By the time Jeanine tasted the white-asparagus soup with citrus ravioli and caviar, she was practically giddy. “I can’t believe how much I’m enjoying this,” she said. If anything, the best was yet to come, including the Maine lobster with saffron tapioca and Gewürztraminer, and especially the soy-glazed veal cheek with apple-jalapeño salad and celeriac purée—the most satisfying dish I’ve had in recent memory. But at that moment we reached some kind of hyperstimulated fugue state, the tastes of what we’d just eaten still vivid in our minds, while our expectations swelled for what was coming next. The well-lit room seemed to be suspended somewhere in midair against the backdrop of the nighttime foliage of the park to the east, hovering at the level of the fourth-floor “Restaurant Collection” of the Time Warner Center across the street, if not higher.

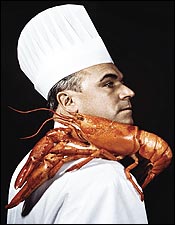

Robuchon’s in the house. Usher’s also in the house, at the bar here at Jean Georges with his mom, with that unmistakable low-rider hairline, drinking a cocktail of his own invention, Chambord and ginger ale. But his host, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, I have discovered, is only vaguely and intermittently cognizant of the showbiz luminaries who bedizen his restaurants. “He’s a big deal, yeah?” Jean-Georges asks me. “He’s here a lot, I think.” Meantime, Vongerichten is keeping an eye on Joël Robuchon, one of the last of the old-time Frog toqueheads, who retired from his eponymous Michelin three-star restaurant at 51 only to reemerge, seven years later, into a new culinary universe of multicultural menus and multinational empires that is to no small extent the creation of Franco-American prodigy Jean-Georges Vongerichten. “The guy’s a legend,” says Jean-Georges, who’s dressed in crisp kitchen whites finished off with black Prada trousers and loafers and looks like George Clooney crossed with a Renaissance putto.

“Il est très gentil, mon bon ami,” Robuchon says, hugging his host and beaming when Jean-Georges finally makes the trip out to his table. The Frenchman’s thinking of expanding to New York, opening a restaurant in the Four Seasons, and he wants to know what Jean-Georges thinks about the idea. No question—he’s come to the right guy. Along with Alain Ducasse, Vongerichten has pioneered the idea of a global franchise based on haute cuisine.

This week, he opens another restaurant, Perry St., his eighth in New York, on the ground floor of one of the three Richard Meier towers in the far West Village. He’s calling it a neighborhood place, partly to keep a lid on expectations and partly because he lives upstairs in a luminous box on the seventh floor. The last time Vongerichten opened a little neighborhood place, it was called JoJo, a unique blend of casual setting and ambitious, inventive cooking that spawned a hundred and one imitators.

It’s probably safe to say that in the past two decades, no single chef has had more influence on the way New Yorkers dine out—or on the way other chefs cook and other restaurants look. “He invented America’s answer to nouvelle cuisine,” says Mario Batali, who knows something about starting culinary trends. “When I first came to New York, his book Simple Cuisine was the holy grail for young chefs, and JoJo was the hottest ticket in town.” Before opening JoJo, the classically trained chef had reinvented haute cuisine at Lafayette in the Drake Hotel, substituting vegetable juices and infused oils for butter and cream sauces while introducing Asian ingredients like lemongrass and ginger into the classical vocabulary. Vongerichten’s fusion cuisine was the gastronomic equivalent of Blade Runner.

With the opening of Mercer Kitchen in 1998, Vongerichten created a new kind of fusion—a merger of cuisine and scene, a place where you might see Laurie Anderson sitting next to Jeffrey Steingarten. In 2003, his Richard Meier–designed Shanghai noodle factory, 66, thrilled the fashionable wing of his constituency while irritating some hard-core chowhounds.

Last year, he kept up his torrid pace—he opened four restaurants, including one in Shanghai and one in Houston, and was named Restaurateur of the Year by Bon Appétit—but his empire began to show cracks. When Spice Market got a quick three stars from interim New York Times critic Amanda Hesser, the triumph curdled slightly when it was pointed out that Hesser had been the beneficiary of a blurb from the chef for her book Cooking for Mr. Latte. Even Jean-Georges seemed surprised by the three-star review for his indoor rendition of Asian street food. “The rumor’s not true,” he says with an impish smile. “I never slept with her.” Like some complicated good-news-bad-news joke, the review also failed to mention Vongerichten’s consultant, Gray Kunz, exacerbating the friction between the two. (Kunz subsequently bailed.) And then came the lukewarm critical reception of V, his reinterpretation of the New York steakhouse in the Time Warner Center’s food court.

