Time marches on. Don’t it? In its wake, it leaves these snapshots, some burnished, some fuzzy, some sharp like a razor to cut off your head. David Johansen, wily old New York rocker, noted chameleon, actor, survivor, has dealt more face cards than most over the years, some from the bottom of the deck, some not. But what are you gonna do? It’s a jungle out there, you got to keep moving, as most any savvy Yeah Yeah Yeah, Moldy Peach, or El-P already knows from watching a hundred Behind the Music reruns. So call this a cautionary tale, a particular kind of Big City music scrapbook of 35 years of being cool and staying sane, at least mostly.

When it comes to pictures of David Jo, like most downtown fans alive then and now, I’ve got a thing for the way-back nights of flaming youth, when Johansen was the lipstick-killer lead singer of the New York Dolls, a group more fabulously hip, more full of “promise,” more indicatively “New York” than almost any in the history of promising New York groups.

Here’s a postcard from 1972: David, the Staten Island–bred ingenue of the band, sitting on the curb outside the Mercer Arts Center (which would soon collapse) amid the garbage cans and graffiti. Draped in lime-green satin, tarty pink boa around his neck, a short stack of pancake on his cheeks, he is the perfect parody of Greta Garbo in Ninotchka, or Bette Davis in Jezebel, or maybe some cranked-up Shangri-La, except for the spreading sweat spots under his arms. He’s ripping off his platforms, which are painted blue. “Fuck these boots,” the Doll screams, throwing the footwear into the street because it’s not easy to sing raunchier and sweeter than Jagger ever dreamed, with the band laying down the next link of what would get called punk a few years later around the corner at CBGB, and do it all in eight-inch heels, with David Bowie in the audience, too, and have your feet not be killing you.

“You know,” says David Johansen, “I had a picture of myself when I was a kid, how I’d look when I got old. I look in the mirror and think, This is pretty much it.”

As Joey Ramone and the rest readily agreed (pre-Smith Morrissey wrote a book about them), there had never been anything like the Dolls and there wouldn’t be again. Five straight outer-borough white boys dressed like girls (except Johnny Thunders, né Genzale, of Queens, who wouldn’t) singing about making it with Frankenstein, the Dolls were a flip book of funky New York post-hippie glitter, whether they were practicing in a bicycle-repair shop on West 82nd Street, with the door locked so they wouldn’t steal anything, or breaking up in a trailer park beside a swamp with Johnny T and Jerry Nolan going nuts because they were in Florida and there was no dope in Florida, man. Then came the sad pictures: Johnny and Jerry, RIP, and Billy Murcia too, their first drummer, a Colombian from Jackson Heights, dead in a London bathtub.

After that, of course, came Johansen as Buster Poindexter, with his Jimmy Neutron pompadour, tux, and little half-socks, cracking wise, leering goofy, the face that spawned a hundred miles of conga lines (wedding-band players still grouse about those nightly doses of “Hot, Hot, Hot”) – a decade of a joke that wouldn’t die. Johansen says Buster started the way everything does with him: offhand, by accident. Managed by Steve Paul, who ran Steve Paul’s Scene, where the Doors, Hendrix, and the Velvets played, he’d trudged through the early eighties fronting the David Johansen Band, stuck in permanent second-banana mode. One night, opening for Pat Benatar, he looked out into the crowd and saw only a mindless sea of pumping fists and said to himself, “I’m officiating at a Hitler Youth rally … This is what it has come to.”

A few days later, he was in the old Tramps, on 15th Street, where he’d hung out since the days when he read the newspapers to the 325-pound blues singer Big Maybelle, who never learned to read them herself, not that she would admit as much. There was an open night, one day a week, to try out this new thing, this Buster thing, the lounge-act cat who knew every “pre–Hays code” rock-and-roll song ever written and made up the rest. It was a lot of blowsy eighties fun, an escape from being “David Johansen.” Tony Garnier, Dylan’s guy, played the bass. Jimmy Vivino was in there, too, all the session stars. It took off, got out of hand, which was fine. The money was good, more than a month of Tuesdays at Mercer Arts Center’s Oscar Wilde Room. For a while it had a Latin tinge, Buster, the sly musicologist, suddenly turning up with a thousand Cuban charts back to Machito, Arsenio Rodriguez, and the rest. But the corporate accounts, the ones who ran the parties where stockholders got to put lampshades on their heads, wanted only “Hot, Hot, Hot,” the song Johansen calls “some dangerous karma, the bane of my existence.” After a while, there was barely enough energy to grease the pompadour.

