Great writers recognize the extraordinary in the ordinary. So do some lesser ones, as Terrence McNally does in Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. A waitress and a short-order cook have sex, bicker, and perhaps muddle through to something more lasting during a night when the moonlight through her Hell’s Kitchen window mingles with Debussy’s Clair de Lune on the radio. They have worked in the same hash house for some time before progressing to an ostensible one-night stand that may lead from the dark night of their souls to a perhaps brighter day.

Both have come through far more downs than ups. His include a bad marriage and some jail time; hers, dashed aspirations to the stage and much casually abrading sex. Her eyes are dilated with the vision of horrible sameness; his are narrowed in a die-hard optimism. Johnny finds portents of hope in the tiniest coincidences; Frankie’s gaze is often a few blinks ahead of tears. The pair manages some sustaining banter: hers mostly gallows, his largely gutter humor. He will make her love him in the face of her skepticism, disparagement, even her craving for a Western sandwich when he wants more lovemaking. And even if at a crucial point his organ does not rise to the occasion.

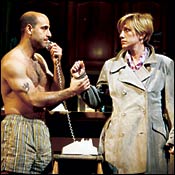

There is apt humor here and no less apt insight into the deviousnesses of the psyche. Above all, this two-character play, first seen in 1987, allows two fine actors to display their craft, their versatility, their humanity. It is absolutely right that Edie Falco and Stanley Tucci should look not the least bit glamorous or even actorish, with faces wearing nothing but experience by way of makeup. They brilliantly convey Johnny’s last-ditch bluster in comic-touching conflict with Frankie’s compulsive pessimism, as little flurries of laughter beat against an armor of deflation.No one can look more pervasively disillusioned than Edie Falco; nobody can, despite lapses into black hurt, summon up more bustling hopefulness than Stanley Tucci. Their expertly written and enacted thrashings make for Strindberg as rewritten by Neil Simon to nicely commercial effect. As tellingly directed by Joe Mantello on John Lee Beatty’s endearingly ramshackle set, and balm-bestowingly lighted by Brian MacDevitt, this slice of life sprinkled with all sorts of spicy toppings proves surprisingly nourishing.

The Apollo Theater may indeed be world-famous, but Harlem Song, the musical revue it commissioned from George C. Wolfe about its and Harlem’s history, will add barely an iota to its fame. The quantity of Wolfe’s ideas never was in question; only their quality. He can come up with lovely things like a one-woman show for Elaine Stritch or produce perfectly abysmal plays by … (you fill in the blank).

Despite its Apollonian name, what this theater specialized in was always the Dionysiac: the energy, the pizzazz begotten on the despair of social injustice. It provided performers with the shedding of any sense of discrimination or patronization, and allowed them to feel, rightly, famous and, in some instances, even world-famous. Like the love begotten on despair celebrated by lyric poets, this was feeling at its purest and strongest.

Harlem Song has no hunger behind it; it is motivated by its opposite. That does not mean that a show has to be in some way compensatory, but it stands to reason that to re-create an era of passionate ferment, satiety and self-satisfaction are a handicap. Or do you think that a 200-pound soprano can do justice to Puccini’s consumptive Mimi?

This is a sequence of musical numbers interspersed not with comedy skits but with solemn slide projections of events, usually serious, of Harlem history, and talking heads of elderly men and women reminiscing about the good old bad old days. What they say is not always particularly gripping but is spoken with authority and gusto, and the speakers should not go unidentified until the end.

The musical numbers suffer from Ken Roberson’s seamlessly derivative choreography, as also from Riccardo Hernández’s mediocre scenery and Paul Tazewell’s lushly pedestrian costumes. Only Jules Fisher and Peggy Eisenhauer’s lighting does interesting things, but you cannot come out humming the lighting. The nineteen songs are either standards or near-standards by respectable creators (although in unthrilling orchestrations by Daryl Waters) or new tunes by Waters and the show’s conductor, Zane Mark, with Wolfe lyrics, and definitely substandards.

The performers, including three quasi stars, are less than charismatic, and only a supporting player, Rosa Curry, caught my full attention. The worst thing is having disturbing historical slides cheapened by surrounding not-so-live live action. Even Japanese tourists on their Sunday gospel rounds are likely to turn up their noses at this schlock.

After so many hits, the law of averages demanded a clinker from the Kennedy Center’s Sondheim Celebration, and got it with A Little Night Music. Mark Brokaw, a fine play director, has less experience with musicals; John Carrafa’s campy choreography proves unsuited here (how one misses Patricia Birch’s charming dances for the 1973 Broadway premiere), and the gifted Derek McLane for once delivers an uninspired set design of large, flat, mushroomlike autumn trees that accord ill with the story’s summer setting.

But the main problem is the casting. John Dossett’s Egerman is a supporting player falling short of a lead – the lawyer’s deliciously deflatable comic pompousness goes by the board; as the glamorous actress Desiree, Blair Brown exhibits a blowsy bloat verging on frumpiness. As her formidable mother, Barbara Bryne offers touring-company stuff. Sarah Uriarte Berry, as the child-wife, is more 12 than 18, whereas Kristen Bell, as the 14-year-old Fredrika, is much too mature and colorless. As the ferocious Carl-Magnus, Douglas Sills sings well but acts a blustering pushover; similarly well-sung, the Petra of Natascia Diaz is nowhere near sexy enough. Danny Gurwin provides a credible Henrik, and Randy Graff, as the unloved and sardonic Charlotte, is, as always, splendid. Bitter sarcasms drip from her tongue with the sweetness and smoothness of honey.

Especially annoying is the poorly choreographed chorus of five, also unwinningly cast, with one dumpy, croaking matron particularly painful. Jonathan Tunick’s orchestrations remain masterly, and some of Michael Krass’s costumes score. But Sondheim’s infectious score (if not Hugh Wheeler’s book, a series of opportunities missed or ignored from Ingmar Bergman’s dazzling Smiles of a Summer Night) surely deserved a less stumbling production.

Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune

Revival of the play by Terrence McNally, directed by Joe Mantello; starring Stanley Tucci and Edie Falco.

Harlem Song

Historical revue conceived and staged by George C. Wolfe.

Sondheim Celebration

Revival of A Little Night Music, at the Kennedy Center.