Every Friday afternoon, round about 12:30, there’s a line of protesters in front of Union Square Cafe who come to raise their voices, if a little quietly, against atrocities that beggar their imagination. Not war overseas, but violence on our own shores—violence against ducks. Emboldened, if a little meekly, by pending legislation in the New York State Assembly, the activists gather to rail against the velvety duck-liver delicacy known as foie gras.

Outside the café, the weather isn’t so much a drizzle as a refreshing mist, nature’s reward to those who take up the Cause. Twenty-one people stand along 16th Street, facing the restaurant’s windows, as well-appointed patrons shuffle in for lunch. Along the curb, there are animal-rights advocates of every stripe: disaffected students, not-for-profit lawyers, a registered nurse on his day off. Some have arrived with non-poultry-related baggage. One woman tells me, rather improbably, that “everyone here also thinks about migrant workers.” Another is decrying the evils of dairy. But, in the main, the cadre is focused on the plight of the ducks. “This is just the result of French chefs with too much time on their hands,” says a dour screenplay editor. “Foie gras is not a staple—even if you’re French.”

Many brandish signs reading the truth about foie gras, which feature photos of ducks in their final agony: some lying dead with cornmeal clotted in their bills, others staring upward at a long metal tube about to be jammed down their supple throats, and still more splayed in blood.

Presiding over the ceremonies is an even-tempered woman named Anandah Carter. For the past nine months, while not doing voice-overs for PBS documentaries or radio work, she has coordinated the protests for a group called In Defense of Animals (IDA). At 32, she has large, empathetic eyes that scan the protest for any sign of overzealous campaigning. It’s her job to ensure that things don’t get too intense; she knows from experience that people are put off by radicals. “You have to know how to channel the energy,” she says, eyeing one hyperkinetic sign-shaker down the line. “We don’t want to shame people. They have to choose.”

Keeping legally clear of traffic outside Danny Meyer’s flagship restaurant, the protesters disseminate glossy leaflets titled “Cruelty Revealed.” The pamphlets declare that foie gras is “the diseased tissue of a tortured, sick animal,” that “birds have literally exploded” as a result of force-feeding, and repeat the words “vomit” and “feces” as often as possible.

The protest is anything but a spectacle, however. No tall man in a duck suit, his chest riven by burgundy cloth, waves his cotton wings; there are no unified chants. Only a few in the line seem to have met one another, so they spend as much time ogling other protesters as they do their targets—the people who have come, mostly in a state of blissful ignorance, to consume the offending item on the café’s menu. For there it is, listed so innocently alongside the mulligatawny soup and raviolini: the “seared foie gras with roasted asparagus, mâche, Sauternes vinaigrette and pistachio oil,” all at the blood-money cost of $16.

The sole bit of theatrics is offered up by a fiftyish nutritionist named Phyllis Roxland, who is holding a platter of one large clump of dough and a smaller, browner clump. The props are meant to represent duck livers—the larger of which is about the size of a human brain, illustrating how absurdly the organs are distended by the force-feeding process. Roxland has brought the items from home. The freakishly big “liver,” created for shock value, is shot through with specks of red and green. When I ask what the spots are, she says “blood and bile,” until I explain that I’m asking what they actually are, at which point she brightens and says, “I use ketchup for the blood—and the bile is made from some green beans I had.”

Even eight feet from the café’s door, many of the activists’ rebukes are barely audible to anyone entering the premises. Their gentle cries of “Choose compassion” can sound like “Shoes of fashion” to passersby. The loudest grievance of the day comes as Roxland scurries down the line, worriedly announcing, “I lost my livers!”

The protest, like any protest, is a war marked by lonely victories. The vast majority of patrons glance at the “torture” photos with a perplexed look. There is the 4-year-old girl dressed all in pink who stares at the signs without blinking, momentarily traumatized or fascinated; the purse-lipped matron who cryptically intones “I am aware”; the russet-haired lady who stops and tells the activists that she’s eaten foie gras many times, then breaks down and says, “I had no idea what was going on. You make me want to goddamn cry!” Most civilians employ the city’s no-eye-contact-with-anything-unusual technique or simply wave off the intruders. Some offer watery promises acceding to the group’s demand that patrons “ask the café to remove foie gras from its menu,” then vanish inside with all speed.

