot of thought to the case study of the Strokes, who went from rock and roll’s Leonardo DiCaprios to the genre’s Ben Afflecks in about eighteen months. “That’s why the hipster music community sucks,” says Endicott. “A 14-year-old girl who’s really into Nelly knows more about music than one of these music snobs, who one minute say they love it and the next minute, when everybody’s heard of the band, say they hate it.”

The hipster music community is already returning the love, speculating that the Bravery’s half-life might be even shorter than the Strokes’. In a review of “An Honest Mistake,” the indie Website Pitchforkmedia.com wondered if the band “will be done in the US by the time they get their presumably photogenic faces on Fuse and MTV2, if they’re not done already.” (Still, they gave the single three and a half stars.)

And what happens when rock and roll’s goth-glam revival proves to be as short-lived as Johnny Marr’s solo career? “It’s going to be interesting to see what sort of staying power these alt-British-eighties bands have,” says Comaskey, who now books talent for Crash Mansion. He thinks the Bravery is the band most likely to anticipate trends and adapt: “I don’t think they’ll be doing the Robert Smith eyeliner and jet-black dyed-hair thing for too long.”

The Strokes went from rock and roll’s Leonardo Dicaprios to the genre’s Ben Afflecks in eighteen months.

Galli hopes to avoid premature obscurity by thinking two steps ahead. He’s already encouraging the band to work on its follow-up LP. “The second record,” he says. “That’s the record that makes a career.”

But nothing is guaranteed. The Bravery’s video for “An Honest Mistake” finds the band performing in an elaborate Rube Goldberg device. Toppling dominoes set off mousetraps, falling anvils crush levers, and bowling balls knock over milk bottles, until finally a flaming arrow is fired at a bull’s-eye—and completely misses its target. The question is obvious: What if we do everything right, and we still don’t succeed?

Two weeks later, Endicott is one of many white men in London’s Hammersmith Palais, sound-checking for a New Musical Express–sponsored show in which the Bravery will be sharing a stage with its unacknowledged artistic and sartorial muses, New Order. The performance is just one of sixteen the band has planned on its second sold-out tour of the U.K.

Endicott is noticing differences in how they’re being treated this time around: “When a 55-year-old lady recognizes you at the airport, that’s sort of a testament.” But lest his rock stardom prove fleeting and he end up looking like a jerk, he quickly adds a self-deprecating remark. “We’ve stepped up from the roach motels to the Holiday Inns,” he jokes. “It’s not exactly glamorous, but you get a lot of free shower caps.”

The U.K. tour is immediately followed by a 28-date American run, culminating in the Coachella festival in May. “We’re booking a show in Japan for the end of July,” Endicott says by cell phone. “I never planned anything that far in advance. I’m more organized than I’ve ever been in my life.”

The schedule is rigorous, but Endicott is glad for it. “When you’re in a band that’s going nowhere,” he says, “on a day-to-day level that’s less stressful, because you can sleep all day, but the stress there is much worse, because it’s a soul-sucking, staring-into-the-void stress.” He’ll take the endless anticipation and frustration and calculation of being in a band that’s got a shot any day.