One day last month, John Tsolkas stood behind the counter at the Happy Burger, the Upper West Side coffee shop he owned with his older brother Gus, taking down phone orders. Pinning the receiver between his shoulder and his ear while collecting a check and punching the cash register, Tsolkas answered, “Happy!”

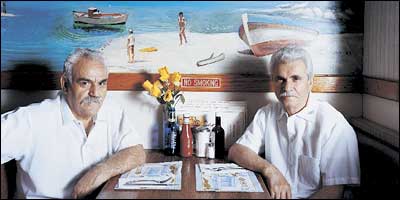

But Tsolkas, who is 65, was far from happy. He and Gus had owned the Happy Burger for more than twenty years, and had been in the business since they arrived in the United States 37 years ago. America and diners have generally been good to the Tsolkas brothers. When they immigrated from a small town in Greece where only a few kids their age went to high school, they gravitated to a business that had drawn their unskilled countrymen since the turn of the century. Starting with a doughnut shop on Broadway, the brothers owned several classic coffee shops on the Upper West Side: a dozen or so booths, pastries under plastic covers, the mother of all menus, and a platoon of eccentric regulars.

As New Yorkers have seen, dinermen work like mad, and the restaurant, on Broadway at 93rd Street, was the Tsolkases’ ticket to the middle class. But just at the point when most small-business owners want to start collecting a payoff for decades of labor, their situation looked tougher than ever. “When my lease ends in 2008—finish,” John Tsolkas promised that day. “I walk away.”

The end would come much sooner than that. One Saturday at the end of June, regulars arrived to find the Tsolkas brothers gone, their restaurant gated and locked. (“I’ve been eating at Happy Burger for twenty years, and one day they vanish without a word?” said Oscar Weizner, a regular who had taken refuge at a coffee shop down the block.) Happy Burger’s landlord, knowing he could get much higher rent from a new tenant, had offered the weary brothers an attractive buyout for the four years left on their lease. Tracked down at his home in Queens later that week, John Tsolkas had little to say beyond “Nothing last forever.”

Sad but true: The classic New York coffee shop is fading fast. The recession is part of the problem; according to Pan Gregorian Enterprises, a purchasing co-op for coffee shops and diners that has 475 local members, revenues were down 20 percent last year. But there are other forces at work, from skyrocketing rents to Starbucks hegemony, that are forcing coffee-shop owners like the Tsolkas brothers into retirement. Though traditional coffee shops do well in the outer boroughs, where the pressure to turn over leases isn’t as high, it is likely that over the next decade, those in Manhattan will go the way of Jewish delis and Irish bars—morphed beyond recognition or driven so close to extinction that the remaining few become nostalgia items or theme-park curiosities. (That’s already happening to Tom’s Restaurant, the neon-lit place at 112th and Broadway that became famous for the exterior shots on Seinfeld, and was briefly closed a few weeks back after a skirmish with the Department of Health.) “They are going to turn Manhattan into a museum,” Gus Tsolkas warns, as he gripes about the traffic enforcement that dissuades customers from double-parking to dash inside for a coffee, light and sweet, to go.

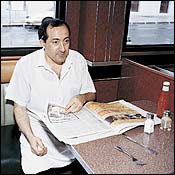

Consider the predicament of the Cosmic Coffee Shop, just south of Columbus Circle. “Everything high in sky,” moans Elias Tsinias, who says he’s seen his rent rise from $3,000 a month to $35,000 in the 32 years he has owned the place. Needless to say, his prices haven’t matched that elevenfold increase, and the rent is clobbering him. Furthermore, business continues to deteriorate despite the opening of the mammoth Time Warner Center a block away. “Big building,” he sneers, “but nobody come here. They want to spend $20 for eggs, instead of $6.” According to restaurant consultant Roger Fields, rent should not exceed 12 percent of sales. For the Cosmic, that means a gross of about $3.5 million a year. In fact, it brings in about $1 million a year—fine a few years ago but problematic now. Next year, the lease comes up for renewal; the owners say the landlord wants $75,000 a month, and “we won’t be here.”

Another problem is the trademark epic menu. Meant to appeal to a range of customers from the little old lady to the young couple who’ve just bought an expensive co-op in the neighborhood, it tries to give everyone everything. It worked for decades, but it isn’t working anymore. Certain high-volume, low-cost items do fine: A $5 burger, for example, costs about a buck for ingredients and requires less labor than most dishes—say, 25 cents’ worth. Add in the rent, electricity, and other miscellany, and that plate returns a 60 percent profit, which is why coffee-shop owners love to yell “Cheeseburger, cheeseburger.”