In the restaurant’s front window, seated at what must be the least-preferred table in the place, a fair-haired couple take small, unhappy bites of their salads. Their chairs are carefully angled away from the glass, but they occasionally look over their shoulders anyway and crinkle their noses, as if their Chardonnay is corked but they’re too embarrassed to complain.

Foie gras, the buttery, soul-melting, engorged duck liver that thrills the palates of Those Who Know, has become the focal point of nothing short of a culinary culture war. In the sixties, the stuff was sufficiently rare in America that it was something people mainly heard about in wistful discussions of French cuisine, an astonishing bonne bouche I experienced over there. Only in the past fifteen years, with the advent of production in the States, has foie gras become a medium for the great Manhattan chefs, from Jean-Georges to Daniel to Mario and all points radiating outward. It has become a symbolic cousin to cashmere and caviar, an emblem of wealth and refinement. Suddenly, New York is awash in the stuff. At Per Se, diners are offered sautéed foie gras with sunchokes, confiture of kumquats, garden tarragon, and a Banyuls-vinegar gastrique. At BLT Steak, one can indulge in a Kobe steak–and–foie gras sandwich. WD-50 has its own twist: foie gras–grapefruit–basil crumble with nori caramel. Braised, seared, even transformed into ice cream—foie gras is everywhere.

At the same time, the strife between those who abhor the stuff and those who adore it is coming to a flash point. Foie gras, depending on your point of view, is either a particularly brutal form of animal cruelty or a fête gastronomique that foodies would rather die for than surrender. In September, the state of California passed legislation to ban all sale and production by 2012, with similar bills introduced in Oregon, Illinois, and Massachusetts. Now, New York is on the front lines of the fight. A bill banning foie gras production passed out of the agricultural committee in the State Assembly on June 1. Though the law would stop short of halting sales, all production would end in ten years. Two of the three farms in the country that produce foie gras, Hudson Valley Foie Gras and a company known as B & B Poultry, are in upstate New York. Sixty percent of the foie gras produced in the U.S. comes from Hudson Valley. And Americans now buy 420 tons of the stuff; it is a $17.5 million business.

The controversy has arisen not over the mere slaughter of poultry but over the way foie gras is, and by definition must be, created. (Literally, the term means “fattened liver.”) Foie gras is that most Catholic of delicacies: paradise attained through suffering. The process generally involves a twelve-week stage in which ducks are allowed to roam free in a yard—then a four-week period of force-feeding, known as gavage. Two or three times a day, the birds have a tube jammed straight into their esophagi, at which point a few pounds of cornmeal are injected. Eventually, their livers expand to many times their normal size, at which point the birds are dispatched, and their innards served up to aficionados. It’s this method that makes foie gras so singularly rich and silky: By the time the ducks reach the end of the line, their livers consist of no less than 80 percent fat.

Protesters claim that, even by factory-farm standards, gavage is an abomination. They denounce it as a grueling process in which ducks are crippled, terrified, and beset with all manner of neurological and gastric diseases, including the actual rupturing of livers. Producers, on the other hand, say that gavage inflicts lower stress levels on ducks than the ducks would experience in the wild. One side describes the food as an elitist luxury born of abject cruelty, the other as a legitimate, if extravagant, lifestyle choice. Everyone calls everyone else a liar. Foie gras, in other words, is the new fur.

The Egyptians were force-feeding birds as far back as 5,000 years ago. In a tomb near Saqqara, one can see bas-reliefs of slaves jamming grain into a goose to make foie gras. The ancient Romans loved the stuff, too. In his “On Agriculture,” Cato the Elder wrote specific instructions that don’t vary much from modern-day techniques, advising producers to “cram twice a day.” Improbably enough, protests have a long history, as well. In the eleventh century, the French rabbi Rashi declared that Jews who force-fed birds would have some explaining to do in the afterlife.

Even outside the religious realm, there are broad philosophical questions at hand—many of which, as in any proper war, have no easy answer. Do ducks have souls? Do they suffer, really? When we kill for food, where is the line that separates humane conduct from barbarism?

Ariane Daguin, co-owner of D’Artagnan, the country’s leading distributor of foie gras, is not tortured by doubt. “Animals have no soul,” she says, in her rich Gascon accent. “God made ducks to have that liver—and He made it incredibly delicious! Why would it exist if not for us to enjoy it?”

