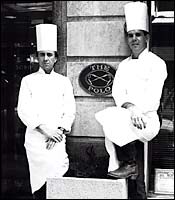

This is a tale of two chefs.

One left New York at a low point in his career and went on to create a restaurant unsurpassed in America. The other reached the pinnacle of the New York culinary world before going into a five-year restaurant exile. Both were scarred, and in some measure strengthened, by what can only be described as critical success and personal defeat. Both have been sorely missed by New York food lovers, who have fantasized for years about the chefs’ return to our city. Both will seek redress, if not redemption, at Time Warner’s new headquarters on Columbus Circle: one chef on the third floor and one on the fourth.

The chef who left town in defeat only to triumph in California is Thomas Keller, the lanky, whimsical, and compulsively hands-on creator of the mythic French Laundry in California’s Napa Valley. The restaurant, which could easily be mistaken for a nice but unremarkable suburban home, earned its reputation with its impeccable food and all-embracing service. Dana Cowin, editor-in-chief of Food & Wine, has followed Keller’s career through its ups and downs and says his great talent is that “he never tires of coming up with new, surprising, and well-executed variations of the possibilities of something as simple as an egg or a tomato. He explores every facet of an ingredient in every possible way—playfully yet intellectually and dramatically. I get the sense that he tries new flavors and dishes because he wants to please himself.”

The chef who walked away from full houses and universal acclaim at Lespinasse is Gray Kunz. Brought up in Singapore and Switzerland, educated in cuisine in Bern, and apprenticed under one of the greatest European chefs, Fredy Girardet, Kunz exudes courtliness and a sense of old-world decorum reinforced by Asian-inspired reserve and propriety. Similarly, his food is the product of two worlds, marrying classic French technique with a mastery of the flavors and ingredients that he first acquired during his childhood in the Pan-Asian food culture of Singapore, and then broadened during five years as a chef in Hong Kong. His cuisine is not so much fusion as the product of a man fluent in the food languages of Europe, India, China, and Southeast Asia. When Ruth Reichl gave her first four-star review in the New York Times, it was to him. “He struck me as the first European-trained chef who really understood Asian ingredients, not just as an accent, but innately,” recalls Reichl, now the editor-in-chief of Gourmet magazine. “You can’t learn this. I don’t know of any other chef who has it as part of his vocabulary. You add that to his impeccable training and it gives him something that nobody else has or can compete with.”

But in his final years at Lespinasse, then one of the finest restaurants in the world, Kunz was like a restless partner in an unhappy marriage. His dissatisfaction permeated the organization, and the staff could feel it.

The return of the prodigal chefs to New York was engineered by Kenneth A. Himmel, the intense, almost messianic developer of the vertical mall that comprises the first five floors of the Time Warner Center. Though this kind of self-contained city-within-a-city has been successful in places as disparate as Boston, Las Vegas, and Baltimore, it has rarely worked in New York. We may be a vertical city, but we are one that largely eats, shops, and consumes art on the ground floor.

One of Himmel’s stratagems was to put an arts attraction with some star power in the building. Jazz at Lincoln Center, under the direction of Wynton Marsalis, will draw crowds and lend chic. With that in place, Himmel set about creating what he calls “a restaurant collection” of five of the great chefs of America, whose combined luster, Himmel figured, would generate a gastronomic critical mass. “It wasn’t difficult,” he says, “to ask who would be the single individual who would turn everyone’s head and cause them to say, ‘My God, I should pay more attention to this project.’ ” The answer was Keller, whom he hotly pursued and ultimately enticed. At Time Warner, the chef will attempt to re-create the essence of the French Laundry in his new restaurant, Per Se, serving sublime cuisine on exquisite china in an Adam Tihany–designed room. The price tag for Per Se, reputed to be the most costly restaurant construction in history, is reportedly more than $12 million, much of it borne by Himmel’s organization.

