What it has come to in our Brave New World Order is that only cops are forgiven for not tattling on each other. Behind their thin blue line, a code of silence is still considered to be a badge of honor, the last gasp of fraternal solidarity in a nation otherwise eager to unzip itself, to spill whatever beans will perk the prurient interest of the authorities or the media – in return for a lighter sentence, a bounty bonus, or a book contract. Assume the squealing position! To this contemptible new culture of blame-displacing songbirds, the DuPont- and Emmy Award- winning documentarian Ofra Bikel brings her unblinking camera, her tireless crossruff questions, her signature skepticism, and her civil-liberties fetish. The result is a ferocious installment of the PBS Frontline series called Snitch (Tuesday, January 12; 9 to 10:30 p.m.; Channel 13).

Just see what Orrin Hatched (though the unrepentant Republican senator from Utah was hardly the only member of Congress in 1986 to push through legislation requiring mandatory minimum sentences in every drug case brought to trial in a federal court and to tack on an even more hastily conceived “conspiracy” amendment that subjected the smallest guppy in the pond to the maximum penalties intended for the sharks). If a judge has no discretion, and neither does a jury, only the prosecutors get to play. Young men and women in the wrong place at the wrong time, who happen to be related to – or who even merely introduced the wrong people to – one another, face twenty years to life without possibility of parole. Their only alternative to heavy-duty hard time is to shop somebody (anybody) else. Not surprisingly, the sharks tend to shop the guppies.

In the past five years, Bikel tells us, nearly a third of all those doing time in federal drug-trafficking cases had sentences reduced because they informed on others. In Snitch, we meet a few who aren’t doing any time at all. Instead their girlfriends are, or their mothers, or a guy who drove the car to the site of the purchase, or someone they recall doing business with a decade ago. No evidence of “conspiracy” is necessary other than a stoolie’s say-so – not cash, not corroborative testimony, not even the drugs themselves.

All this may seem to you a niggle and a nag, maybe worth a twitch or two of that vestigial organ, the social conscience, but small beer in the larger picture of the great and glorious War on Drugs. You may even be inclined to disregard the self-interested vituperations of the defense attorneys Bikel talks to, at least till you meet Patrick Hallinan, the radical lawyer who defended the constitutional rights of one reputed drug kingpin, which kingpin then shopped Hallinan himself as a “conspirator.” (This didn’t work out so well for the government. Hallinan made mincemeat of its case in court and was acquitted, after which the prosecutors reneged on a promise of a lighter sentence for the kingpin!) You will also perhaps be unmoved by the qualms of district judges like Robert Sweet, and professors of constitutional law like Jonathon Turley, and even the appalled second thoughts of Eric Sterling, who was counsel to the chair of the House Subcommittee on Crime that formulated the 1986 law without bothering to conduct hearings in which they could have consulted concerned parties like the Bureau of Prisons.

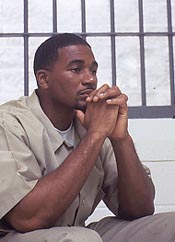

But you are not likely to remain unmoved once you’ve met Clarence Aaron, with no prior record and no material evidence against him, yet sentenced to three consecutive life terms on the testimony of childhood drug-dealing friends – all of whom had police-file priors – that he drove them to a buy. And Lulu May Smith, Joey Settembrino, Dorothy Gaines, and Ronald Rankins, all of whom Bikel also talks to, all of whom went to jail in someone else’s stead even when prosecutors felt bad about it, because they couldn’t or wouldn’t ante up alternative names. (In a Mobile, Alabama, case, it even seems that everybody had already named everybody else in town, so there was no one left to shop when they got around to the unluckiest of guppies.) Then there’s the father who was offered a deal: If he could make a drug buy from anyone, as part of a police sting, they’d go easy on his son, who’d been keeping bad company. Not to mention a mother who went to prison because she let her son hang around the house even though she must have known that he was up to no good. And we won’t even get into what I’m tempted to call the “unhush” money – the $100 million the FBI, the DEA, and Customs shell out each year to informants.

This is what television does best: personalize injustice. Put a face on, and listen to, the Clarence Aarons and Lulu May Smiths. And then do the same to senators like Orrin Hatch and Jeff Sessions and representatives like Bill McCollum. And meanwhile mix in the Hallinans and the Sweets. And finally ask us to choose for ourselves whom we believe, whom we trust. It’s what Bikel did to such devastating effect in her earlier Frontline documentaries on the satanic-ritual-abuse hysteria, and then again on the hypnotherapists who helped make that hysteria possible and plausible. And when it comes to the constitutional abuses of the Total War on Drugs, Bikel is only scratching the surface. For instance, she barely mentions another lovely weapon in the arsenal of the bullyboys – a “forfeiture law,” according to which the family of a suspected druggie can lose its house on the assumption that dirty deals were done there.

Once you’ve finished watching Snitch on Tuesday night, pick up a paperback copy of Dan Baum’s Smoke and Mirrors: The War on Drugs and the Politics of Failure. Read all about “loose” warrants, a weakened Miranda, and wiretaps on traditionally privileged conversations with doctors, lawyers, and clergy. About rico prosecutions that send college kids to prison for conspiring to introduce two people later caught peddling drugs. About legalized “no-knocks” and preventive detention. About warrantless searches of cars at roadblocks and schoolchildren’s lockers. About random urine tests; permission to open suitcases and first-class mail on the say-so of a barking dog; “courier profiles” that target Latinos and Nigerians; forced defecation, into airport waste-paper baskets, by anybody remotely resembling such a profile; the end of “exclusionary rules” on evidence gathered by heretofore illegal searches and seizures, based on an anonymous tip or a hunch. About revoking the passports of U.S. citizens caught with as little as a joint, and kicking first-time possession offenders and their families out of public housing, as well as canceling all federal benefits, grants, student loans, and mortgages.

It’s as if Andy Sipowicz were the chief justice of our Supreme Court.