Frank Bruni, the Times’ then-brand-new restaurant critic, made V his first hit job, giving it a single star. Not that Bruni was alone: New York’s Adam Platt was similarly tepid in his assessment. The final blow was a damning account of Vongerichten’s recent evolution by veteran food writer and former Jean-Georges cheerleader Alan Richman in the year-end issue of GQ—an apostasy that was the food-world equivalent of Nietzsche’s turning on Wagner. Richman accused Vongerichten of selling out, devolving from culinary artist to franchise manager. While calling him “the most inventive and certainly one of the most beloved French chefs working in America,” Richman went on to trash all of his New York restaurants in their current incarnations.

The piece was a shock. Vongerichten admits he was crushed. “I went to bed for three days,” says the hyperactive chef. On the fourth day, he went to the doctor, as if convinced that the emotional blow must manifest itself physically. “He told me I was ridiculously healthy,” the chef says, sounding almost disappointed.

The backlash might seem inevitable, from the outside. The guy, after all, has had nothing but hits, and until recently he’s made it look easy. He’s rich: Prime Steakhouse in Las Vegas, just one corner of his empire, did $16 million in business last year. He’s earned not just one but two four-star ratings from the Times and won seven James Beard awards. He just moved into a beautiful apartment overlooking the Hudson in the most talked-about residential complex in the city, a project in which he was a partner. He has a beautiful young wife, former Jean Georges hostess Marja Allen, the mother of his 4-year old daughter, Chloe. He doesn’t seem tortured like Thomas Keller, nor wacky like David Bouley. What’s not to hate about someone this successful and seemingly well adjusted?

If he was ever complacent or distracted, he’s definitely not feeling that way now. One of his most likable qualities—and he is a very likable guy—is his willingness to take criticism to heart. He thinks of himself as a host, and he hates to see his guests unhappy. “Maybe I was stretched a little thin last year,” he says in his melodic, mumbling English, flipping an omelet in the spotless kitchen at Jean Georges while he watches two sous chefs plating an order. “I open four restaurants. But I love creating new things. It’s difficult to be creative once a restaurant’s open. People want the same dishes. For me, the creativity is in opening a new place and starting a new menu.”

Indeed, after spending time with the whirling dervish of a chef, who seems in many ways like a smart 12-year-old in need of Ritalin, I can’t quite imagine him confined to a single kitchen. He has a very hard time sitting still, though he flatly rejects the suggestion that he’s abandoned the stove. Lately, even as he’s been trying to save V and open his new place, he’s been toiling at the Jean Georges mother ship, tweaking and freshening the menu. He knows that Frank Bruni, midway through a revisionist tour of the city’s four-star temples, will hit Jean Georges soon. Vongerichten’s cred in the food world still depends on those four stars.

Vongerichten’s fiercest competitor, at least in the minds of aging foodies, is his younger self and memories of meals at Lafayette (don’t ask me, I wasn’t eating much in the eighties), the ultimate of which was a dinner in honor of Salvador Dalí, based on his cookbook Les Diners de Gala. The first course was a dish called Eyeball, made of foie gras in aspic, with a black truffle. The Breast of Venus was made from tripe and a carrot. Erection featured a rabbit sausage with bean sprouts for pubic hair. “Lafayette was a fantasy,” he says now. “It was the eighties. One time, I bought half a ton of black truffles and froze them.”

In fact, the Drake Hotel subsidized the restaurant, which was losing $50,000 to $60,000 a month. “You just couldn’t do that today,” says chef Kerry Simon, who worked in the Lafayette kitchen. Like so many other enterprises in 1987—including the federal government and nightclubbing stockbrokers who postponed sleep until their old age—Vongerichten’s fantasy kitchen was operating on the deficit-spending principle. But unlike most of his customers, the four-star chef wasn’t getting rich. In 1986, when he got three stars, he was making $450 a week. By 1990, when he decided to leave the restaurant, New York’s most celebrated chef was making $95,000 a year.

Now he’s making more than many investment bankers, presiding over an empire of eighteen restaurants and 2,200 employees. The 60-seat room on Perry Street might seem almost like an afterthought, but it clearly represents something important to the chef, a restatement of principles and a return to basics. “This is actually incredibly important to him,” says Lois Freedman, his former girlfriend and longtime business manager.