Keller was even offered final approval on which chefs would be invited into the building, a power he exercised as firmly as the president of a Park Avenue co-op board. In addition to Keller and Kunz, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, whom Himmel had committed to early on, will join Chicago legend Charlie Trotter and sushi master Masa Takayama in the building.

Whether Himmel’s strategy works or whether it becomes a super-upscale outpost of American mall culture is the central question facing the developers of the $1.7 billion Time Warner Center. In the most recent comparable efforts, Las Vegas’s Bellagio, Mirage, and Mandalay Bay hotels have imported nationally famous chefs as the anchors of a Rat Pack–esque theme park for grown-ups. But New York already has the chefs and the urban cool built into the fabric of the city. In a way, we see ourselves as the theme, so why would we need the park?

It was both good luck and bad that took Thomas Keller from Soho to Yountville, California, an unremarkable little town in the Napa Valley that was just beginning to feel the effects of the American fine-dining revolution. The Napa Valley and its concentration of wineries presented Keller, who was flat broke at the time, with the opportunity to cook for a captive audience of aspiring epicureans who were ready to open their wallets to pamper their palates.

Unlike Gray Kunz, Keller was not a product of a cooking school. He got all his training on the job, starting by filling in behind the stove when the chef quit at the Palm Beach club his mom managed. Next he knocked around New England and New York City, picking up skills, staying under the radar, but learning as he moved from place to place.

He entered the world where cuisine and glamour meet in the early eighties as the chef at Raoul’s, a landmark among the first generation of hip eateries in renascent Soho. After Raoul’s, Keller joined the staff at the Westbury Hotel, working under Daniel Boulud, who recalls him as a very buttoned-up young cook, “boom, boom, get the job done, like clockwork.” From Boulud’s kitchen, Keller moved on to Taillevent in Paris, a Michelin three-star restaurant equally famous for its hospitality and its food. Those lessons were not lost on Keller at his next major adventure, a partnership with Raoul’s owner Serge Raoul: the spacious and pricey Rakel—“Ra” as in Raoul and “Kel” as in Keller—which was located on Varick Street. His sous chef there, Tom Colicchio, remembers splashing beet juice onto a plate so that it would spatter with a Jackson Pollock effect (it ruined many white aprons). Keller’s food was as high-flying as the stock market—until Wall Street tanked on October 19, 1987. By 1990, Rakel had downscaled to a mid-range bistro, causing Keller, who wanted no part of that, to leave Rakel and New York. His next real job (not counting a short stint as a consultant, which he has compared to streetwalking) was as executive chef at the trendy Checkers hotel in Los Angeles. There, he says, “I came to understand that the words executive and corporate never belong next to the word chef.” The arrangement was short-lived.

Kunz, during the same period, was on the express track. Near Lausanne, Switzerland, he cooked for five years in the illustrious kitchen of Fredy Girardet. From there he moved on to the Regent Hotel in Hong Kong, where he picked up passable Chinese while mastering yet another cuisine. “When I left there,” he says, “I felt as comfortable with the Chinese palate as with the French.”

It was in New York, though, that he became an international star. After earning good notices at the Peninsula hotel, where he went in 1988, Kunz was approached by the management of the St. Regis hotel. Eager to draw the Concorde crowd, they offered him carte blanche to cook whatever he wanted, whatever the cost, as long as it attracted the most passionate and free-spending clientele.

Almost from the moment he took the job in 1991, word got out that Lespinasse was the place. It was modern and exciting, despite the froufrou décor, with waiters in uniforms that could have been lifted from a luxury dayliner on Lake Geneva. But even with universal acclaim and a lot of money (he was said to be the highest-paid chef in the city), Kunz increasingly felt like a frustrated employee. He wanted to strike out on his own. “I don’t care if they paid me a million dollars,” he says, “it wouldn’t have been enough.”

