What a nice thing is Encores! Great to look forward to thrice a year and almost as good to look at each time. It means that three deserving old musicals will be revived over the season for five performances each, with several big-time performers who wouldn’t be available for a longer run and some new or newish talents whom it is a joy to welcome at the start of their careers. The latest trio of shows was perhaps a bit more uneven than usual but still well worth a smile and salute.

Under the artistic directorship of Kathleen Marshall and musical direction of Rob Fisher, this season began with the Rodgers & Hart Babes in Arms. Not only were there glittering songs in this 1937 work (movie version 1939), not only were there cherishable old and new faces on view, but here also was the fountainhead of the genre in which starry-eyed kids band together to put on a show within a show and emerge as a seasoned Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland & Co. There were fresh breezes from the past in Hans Spialek’s orchestrations, in the dramatic importance of a narrative ballet sequence (originally choreographed by Balanchine and worthily reimagined by Miss Marshall), in lilac-scented whiffs of FDR’s America reviving after war and depression. Race issues and red-baiting added color to the mix.

How pleasant to meet again old favorites such as Priscilla Lopez, Thommie Walsh, Donna McKechnie, and Don Correia; how heartening to encounter new ones in Matt McGrath, Michael McCormick, and the irresistible child tap dancer Cartier Anthony Williams. Most astonishing was Erin Dilly, a charmer recently wasted on the tour of Beauty and the Beast, when we badly need her in a major new Broadway musical.

Next came Ziegfeld Follies of 1936, a revue rather than the customary musical, with songs by Ira Gershwin and Vernon Duke and sketches by David Freeman and Gershwin. I don’t know whether sketches automatically date, but these certainly did despite the good efforts of Kevin Chamberlin and especially Stanley Bojarski, who also had to contend with Mary Testa, who makes going over the top indistinguishable from sinking below the bottom. Nor was Peter Scolari quite up to snuff, notably in the magnificent “I Can’t Get Started.”

There were, however, delectable contributions from the Specialty Trio: the brothers Bob and Jim Walton framing the picture-perfect Karen Ziemba. The playbill begged for comparison by listing the principals as “Christine Ebersole in the roles originated by Eve Arden,” “Stephanie Pope in the roles originated by Josephine Baker,” etc. Some, like Miss Ebersole and Howard McGillin, valiantly survived the hazardous comparisons; Miss Pope at least came within eye- and earshot; others lagged well behind.

The unforgettable revelation was Britain’s Ruthie Henshall in the Gertrude Niesen roles. A performer of pleasing but not sensational aspect, she entered from the wings, took a few steps centerward, and stopped (along with the spectators’ hearts), making the stage and auditorium her private property. Like some sort of human vortex, she drew us all into herself. Then she sang that great, underappreciated Gershwin-Duke song “Words Without Music,” and went from heart-stopper to showstopper as voice, stance, and expression merged into pure triple crème.

Hail also to the joint choreography of Thommie Walsh and Christopher Wheeldon; to the dancers, among whom Jock Soto stood out; and to parts of Mark Waldrop’s staging. Yet a show that originally featured the famed Ziegfeld girls and costumes could not fully be evoked here by a few fancy chapeaux.

Finally, we got Do Re Mi, a musical with a serviceable Garson Kanin book and enchanting score by Betty Comden, Adolph Green, and Jule Styne. It is the story of Hubie Cram, a small-time operator who can get his hand on some potentially lucrative jukeboxes if his shady pals will stake him, which they reluctantly do. They are up against the shrewd record-business tycoon and womanizer John Henry Wheeler, who promptly falls for their chief find, the singing waitress Tilda Mullen, as she does for him, and may steal her away. Meanwhile, Hubie tries to elude his long-suffering wife, whom he all but stands up on their wedding anniversaries and keeps mendaciously promising to whirl about a nightclub dance floor.

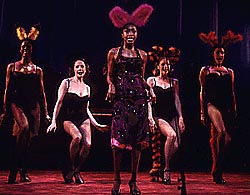

It is a sweetly silly story that lends itself to some choice horseplay, inventively directed by John Rando from a concert adaptation by David Ives. The production managed to transport what was essentially a staged reading gloriously close to a full-scale mounting. Supporting roles were brimmingly filled by Lewis J. Stadlen, Lee Wilkof, Stephen DeRosa, and a particularly funny Michael Mulheren, with added tidbits from Tovah Feldshuh, Marilyn Cooper, and Gerry Vichi. Randy Graff is a touching but perhaps overrefined Mrs. Cram, Brian Stokes Mitchell a dapper and debonair John Henry, and Heather Headley a capable if not exactly fetching Tilda.

But the show really belongs to Nathan Lane, whose Hubie sings, dances, and acts consummately, and mugs even better than that. His winks, sashayings, and lightsome chubbiness are prodigious: Lane may yet be the first one to go ballooning around the globe without a partner or even a balloon. This time it was Paul Gemignani conducting expertly, with fine contributions from John Lee Beatty (set), David C. Woolard (costumes), and Ken Billington (lights). Randy Skinner’s routine choreography was at least executed with enthusiasm.