If it’s true that God invented whiskey to keep the Irish from ruling the world, might it also be true that He invented plays so they could cope with the ensuing disappointment? Theater has given Irish writers an ideal venue for expounding upon their woes: dispossession, family terror, whiskey. Ironically, their native genius for storytelling has meant that—in modern theater, at least—the Irish actually do rule the world.

A Touch of the Poet, by American cousin Eugene O’Neill, doesn’t rank among the best works of the motherland’s best playwrights. Still, even in an undistinguished production, like the one it’s currently getting from the Roundabout, its unique virtues almost make it a great play just the same. In drawing the story’s marvelously contradictory hero, O’Neill has distilled themes of Irish drama to something like their pure essence and lent to them a sophisticated heartbreak all his own.

With his fine manners, fondness for Byron, and carefully submerged brogue, Cornelius Melody seems quite the gentleman. If you asked him, or if you didn’t, Melody would tell you that he’d been born in a castle on a vast Irish estate, only to be disenfranchised. Now, in the shabby New England inn that sustains wife Nora and daughter Sara (both of whom he considers despicable Irish swine), Melody will generously recall his youthful battlefield exploits. He has a fine capacity for waxing poetic about these glories, particularly if by “poetic” you mean “untrue.” His father, for instance, wasn’t remotely noble; he acquired his castle through unflagging avarice.

O’Neill’s story is vivid, but it’s not original. Melody bears an uncanny likeness to another self-denying, fantasy-swollen Irish adventurer, Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon. Yet O’Neill grants his hero—or, more precisely, inflicts upon him—a quality lacking in Lyndon and other predecessors: a piercing self-awareness. It’s one of the most insightful strokes the playwright ever made.

Melody appears to subscribe completely to his deluded view of his past and blinkered view of his present. When a wealthy young man falls for Sara, for instance, he condescends to the boy’s family when he ought to be lavishing them with thanks. Yet beneath his bluster, he knows full well that he lives on a rickety rope bridge of lies. “So may you go on fooling yourselves that I am fooled in you,” he growls to the hangers-on who pretend to be impressed by his lordly airs. The self-knowledge tortures him.

Relief comes to Melody in the form of that old bugaboo, whiskey. When he’s drunk, which is often, he has an easier time believing his illusions—or “pipe dreams,” as another O’Neill hero puts it. But the consequences for his family are terrible. For Nora and Sara, there is no escape: Melody will punish them if they challenge his illusions and, perversely, punish them for their credulity if they don’t.

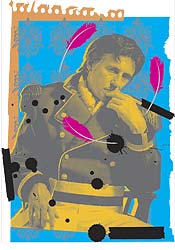

Amid Melody’s swirls of hostility, directed sometimes outside himself and sometimes within, Gabriel Byrne can’t always find his way. He conveys an elegant fake nobility, and proves demonically watchable during Melody’s late conversion to a kind of Fenian Mr. Hyde. But when the façade cracks and Melody turns suddenly ashamed or apologetic, we see little of the man’s soul.

Much of the play’s success hinges on the vision of himself reflected back to Melody by the women in his family; Doug Hughes’s production gets them half-right. As Sara, Emily Bergl shows poise but not style, bringing too much 2005 back to 1828. Dearbhla Molloy’s Nora, by contrast, is wonderful. From the steely set of her chin to the way she gingerly moves her sore feet around the room when she’s alone, it’s a deeply felt performance.

The fights with Nora underscore how, on some fundamental level, Melody’s story is a riddle about freedom. His delusions of nobility liberate him from the torment of daily life, but they’re a prison in their own right and turn him into a monster. Nora, by contrast, exercises her freedom to continue loving Melody in spite of his tyranny, and it makes her a kind of saint. Freedom does not mean license for O’Neill; it means choosing one set of hardships over another and attempting to live morally within them. Only a playwright from a tradition as steeped in loss and subjugation as the Irish could have written such unromantic things about freedom; only a creation as inspired as Cornelius Melody could bring their bitter contradictions to life.

This season’s production of O’Neill’s A Touch of the Poet has “Tony nominee” written all over it—but not “Tony winner.” Or so history would dictate: The original 1958 production, with Helen Hayes as Nora, was an also-ran for Best Play and Best Actress (Kim Stanley as daughter Sara). The next successful run, in 1977 with Jason Robards, lost out in the Best Revival and Best Actor categories. This year’s Cornelius, Gabriel Byrne, was nominated but didn’t win for O’Neill’s A Moon for the Misbegotten in 2000, and even the preceding contender for the part—Liam Neeson, who pulled out of this Poet production because of his movie schedule—was a Tony bridesmaid in 1993’s revival of Anna Christie. But at least that show won for Best Revival, and Neeson got an actual bride out of it—co-star (and co-nominee) Natasha Richardson.

A Touch of

the Poet

Eugene O’Neill.

Roundabout Theatre Company.

Studio 54.

Through January 29.