Perry St. is meant to be more civilized and grown-up than Spice Market, less formal than Jean Georges. The room, designed by Richard Meier protégé Thomas Juul-Hansen, is a cool, spare, Bauhaus-y oasis in soothing neutral tones—a Scandinavian blonde of a room. Vongerichten’s been describing the menu as New American, but world cuisine might be a better label (warm oil-poached hamachi, crunchy rabbit kanzuri). The room will please the fashionable wing of Vongerichten’s coalition—Anna Wintour and Michael Kors threw a party there recently—and in many ways the décor telegraphs the vivid minimalist appeal of the food. “Clean, pure, and simple,” intones Vongerichten, standing in the kitchen the day after returning from Bangkok, where he judged the Miss Universe pageant.

He and chef de cuisine Greg Brainin, who’s been with him for six years, were editing and fine-tuning the menu down in the kitchen. His ability to operate multiple kitchens is a function of his ability to inspire and maintain the loyalty of people like Brainin and Pierre Schutz, the executive chef at Vong, who has been with him since the Lafayette. Brainin works with a list of seasonal ingredients, a list of textures (“creamy,” “crunchy,” etc.), and a list of flavors (sweet, sour, bitter, hot …). Vongerichten seems to have a more instinctive approach. This afternoon, they’re both excited about their new immersion circulator—a piece of medical equipment repurposed to the task of low-temperature poaching, a method that previously required constant adjustment of the gas flame and the addition of ice cubes to maintain a consistent temperature. A couple of dishes are being designed around the new toy, including a poached rabbit.

I’d already watched him open one new restaurant this past winter in a nightclub-casino called 50 St. James, presumably lured by a lucrative contract from Planet Hollywood owner Robert Earl as well as a desire to reestablish a presence in London after closing Vong in 2002. Vongerichten went to London for a week with a team that included his culinary right-hand man, chef Daniel Del Vecchio; business partner Phil Suarez, the former movie producer and adman who has financed Vongerichten’s dreams since they opened JoJo together; Lois Freedman; and half a dozen other members of his team. He introduced the kitchen staff to five new dishes each day, culled from the 3,000-plus that Del Vecchio has stored in his laptop, each with instructions far more precise than anything in the average cookbook, many with hand-drawn illustrations by Vongerichten, all designed to ensure that eventually chef Shaun Gilmore, who worked with him at Vong, London, can deliver Vongerichten’s food from a Jean-Georges-less kitchen. On opening night, Vongerichten was furiously chopping, stirring, and plating, rallying the troops—“No, no, ze mince is too small, see, like zis”—sending out his famous egg caviar and spicy marinated tuna ribbons to the likes of Andrew Lloyd Webber, Kim Cattrall, and a Middle Eastern prince who’d just dropped a million pounds in the casino downstairs.

“This is my kind of food,” Jeanine said about the hamachi with fresh wasabi, yuzu, and green apple. “It’s so … clean.” So interested had she suddenly become that she insisted on sharing my sea-trout sashimi in trout eggs, dressed with lemon, dill, and horseradish. “Okay,” I said, “leave some for me.” Vongerichten continued to send out separate dishes, and we made a pact to share them equally. Fortunately, she got way too busy with her scallops and caramelized cauliflower with a caper-raisin emulsion to seriously deplete my char-grilled foie gras wonton with red papaya, passion fruit, and spiced red wine. I often get bored in the middle of a dish, in which case I don’t mind sharing, but that wasn’t the case here; just as I figured out the perfect ratio of wonton to papaya and passion fruit, it was gone. Was it love that compelled me to save her a bite, or was it the desire to get at her scallops?

“They’re touching the corners!” Vongerichten says, watching the wait staff being trained. “It drives me crazy.” His voice is calm, but he’s dead serious.

The opening of Perry St., while relying on the same well-oiled management team, is a more intimate and improvised affair. For one thing, all the dishes will be new. “I want every dish to be a ten,” Vongerichten says. Tasting with him a couple of weeks before the opening, I thought he was getting pretty close. They were working on seven dishes that day, starting with crab ravioli. Jean-Georges isn’t quite happy with the dashi emulsion that first dressed it. “Too Japanese,” says Freedman, who started out in the kitchen at Lafayette nineteen years ago. Vongerichten asks Brainin to whip up a broth of snap peas. “That’s it—the essence of summer,” he says when he sticks his nose in the green broth. “I want everything bright.”

