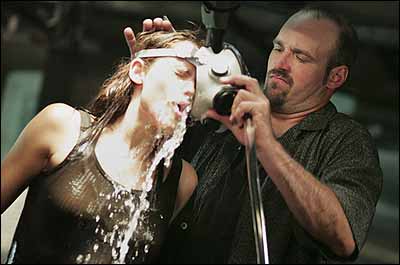

In the season opener of the spy show Alias, the heroine, Sydney Bristow, was captured and, in the delicate argot of espionage, “interrogated.” The villain shackled her to a chair, strapped a gas mask on her face, and hooked it up to a hose. Then he filled the mask with water—drowning her on dry land as she writhed helplessly.

It was a chilling scene, and not simply because of the violence itself. I realized I was watching a variant of “waterboarding,” the near-drowning torture the CIA has reportedly used on suspected terrorist detainees. I’d read about it in coverage of the Guantánamo hearings that very same morning. And that was hardly the first time a spy show had mimicked a real-life scandal. For the past three years, shows like Alias, 24, and MI-5 have provided a perverse mirror of the real-life response to terror: They’ve reflected, and sometimes eerily predicted, the rise of torture as a government policy.

Some of this is mere coincidence; stylized violence is the vocabulary of pop culture, and thrillers have always included torture in the mix: We have ways of making you talk, Mr. Bond. Still, the sheer preponderance of torture scenes on TV right now is unusual, and this crop of smart thrillers—of which I’m a big fan—began twisting the thumbscrews right after 9/11, three years before Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib hit the headlines. Alias launched nineteen days after the World Trade Center attacks, and the premiere episode included a scene where a torturer ripped out the heroine’s back teeth. The shows are unusually good at capturing the dark sensuality of torture: the Cartesian horror of being trapped in a vulnerable body, the sub-dom relationship of the torturer and his victim.

Most often in these shows it’s the villains being villainous, but regularly—and more interestingly—it’s the good guys in the tormentor’s seat. Sometimes they’re state agents desperate to coax out bomb codes; sometimes they’re CIA agents seeking revenge. In 24, the dark hero, Jack Bauer, has shot a suspect in the leg, squeezed bullet wounds, and withheld a bottle of heart-attack medicine. In Alias, the heroine is ethically pristine—she never tortures—but other CIA agents do. At the end of last season, Sydney’s love interest Vaughn discovered his wife was a double agent; he strung her up by her arms and pulled out the inevitable creepy bag of brushed-chrome surgical tools. It’s moments like this where the shows seem most directly to channel the political question of our time: What does it mean when our government resorts to torture?

Sometimes, the answer’s simple: It debases us. For sheer Cassandra-like precision, you can’t beat Tom Fontana’s movie Strip Search, which first aired on HBO last spring. It depicted a female U.S. interrogator sexually taunting an Arab detainee, a scenario that critics denounced as “silly and specious”—until a week later, when the Abu Ghraib abuses were exposed. According to Fontana, Strip Search was inspired by a direct reading of the Patriot Act in early 2002. As the creator of Oz and Homicide: Life on the Street, he knew the rules of interrogation, and he could see that they had moved the line. He was deeply troubled when the real-life abuses came forward. “You know what? I wish I had made it all up. I wish I had made it up in my twisted imagination, and that the world hadn’t caught up with me.”

I’ve wondered whether these shows treat suffering as entertainment or, worse, make government torturers seem heroic. Bauer may be a grim figure, but he’s portrayed with the sort of no-nonsense, take-charge style that Republicans revere. And with Abu Ghraib, many Americans simply snickered at the revelations; the very fact that the soldiers were cheerily e-mailing thumbs-up photos to friends back home indicated that they simply didn’t think this would bother anybody. But Bob Cochran, the co-creator of 24, argues that the torture in 24 doesn’t have that effect, and that the role of the show is to explore these debates. Even when his government characters inflict pain, they’re doing it in theoretically “ideal” circumstances: The terrorist really has the code, the bomb is really ticking. “In real life, you don’t have that certainty,” Cochran adds.

The truth is, there’s no way to simply praise or denounce these scenes. The scariest thing, after all, is not spy thrillers; it’s that our leaders adopt their rhetoric. When I watched Sydney Bristow tortured, I knew it was a schlocky Hollywood ploy, a way of making a premiere racier. But it was also an imaginative leap. When her mask fills up with water, you have to think about what waterboarding really means. We shouldn’t look to art as a guidepost for behavior. It’s more confusing than that: at once numbing us and pricking at us. But the fact that such shows cater to our creepier revenge fantasies isn’t reason to condemn them; for all their flash and gore, they can also be a step toward a moral debate.