Epistolary theater is an iffy business, correspondence being by definition a nondramatic activity. Further, Kathrine Kressmann Taylor’s epistolary novella, Address Unknown (1938–39), from which the play is drawn, was hot stuff at the time of Hitler’s rise, but rather passé today. It also depends too much on an O. Henry–ish final twist, which, like a joke’s punch line, is a narrative rather than theatrical device.

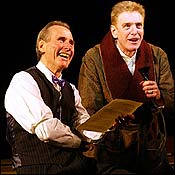

The play tells how Schulse, the Aryan partner in a San Francisco art gallery, relocates to his native Germany for his son’s education, and how the remaining Jewish partner, Eisenstein, indirectly but tragically affected by Schulse’s progressive Nazification, devises an ingenious revenge. William Atherton, who made his acting debut in 1970, has aged remarkably well, but his Nazi acting style for Schulse (ominously glazed stares, portentously singsong delivery), rather less so. As Eisenstein, Jim Dale is, as always, impeccable, although his British accent doesn’t mesh with Atherton’s American. Frank Dunlop’s staging tries everything possible to infuse movement and variety, but letter-perfect is not stage-viable.

Even the title cheats. The address is not unknown, the addressee is, but “addressee” would not click on a marquee.

Molière, playing Argan, the hypochondriac hero of The Imaginary Invalid, died just after the play’s fourth performance. At the first guest appearance by the Comédie-Française at BAM, I somehow survived, boredom being less lethal than lung disease. At fault was not the play but the long decline of the venerable C-F into something more institution than theater. It has tried to modernize the classics, but without attracting the acting talent it once boasted, or preserving its famed grand style. That style was admittedly rhetorical and overeuphoniously declamatory, but it was also a link to the past without precluding individual talent’s rising above the conventions. e Malade imaginaire is in prose, bereft of orotund Alexandrines, and the striving here for realism—down to the realistically muted period lighting—further impedes what was once the inspired artifice of the House of Molière’s heyday.

Claude Stratz’s direction, though at times too recherché, is not the real culprit, nor is the arguable excess or shortfall in production design. Rather, it comes down to the humdrum performances, save that of Muriel Mayette in the admittedly plummiest role, the shrewdly manipulative maid, Toinette. Some flaws are flagrant. The comic scene in which the lover Cléante, pretending to be a music master, and his beloved Angélique, as his pupil, enact a declaration of love under the purblind eyes of her father, Argan, falls flat with the unsensual affectlessness of Eric Ruf and Julie Sicard as the chemistryless lovers.

Alain Pralon’s Argan was a triumph of routine over bravura, and Alain Lenglet’s raisonneur, Béralde, made the voice of reason vapid.

The commedia dell’arte interludes were sensibly shortened and decently managed, even if hardest for sophisticated spectators to swallow. In the end, the French wordplay translated poorly into English, especially in surtitles that tended all along to come crucial seconds too late, thus leaving non-Francophone theatergoers stranded.

Lightning doesn’t strike twice: Don’t look for another Intimate Apparel in Lynn Nottage’s Fabulation or, the Re-education of Undine. This is the fable of Sharona, sharp enough to use an education way beyond that of her impoverished black Brooklyn background to reinvent herself as Undine and start a “boutique PR firm catering to the vanity and confusion of the African-American nouveau riche.” But at the height of her spurious prosperity, she marries an Argentine playboy, Hervé (why the French moniker?), who absconds with every nickel she has. Fallen to the bottom financially, socially, and emotionally, she gradually pulls herself up, partly by returning to her roots, partly through a series of painful misadventures that teach her valuable lessons, and finally through the love of a simple but good white man, Guy, who will even be a fine parent for the unwanted baby Hervé has fathered on her.

Problems? A rather far-fetched plot despite some racy incidents and savvy dialogue; a basically unsympathetic heroine whose happy conversion seems a deus ex machina; inferior production values in the constricted upstairs space of Playwrights Horizons; pedestrian direction; and, above all, an undistinguished supporting cast. As Undine, Charlayne Woodard is competent, although she overacts in Act One and cannot sufficiently engage our sympathy in Act Two.

“The knowledge that this claptrap is available in 31 languages ceases to be of much comfort.”

There are also troubling inconsistencies: Undine’s likable grandma shuttles between improbably literary and lowdown black English, and has her entire family fooled into believing her heroin addiction is merely diabetes. Maybe a Viola Davis and a Daniel Sullivan could have ratcheted up Fabulation; as is, it is far from fabulous.

The Norwegian Jon Fosse, poet and novelist, is also a playwright translated into 30 languages and performed everywhere from Taiwan to Serbia, from Iran to Chile. Only now, as translated and directed by Sarah Cameron Sunde, does a work of his, Night Sings Its Songs, reach us. This play about the near-breakup of an impossible marriage in the course of an agonizing night, to the accompaniment of an infant’s puling (presumably the titular songs of the night), is all clichéd language, trite bickerings, and banalities repeated verbatim. The phrase “I can’t handle it” alone must recur a good 30 times in this short but endless play, and after a while even the knowledge that this claptrap is available in 31 languages ceases to be of much comfort.

An unpublished writer (no name) mostly lies on a couch, reading what seems to be his only book. His wife (no name) expostulates with him in platitudinous jeremiads, written in a kind of free verse. There are Pinterian pauses, and occasionally she looks after the crying baby. By way of action, she finally goes out with a girlfriend and comes back late with a boyfriend, threatening to leave with him, but doesn’t. Throughout, the commonplaces are punctuated with the word “yah,” sometimes “yah-yah,” which, Sunde informs us, can mean “yes” and thirteen other things. The remaining words, unfortunately, have only one other meaning: tripe.

Of five actors, only the Norwegian Anna Guttormsgaard gives a performance, in excellent English, as the wife. As the husband, Louis Cancelmi actually manages to muck up silence and inertia, what with a steady expression midway between bovine and hangdog. I kept awake by counting the “yahs,” but, weak in mathematics, had to give up.