It is possible for theater to reach your brain and funny bone while bypassing that most important organ in between. It is equally possible for it to affect the heart most strongly of all. What matters most in the English theater is style; in America, notable exceptions notwithstanding, the emphasis is on story; concurrent revivals of Tom Stoppard’s Jumpers (a London hit in 1972; Broadway flop in 1974) and Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (a Broadway hit in 1959) bear this out to striking effect. The plays couldn’t be more different: Jumpers is a philosophical farce, Raisin an often comic drama.

What matters most in Raisin, about the Youngers, an African-American working-class family in Chicago, is whether they will emerge from a ghetto existence, and if so, how. What matters most in Stoppard is ideas and the language for expressing them.

The chief difference between a story play and a style play is between characters in action and character of discourse. In Raisin, the Youngers; two black boyfriends of the daughter, Beneatha; and a white functionary who tries to bribe the family into not settling in a white neighborhood speak the same everyday language. You care about these people and what will become of them.

Not so in Jumpers, where the focus or hocus-pocus is on language: tropes and epigrams, paradoxes and puns. Characters behave quirkily and arbitrarily because they are only mouthpieces for the author’s clever conceits, chess pieces in a game he plays with himself. Black and white are not races in conflict but opposing colors on a chessboard whose manipulator plays mostly for display. The protagonist is an obscure middle-aged professor of moral philosophy named George Moore, a namesake of the distinguished philosopher George Moore, author of Principia Ethica, with whom he is sometimes humiliatingly confused. He is struggling with a lecture, and has an essay collection to be called Language, Truth and God, a quest for a deity and transcendent values. His antagonist is the university’s vice-chancellor, Sir Archibald “Archie” Jumper, who holds doctorates in medicine, philosophy, literature, and law, plus diplomas in psychiatry and gymnastics, and is a perfect cad. His initials yield a clue: A. J. Ayer (later Sir Alfred Ayer) was the famous philosopher of the logical-positivist school, which held that good and bad were relative terms, expressive only of our conventional notions. His magnum opus was Language, Truth and Logic.

George is married to the much younger Dotty, a musical-comedy star who retired prematurely because of a nervous breakdown. She used to sing romantic songs of the June-moon variety, but now, with men actually on the moon, the romance is kaput. Worse yet, the British astronauts she watches on TV are called Captain Scott and Oates, and Scott, to make his damaged craft lighter, has abandoned Oates to die on the moon. Their names allude to the doomed Antarctic expedition led by Captain Scott, where Oates nobly sacrificed his life in a vain attempt to save Scott and his team. Names become grist for the facile Stoppard’s pessimistically satanic mill.

“Even in its most heated passages, Raisin is about real characters in genuine conflict. We can empathize with these problems.”

Archie Jumper induces his faculty of logical-positivist philosophers to become gymnasts (i.e., jumpers) performing acrobatic feats such as a human pyramid at Dotty’s boisterous party, where George’s secretary does a striptease on a swing. An unknown hand shoots the center man of the pyramid, Duncan McFee, professor of logic and, apparently, errant lover of the secretary. Dotty is stuck with the corpse. Hysterical, she is treated by Archie as physician, therapist, and, very likely, lover.

Who murdered McFee? Comical Inspector Bones bumblingly investigates even while courting Dotty, whose ardent fan he is, though suspecting her of murder. Jumpers proceeds along three levels: First, a murder mystery, which is never solved (something that is, to say the least, problematic). Second, a parodistic philosophical debate between George, fumbling seeker of the absolute, and Archie, cynically amoral relativist. Philosophy as a joke: Striving to refute the paradoxes of Zeno, that an arrow can never reach its target and that a hare cannot overtake a tortoise when moving half the remaining distance with each stride, George ineptly practices archery and keeps a rabbit and turtle as pets but undoes both. Third, a George-Dotty-Archie love triangle, reduced to an unresolved farce.

The trouble is that this three-level prestidigitation never achieves the desired interrelation. We get instead more or less cleverly excogitated, linguistically acrobatic flippancy, along with characters who bypass the heart and end up not mattering.