The clean-pure-simple mantra is perfectly incarnated in the next dish, Japanese-snapper sashimi with lemon, olive oil, and crispy skin. It’s highlighted with tiny slivers of red finger pepper and texturized by the “crispy skin,” which is removed from the snapper, frozen, thinly shaved, rolled in corn flour and deep-fried for a few seconds, then sprinkled back on top of the cold sashimi. I could eat this every day. Possibly twice a day.

Lightness is the quality that Vongerichten seeks, an illusion of pure flavor without substance, which may be one reason he’s so popular among the Prada set. (“You cook the way you look,” being another motto of the lean, athletically toned chef.) The next appetizer up for consideration fails the lightness test. He’s been experimenting with a bacon-and-eggs concept, which has become a braised pork belly in a sweet-and-sour sauce with an egg poached for 40 minutes in the immersion circulator. When we sit down to try out the new dish upstairs, the egg’s pretty amazing—both yolk and white have almost the same custardy texture. The braised pork belly’s delicious but heavy—more Daniel Boulud than Jean-Georges.

“I can’t serve this as an appetizer,” says Vongerichten.

“I knew you’d say that,” Brainin says, then turns to me: “He’s afraid of pork as an appetizer.”

“Hey, I grew up with pigs,” says Vongerichten. “Maybe we’ll try this again in the winter.”

The egg, though, is so good they want to keep it and start over. “How about asparagus and shiitakes with the egg?” suggests Vongerichten. “The egg is like a hollandaise on top.”

“That’s good—earthy, grassy, and sulfury,” Brainin says.

Vongerichten nods thoughtfully, but he’s turned his attention to the new wait staff, who are being drilled by his front-of-the-house general, Denis Bouron, who has split the new staff into two groups, one group serving the other, running through the motions of an entire meal with empty plates and glasses. The chef watches the serving group move between kitchen and dining room. Something’s bothering him. The elegant, rail-thin Bouron drifts over, as if summoned telepathically. “They’re touching the corners,” Vongerichten says. “It drives me crazy.” He jumps up and demonstrates, walking around the room, touching the walls, touching the bar, touching the corners of the tables. “They’re touching the walls. We’ll have to repaint the fucking room every week.” His voice is relatively calm, and none of the wait staff can hear him. But he’s dead serious. “I’m a clean freak,” he says, almost apologetically. “At Lafayette,” says Freedman, “he used to clean the refrigerator for relaxation.”

Clean is practically Vongerichten’s favorite word (along with light). He could well have called the new restaurant A Clean, Well-Lighted Place. All of which may be a deep-seated reaction to coal dust, to its pervasiveness in his youth, and to the fact that he grew up with the understanding—or the fear, really—that he would take over the family coal business in Strasbourg.

While in London, Jean-Georges took me to the cultish St. John, where chef Fergus Henderson practices “nose-to-tail” cooking: slow-cooked pig parts, including the offal and bone marrow and chitterlings—the opposite of Vongerichten’s ethereal fusion fare. Henderson’s food carried Vongerichten back. “Look at this,” he says, as the waiter places a giant ham hock with cabbage in front of him. “This is what I grew up on in Alsace. It’s choucroute. I’d wake up every morning with the smell of cabbage and potatoes and pork.”

Vongerichten was raised in the riverside house his great-grandfather built in 1833. Working with his father as a young man, he grew to hate the family coal business. He was far more interested in his mother’s end of the operation, feeding some 40 employees every day. Recognizing her son’s precise palate, she came to rely on him to adjust the seasonings.

It didn’t occur to him that there was a career path there until after he was thrown out of technical school. On his 16th birthday, his parents took him to the three-star Auberge de l’Ill to celebrate. Jean-Georges was exhilarated by the meal and had an epiphany when chef Paul Haeberlin came over to the table. “I was amazed. I thought, This is it. This is what I want to do.” His mother promptly badgered Haeberlin into finding a place for the aspiring chef.

Vongerichten began an apprenticeship that lasted three years and included a stretch as chiens chef—cooking for the customers’ dogs. After a stint in the army, he managed to secure a spot in Louis Outhier’s three-star kitchen at l’Oasis, outside of Cannes. If Haeberlin’s kitchen was all about advanced preparation, Outhier’s was more about winging it. “Everything was done à la minute. He insisted on chopping everything fresh.” Outhier was also a fanatic for cleanliness and order, a trait he passed on to his young protégé, who already had an ingrained loathing of dirt and coal dust. It was in the sunny south that Vongerichten first learned about olive oil and fresh herbs, and he also modeled his personal style on the older chef, whom he remembers as “very elegant, beautifully dressed, very civilized—a bit of a playboy. He teach me about clothes and about women. He was kind of a father figure to me.” Vongerichten’s own father didn’t speak to him for more than a year when the son announced he would not be joining the family business.

