The usual trouble with adaptations is a lesser writer’s channeling a greater one’s work. Not so with Sweden’s Royal Dramatic Theatre’s mounting of Ibsen’s Ghosts. Here author and adapter—Ibsen and Ingmar Bergman—are of equal stature, and had assists from two Augusts: additions by or in the spirit of August Strindberg and a starring performance by Pernilla August. The result was august.

Ghosts has labored under two handicaps: being even talkier than other Ibsen masterpieces and being coerced by its era’s squeamishness into not naming the villain, syphilis, and thus turning into a giant circumlocution. Bergman has made many things more kinetic and more explicit—some would say overexplicit. But to the bringing of so much raw power and some added dimensions to the work, all I can say is skoal!

Omissions by Bergman, as of the lack of insurance making the orphanage fire a financial catastrophe, merely intensify the focus on what he most cares about: relationships either unrealized or realized with spiteful, desperate, or Oedipal undertones. Strong, too, are the increments, including a confrontation between Mrs. Alving, the sinned-against but not blameless wife and mother, and the proud but devious maid, Regine—both of them ambiguously involved with the doomed, syphilitic Oswald. He, in this version, is not the passive victim of paternal debauchery but a skulking, feral predator waiting to pounce. Regine’s putative father, the scheming hypocrite Engstrand (played as a grand scoundrel by Örjan Ramberg), and Regine herself (acted with a splendid mix of calculation and bluntness by the seductive Angela Kovács) get more of their due from Bergman-Strindberg than from Ibsen.

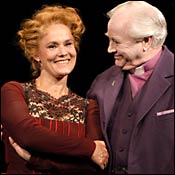

Jan Malmsjö, a fine actor, is miscast as Pastor Manders; he conveys the man’s cowardice and smarminess but not his appeal for Mrs. Alving. Jonas Malmsjö (Jan’s son) is an Oswald compelling in destruction and self-destruction, though his horror-film makeup does him no favor. Yet any Ghosts depends finally on Mrs. Alving, and Pernilla August juggles sexiness and guile, wit and pathos, with absolute mastery of both the grand line and the minute detail, earning our unqualified empathy.

The wide-open set, by Göran Wassberg, is ingenious: a huge, partitionless turntable that revolves into succinctly defined locations, leaving behind-the-scenes goings-on equally visible. Costumes, by Anna Bergman, and lighting, by Pierre Leveau, also score—like the piano score, by the for-once-persuasive Arvo Pärt, subtly played by Käbi Laretei. With this overwhelming farewell production, the 85-year-old Bergman goes out with a bang, not a whimper.

I have always considered Aeschylus and Sophocles great dramatic poets, but Euripides the first poetic dramatist able to command a modern stage. The National Actors Theatre has happily proved me wrong with Aeschylus’s The Persians (472 B.C.), which held my attention for its 80 propulsive minutes. Ellen McLaughlin’s version is both literate and actable, if a bit overinfused with contemporary antiwar relevance. Ethan McSweeny has turned the chorus into seven Persian counselors who mostly talk individually, and only rarely in concert or in repetitions. Just once in the end do they, effectively, sing. (Michael Roth has composed some persuasively archaic-sounding music.)

McSweeny gives them arresting moves and actions, and all speak well enough, although only Herb Foster distinguishes himself through looks, demeanor, and delivery. The minimal but inventive scenery, by James Noone, serves well, as do Jess Goldstein’s costumes (modern, but with an overlay of old Persian) and Kevin Adams’s unfussily resourceful lighting.

The Persians, though enemies, are treated fairly by the Athenian playwright, who himself once fought them at Marathon. Roberta Maxwell brings sovereign presence of speech and bearing to Atossa, widow of Darius and mother of Xerxes, but she might have been a little warmer in compassion for her defeated son. Michael Stuhlbarg is a suitably chastened Xerxes, and Len Cariou is properly ghostly as Darius’s minatory ghost. Good work by Brennan Brown as the shattered messenger who relates the terrible fiasco at Salamis, albeit with a rather too New Yorky accent. Altogether, American English lacks the melody that both classical Greek and modern British can stunningly supply.

With Bad Dates, Theresa Rebeck has written a thoroughly diverting, often touching, and ultimately wise solo comedy for the incomparable Julie White. Her Haley, the divorced mother of a teenage girl, decides to start dating again. For about 60 minutes of the play, she has nothing but hilariously bad luck with lamentable men, heightened by the perils of her running a restaurant for the Romanian mafia. But when disaster beckons, the last five minutes bring comic and existential relief.

Julie White has one of those knowing, lived-in faces, with which she achieves an inexhaustible expressivity both funny and endearing. No less enchantingly eloquent is what she does with her voice and body. In the pursuit of the right man, she keeps getting into and out of enough dresses for a runway model and has a running, ruminative relationship with countless pairs of shoes, about which Haley is adorably batty. John Benjamin Hickey’s direction, Derek McLane’s incisive set, and Mattie Ullrich’s canny costuming deserve unqualified praise. You will not want to miss this charming play; to miss White’s performance would be unforgivable.

If I had to choose between Chinese water torture and enduring almost any work by Marguerite Duras, I would probably pick the latter, despite a negligible difference. The vastly overrated Duras was a pentathlon champion, deftly hitting rock bottom in fiction, drama, film, politics, and honesty. In Savannah Bay, two women talk and talk—or pause and pose—without surcease. We don’t quite know who they are and can’t fathom what they are saying, still less why they bother. The set design ignores the author’s specifications—not that fidelity would have helped. The women drink tea, sing bits of a Piaf song, or sashay mutely around the stage. After 65 agonizing minutes, we are set thankfully free. In a pretentious program note, enough Duras obfuscation is on display to make the play itself mere supererogation.

Theater Listings

• Openings and Closings

• Broadway Shows

• Off-Broadway Shows

• Off-Off-Broadway