He is characteristically mum beyond that statement, but it seems that what rankled was the idea that his reputation was somehow compromised by being a hotel chef—which gave him an unfair advantage over unsubsidized chefs who had to make both the food and the rent. Kunz, who trained in a strict hierarchical system where the chef was absolute monarch, was equally stymied by the fact that at Lespinasse, because of union rules, he couldn’t even fire a dishwasher who flipped a chinga tu madre at him, much less discipline an insubordinate headwaiter.

“What I did at Lespinasse,” says Kunz, “I want to do at Café Gray, just not truffled up.”

While Kunz’s star was fast rising at Lespinasse, Keller was out in Los Angeles, a chef without a kitchen, living catch-as-catch-can. Then, as he tells the story, “one day in early 1991, I was driving up Route 29 in Napa and I stopped in to see my friend Jonathan Waxman, who had a place called Table 29. He told me there was a restaurant for sale I might want to look at. I went there, saw the French Laundry, and somehow knew it was the place I was looking for all my life, and not knowing it until I saw it. I remember thinking, Yeah, this is home.”

He returned to L.A., where he compiled a microscopically detailed 300-page business plan while living on his credit cards. He charged $5,000 to hire Bob Sutcliffe, a lawyer with connections in the food business, who would help him raise the money to buy the place. Keller was looking for 48 small investors to pony up a total of $600,000, which Keller matched in bank loans.

The French Laundry made money its second year, 1995—“that is, if you think a profit of $672 in our second year qualifies as making money,” Keller says. Since October 29, 1997, the day Ruth Reichl wrote in the New York Times that the French Laundry was “the most exciting place to eat in the United States,” the reservation book has been 100 percent filled.

Meanwhile, in New York, Kunz was about to depart from Lespinasse. At first, the phone rang incessantly with proposed deals. I was spending a lot of time with him then, collaborating on a cookbook, and though we might be sitting on a park bench in Cobble Hill eating Krispy Kremes, he’d always answer the cell phone with the formality of a concierge at a five-star hotel: “Hello, this is Gray Kunz speaking, may I help you?”

But the deals never jelled. In 2000, he was a whisker away from signing a lease with the reclusive landlord William Gottlieb when Gottlieb dropped dead, leaving about a hundred buildings in limbo, Kunz’s space among them. He had several other deals in the works a year later, when 9/11 happened and threw a pall over everything. Dispirited, he wondered if he could ever work in New York again.

What distinguishes Keller and the restaurant that he and his general manager, Laura Cunningham (his girlfriend of nearly a decade), have built? Certainly, part of the answer lies in Keller’s perfectionist character. Michael Ruhlman, his collaborator on the best-selling French Laundry Cookbook, credits the chef’s “exploration of basic techniques and taking them to crazy levels.” Like having the cooks peel fava beans before they blanch them, an exceedingly laborious task, but one Keller believes is necessary to fix the green color of the beans. Equally left-brain is Keller’s kitchen dictum that “no liquid goes from one place to another without going through a chinois at least once.”

Obsessive attention to detail is one hallmark of Keller’s approach. It dovetails with his catechism of “respect for the ingredients.” For example, he decided some years back that fish should be stored with their dorsal fins facing up, as they do when they swim. “No one taught me that you should store fish this way,” he says. “One day it just dawned on me—if you have a round fish, you would never store it on its side. You’re stressing out the bottom fillet because you’ve got all that pressure on top of it. If you store it the way it swims, there’s no pressure on the meat itself.”

His kitchen is remarkably small, just 20 feet by 40 feet. There are very few obstructions hanging down, so that Keller, from his position close to the door to the dining room, can see all the plates. Equally important is that he is just a step away from the dishwasher, so that he can inspect what comes back unfinished. The quiet he insists on means he can always be heard and can hear everything.

