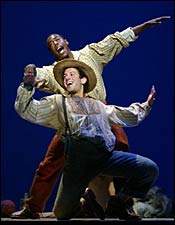

The current revival of the musical Big River is the brainchild of director and choreographer Jeff Calhoun, whose idea it was to blend deaf-mute and hearing actors in the same production, both using American Sign Language to convey words and lyrics in addition to those voiced by the hearing actors. In one case, actors of each kind were joined together in near-Siamese union, each performing in his own way. If this sounds redundant or confusing, so it was—at first. But one got used to it, at times even deriving enrichment from the procedure.

It is heartening to see challenged performers and spectators join the mainstream and demonstrate that certain previously ironclad boundaries can fall like the Berlin Wall, putting an end to—or at least a dent into—a form of ghettoization. You may not feel that this version of Big River is bigger than the original, but you won’t find it conspicuously smaller. Missed, to be sure, are Heidi Landesman’s munificent sets; still, with greater economy and no small ingenuity, these by Ray Klausen do very nicely indeed. Displayed by way of scenery and props all over the stage are the greatly enlarged covers, pages, and illustrations of the original edition of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, of which this is an inevitably shortened and simplified adaptation by Roger Miller (music and lyrics) and William Hauptman (book).

I mentioned enrichment. Thus when the nonspeaking Huck and speaking Jim affirm their newfound friendship’s superseding the master-and-slave relationship, they do so on the raft in the loveliest number, “Worlds Apart.” They face each other, and their signing, more excited than ever, turns into a ballet of arms and hands, a pantomime of two bodies groping their way toward oneness, and perhaps even a kind of secular prayer. Supporting and supported by the melody and lyrics, this becomes exultant and exalting.

I don’t usually care for country-and-Western music, but this score wins me over—another barrier down. That Roger Miller, much better known for his nontheatrical works, died before he could do another musical strikes me as a substantial loss. All the more reason to rejoice in Calhoun’s lively and sensitive direction and idiomatically integrated but unhackneyed choreography, attesting to the show’s renewable durability in the right hands. Our unfamiliarity with most of the performers proves no diminishment. This co-production with the Roundabout Theatre and two other groups originated at Deaf West Theatre, whose pockets are rather less deep than the Mississippi, yet the acting ensemble is such as to earn my not mentioning any names: All are just fine.

And there is also the best kind of sentimental enrichment. The actor who plays Mark Twain and supplies the voice of Huck was the Huck of the 1985 original Broadway production. That adds a sense of continuity, of the child as father to the man, which is as near to immortality as those of us short of genius can hope to get.

Avenue Q is a puppet musical that takes off from, saucily spoofs, and cheekily de-kidifies Sesame Street. Several Sesame characters’ caricatures populate the godforsaken Avenue Q where the play and some of the characters are laid.

Princeton laments in song the uselessness of his just-acquired B.A. in English: Every apartment from Avenue A to P costing too much, he rents on Q, from the super, a young black woman with attitude who turns out to be Gary Coleman. Other live denizens—the fat, unemployed would-be comic, Brian, and his exaggeratedly Japanese therapist fiancée, Christmas Eve—sympathize with Princeton.

Even more sympathetic is the homely puppet Kate Monster, who falls for him. Less sympathetic are puppet roommates Rod, a buttoned-up suit of an investment banker and closet queen; and Nicky, a charming ne’er-do-well, who assures Rod in song about obliging him, “If I were gay (but I am not gay).” Other puppet characters are Trekkie Monster—whom the puppets’ creator (and one of the puppeteers), Rick Lyon, describes as “the love child of the Grinch and Chewbacca—a masturbator to Internet porn (song: “The Internet’s for Porn”); also Lucy T. Slut, the Mae West–ish knockoff of Miss Piggy; and the mean kindergarten teacher Lavinia Thistletwat, whose assistant-drudge Kate Monster is.

Princeton desperately seeks a purpose in life; Kate Monster needs money to start a school for monsters (a Monsterssori School, natch!); Christmas Eve, an unsuccessful therapist despite two M.A.’s, needs patients; Rod must find the guts to uncloset himself; Brian must commit to Christmas Eve—they finally have a Jewish wedding; and the two mischievous Bad Idea Bears, who make trouble for all, must reform, which, in a funny way, they eventually do. Out of such ingredients, we get an X-rated puppet show that has fun with racism (song: “Everyone’s a Little Bit Racist”), homosexuality, full frontal puppet nudity and sex, schadenfreude (song: “Schadenfreude”), obsession with porn, and other things that Sesame Street, from which some of these perpetrators graduated, couldn’t do.

The show is clever, but in a sophomoric way; one torch song begins, “There’s a fine fine line/ Between a lover and a friend,” and there’s an even finer fine line between smart and smart-ass. Yes, the puppets are funny; the live actors as well as the puppeteers who, in plain view, act along with their puppets are versatile and personable; and persiflage in song and dialogue skips along in blissful smuttiness. Thus the closeted Rob boasts about a (fictitious) Canadian, and therefore absent, girlfriend: “Her name is Alberta, / She lives in Vancouver. / She cooks like my mother / And sucks like a Hoover.” The creators are Robert Lopez, Jeff Marx, and Jeff Whitty, and it’s a moot question whether the show is too whitty or too jeff by half. The audience members at the preview I attended were ecstatic: The laughter and applause were barely distinguishable in decibels from a terrorist raid. They all seemed to be graduates of a Monsterssori School.

The characters of Avenue Q express their secret longings in a song entitled “I Wish I Could Go Back to College.” The authors and their director, Jason Moore, I assume, have no such problems: In their hearts and minds, they’re already there.

Theater Listings

• Openings and Closings

• Broadway Shows

• Off-Broadway Shows

• Off-Off-Broadway