After a nine-month stint with Paul Bocuse, the famous Lyonnaise three-star chef, he got a call from Outhier, who had a lucrative contract with the Mandarin Oriental hotel chain, offering him a job in Bangkok. In November 1980, the 23-year-old Vongerichten took over a kitchen with a staff of twenty Thai cooks, none of whom spoke French. He took English lessons and struggled to train the staff. While Vongerichten was cooking classical French food, he was falling in love with the flavors of Thailand. “I was eating Thai food three meals a day; it was incredible. The dish that changed my life was tom yum kum. You start with a pot of water, add lemongrass, lime leaves, lime juice, coriander, mushrooms, and shrimp; ten minutes later, you have the most incredible, intense soup. Instead of boiling old bones for twenty hours the way I’d been doing.”

He stayed in Bangkok for two years, after which he moved on to Singapore, Hong Kong, and Osaka, delving into the local cuisine at each stop. He had his first sushi in Japan in 1984, initiating yet another love affair: In New York, he eats sushi two or three nights a week, often at Sushi Seki on First Avenue.

Given that he left home at such an early age and disappeared immediately into a kitchen, Vongerichten never had the opportunities to develop a taste for socializing. To this day, for all his celebrity, Vongerichten doesn’t seem entirely comfortable with New York high life; he recognizes its utility for business but does not enjoy it. He loves skiing, hang gliding, paragliding—anything fast and dangerous, according to wife Marja—but he claims that the best part of any vacation is returning to work. Although he will come out of the kitchen at Jean Georges to greet an important diner, he’s happiest back among his chefs with a pan in hand. “He doesn’t know how to chill,” says partner Phil Suarez. When I ask Freedman, who lived with Vongerichten for three years, who his best friend is, she looks puzzled: “That’s a good question.”

“His best friend,” Suarez says, “is the kitchen.”

To say he’s a workaholic is an understatement. Unlike some celebrity chefs, it seems, he’s not abandoning the stove so much as multiplying the number of stoves behind which he can toil.

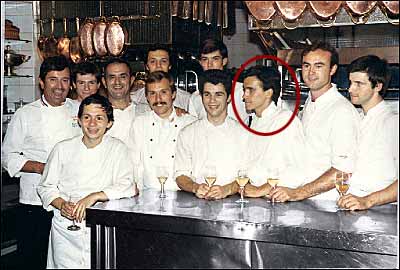

Vongerichten landed in New York in 1986. He was 28 years old, with a wife and two children in tow, and he had another assignment from Outhier—to start up a dining room for the Drake Hotel on Park Avenue and 56th Street. “I was doing his style of cooking,” he recalls. “It took two and a half hours to do the lunch. For the first six months, I didn’t leave the hotel. I was scared. I was a country boy. Then Gilbert le Coze”—who founded the fish palace Le Bernardin—“came in. He was the second chef I met. He took me to the Fulton Fish Market. I wasn’t happy with my fish. It was six days old.” Gilbert introduced him to the highly regarded wholesaler David Samuels of Blue Ribbon Fish Company, who refused to let him buy until Vongerichten invited him to the restaurant, and who remains his main supplier to this day.

Now, with a $2 million budget, Vongerichten is attempting to recapture JoJo’s simplicity at Perry St.

Not long after he discovered the fish market, early in 1987, Vongerichten visited Chinatown, where he was reunited with many of his beloved Asian ingredients. “I saw lemongrass, ginger, galangal. I started introducing these flavors.” Vongerichten had gotten three stars from the Times for his classical menu, but he noticed that his customers were asking for sauces on the side and, as often as not, leaving them unpoured. “I saw that in Europe people eat out on special occasions and eat at home every day. In New York, the opposite is true. After six months, I started to cook more everyday food. Lighter food. I put fruit juices in my sauces. I started an express lunch. At Italian restaurants, I saw oil everywhere. I’d worked in Provence, and I remembered the flavored oils. We started infusing different things in oils.” Within a year of arriving in New York, Jean-Georges was cooking food unlike anywhere else in Manhattan—or in the world.

