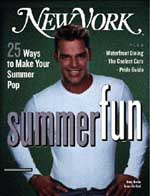

Two days after bringing midtown traffic to a grinding halt during an alfresco Today performance, Ricky Martin is seated in a spartan L.A. photo studio, a serene island in a sea of doting publicists, bodyguards, friends, and stylists. Even up close, the 27-year-old pop star looks surreally perfect – like a shiny mannequin from a Barneys window come to life. For almost three hours, as a photographer clucks his approval, Martin happily serves up a series of sultry expressions and coy contortions, a performance that would seem comic if it wasn’t so effective. You don’t get to be the hottest pop star in the world without knowing your way around a camera. Indeed, in the decade since Martin grew out of Menudo and decamped for New York and a gig on General Hospital, the Puerto Rican prodigy has managed to transform himself into a global juggernaut. In Latin America, Europe, and parts of Asia, where he has long been a household name, Martin’s four solo albums have sold more than 15 million copies. In America, his eponymous English-language CD sold 4 million in four weeks and made Martin the poster boy for America’s endlessly heralded Latin invasion. A catchy, slickly produced amalgam of Latin fusion, classic rock, and bubblegum pop – it spawned a single, “Livin’ La Vida Loca,” that has become the summer anthem of 1999. As his electrifying performance at the Grammys made clear, he has the kind of charisma that prompts normally sober critics to compare him gushingly to Elvis and the Beatles. Martin’s upcoming seventeen-city tour, which kicks off in Miami next October, includes two nights at the Garden on October 28 and 29. Tickets go on sale July 10. He’s not completely immune from the perks of celebrity (“Ricky feels like mashed potatoes!” someone barks during the shoot, and a woman dutifully trundles off to fetch some), but in the midst of this madness, he still seems surprisingly down to earth. In person, he is winningly earnest and intensely physical – the kind of guy who looks straight in your eyes and touches your arm while discussing his sister in San Juan. New York’s Maer Roshan met with Martin last week, just hours before the singer’s appearance at a local record store forced police to shut down several city blocks.

Maer Roshan: I know you’ve been at this for a long, long time, but did it scare you to suddenly blow up so fast? Did you ever imagine that things would get so big so quickly?

Ricky Martin: You mean in America?

Yeah.

R.M.: You know, in a way I never wanted to be overwhelmed by America. It can be a scary place. But I had a mission, and the mission was to get rid of stereotypes and make people understand a little bit more of what a Latin performer, Latin sound, can be. It’s always been my plan.

But the roller-coaster aspect of all this must be terrifying sometimes.

R.M.: You have to stay in touch with your mind and your soul, because it’s not just a problem of it being terrifying or overwhelming – it can be fatal. Looking back at the history of those in this business who weren’t ready for it, who couldn’t deal with the applause and ended up dead or on drugs – that’s something I don’t want to face. I want to be happy.

How will you manage that?

R.M.: With silence. That’s my medicine. The adrenaline of press conferences, photo sessions, the energy of the concerts, it’s like a drug. It’s addictive. There’s nothing like it. And when it’s over, you have to lock yourself in a room and just be alone.

On my way here, I heard on the radio that some people had camped out at the Beverly Center for fourteen hours waiting for you to arrive. And right now there are probably 10,000 screaming people out there, all waiting to see you and touch you and get a piece of you. How do you possibly prepare for something like that?

R.M.: It’s not really a challenge for me. I get a lot from it, too. Just looking at people’s eyes when you’re signing autographs, you know, at an in-store or in a concert. People think when I’m up here, because of the lights and everything, that I can’t see the audience. But I can – I do see the audience and it’s my food … I don’t know how to say it. The way I feed myself is looking at people’s reactions and people’s faces. You just try and absorb everybody. It’s pure energy. And all these people, all of them are telling you, “You’re doing great, man.”

People cite the Grammy Awards as the pivotal turning point for you. When you look back on your performance that night, what was it about you that caught the fancy of so many people?

R.M.: You know, when people think Latin, they’re expecting a stereotype, and all of a sudden they got this guy with, yes, very intense Latin influences but also with a very futuristic visual aspect and a different style, and it kept them off-balance. And the fact that I make the audience part of the stage and raised the sound level – it was like theater, different than the Grammys usually are.

