Medical Miracle #4

Problem: Eleven-year-old boy. Born missing one ear and mostly deaf in the other. Needs treatment for disability and cosmetic issues. For years, nothing has been done. Doctors have no solutions; mother can’t afford expensive surgeries.

Doctor: Thomas Romo

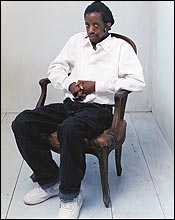

Patient: Terrell Davis

Brenda Davis went into labor six weeks early on the night of June 25, 1993, and after a complicated delivery, her son Terrell was born without a heartbeat. “They took him away to be resuscitated before I could see him,” she says. Davis was relieved when she finally saw the boy in the neonatal ward, but a new problem presented itself: “I saw that he only had one ear.”

Terrell was born with unilateral microtia—a birth defect that impedes ear formation. For the first eleven years of his life, he had one normally formed ear, the left, in which he was totally deaf, and some bumpy skin where his right ear should have been, though he could hear slightly in that ear. Terrell communicated through sign language at the ASL and English Secondary School near Gramercy Park and read lips and body language to communicate with his family at home in Harlem. He was exceedingly shy. He wouldn’t join in activities at school “and he wouldn’t attempt to speak with anyone until he was very comfortable,” says Brenda. “People would gasp and point on the bus, trying to get a look at his ear,” Brenda says. “It made him very uncomfortable.”

Brenda, a single mom and clerical assistant, often had difficulty paying for Terrell’s care and getting him to weekly speech-therapy sessions at Manhattan Eye, Ear & Throat Hospital. “It was very strenuous, of course,” she says of raising Terrell, “but as a single parent with a disabled child and another child, I don’t know any other way than hard.” In addition to microtia, which has no known cause, Terrell also has asthma, which prevented him from undergoing a popular, strictly cosmetic surgery for microtia that involves taking rib cartilage to reconstruct the missing ear. “Even if he could have had it,” Brenda says of the surgery, “we couldn’t have afforded it, and it wouldn’t have restored his hearing anyway.”

Last year, Terrell was referred to Lenox Hill Hospital, where he was placed in the care of Dr. Thomas Romo, the hospital’s chief of facial plastic surgery and the president and founder of the nonprofit Little Baby Face Foundation, which helps children with facial deformities. “I saw Terrell for the first time, and I thought, Wow, no one’s taken the time to help this kid,” says Romo. “He’s almost deaf, and needn’t be.”

Microtia patients suffer from conductive hearing loss—a condition caused by the lack of an ear canal, as opposed to nerve problems. In most cases, the condition can be corrected with a device called a bone-anchored hearing aid (BAHA). A processor placed behind the ear picks up sound, then transfers it to an implant, surgically placed in the skull, which sends electric signals directly to the nerves responsible for hearing, effectively bypassing the ear canal. On Terrell’s first visit to Romo’s office, the doctor fitted him with a test model of a BAHA. The device wasn’t surgically implanted—it was jerry-rigged to function externally—but it provided the same improvements an implanted BAHA would bring. “I went up to Terrell after I put it on, and said quietly, ‘Hey, Terrell. How are you doing?’ ” says Romo. “His face lit up. For the first time in his life, he could hear a whisper.” Brenda, Romo’s nurse, and Romo all began crying. “It was infectious,” says Romo. “You could see how amazed he was.”

Romo let Terrell keep the modified hearing aid until LBFF was able to get him an implanted one. “When he went outside after that visit, it was unbelievable,” says Brenda. “He jumped when a man next to us sneezed—he’d never heard that before.”

In January, Romo operated on Terrell’s right ear, reforming it by using an innovative type of plastic that can be shaped with great detail and is compatible with living tissue, creating a result that’s remarkably true to life. Save for a few indentations here and there, “it looks completely normal,” Brenda says. “It’s absolutely amazing.”

Terrell now has two fully formed ears, and when his permanent BAHA is installed in the next few months, he’ll look and function like a normal child. Already, “we see a significant change in Terrell’s self-esteem,” says Brenda. “He can do normal things now, like wear sunglasses; things that we all take for granted.” His communication skills are improving, too. “I have to keep reminding his older brother, ‘No talking behind Terrell’s back—he can hear you.’ ”