The crystals in Dr. Howard Bezoza’s center on 57th Street are encased in glass boxes, embedded in the walls, and labeled with their palliative effects and relevant chakras. A chunk of teal-and-black malachite (fourth chakra) is good for the tendons, muscles, and throat; purple fluorite (sixth chakra) promotes clear thinking. There are a few Huichol Indian masks and god’s eyes adorning the walls. “These things say in a nonverbal way that this office accepts the fact that there is a mystical aspect to human life,” Bezoza explains. “Although as a doctor, I’d prefer life to be two-dimensional.”

Down one hall, a woman snoozes in a recliner, covered with a plaid blanket, her arm attached to an IV delivering a yellowish liquid into her vein. She is indulging in a vitamin infusion, a specialty of the house.

Dr. Bezoza is a living advertisement for his vitality regimen. At 47, he exudes the hyperactive energy of an adolescent, rapidly and defensively spouting statistics gleaned from Harvard surveys and a Journal of the American Medical Association article about alternative medicine. “There’s as much money being spent out of pocket on alternative remedies as there is being spent by third-party insurers,” he says, citing a Harvard study. “Who seeks alternative remedies? The smartest, most successful people. So we can’t continue to proselytize this issue of the quack!” Bezoza has attracted a large, well-heeled (insurance doesn’t cover intravenous vitamins) following that includes actresses, socialites and Wall Street tycoons. The actress Olympia Dukakis and the model Tahnee Welch are among his patients. Bezoza’s back-combedorange hair and beard and protuberant eyes give him a slightly werewolfish look, but you get used to it. He is trim inside his black turtleneck, thanks to daily oral dosages of a plant-based testosterone (the equivalent of eating ten yams, he says) he started taking last year to vanquish middle-aged fat. He also follows a “Paleolithic diet” (one third animal, two thirds vegetable, based on the foods supposedly available to early man).

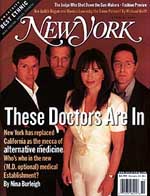

“New York is the mecca of high-level alternative medicine,” he says. “You’d think it is California, but the largest concentration of competent alternative practitioners is right here.”

There was a time, back in the seventies, maybe, when Howard Bezoza and his ilk were stereotypically associated with Marin County or Santa Monica. If California was ever alternative medicine’s mecca – and many alternative healers in New York dispute even that – it is no longer the case. New Yorkers, especially rich, famous, fabulous New Yorkers, are now flocking to shamans, spiritualists, Chinese masters, and alternative M.D.’s as fast as their Town Cars can carry them.

The national trend toward alternative medicine in the past five years has been led by the wealthiest, most educated people, and one of the largest concentrations of that demographic is not in the California hills but right here. To get an appointment with many of New York’s top practitioners, you need a referral from a VIP – or be prepared to wait several months. Health insurance won’t cover many of these treatments, so a walletful of cash is imperative.

New Yorkers can choose from a vast array of alternative medical services, from storefront acupuncture in Chinatown to spiritual healers, bodyworkers, and purveyors of herbal medicine and vitamin supplements in tony apartments and clinics. Some of the practitioners are M.D.’s with prestigious academic appointments and faculty positions. Others have taken courses with gurus, spiritual healers, or Chinese medicine masters. Still others simply believe they have “a gift.”

Though some of their techniques are buttressed by clinical studies conducted by Harvard professors and are on the verge of being accepted into the canon of Western medicine, others simply must be taken – or not taken – on faith. But for many in New York’s new medical Establishment, Western medicine is beside the point. They believe they are in the vanguard of the healing arts; science will eventually catch up.

Bezoza is one of the many New York practitioners whose medical epiphany occurred on the West Coast. Trained as a conventional M.D. in the seventies, Bezoza was 28 years old and working in the emergency room of Coney Island Hospital in 1980 when he had a bad case of burnout. He decided to take some time off and drive cross-country in his RX-7. In L.A., he went to a lecture given by vitamin C missionary Linus Pauling at UCLA.

“I had one of those life-changing experiences,” he says. “The first guy who spoke was a Biospherean, and he talked about studies that showed undernutrition – not malnutrition – led to a 30 to 50 percent increase in the life span of rats. Then Linus Pauling spoke – next to Einstein, the greatest scientific mind of the twentieth century. He was in his eighties and taking six 1,000-milligram vitamin C tablets a day. And I knew he was right.”

When Bezoza returned to New York, he left the emergency-room job and went on a worldwide pilgrimage to learn about alternative therapies, visiting skin-treatment centers at the Dead Sea and cancer clinics in Baja. In 1981, he hung out a shingle aimed at the beautiful people in New York who were watching their attractiveness wither under the disco onslaught of cocaine, nicotine, booze, and Quaaludes. “I really had the idea that beauty was related to health. We had a diagnosis called model malnutrition – for women who were trying to live on two Graham crackers a day. I could bring them the equivalent of two steaks and three mangoes with my infusion therapy.”

