Interesting who gets the dread kiss of the encyclopedist and who doesn’t. Look in The Oxford Companion to American Theatre, and you find a turgid old melodrama, The Shanghai Gesture, where John Patrick Shanley ought to be. Yet Shanley has labored fruitfully in our theater (as well as Oscar-winningly in film), writing numerous plays, some good, some not so good, but all hearteningly different from one another. If you advert to the three Shanley works that have opened here more or less simultaneously, their differences should smack you in the eye.

Doubt may well be Shanley’s best play to date. It goes back to his days in a Catholic school in the Bronx run by Sisters of Charity, and while it does not seem patently autobiographical, eight years at that school surely left their mark on the playwright. Another influence must be the recent revelations of pederasty in the priesthood. But what makes the play particularly absorbing is its enlightened objectivity. Shanley dedicates Doubt to the nuns and the good they have done and deplores their having been “much maligned and ridiculed.” Yet Sister Aloysius, the headmistress of St. Nicholas Church School, is the heavy of the play—though not, however, its villain.

Young Sister James reports to her that 12-year-old Donald Muller, the school’s token black student, although adequate academically, seems to have emerged troubled from a tête-à-tête with Father Flynn, the school chaplain, who appears to have accorded the boy his special protection. Worse yet, Sister James smelled alcohol on the boy’s breath. From this, Sister Aloysius is quick to surmise the worst, something the young nun—whose warmhearted innocence the headmistress regards with dubiety—never meant to imply. The boy, it is alleged, drank the communion wine, and Sister Aloysius is sure that Father Flynn put him up to it.

The plot in this short, intermissionless play thickens quickly. That is what makes Doubt seem longer and even richer than it is; conversely, the snappy dialogue and terse speeches make it seem shorter yet. But all four characters, including Donald’s sensibly tolerant mother, manage to be fully evoked in a wonderful dramatic shorthand. No one is totally right—even Father Flynn won’t reveal certain things—keeping us, too, in a state of doubt that Shanley says “can be a passionate exercise.” Doug Hughes, one of our major directors, has helped four terrific actors shine even with tiny gestures and expressive silences. It is often hard to say who put in those superfine shadings—author, director, or actors—and it’s safest to credit all of them equally. Consider, for instance, this bit of dialogue about a nun whose impending loss of eyesight Sister Aloysius wants to keep under wraps:

Sister A.: Sister Veronica fell on a piece of wood this morning and practically killed herself.

Flynn: Is she all right?

Sister A.: Oh, she’s fine.

Flynn: Her sight isn’t good, is it?

Sister A.: Her sight is fine. Nuns fall, you know.

Flynn: No, I didn’t know that.

Sister A.: It’s the habit. It catches us more often than not. What with our being in black and white, and so prone to falling, we are more like dominoes than anything else.

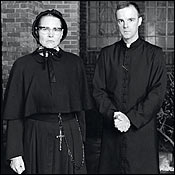

Now, take this tone that Shanley has staked out for himself—somewhere between teasing whimsy and darker implications—and project it onto the entire play, and you’ll grasp Shanley’s point that words hide as much as they reveal and can be interpreted in too many ways to afford us any certainties. Add to this superb performances: the incomparable Cherry Jones’s Sister Aloysius, perfectly poised between pernicious percipience and touching deludedness; the amazing Brían F. O’Byrne’s Flynn, whose bluff outspokenness in sermon as well as conversation may be more artful than artless; the adorable Heather Goldenhersh, whose Sister James is as blithely bubbly as vulnerably fragile; and the expert Adriane Lenox, whose Mrs. Muller makes her relatively few lines resonate throughout. Visualize this amid John Lee Beatty’s masterly scenery, and you have a theatrical experience it would be sinful to miss.

Doubt

by John Patrick Shanley.

Directed By Doug Hughes.

Manhattan Theatre Club. At New York City Center Stage I.