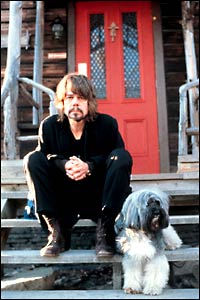

So now there’s this. Johansen has been a Harry Smith for a couple of years, with two albums of deeply strange folk songs in the can, including the current Shaker, the cover of which shows the old Doll, stark and austere, standing in a windswept graveyard wearing a duster, like Jack Elam in Once Upon a Time in the West. It has been working, too, with Johansen’s famously gruff pipes gnarled up into the mode of an itinerant singer, a modern-day Dock Boggs, squinty from a night on the Greyhound, haunted by dark tunes like “Oh, Death,” which quotes the Reaper himself: “Oh, Death … God’s children pray, the preachers preach, the time of mercy is out of your reach / I’ll fix your feet so you can’t walk, I’ll lock your jaw so you can’t talk.” But then, even with a touch of Just for Men in his grifter’s beard, Johansen has always been able to get himself up for a part, even when playing Joe E. Ross’s Toody role in the loopy movie of Car 54, Where Are You?, one more New York icon.

Again, he claims, it was an accident, something he shambled into, in the shambling way he keeps his money in a plastic bag because he doesn’t like the way wallets bump out his pocket, like the way he’ll get to a show and realize he’s forgotten his harmonicas, again. “Allan Pepper from the Bottom Line called me up to see if I wanted to do a gig for his twenty-fifth-anniversary show. I said I’d been working out this string-band thing, playing these old songs. ‘Okay,’ he said, ‘what’s your name?’ ‘Shit,’ I said, ‘call us the Harry Smiths,’ ” Johansen relates, invoking the polymathic presence of the filmmaker, painter, and all-around beatnik gnostic shaman whose multivolume collection of early recordings by black bluesmen and white hillbillies, The Anthology of American Folk Music, has taken on the mantle of a Dead Sea Scroll of rock and roll. It was Smith’s collection that Bob Dylan used as a map when he and the Band holed up inside Big Pink making the famous Basement Tapes, which has been characterized as a sonic Invisible Republic depicting “weird old America.”

“Yeah, call us the Harry Smiths. That way people will know what we’re doing,” Johansen said. Told that perhaps not that many people would immediately know what a band called the Harry Smiths was doing, Johansen says, like a man who has come to terms with the perimeter of his marketplace position, “Good, because those eleven people, they’re my people.”

Being a Harry Smith may not be as Zeitgeistical as being a Doll, but how much Zeitgeist can a boy who grew up riding his bike to the Staten Island Ferry stand in one lifetime? For years, people, including ex–band mate Syl Sylvain (né Mizrahi), have accused him of “denying” his Dolls heritage, as if being onstage looking like the Avon Lady blew up in his face was somehow beneath him, something Johansen finds “not right … because the Dolls are history, which is something I respect because those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it.” Being a Harry Smith suits him. “You know,” he says, slouching in a Chinese restaurant, “I had a picture of myself when I was a kid, how I’d look when I got old. I look in the mirror and think, This is pretty much it.”

According to Johansen, even when he was growing up in blue-collar West Brighton with his five brothers and sisters, getting kicked out of Catholic school, playing with his first bands, the Vagabond Missionaries and Fast Eddie and the Electric Japs (“Sometimes I was Fast Eddie, sometimes I was a Jap”), he always thought of himself as a folk singer.

“Hillbilly music like the Carters, Little Walter, white people, black people, it is all folk music … I’ve always been into this. Folk music is this New York thing. It was around, and not just like Judy Collins and Peter, Paul & Mary, songs they sang in the red-diaper summer camps. There was the Harry Smith stuff, the stuff beneath the stuff. They might call it ‘weird old America,’ but for me it was ‘weird old New York.’ We’d go to the Cafe Au Go-Go, Muddy Waters would play there. The first record I ever bought was ‘Tail Dragger’ by Howlin’ Wolf, a 10-cent single at the Do-Del record shop in Staten Island. I put that on, and it was like, what world is this from? It was the same in the Dolls. I pictured myself as Janis Joplin, who to me was always a folk singer. I loved Janis Joplin like a queer loves Judy Garland.”