Occasionally, as in all kitchens, especially those at this level, someone fucks up, and the chef will let his displeasure be known. First-time visitors often remark on these displays of temper. After a while you realize that this is the way all kitchens are, especially in the heat of battle. Keller expresses himself sotto voce but, if you are on the receiving end of his displeasure, fiercely. One night I watched as the new fish guy was having a little trouble keeping up. Keller walked over to him and said something. The kid tried to explain himself when Keller interrupted: “I talk, you listen. That’s the way it works. Got it?”

Where other chefs may try to maximize the complexity of each dish, Keller views the meal as a kind of gustatory epic with more acts than the Mahabharata. In his detailed service manual he writes, “All menus at the French Laundry revolve around the law of diminishing returns, such as the more you have of something the less you enjoy it. Most chefs try to satisfy a customer’s hunger in a shorter time with one or two main dishes. The initial bite is great. The second bite is fabulous. But on the third bite, the flavors lessen and begin to die.”

“Many chefs” he continues, “try to counter this deadening effect by putting many different flavors on the plate in an attempt to keep interest alive. In doing this, the focal point is often lost and the flavors get muddled … In five or ten small courses we try to satisfy your appetite and spark your curiosity with each dish. We want our guests to say, ‘God, I wish I had one more bite of that.’ ”

In the dining room at the French Laundry, nothing breaks the serene calm and pursuit of pleasure. With its pale walls devoid of art and the muted lighting, the effect, oddly enough, is of a sensory-deprivation tank—the room fades away; the other diners become invisible and inaudible. The experience of a meal is as artfully orchestrated as a symphony. All one notices is the bright tablecloth, the waves of aromas, the succession of textures, the attack and recession of flavor. As I recollect a meal of truffles and custard, poached lobster, and pig’s ear and yuzu pudding, I recognize a giddy sense of longing that I felt as a teenager: infatuation.

As Keller seeks to direct a meal of many intensely focused small acts, Gray Kunz creates by adding layers, ingredients, and accents to any recipe almost ad infinitum—yet he produces a dish that makes a single statement. What is striking is how many ingredients he can draw on from his taste lexicon. Star anise, black onion seeds, lavender flowers, sumac, Indonesian kecap manis, and honeydew juice are no more or less exotic to Kunz than salt and pepper. He tastes, retastes, seasons, reseasons, calls for this ingredient or that, and slices so fast that his blade is like the blur of a hummingbird’s wing. You won’t get his attention when you talk to him, but if your execution is wrong, he might show you how to do it in a manner as gentle as that of a Montessori-school teacher. Or, if you’re some diffident line cook who should have known better, you’ll see his ire before he speaks a word, because Kunz’s face reddens with emotion, quickly followed by colorful imprecations in any of the five languages he speaks.

A few years ago, when we were working on our cookbook, we organized it around flavors (which is how chefs create recipes). One day I suggested to Kunz that we make something based on bitterness, or at least that we use that taste as a starting point. It was a crummy late-November day as we trudged in the rain to a depressing city supermarket. With an ordinary, shrink-wrapped supermarket chicken as the base of our meal, Kunz conjured.

“Bitter, okay, let’s start with almonds,” he said and flipped a pack of shelled almonds into the shopping cart.

“Now to balance it, something fruity,” he mused as his gaze lit on dried cranberries. “These will be exactly right because cranberries have a bitter edge but some sweetness.”

Shallots came next, because Kunz likes shallots whenever he can work them into a recipe. They broaden flavor with their aroma and underscore any sweetness in a dish. Leeks work to similar effect but are a little more focused, so he picked some of them, too. He was getting up a head of steam at this point. “Okay, some vinegar for acidity,” which brightens taste. “I think we’ll use cider vinegar because apples are a fall item and so are cranberries.”

He paused to consider his next move. “Apple-cider vinegar, cranberries. It feels New Englandy. Let’s go for sweetness with maple syrup to balance things out. And nutmeg—that will give it a bouquet that keeps the flavors from getting too diffuse. Anyway, when I think of New England in the fall I like apple cider with a grating of nutmeg.” Finally, butter, because such a hearty, rustic dish cries out for nuttiness.