It also seemed like you actually got off on being there, which is more than you could say for a lot of the performers.

R.M.: You kidding me? Look who I was performing for! Besides the millions of people watching, I was performing for the industry, and I need to be respected by my peers. When you see Sting looking at you and analyzing what you’re doing and analyzing your style and the way you’re coming across, that’s beautiful. I’m young and everything, but you know, look at me. I have something to say.

Was there a moment when you got off the stage and realized, “Damn, I just became a superstar”?

R.M.: No. But I said, “This is going to be awesome.” Laughs “This is going to be beautiful.” I said to myself, “Hold on tight, buddy, it’s gonna happen right now.”

It’s occurred to me that much of your mystique is derived from this raw sex appeal, and yet you’ve consciously shied away from it sometimes. You’ve complained that the focus on you as a sex symbol takes away from your credibility as a musician.

R.M.: I believed that in the past but not really now. Because if you start looking back – I mean, look at Elvis. He was a sex symbol, and now he’s a legend. The same thing with Valentino. Even Diana’s kid, the prince, he’s become a sex symbol. You know, in the end sexuality is important. We are here because of a sexual relationship, and on top of that I am a Latin guy. When you meet someone in the Latin culture, you kiss immediately. “Hi, nice to meet you – mmmmuhhh.” So I am not going to try to go against the tide. I’ll just have fun with it while I still have it.

So you don’t mind being a sex object anymore laughs. Me neither!

R.M.: An object? I don’t know. I am a person too. A man that has feelings. And at the same time, I want respect from the audience, and in order for me to get respect, I have to have some quality in my music. Not just shake my ass.

In the same interview, you said, “What I say about sexuality is, I leave it for my room and lock the door.” Given your amazing success and the realities of modern media, do you really think you can keep the door locked for much longer?

R.M.: You know, I’ve done it for fifteen years, and maybe it’s going to be different now. But in the end, it’s my space, it’s my house, and it’s not only for me, but also I have a mother, and I have a sister and brothers, and I have a father. And some people want to cause them pain. People are out there just wanting to destroy it. They see you happy; they don’t like when they see you happy. They just want to break that magic. So you’ve got to ignore them and just pray for those souls that just want to do you harm. I don’t owe them anything.

Whom do you see as your role models in this business? I know you’ve become friendly with Madonna.

R.M.: Having the opportunity to work with her, yes, I learned a lot. I learned that it doesn’t matter where you are or who you are, you have to be willing to listen, and not everything has to be the way you want it to be, nonnegotiable. Madonna goes into a studio and she says, “What do you think? What do you like? What do you hate?” But there’s a lot of others, like Sting or David Bowie, I’ve learned from as well.

Why has Latin music taken off here all of a sudden? Is it a real change or a temporary fad?

R.M.: Besides the fact that the Latin community is the fastest-growing minority in America, I think it’s a phenomenon that is not only happening here; it’s been happening in Europe for the past few years, and in Asia, stronger than ever. All over, people are becoming open to different ideas and different cultures.

But there have been complaints that the Latinos who are most successful are invariably the ones who seem the least, well, Latino. Someone in Time magazine claimed that darker-skinned Latins still still can’t land a contract. What do you think of that?

R.M.: I can’t get any more Latin! It’s so racist to say that because you are dark-skinned you cannot make it in America. Whoever wrote that should go to jail or at least get sued. It makes me angry. People forget that there’s a long list of artists who have been doing this for so many years, like José Feliciano, like Gloria Estefan. Santana played Woodstock! So this so-called Latin movement isn’t new. There are a lot of artists in Latin America who have all the tools to cross over. It will happen. It’s just not there yet.

What do you think Anglo culture has to learn from Latin culture?

R.M.: Long pause Faithfulness.

Your success has also renewed a lot of interest in Menudo, which some former members now remember as cruel and exploitative. What was it like for you? Do you have good memories of that time?

R.M.: It was a lot of work. I look back, and I can’t believe the hours I had to work, and I was a young kid and I gave up a lot. To be a kid, to work for twelve hours a day. God, that could be lonely! But they tell you, Hey, if you’re not happy, you can leave! It’s okay.