“Being a Harry Smith keeps me sane,” Johansen says. In a world of rock-and-roll ephemera, tapping into the tangled roots of things like “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground” by Bascom Lunsford, “James Alley Blues” by Rabbit Brown (“Sometimes I think you’re too sweet to die / sometimes I think you should be buried alive”), and Jim Jackson’s “Old Dog Blue,” all of them recorded more than 70 years ago, has a kind of permanence, a whiff of eternity. When you’re 52, no longer the ingenue, an Alan Watts reader with a late-onset authenticity jones, eternity is nothing to sneeze at.

Plus, Johansen says, some things are just so old that they get new again. Ralph Stanley’s version of “Oh, Death,” which Johansen does on the first Harry Smith disc (with all due respect, better than Ralph), was on the surprisingly high-selling O Brother, Where Art Thou? collection. Maybe it’s just more post-9/11 anti-irony, but since the White Stripes did a version of Son House’s “Death Letter” (David cuts them too), the kid up the street has been coming by the house asking me if I’ve got anything by Blind Willie McTell, which, of course, I do.

Who knows? Being a Harry Smith could be a bonanza. “Furry’s Blues,” the first cut off Shaker, has been picking up some airplay, and not just on NPR. “It’s not heavy rotation,” Johansen says, “but it’s on there.” It’s almost enough to make you want to drive to Memphis, go out to where Furry Lewis is buried, and tell him his tune that begins “I’m gonna buy me a graveyard of my own / so I can kill everyone that have done me wrong” is getting a bit of a tumble in George Bush’s U.S. of A.

Not that Johansen hopes the tune becomes another “Hot, Hot, Hot.” Who needs people screaming out “Furry’s Blues” all the time, like how, say, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs – if things go a certain way – are looking at a lot of disgruntlement if they don’t play “Our Time” every night for the next few decades.

Still, Johansen doesn’t expect to be a Harry Smith forever. He’s been listening to some twenties Duke Ellington material he’d like to play, trying to raise his guitar skills by buying a book of chords and learning “at least one a week.” But for tonight, the Harry Smiths will do. Parking his 1989 Pathfinder, which he refers to as “an ashtray on wheels,” Johansen is at the Bottom Line, where the band started. Probably the best acoustic string band in town, with his long-time confederate Brian Koonin on guitar, Larry Saltzman playing dobro, Kermit Driscoll on bass, and drummer Keith Carlock, the group sounds great, but David’s voice, as much a barbed missile as ever, is feeling a little “extra ravaged” owing to an evening spent singing Howlin’ Wolf songs. Channeling the Wolf is rough on the the old throat cords. But no matter; David’s got his little vial of Saint-John’s-wort for “my onstage depression,” plus now he gets to wear sensible shoes, not platforms, and sits down, his legs crossed, in the perfect image of that photograph of Robert Johnson, the one where he’s smiling with the hat on his head.

For hours it rolls on, this tour of the dead and forgotten. Some guys Johansen does better than others. Charley Patton’s hard. Most of his records are so scratchy, “he sounds like Black Tooth from the Soupy Sales show,” the singer says. But Lightning Hopkins, Johansen’s got him nailed. Dock Boggs too, “Oh, Death” coiling up your spine like an evil shadow. Then, in the end, when he does the Dolls’ great teen-passion saga “Looking for a Kiss,” complete with the “When I say I’m in love, you best believe I’m in love, l-u-v” intro, it fits right in, one more missive from a weird old New York gone by. Ditto one of Buster’s campiest showstoppers, “Heart of Gold,” transformed into an elegiac plea – or a coded message to a whole new crop of ingenues – just the sort of strange stuff that might have raised Harry Smith’s eyebrow should he have encountered it on a 78 during one of his collecting hunts in a Greenwood, Mississippi, garage or a basement out in Queens.

“I’m a whore, but I’ve got a heart of gold,” Johansen sings. “I’ve been bought and I’ve been sold, but I still need protection from the cold.” Least we can do is take the old coquette in.

Buy it on barnesandnoble.com

David Johansen’s recent CD Shaker