On February 1, after an opening-night performance of his one-man show, Thom Pain (based on nothing), James Urbaniak headed home to Noho with his wife to wait for the reviews. “You don’t go to Sardi’s anymore to buy the late edition—you go home and go online,” he says. After reading the Times review at 1:30 A.M., he phoned the play’s author, Will Eno, who hadn’t planned to wait up. But as it turned out, Eno’s girlfriend had already found it, and told Eno, “Will, you really should read this.”

The review wasn’t just supportive or exuberant; it read like something a playwright or actor might compose in a daydream while lounging in the bathtub. “It’s one of those treasured nights in the theater,” Charles Isherwood wrote; Urbaniak, he said, “establishes himself as a significant artist with his sly, heartbreaking, exquisitely calibrated turn.” Thom Pain (based on nothing) had been well received during a run in London and a stint at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, but this was success of a different order: It sounded a starter’s pistol that sent theater fans racing toward the box office. The day of the review, the show sold $152,000 worth of tickets. It’s now sold out through mid-April. Suddenly, Thom Pain is the most prized ticket Off Broadway—“The Producers, writ small,” Urbaniak says with a laugh—and true enough, Urbaniak, its sole star, is almost as hot as Matthew Broderick and Nathan Lane rolled into one.

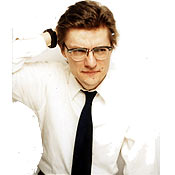

Urbaniak is 41 but looks at least ten years younger. He’s tall and knife-thin, and wears pebbled, plastic-rimmed glasses—a hipper, more flattering version of the horn-rimmed spectacles worn by his character, Thom Pain. He speaks, like his character, in well-thought-out, precise sentences. Unlike Pain, though, he occasionally interrupts himself with a sharp burst of staccato laughter, which seems intended to let out tension when he’s addressing something he’s not entirely comfortable with—as when he says, in regard to the hubbub, “I have a pretty guarded approach to show business. I have a healthy skepticism. So I’m just starting to embrace—ha ha ha—the success of it.”

As an actor, Urbaniak is adored by downtown insiders, vaguely familiar to the layman, and entirely self-taught. As a teen in Marlboro, New Jersey, he floated through his studies—“I was kind of a fuck-up in high school,” he says—got rejected from Rutgers, then headed off to Brookdale Community College. He lasted a couple of years, did a few plays, juggled half-considered career options—journalist, graphic artist—then dropped out to become, in his words, “the quintessential slacker kid.” He listened to Elvis Costello and Talking Heads. He hung out with a guy he’d met in college who was obsessed with old movies. He discovered James Cagney. He temped. “I had vague ideas about becoming an actor,” he says, “but I wasn’t doing anything about it.”

Then he met Karin Coonrod, a former schoolteacher from Monmouth County who’d quit to become an avant-garde theater director in New York. She persuaded Urbaniak to join her, and they started a downtown theater company, Arden Party. He worked exclusively with that group for six years, then started branching out. His career can be measured in distinct leaps forward, like a player in a board game grabbing a card that tells him to jump ahead six spaces. The first event was meeting Coonrod. The second occurred in 1997, when indie-film director Hal Hartley cast him as the lead in Henry Fool. “Suddenly, I was starring in a movie,” says Urbaniak. “That opened the door to get an agent. My last week of temping was literally the week before shooting began.” Later, he landed a role as Robert Crumb opposite Paul Giamatti in American Splendor, the part most people know him for—unless, given American Splendor’s blurring of reality and fiction, and Urbaniak’s uncannily mimetic performance, they thought they were actually watching Robert Crumb.

The third leap forward is, of course, Thom Pain. The play is a cerebral and satisfying bit of theatrical swordsmanship, full of quotable one-liners—“ ‘You’ve changed,’ she said, the night we met”—and mischievous stunts, as when a plant in the audience storms out halfway through. But Urbaniak sees it as a novel repackaging of a classic tale. “It’s a guy with problems. He tries to work them out. He goes through a climactic experience at the end. And then he’s ready to move ahead.”

The show’s been extended, and Urbaniak’s told producers he’ll stay on as long as Labor Day. He performs eight times weekly, with only Mondays off. “Napping is essential,” he says of his regimen. “Nap, snack, act. That’s my mantra.” Between the London run and the current stretch at DR2, he’s been playing this character for more than a year now. That’s the complication of starring in a theater hit: It’s like being handed a winning lottery ticket that you have to wait months to cash in. Then again, “I’ve never really been in a hurry in my life,” he says. “I think I’m pretty ambitious. But when I was in my twenties, I was working with my own little company downtown—that was my university. I always thought, When I’m in my thirties, I’ll start to make a living. And sure enough, I made Henry Fool. Now I’m 41, and I’m in one of the most high-profile theater experiences I’ve ever been in. And it looks like, theoretically, there’s a new chapter opening up.”

“You want to get out of the pigeonhole where you’re the funny little guy with glasses who reads the data to Bruce Willis.”

But if some actors dream of being the next Marlon Brando or the next Tom Cruise, Urbaniak sees Paul Giamatti as his model. “I admire guys like Paul, or Phil Hoffman, or William H. Macy—character men,” he says. “I see myself as one of those guys. Paul started out playing funny little supporting guys in movies, and now he’s starring in them. That gives all the character guys hope.” It’s as though he’s describing a guild that meets in a beer hall once a month. And even for the blue-collar workers of the acting world, fame has its uses. “When you start to get the high-profile roles, it’s not about being famous—who cares about being famous?—but it means you get more choices,” he says. “That’s all any actor wants. You want to get out of the pigeonhole where you’re the funny little guy with glasses who comes in and reads the data to Bruce Willis. I’ve played a lot of guys like that. And I can be the funny guy with glasses. But I’d also like to be the guy who gets the data read to him.”

Urbaniak reads all his reviews, good or bad, and like a true autodidact, he talks about them with the detachment of a scholar. “If the person has a valid point, you consider it, and if they don’t, you don’t,” he says. But while performing Thom Pain in London in 2004, Urbaniak spent a lot of time watching the Olympics, and he told a reporter about his fascination with gymnasts, who perform amazing feats “and then the commentator will tut and say, ‘Oh dear, she blew the landing.’ ” I remind him about it and he laughs his staccato laugh: ha ha ha. “It’s just so weird,” he says. “These people are performing at the highest level, and then someone picks on the fact that they didn’t hold their arm just so. But I guess that’s what happens when you’re at the top of your game.” He doesn’t finish the thought—that every so often, someone pulls off a perfect ten. The performer executes the most amazing acrobatic maneuver, then sticks the landing, really plants it, and holds there for a moment to savor it, leaving the judges and the audience with nothing to do but cheer.