This recipe, composed by Kunz on the spot—oven-crisped chicken with maple-shallot-vinegar glaze—turned out to be the most popular recipe in the book. In the same manner that a musician can “hear” a complex melody in his head and know it is good music before he ever picks up an instrument, Kunz is always hearing taste melodies.

When Kunz finally made the break from Lespinasse, he learned, to his surprise, that simply being an acclaimed chef is not enough to attract the backing needed to succeed in New York. The restaurant consultant Adam Block (who is advising all the Time Warner chefs except Vongerichten) tried to help Kunz set up a new venture. But as the deals fell through, the two parted ways. Block’s affectionate but clear-eyed assessment was that great chefs do not necessarily make great businessmen; their ambitions rarely match up with the restaurant Realpolitik of profit margins. Kunz finally came to understand that “I had to go through a learning curve, a very steep one for how to comport myself in the business world.”

Two years later, after Kunz agreed to give Block oversight of his business strategy, the consultant helped bring the chef into an arrangement with Vongerichten for the restaurant Spice Market, which is scheduled to open in mid-January. There, Kunz and Vongerichten have devised a modern menu based on Southeast Asian street food. Next, Block got Kunz into the Time Warner deal. Kunz’s restaurant there, Café Gray, will be fine dining, but on the casual side—a place along the lines of Atelier in Paris, the creation of another demigod escapee from formal haute cuisine, Joel Robuchon.

Kunz invited me to a first tasting of proposed recipes. Among the things dished out were our chicken with maple-shallot-vinegar glaze, risotto and mushroom ragout, and an experiment: a moderately tweaked sole Colbert, a fried fish with herbed butter that is a French classic. Looking over this menu, Kunz’s wife, Nicole, commented, “Where’s Gray Kunz?” She had put her finger on something. The food was good, but something was missing—his other food languages.

“I need to Kunzify it more,” he said.

This is precisely what he did in the next week’s tasting. Not Eastern, not Western, just Planet Gray. He started with a creamy, herb-rich, and piquant mulligatawny soup accented with preserved lemons, bracingly hot curry, kaffir-lime leaf, and lemongrass, served in a demitasse cup with a lattice of crisped taro on top. Most impressively, the second run at sole Colbert was a more confident example of Kunz’s ability to transform classic recipes by giving his Asian instincts free rein: a panko (Japanese breadcrumbs) crust seasoned with cardamom and coriander seed, the center of the fish filled with coins of spiced, braised lettuce stems. A brasserie dish, for sure, but a global brasserie recipe.

“What I tried to do at Lespinasse I want to do at Café Gray in a more casual and affordable way,” he explains. “Not dumbed down, just not truffled up.”

Kunz and Keller are now in countdown mode; Per Se is set to open on February 16 and Café Gray sometime in early March. Keller is closing the French Laundry for a four-month renovation while he and Cunningham devote their time to fine-tuning the New York operation. Keller is aching to begin, thinking constantly about the minutiae of Per Se. On a drive back from Yountville, he talked at length and more deeply than I would have thought possible about plates, telling the story of his risotto bowl, which has about four inches of lip on each side and is three and a half inches deep.

“I wanted something that would keep the risotto warm and all at the same depth,” Keller said. “While walking through the museum at Reynaud in France, I came upon a piece called a trembleuse. It was made for Marie Antoinette, so that she could have soup in her coach without spilling it. The solution was a wide plane with a very deep center. And I said, ‘That’s what I want for our risotto.’ ”

Chefs, when they are not thinking about making food, are thinking about how to serve it. Kunz and Keller think about such things all the time. Yet I never heard either obsess over their roll of the dice at Time Warner Center.

With a tone that is either fatalistic or just plain confident, Keller said simply, “If the building makes it, we all make it.” He turned to look out the window at the fog bank rolling in off San Francisco Bay.