In Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker, Mick, the brutal younger brother, accuses Davies, the shifty tramp whom Mick’s elder brother, Aston, has taken in: “Every word you speak is open to any number of interpretations.” This charge can as justly be leveled at Pinter, whose plays can mean anything, which the gullible mistake for everything. Others, like me, view them as being about nothing, despite a certain cleverness in dressing up nothing to look like something. But what good are clothes with no one to wear them?

Of course, a play can have levels of meaning, but then it must function on all of them. Mick, Aston, and Davies may briefly fascinate through weirdness, permutations, and illogic, but their basic, unsatisfying incredibility does not end up standing for much. You might deduce that selfishness (Davies) does not know where to stop, and that goodness (Aston) can be pushed only so far. Or that in a ruthless world only the demented are good. Or whatever. But how do we get to the symbolic level if the symbolizers are a broken-runged ladder? The Caretaker’s literal level would have us believe that in an apartment with Collyer brothers’ clutter and no food, a penniless tramp could survive for a fortnight. And that Aston, however kindly, would tolerate even for two weeks a rancorous, ranting, filthy, and foul-smelling bum who deprives him of sleep. To be sure, Davies, that monster of ingratitude and opportunism, and the randomly destructive Mick may be a composite self-portrait of Pinter, who misses no occasion to vilify the United States in speech and writing while cheerfully pocketing our dollars as a substantial part of his income.

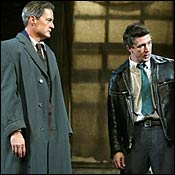

The Roundabout revival features a convincingly horrendous set by John Lee Beatty, aptly atmospheric costuming by Jane Greenwood, and condignly murky lighting by Peter Kaczorowski. Patrick Stewart, whose smugness is intolerable in subtle or sympathetic roles, is in his element as Davies, but, unlike Donald Pleasence, who created the part, allows a certain Shakespearean fruitiness to pop up in the tramp’s Cockney. Kyle MacLachlan is a suitably opaque Aston, although I have heard his big monologue delivered more penetrantly by Robert Shaw. Aidan Gillen is dizzyingly all that Mick should be. David Jones’s direction toils valiantly on behalf of the production, but cannot make a play out of a sow’s ear.

Paula Vogel deserves an A for effort with The Long Christmas Ride Home, but, unfortunately, a D for achievement. An attempt to amalgamate Western and Eastern theaters, drama and dance, story theater and conventional drama, puppetry and shadow theater of silhouettes on a backlighted canvas, the piece is as enterprising as it is, in the last analysis, unsatisfactory. Taking place in Washington, D.C., and San Francisco with intimations of its transoceanic neighbor, Japan, the play already fails by not making these places compellingly present. It concerns a family—Man, Woman, and their three (puppet) children, Rebecca, Stephen, and Claire—driving to grandmother’s house for Christmas, experiencing an intergenerational ruckus there, and driving home. En route, what with spousal bickering, Man nearly drives into an abyss (symbolism), and, daydreaming of his mistress, is about to slap his wife, when the action is interrupted by three flash- or flesh forwards, in which each of the puppet children, now human adults, comes to a sticky wicket shown in shadow play. Rebecca is locked out by her married male lover, Claire by her female lover now bedding a new girl, and Stephen by his male lover, similarly engaged with a new, younger man.

Each of these rejections is shown in live action and shadow play, and Stephen’s results in his seeking out a gay bar for unprotected sex (more shadow play). Courting and catching aids, he dies, and is resurrected in a suggestive dance number with a male dancer who, previously, as a swinging Unitarian minister, preached a sermon with projections of erotic ukiyo-e prints (Japanese for “floating world,” or world of pleasure). Stephen becomes a ghost haunting our world, but nothing much is made of this either. The play is a wedding of Thornton Wilder with Noh and Bunraku, and, like the marriage of Man and Woman, who are both actors and narrators (another failed union), a further conjugal fiasco.

Mark Brokaw is an able director, Mark Blum and Randy Graff (Man and Woman) are expert actors, and the adult versions of Basil Twist’s neat puppet children are tolerable human performers. All the designers—Neil Patel, Jess Goldstein, Mark McCullough, and Jan Hartley—are accomplished, as are David Van Tieghem’s East-Western music and John Carrafa’s choreography, acrobatically executed by Sean Palmer. There is much literal and figurative heavy breathing—not least on the part of language sweatily straining to be poetic—but the play’s world, instead of floating, collapses into hodgepodge.

The musical for children of all ages, provided they have no standards, Fame, now subtitled On 42nd Street (but for how long, one wonders), was originally performed in Swedish (Stockholm, 1993). As I watched it, bored out of my skull, I dearly wished it were still in Swedish. I would have been spared coping with the book of José Fernandez and lyrics of Jacques Levy, and would have been saddled only with the blatant music of Steve Margoshes and generic choreography of Lars Bethke. David De Silva, who conceived the movie version and advised the television show, is also behind this incarnation, if something so flesh- and bloodless can be called incarnate. A couple of the performers may deserve better; the rest fit, with unseemly seamlessness, into the proceedings.