And then you were forced to retire when you were, I guess, 18.

R.M.: Seventeen.

Seventeen. And you moved to New York. What neighborhood did you live in?

R.M.: I lived in Astoria, in Long Island City. Everyone but me was Greek.

What was your life like at the time?

R.M.: Very quiet. I wanted to be outside of Manhattan. I just needed to spend time with myself. It didn’t matter where I was. But I stayed in New York because I wanted to study acting, and I didn’t want to go to L.A. because it was too far from home. So I thought New York is perfect, you have, you know, the theater, the culture, museums. You can grow intellectually. And at the same time, I had anonymity.

Anonymity.

R.M.: Anonymity. New York City for anonymity – it’s perfect. For me, it was so important to walk through a park and sit on a bench and just look at people and just think about my stuff. Because for the first years of my career in Menudo, it was all about giving, giving, giving, giving. They said, “You have to wear these clothes and wear this haircut and sing this song.” So after a while, I lost my personality, who I am. What I hated and what I liked. Because I didn’t know myself back then. I didn’t know myself at all.

And now you’re back where you started in a way. Even in New York you probably can’t walk the street anymore, can you? I mean, without being recognized?

R.M.: It depends what kind of beard I wear laughs.

What makes you happy?

R.M.: Laughs Simplicity. That’s all.

I know that you went through a lot of religious experimentation, like Scientology and Judaism. What were you looking for?

R.M.: Yeah, Judaism, but also a little bit of everything – Buddhism, everything. I grew up being Catholic, a beautiful religion. But you have to search. You cannot have tunnel sight. You have to keep looking for meaning.

If you went to my temple, I’d probably go more than once a year.

R.M.: Laughs Maybe I’ll start.

It occurred to me watching you on the Today show that you’re living the ultimate fantasy. You’re young and rich and famous and healthy and beautiful and talented – right now you kind of own the world. And I wanted to know, what does the

world look like from that vantage point?

R.M.: Oh, it feels small laughs. I don’t mean that in an arrogant way. It just gets much, much smaller. The other day, I was talking to my father, and I was telling him, “Dad, you know what it is to go to New Delhi in India and to be recognized?” And when it comes to music, once again, every fucking sound has a link. It’s all the same. You listen to Hindu sounds; they are very similar to the Gypsy sounds from the southern part of Spain, and that makes a bridge to Latin America. Asian sounds and Latin sounds are the same. The world is suddenly smaller than it ever seemed.

It seems that a frustrating part of the modern celebrity thing is having all these nervous handlers, people who follow you around and look after you and get you mashed potatoes and watch your every word. And I wonder if you ever feel like just jumping into your car and taking off and leaving them all in the dust …

R.M.: I’ve done it.

Is it harder and harder to do that?

R.M.: No, you have to do it. Even if you have to scream to be left alone, you do it. “You know what? Leave me alone! I need to spend time for myself. I don’t want a phone call from my manager! I don’t want a phone call from anybody. I’m not even picking up the phone.” Laughs You know what I’m saying? Because that’s the only way you can step out of the picture, analyze what you’ve done, analyze what you want to do, and go back and make it happen. At the end of the day, that’s what the audience is looking for: sincerity and spontaneity at the same time.

Do you get worried that you won’t be able to keep this going?

R.M.: It’s something that every entertainer worries about. But I’m telling everybody, I have great producers, I have great musicians. I am always looking for new, new sounds and new things. People are not going to be tired of me. In ten years, I won’t be doing what I’m doing now. Yeah, I sometimes worry. But I don’t want to be too hard on myself. You know, I haven’t done too badly. I’m always whipping myself, and now I just need to keep it simple.

Do you ever get scared onstage?

R.M.: No.

What does it say about American culture at this particular moment that the two biggest stars of the summer are you and Jar Jar Binks?

R.M.: Jar Jar Binks?

From Star Wars. The poor imaginary bastard was just denounced as a racist and outed by The Village Voice.

R.M.: Really? Laughs Too bad for him. But I’m planning to be around for longer than just the summer, dude.