Daguin does not come by her beliefs lightly. Her family has been producing foie gras continuously since the French Revolution. Further, she argues, the process is merely something ducks do naturally, to bulk up for migration. “No one invented the foie gras—the ducks did it themselves,” she says. “The liver is their cockpit for calories, and they need this when they are going to fly across the Mediterranean, when it is cold. So they have a natural propensity to extend and retract the liver. Besides, they have no gag reflex. It takes me pages to explain this, but all the protesters have to do is hold up a picture of a poor duck and people say, ‘If that were me, it would hurt.’ But this … this is the anthropomorphisme!” Daguin also invokes, and can produce, a French study appearing to demonstrate that ducks do not experience heightened stress from gavage. Judging from steady corticosterone levels, the study concluded that ducks actually worry more during the rearing process.

“God made ducks to have that liver—and He made it incredibly delicious!”says a foie gras purveyor. “Why would it exist if not for us to enjoy it?”

In a softer moment, Daguin concedes that abuse does occur in some farms’ production of foie gras—but adds that mishandling of poultry only renders bruised, unsuitable livers and is simply bad business. Still, she rues the misguided reasoning of her detractors. “There is a certain amount of cruelty in killing an animal to eat,” she says, “but there is also a certain amount of cruelty to pull a leek or carrot out of the earth to eat! Foie gras—this is the easy target. If these people wanted to start in the right place, they would outlaw the slaughter of cows in a kosher way, which they could never do here. The one time I saw a cow slaughtered that way, seeing it bleed for two hours, this was the one time I had to go outside and vomit.”

Daguin’s is the unspoken logic of many who have quietly resolved never to think about where meat comes from—those who will decry deer-hunting through a mouthful of venison. In the modern world, where humans increasingly see themselves as separate from nature, most carnivores are willfully blind to the direct line from butcher to brunch. To their way of thinking, in the Darwinian game, we’ve won. If ducks don’t want us to braise their livers, they would be wise to arm themselves.

For their part, the city’s chefs are extremely bashful about speaking on the record about foie gras. Having their names associated with images of poultry vomit evidently strikes them as less-than-stellar publicity. But, when granted anonymity, one of the most storied cooks in Manhattan is effusive. “Foie gras is very much like caviar,” says the Big Name. “The taste, the texture, the refined flavor. Oh! You can try to use any other kind of liver as a substitute and it will never, ever be the same. Foie gras has been a bliss for centuries—and it should remain so.”

This is the age of of absolute divisiveness. Just as there is red and there is blue, there is no middle ground on gavage. For every Ariane Daguin who embraces humans’ superiority over animals, there are those who are equally steadfast in claiming that the food chain isn’t so much a hierarchy as a horizontal structure, a world in which we can all just get along.

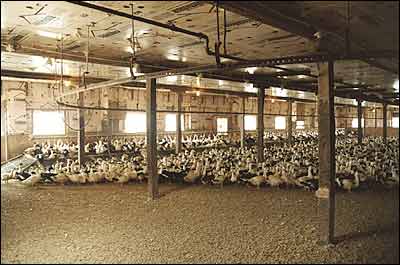

At another protest outside the Union Square Cafe, on another misty day earlier this month, Anandah Carter, the IDA coordinator, is appalled to hear of Daguin’s remarks. “No gag reflex?” she says, craning forward to telegraph contempt. “That’s one of the most insane justifications they use. These ducks’ livers are ten times their normal size! When they fly over the Mediterranean, they’re not ten times bigger. These ducks are living in cages—in feces.”

Jessica Morgan, a 26-year-old protester-dancer-Pilates-instructor, is still feeling her way along on these issues. I ask her if ducks have a soul. She ponders for a moment, then says, “Ducks do have a soul. They’re sentient beings. I honestly don’t know if vegetables have a soul. I don’t think so. But Buddhists say anything that flinches has a soul.”

I ask if, by that logic, humans would be wrong to perform medical experiments on ants. I’m trying to gauge where the activists draw the cruelty line—and, more to the point, why they aren’t protesting around the corner at McDonald’s, which is responsible for a cosmos of brutality that makes foie gras farms look like something out of those movies about the talking pig.