Not so in Raisin, which, while hardly a comedy, contains much humor. The central problem involves genuine moral choices. Lena, the Younger matriarch, gets a $10,000 premium from her deceased husband’s life insurance. She wants to use it to move her family from their roach-infested dump into a nice house for all, with enough left over to send bright daughter Beneatha to medical school, as well as to create a nest egg for son Walter Lee and his wife, Ruth, a hard-working domestic. But Walter, a chauffeur with big-time capitalist dreams, wants to use the money to buy a liquor store with two questionable partners.

Even in its most comedic passages, Raisin is about real characters in genuine conflict; Beneatha, too, faces a choice, between two very different suitors. We can empathize with these problems. To be sure, if Stoppard’s play were better (as some of his are), the difference might not matter so much. Hansberry’s play isn’t perfect either; it is not art, merely adroit boulevard drama that pushes all the right buttons.

The current productions of both plays tend to highlight their strengths and weaknesses without solving any inherent problems. Jumpers is gaudily overdirected by David Leveaux, with Vicki Mortimer’s set—part Art Deco, part techno-modern—tawdry and obtrusive. Dotty’s frequent changes of Nicky Gillibrand’s garish costumes don’t help either. Especially damaging is the George of Simon Russell Beale, the most charmless prominent actor of the anglophone stage, often unintelligible in his rattled-off, guttural delivery. But Essie Davis (Dotty), Nicky Henson (Archie), Nicholas Woodeson (Bones), John Rogan as a philosophical janitor, and Eliza Lumley as the secretary who swings but never speaks do very nicely, as do the acrobats and the onstage band.

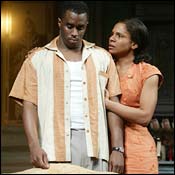

Under Kenny Leon’s meat-and-potatoes direction, all the principals in Raisin—Phylicia Rashad, Audra McDonald, Sanaa Lathan, and young Alexander Mitchell—do admirably. As for Sean Combs as Walter Lee, his eyes widen a bit too readily, his limbs are so loose as to threaten flying apart, and his face is curiously babyish. Still, he has genuine presence, and his emoting, except in a moment of utmost dejection, has alacrity—no diddling or puffery—and shows potential, if not quite yet heart.

Bombay Dreams? I don’t know about “… ay Dreams,” which may or may not allude to Hamlet’s “to dream, ay there’s the rub,” but “Bomb” it assuredly is. I’ll go further: It almost manages to make The Boy From Oz look good. The perpetrators, rashly ignoring Rudyard Kipling’s warning about East and West (never the twain shall meet), have concocted an olla podrida—a stew of oily East and putrid West clumsily combining the dregs of each. Worse than mindless, inept, and boring, it defeats any pejorative trying to sink to its level.

Yes, it may replicate on stage a Bollywood movie (although a film critic, I’ve never set foot in one), but what may work on a Bombay screen does not work on a Broadway stage, never mind Don Black’s desperate lyrics and Thomas Meehan’s doomed tinkering with Meera Syal’s clichéd book. The story—slum boy makes good as movie star, repudiates his untouchable granny and trannie friends, gets involved with the wrong woman and crowd, finally comes to his senses, returns to slum and grandmother, and marries the right girl—could give banality an even worse name. The music by A. R. Rahman—who besides selling 200 million albums worldwide is, the program tells us, “involved with several charitable organizations”—is itself a charity case, starved of originality and choking on triteness, and has successfully defied the efforts of four arrangers and orchestrators to make a silk purse of it.

Anthony Van Laast and Farah Khan’s choreography is an unholy mix of mudras and aerobics; Mark Thompson’s papier-mâché temples and inflated-elephant gods, plus a relentless parade of ever-more outré costumes (the show cost $14 million), is not so much conspicuous consumption as conspicuous presumption. As for the staging by Steven Pimlott—how do you direct a show that doesn’t know where it is going? In the cast, only Madhur Jaffrey is able to cook up a performance, and Anisha Nagarajan can at least sing sweetly; as for the hero, Akaash, the convulsive cavortings and strained vocalization of Manu Narayan are no better than his misleading-man looks. If you owe a present to your most hated relatives, you might want to buy them tickets to Bombay Dreams.