But keeping a vast inventory requires a feel for demand and an intimate knowledge of shelf life. An experienced coffee-shop owner who offers three kinds of steak knows that his porterhouses, vacuum-packed in Cryovac plastic, will last two or three weeks in the fridge. Some menus go so far as to offer lobster—which in turn calls for installing a tank, running to a friendly supplier around the corner, keeping a few packaged lobster tails around and hoping they don’t get freezer-burned, or storing a crate full of damp seaweed and live crustaceans in the fridge, hoping they’ll sell fast. (And offering a special on lobster Newburg the next day if they don’t.)

Even the basic cup of coffee is becoming a problem. At the low end of the business, street carts are flourishing—there’s one on the corner across Broadway from the Happy Burger—and Korean grocers sell coffee for 50 cents a cup. At the high end, Starbucks continues to spawn franchises, two of them within a block of the Happy Burger. How Starbucks can get people to pay $1.68 for a plain cup of coffee is a deep mystery to the Tsolkas brothers.

And there lies the final problem. To a business analyst, the obvious adjustments would be to simplify the menu and raise prices. But Manhattan’s continuing gentrification is alien to many of the dinermen. They don’t have the décor, menu, or food presentation to compete for newer, hipper customers, and they resist change lest they alienate their old-school customers. (Who are perhaps likely to die off a little faster than their upscale neighbors: “People used to eat every day bacon and eggs,” John Tsolkas complains. “Now they listen too much to their doctors.”) The Happy Burger, with its sunny waitress, Sylvia, was a lifeline to its elderly regulars. Ancient Sydney, with his bowl of cereal and 25-cent tips. Nannies, doormen, supers, cops. A British voice-over guy, Robert Mackenzie, reading scripts at the counter. Henry the ex-boxer, who had so many heart attacks in the Happy Burger that Sylvia was tempted to call an ambulance whenever he walked in the door. The hardest-core regulars kept their own condiments behind the counter: three kinds of maple syrup and a jar of honey clearly labeled property of the weizners. Try finding that at a Starbucks.

Some owners, loath to raise their prices, try to hang on simply by working harder and faster. Dimitri Kafchitsas, president and CEO of Pan Gregorian Enterprises, says, “They keep swallowing the raises until they just give up.” The Cosmic Coffee Shop guys have contemplated extending their day to 24 hours. Others, Kafchitsas says, have long leases and substantial reserves from decades of successful operation. They’re living on borrowed time, and it’s running out.

Still, some dinermen are finding ways to stick around. Fanis Tsiamtsiouris owns four Upper West Side coffee shops, all on Broadway between 77th and 100th streets. Though he operates on instinct like his compatriots at the Happy Burger—“You don’t go to school for this,” he says—Tsiamtsiouris seems to have found a business model that’s more in tune with the times. He’s streamlined the menus at his restaurants, losing the broiled bluefish, keeping the Jell-O and cottage cheese, and adding a few high-margin items that cater to relatively upscale tastes. “A few years ago,” he says, “I bought endive salad for $40 a box. My friend told me, You’ll lose the store! You don’t know how to buy.” But Tsiamtsiouris charged $9 for each endive salad and learned a valuable lesson.

He kept going, paying a decorator $40,000 to give the City Diner a slick quasi-Deco look. For the Key West, he chose tropical colors—very Miami Beach, or at least Miami Beach by way of the restaurant-supply houses on the Bowery. Sitting in his bustling Metro Diner, Tsiamtsiouris looks at his flashy décor and his new menu. “You take the American dream and mix it with the Greek dream,” he says, “and this is what you get. A mishmash.”

You also get the fallout of gentrification. When the City Diner—formerly the Argo—got its face-lift in 1996 and raised its prices, local scuttlebutt had it that some of the old crowd was encouraged to move on. “A guy who’s eating a filet mignon doesn’t want to sit next to a toothless grandmother nibbling on a toasted corn muffin,” a waiter at a nearby coffee shop snipes. (Then again, at least one of the Happy Burger’s regulars has made the Key West his new home.) Other clientele shifts came as well: “Intellectuals don’t like tropical,” Tsiamtsiouris reports.

In the forties and fifties, the basic coffee shop slapped on some chrome and became a diner. From the diners sprang hamburger places like the Jackson Hole chain, panini shops, and the glass-mosaic-tiled Moonstruck chain. Adaptable and forward-looking, these hybrids make more sense in the unforgiving Manhattan arena. Moreover, the owners are likelier than many to succeed. Kafchitsas notes that they have decades of coffee-shop experience in the family and “know where their penny goes,” innately balancing volume with profit margin.

Then again, not everyone’s so impressed. Ask Frank Tsiamtsiouris about his future, and he’s pessimistic. It’s customary for dinermen to sell these restaurants in installments rather than for one lump sum, and he worries that the likely buyer is someone who doesn’t really comprehend the business. “He will not do well,” Tsiamtsiouris predicts, “and I will lose my money.”