The answer comes from a young woman standing a few feet away who, until now, has conducted her vigil in silence. “Baby steps,” says the woman, an animal-behaviorism student named Michelle Redman. “Baby. Steps.” Redman has an indie-waif haircut, a silver piercing in her bottom lip, a Jamiroquai T-shirt, and a button that reads BUSH IS A POO POO HEAD. The suspicion muscle in the center of her brow is well developed, and she speaks every word in an angry staccato. “All fauna are equal,” she says. “A duck can’t add two plus two—but we can’t swim and fly and walk. It doesn’t mean they don’t have a soul. I believe in the food chain. But I also believe in peace. And this”—here, she juts a finger at one of the grotty bird photos—“this is not okay!”

Seasoned activists, of course, are more studied in their assertions. Bryan Pease—co-director of the San Diego–based Animal Protection and Rescue League, which filed the lawsuit that resulted in the bill that will banish foie gras from California—is particularly enraged by the stress analyses Daguin and others cite. “Yeah, I’m aware of that study, and they always refer to it,” he says. “But it was conducted by the foie gras industry, by a huge government infrastructure that wanted to show it isn’t inhumane. All you need to do is look at the injuries caused to ducks by force-feeding: the inability to walk, the filth, the incessant panting.”

Pease may not paint in the broad strokes of peace and war, but that doesn’t mean he’s unwilling to drop a bomb or two. “The foie gras issue is separate from whether people should eat meat,” he says. “These people are animal-torturing, psychotic extremists. They should be locked up.”

The man most detested by the animal-rights advocates, arguably the driving force in what made foie gras the sensation it is in America, is Michael Ginor.

At 41, Ginor is burly and built low to the ground, a fighter unmistakably. The eldest of three brothers, Ginor was born in Seattle, where his father was chief engineer for the Boeing 727 project. In younger days, he was a successful Wall Street bond trader, then (as the son of Israeli parents) he spent two years volunteering as a squad commander in the Israeli army, patrolling the Gaza Strip.

It was near Tel Aviv, 22 years ago, that Ginor first tasted foie gras. He recalls the event as “a magical experience,” the beginning of “a love story.” After returning to the States, he was stunned to sample foie gras from what was then America’s only producer, California’s Sonoma Valley—for this foie gras didn’t enrapture him the way overseas foie gras had. On a culinary mission, he sought out Ariane Daguin, who introduced him to an animal-science expert named Izzy Yanay. The two men founded Hudson Valley, keen to produce the high-quality foie gras Ginor had experienced abroad. While Yanay ran the agricultural side of things, Ginor took up with world-class chefs and traveled the globe, spreading the foie gras gospel. He likes to say that there is no major food festival on Earth in which he is not involved; in only the past six weeks, he has lectured on foie gras preparation in Singapore, South Africa, Vietnam, and Toledo, Ohio. His 1999 book, the 350-page Foie Gras: A Passion, won the Prix la Mazille for best culinary book in the world.

Oddly, unlike Ariane Daguin, Ginor makes no claim to being an absolutist on gavage. He says that, as he has entered his forties, the world is no longer so black-and-white to him, and people should be allowed to draw their own lines. “I wrestle with this,” he says equably. “I believe in karma. If I see an ant on the floor, I avoid it. I don’t needlessly take a life. I am not making the argument that ‘we’re humans and they’re ducks, so who the fuck cares?’ ”

What vexes Ginor, he says, is that the protesters are simply wrong in their most incendiary claims—mainly, that gavage induces disease. “We are not greedy farmers using leaky roofs and dirty conditions,” he says. “The problem of foie gras is one of imagery—the image of a tube being forced into a duck. That’s the one thing they go after, and it’s the one thing that can never change. No gavage, no foie gras! Seeing those pictures, you get this idea of a duck with a tube down its throat for a lifetime. In reality, it’s two or three times a day, for a few seconds.”

Bryan Pease openly calls Ginor a liar. Ginor insists there is no such thing as an “exploded liver”; Pease says his investigators have seen “truckfuls” of them at Hudson Valley. Pease also scoffs at Ginor’s claim that ducks, if released in the late stages of gavage, can recover. “These people are inducing a pathology,” Pease says. “The ducks don’t go back to normal. We’ve rescued ducks in those late stages, when they can no longer even walk, and they don’t survive.”

Never mind the larger questions of animal rights, Pease says. The foie gras industry simply crosses the line, even for the most avid beef eater. Still, as a devout vegan, he is well versed in the issues regarding, say, the value of a chimp’s life as compared with that of a human. “Though I guess it depends on which human you mean,” he jokes. “Are we talking about Michael Ginor?”

