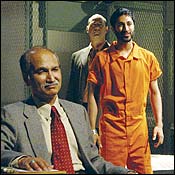

The culture project, which gave us the valuable prison documentary The Exonerated, now offers Guantánamo: “Honor Bound to Defend Freedom,” about British citizens detained at Guantánamo and the injustice and brutality prevailing there. Compiled chiefly from interviews with former internees and their kin, it concentrates on five detainees of very different backgrounds, but alike in their appalling victimization. Other prisons and prisoners figure, as do politicians, lawyers, and journalists, including Donald Rumsfeld, ably impersonated by Robert Langdon Lloyd.

Political drama is a necessary form of theater, as the ancient Greeks already knew. But it does present the major problem of occupying an uneasy middle ground between melodrama and the lecture hall: violence and torture on the one hand, sedentary palaver on the other. Moreover, the two hours’ duration (including intermission) of Guantánamo is both too short to cover all aspects of the problem and too long for audiences impatient with so much talk and minimal action: Chairs and cots can constrain dramatic development. Ultimately, too, excess worthiness can be as anesthetizing as excessive wordiness.

“I cannot promise a good time at Guantánamo, but I do consider the time spent there good for you.”

Still, it is needful to be reminded that the United States and Britain can be just as unjust, as inhuman, as our most despised and detested enemies. And under the joint direction of Nicolas Kent (at whose London Tricycle Theatre the show originated) and Sacha Wares, physically of necessity static but emotionally moving, a deserving dozen actors perform with unexaggerated intensity and whatever humor can be squeezed out of horrid circumstances.

Several performers are double cast, yet succeed, without benefit of makeup, to be convincingly different, and all, regardless of nationality, manage their accents commendably (the dialect coach, Stephen Gabis, merits mention). If I name Andrew Stewart-Jones and Steven Crossley, I do so only as first among equals. Miriam Buether’s prison set is suitably forbidding. I cannot promise you a good time at Guantánamo, but I do consider the time spent there good for you.

The blankest of dramatic blank-verse lines occurs in a 1730 play by James Thomson: “O Sophonisba! Sophonisba, O!” Unfortunately, this does not scan when Sophonisba is replaced by Susannah, which otherwise might be a fair comment on Susannah York’s solo outing with The Loves of Shakespeare’s Women.

Inspired, the actress and sometime writer says, by John Gielgud’s sovereign Ages of Man, it is a short but overlong compilation of speeches by women from Shakespeare’s plays; though some of these speeches are compounded from several, quite a few have little to do with love, and many feel uncomfortably stranded out of context.

York was one of the loveliest screen and stage presences of the sixties and seventies—a strawberry-and-Devonshire-cream beauty to take your breath away. She has come to Shakespeare but lately and sparsely. Now even her famously lambent locks seem withered—not by age but by a Draconian hairdo. Her voice is as sexy as ever, yet, for such a small venue as the Blue Heron Arts Center, often too loud, and sometimes curiously strangulated. Above all, save as mistresses Ford and Page back-to-back, she struck me as rather lacking in variety and that easeful connivance with the audience postulated by solo turns.

In a 1987 letter to Irene Worth, Gielgud, York’s inspirer, wrote about a TV project well conceived, except for the role played by “God knows why, Susannah York, who is very ill cast in my opinion.” Here, too, despite three sonnets nicely spoken, she seems—in elegant white in the first half, striking red in the second—somehow misplaced. It is not that she does not intersperse recitation with amiable personal recollections, or that the uncredited discreet period music is unsuitable, but some needed magic remains offstage.