In 1988, Times critic Bryan Miller bumped the restaurant up to four stars, and suddenly the shy, 31-year-old Alsatian with a heavy accent was being interviewed by CNN. The phone was ringing off the hook. “We went from $70,000 to $150,000 a week. All these chefs started coming in—Alice Waters, Alfred Portale, Jeremiah Tower, Daniel Boulud. I was working my ass off, putting in seventeen-hour days.”

It was a heady time. New York’s superstar chefs of the future were just gaining traction—David Bouley had left Montrachet and opened his own place, Boulud was at Le Cirque, Thomas Keller was at Rakel. “It was lot of pressure,” Vongerichten says. “I’m a guy who always questions myself. Every day was bringing the bar higher.” The pace was too much for his wife, who returned to France with their children in 1989. They subsequently divorced.

After failing to persuade the hotel to part with equity or back him in a new venture, Vongerichten teamed up with one of his most devoted customers, Phil Suarez, and found a space, an old pickup joint on 64th Street. They signed the lease on January 25, 1991, just as the first Gulf War was starting and the recession deepened. Vongerichten was sleeping on a foldout couch in Freedman’s studio apartment as he prepared to open his bistro in a kitchen with five burners and a single oven. The spartan ambience of the place, the paper tablecloths and pared-down menu, was dictated as much by financial constraints as by a vision of simplicity. It was not a propitious moment to open a restaurant in New York. His friend Keller had just been forced to close Rakel and retreat to California. But that restaurant was JoJo and it began his empire.

Now, fourteen years and a dozen restaurants later, Keller is the golden boy of the moment at Per Se, and Vongerichten is attempting, with a $2 million budget, to recapture that vision of simplicity at Perry St.

In the short run, Vongerichten’s biggest headache at Perry St. will be trying to accommodate the throngs of entitled New Yorkers who will want to be seen early and often at the 60-seat restaurant. If he follows his usual practice, he may hold open half the seats at the prime dining hours—eight to ten o’clock—until 48 hours beforehand. “Real New Yorkers don’t reserve a month ahead,” he says. If you have been to any one of Vongerichten’s restaurants in the past couple of years, chances are you’re in the database of 65,000 names, along with information about what you ate, where you sat, even whether you’re allergic to anything. Among other things, Vongerichten has perfected the art of catering to his regulars.

The rest of the empire, meanwhile, is in constant need of his attention. Spice Market is so mobbed, some of his faithful won’t venture there. (Personally, I find the food worth fighting for; those explosive little dishes are like Green Day songs—loud, hooky, and addictive.) V continues to be an aggravation. Vongerichten’s been feuding with his partners in the venture, and will decide after the summer whether to stick with it or turn over the key and walk away. He has revamped the menu, removing some of the “deconstructed” dishes that offended critics—like the French onion soup that consisted of a cup of broth with croutons and cheese on the side—acknowledging that New Yorkers don’t want too much novelty in their steakhouses. (Which raises the question: Do you need a chef of Vongerichten’s magnitude to cook a steak? Isn’t that like hiring Cy Twombly to paint your house?) I had dinner at V for the first time last month and was unexpectedly impressed. The room seemed full of out-of-towners, but the Niman Ranch rib eye was nicely charred and perfectly rare, while the appetizers, including an incredible baked oyster with wasabi and potato, were more exciting than anything I’ve had at other city steakhouses. I was less certain about the Jacques Garcia–designed, enchanted-forest-meets-fin-de-siècle-brothel room. “It’s a little feminine,” Vongerichten says. “I think our partners wanted something more like Peter Luger’s.”

If there was any doubt in my mind about Vongerichten’s continuing relevance and his ability to thrill, though, it was put to rest by a recent visit to Jean Georges. My girlfriend, Jeanine, was only mildly enthusiastic, if not openly skeptical. Let’s just say her idea of hell on earth is a fourteen-course, five-hour degustation; perhaps as a result she had, in my opinion, underdressed for the occasion, which led to a fight in the cab and a sense of impending dread as we were seated side by side at a banquette. A glass of champagne took some of the edge off. Them came Vongerichten’s signature egg caviar—scrambled egg, whipped cream, and vodka in a brown eggshell topped with Osetra. “God,” she said, as she cleaned out her eggshell, “I think I could eat a dozen of those.” She took my hand under the table as I ordered a bottle of ’02 Gagnard Chassagne-Montrachet.

The Next Jean-Georges

Adam Platt on rising kitchen talents.

The Every-Occasion Guide to Splurge Dining

If you’re going to blow a lot of cash, do it wisely by following the advice of our critics.