Ginor can’t resist a jab of his own. “Protesters create so much attention to foie gras that we’re selling more than ever,” he says, savoring the irony. “A chef I know in Cleveland told me that every time they have a protest, he sells more foie gras. I should fire my lobbyist and hire these guys.”

Ginor’s office is not upstate but on a leafy street in Great Neck; the walls are covered in awards, most of which are in the form of plates and platters. Lounging behind his stainless-steel desk, he gestures emphatically with his powerful right arm while the other lies fallow on the metal, as if his recent entry into the realm of gray has left half of him out of the conversation. Since it’s a Friday afternoon, Ginor has decided it’s proper to break out some cognac and torch up a Cuban Hoyo de Monterey cigar. “I am not a snob,” he says, his face half obscured by thick white smoke. “But when it comes to cigars, I can’t help myself. Dominicans just aren’t the same.”

On average, Hudson Valley produces some 5,000 ducks a week, or roughly 250,000 a year. Fattened livers are hardly the only product to be sold. There is no part of the duck that goes to waste. Feathers become down comforters. The breast of the foie gras duck, called “magret,” is an unusually rich and popular meat. Legs sell to become confit; fat gets rendered; skin is reborn as pâté; bones go to stock; and feet, testicles, tongues, bills, intestines, gizzards, and hearts are quickly peddled, mainly to Asian clientele. Izzy Yanay likes to say that they “sell everything but the quack.”

Ginor does not exasperate easily, but he won’t countenance accusations of savagery. Ten years ago, he says, he invited the ASPCA to Hudson Valley. The inspectors were given free run of the place, he says, and didn’t issue a single citation (that, despite the organization’s staunch opposition to foie gras production). The American Veterinary Association sent someone a month ago, Ginor says, and—though, here again, the AVA would never come within a light-year of endorsing foie gras—the man said he’d never seen such a well-run facility.

“The foie gras issue is separate from whether people should eat meat,” says an anti–foie gras activist. “These people are animal-torturing, psychotic extremists.”

“Our feeders are paid a bonus, did you know that?” Ginor asks. “Each gets 300 ducks at the beginning of the month, and at the end, we grade them on how many they bring back and the quality of the ducks’ livers. They treat those ducks like their children!”

That said, the image problems remain. Ginor says his farm’s mortality rate is about 3.5 percent (a fraction of that seen on general poultry farms), so basic math dictates that about 8,500 ducks a year won’t live to be slaughtered. “Of that number, it only takes four or five dead ducks in a barrel to look bad,” Ginor says.

While Ariane Daguin is agonizing over the possibility of a New York law banning production, Ginor is technically supporting it. Actually, it’s more than that—he and his lobbyists helped write it. Faced with the prospect of being hobbled by a new law every year, Ginor would rather have a decade to move his facilities to foie gras–friendly terrain. “I’m cooperating with this new bill because I can’t have a legislative guillotine hanging over my head year after year. I have 200 employees to think of. I know that sounds holier-than-thou, but …” If Hudson Valley is shut down, Ginor says, he has a fistful of options. Canadian commerce officials have come south to woo him. “We could also move parts of the operation to an Indian reservation, or to Connecticut, or North Carolina. Or I could just walk away, do something else.”

Only last week, anticipating passage of the new law, Ginor got word that the sponsor of the measure, Senator John Bonacic, had made an abrupt turnabout and now believed it would not pass during this session. But the news did little to console Ginor; as far as he knows, legislation that’s introduced in the very near future will ban production in less than the ten years for which he and his lobbyists have fought.

Ginor stares at the plates on his office walls, at the Venetian-glass urns of silver-painted duck eggs, at all the foodie memorabilia he has collected in the glory days of foie gras. He sees the writing on the wall. Even France—France! Consumer of 80 percent of all the foie gras on Earth, where even cabbies eat it—is coming under pressure from the European Community to close up shop. The day may soon come, Ginor fears, when foie gras is produced only in China and India. With nightfall, the window behind him has become as perfectly black as the perfect white of his cigar smoke. He shakes his head. “Funny thing,” he says. “I’m responsible for the founding and branding of Hudson Valley and popularizing foie gras in the United States. And now I am helping to write the law that could end it.”