Because they traffic in exaggeration, all farces are a bit disorienting—not as forbidding as a foreign language, more like a different dialect. William Hamilton, cartoonist, writer, playwright, has written in White Chocolate a truly preposterous farce that, even so, has a thing or two to tell us. It starts with Brandon and Deborah Beale, an affluent New York couple (he a Boston Brahmin, she a wealthy New York Jew) waking up one morning as blacks. No explanation is given, as how could there be? No one—not his sister, Vivian, not their daughter, Louise—recognizes them. They are assumed to be clever impersonators hired for a madcap party to celebrate Brandon’s appointment as director of the Metropolitan Museum, to be announced this day, unless the appointment goes to Ashley Brown, a high-level black employee. That is much less likely, given the millions with which Deborah’s ambitious father has endowed the museum.

From this springboard, the play takes off in a dizzying spiral, not least because Louise has got herself engaged to and impregnated by Winston Lee, a Chinese-American, and the unhappily married Vivian and the visiting debonair Ashley promptly hit the sack. Hamilton has frantic fun lampooning everyone: Wasps, Jews, blacks, Chinese; also life in general. As a cartoonist, he knows how to create striking stage images with one-liners by way of captions; as a playwright, he is adept at milking a situation for every drop of comic potential.

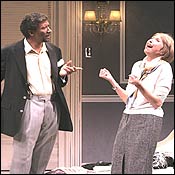

It would require a good deal of obtuseness to take offense at what might be called racial jokes. They are presented only to be punctured, and with no race or class spared. I observed that the many blacks in the audience laughed and applauded even longer and louder than the whites. David Schweizer’s fluid direction helped manfully, as did James Noone’s witty décor and David Zinn’s sassy costumes. The cast is flawless. Reg E. Cathey’s upper-crust accent tops off his marvelously mercurial Brandon. Lynn Whitfield’s black-on-Jewish palimpsest makes a delicious Deborah. Julie Halston carries off Vivian’s genteel outrageousness with panache, and Samantha Soule (Louise), Paul H. Juhn (Winston), and Erik LaRay Harvey (Ashley) handle the supporting roles as expert farceurs.

Even if some of the nonstop jokes are less sparkling than others—a few indeed a trifle sophomoric—the whole package is delivered with an efficacy to make FedEx envious.

Playwright and accused plagiarist Bryony Lavery is at it again with Last Easter. Not at plagiarism (the script carefully acknowledges all sources, even a recipe for linguine), but at playwriting, her greater sin. I thought little enough of her Frozen, though at least the subject was interesting and the cast excellent. Neither can be said for Last Easter, which is worse than bad, repellent.

“Hugh Landwehr’s set represents a junk shop, which, given what the author is peddling, may be viewed as appropriate or redundant.”

Written on the page as something Lavery imagines to be free verse, and in language she clearly thinks is poetic, this clunky clinker is pretentious, smug, grandiose, and empty. It purports to address such grave subjects as cancer, death, religion, God, Lourdes (with or without miracle cures), art, love, friendship, euthanasia, and motoring through France, with nothing of originality or interest to say about any of them. The characters are Gash, a singer–female impersonator; Leah, a prop-maker; June, a lighting designer; Joy, an actress; and Howie, a stage technician. Gash’s specialties are singing snatches of pop songs and telling endless corny old jokes. Leah is an American working in England, Jewish, and boring. Joy is a foulmouthed drunk, whose every speech contains one or more fucks or fuckings; June is sensitive and dying of breast cancer. Howie, Joy’s former lover, is a suicide, but keeps mutely reappearing. In Act One, last Easter, the friends take June to Lourdes, where she may have had a remission. In Act Two, this Easter, June, in unendurable pain, persuades her friends to suffocate her with a plastic bag, after which they memorialize her.

Lavery introduces a number of purportedly prestigious touches. June raptly rehashes an exhibition sign’s commentary on Caravaggio’s painting of the Judas kiss, Gash adduces jazzy movie trivia, Joy chants a Buddhist mantra, Leah points out that a person on Betelgeuse with a telescope would see dinosaurs on Earth, and Joy rhapsodizes about a brand of Polish vodka. All characters dribble French phrase-book snippets, plus one in Italian. To prove her good faith, Lavery cites a page’s worth of sources, which only goes to show what a magpie’s nest her play is.Though not so specified in the text, Hugh Landwehr’s set represents a junk shop, which, given what the author is peddling, may be viewed as appropriate or redundant. Veanne Cox tries to make something out of June by infusing her voice with a plangent nasality; Jeffrey Carlson is uncannily persuasive as a female impersonator. Clea Lewis’s charmless and squeaky-voiced Leah and Florencia Lozano’s blatantly unmodulated Joy are rough on the ear and eye. The wonder of it is that as good a director as Doug Hughes should have taken on a work for which he could do nothing, and it only harm to his reputation.

The Iraqi-American actress Heather Raffo embodies her interviewees in Nine Parts of Desire, conversations with a number of Iraqi women, ages 9 to 70, some in Iraq, some elsewhere. These women often speak in broken English (or are so translated), in inchoate emotional outpourings including Arabic words and local references that do not communicate. Sad as most of these stories are, they are not particularly revelatory; though they may elicit sympathy, they do not compel significant involvement.

Worse yet, Raffo is not actress enough to make us feel the speakers’ idiosyncrasies: She is not that different when she is 9 from what she is at 70, and most of her characterization consists of different ways of wearing the abaya, a robelike garment.

Strange activities are involved, such as a woman throwing heaps of old shoes into a river, saying: “Without this river there would be no here / there would be no beginning / it is why I come … The river again will flood / the river again will be damned [dammed?] / the river again will be diverted / today the river must eat.” This, too, is presented as poetry.

The title, in case you care, comes from the play’s epigraph, a sacred Islamic text that reads: “God created sexual desire in ten parts; then he gave nine parts to women and one to men.” Regrettably, nothing in the show justifies this promising motto.