Beauty is no longer the focus of his practice. He now spends most of his time interviewing patients (a session usually runs $250 to $300) and dispensing supplements and infusions. He still practices conventional medicine – if someone needs antibiotics, he will prescribe them, for example, and he regularly sends his patients out for high-tech MRIs, CT scans, and sonograms. Often, his patients have already seen conventional practitioners and are still uncured of their asthma, allergies, inflammatory bowel syndrome, or cancer. “I’m Dr. End-of-the-Line,” he says. “People who come to me get more than the HMO minute. I am acutely aware that people are spending their own money to see me.”

Olympia Dukakis discovered Bezoza seven years ago, when she was seeking alternative ways to deal with osteoporosis. “There wasn’t that much information out there, so I started to read everything, hoping to find people to help me,” she says. “I knew there was a nutritional component, and as I read, I kept coming up against his name. I found out he was right here in New York. He did a lot of things, which I don’t want to talk about, and he really turned me around.”

Dr. Ron Hoffman has been operating his Hoffman Center on East 30th Street for about as long as Bezoza has had his center. But Hoffman, with his spectacles and subdued self-consciousness, has a different bedside manner. Hoffman’s center has offered conventional medicine, acupuncture, vitamin drips, herbal medicine, and other nontraditional cures since 1981. He has been prolific in writing about his work. Tired All the Time: How to Regain Your Lost Energy; Intelligent Medicine: A Guide to Optimizing Health and Preventing Illness for the Baby-Boomer Generation; and 7 Weeks to a Settled Stomach are three of his self-help books.

“I intended to do this from the get-go,” Hoffman says of his decision to practice what is often known as “complementary medicine,” meaning that it works with, not in replacement of, more conventional treatments. “I call it intelligent medicine.” Hoffman studied anthropology in college, and his approach to the various healing systems of the world “is not hierarchical.”

Most of Hoffman’s patients suffer from chronic fatigue syndrome, digestive problems, or allergies. He also is pioneering a non-conventional treatment of autistic children involving a digestive hormone.

Where Bezoza is a booster, Hoffman is restrained about the benefits of alternative therapies. “People present real dilemmas,” he says. “They have an unsavory option ahead, and this has an aura of the magical. And sometimes there is a magical, unexpected outcome. Other times, the verdict is, you’ve still got to have that operation.”

A native Californian, Hoffman says nontraditional healing in New York dates to the forties and the physician Carlton Fredericks, who had a popular radio show on nutrition. “There is a big difference in the style of the New York practitioners” compared with the West Coast doctors, he says. “Some are doing the touchy-feely spiritual stuff, but there is a more hard-assed approach here. In California, it’s more of an aesthetic thing.”

The granddaddy of complementary medicine in New York is Dr. Robert Atkins, author of the best-selling Atkins diet books and founder of the Atkins Center for Complementary Medicine, a seven-story facility on 55th Street. Atkins has been in practice for 40 years and claims to have treated more than 60,000 patients, among them seventies diva Stevie Nicks (who credits Atkins’s diet with helping her to shed 30 pounds for her recent comeback tour).

Atkins, 68, is a cardiologist by training, and his reducing diets are high-protein, low-carbohydrate regimens – which have become popularized in best-selling books. Atkins’s practice attracts the chronically ill, especially diabetics and people with allergies, cancer, and multiple sclerosis. His clinic offers nutrition, herbs, acupuncture, prolo therapy, and supplements in conjunction with Western drugs when necessary to treat chronic ailments, including allergies, autoimmune diseases, diabetes, cancer, pain, and gastrointestinal complaints – as well as weight problems.

“For the first fourteen years of my career, when I saw a heart patient I would say, ‘How have you done since your last visit?’ And if they said ‘No change,’ I’d say ‘Good,’ ” Atkins says. “Now if they say ‘No change,’ I say ‘What have you been doing wrong?’ The expectation of mainstream doctors is that heart patients don’t get better. Here, the expectation is yes, they can. We are changing the world.”

Like many of his colleagues, Atkins began exploring diet, vitamins, and nutritional medicine when he became frustrated with the results of traditional pharmaceutical medicine. Over the years, he has seen the popularity of alternative health care grow, especially in New York: “New York doctors are at the head of this, because more and more people here are looking for alternative doctors. On the West Coast, the problem is a high density. West Coast doctors are more vegetarian, and most of us here are more carnivorous – that’s a difference.” Atkins also points out that on the West Coast the law is much stricter.

At first, complementary, innovative, or alternative practice drew the full scorn of the New York medical Establishment, and state law reflected that. Occasionally, practitioners had their licenses yanked by the medical boards, which judged a doctor’s work by whether it coincided with the community standards of practice used by the rest of the profession. In 1994, New York’s alternative-medical-practice act restated the standard of practice to whatever works – within the parameters of safety, effectiveness, and informed consent. That change in the law made life much easier for New York doctors who want to prescribe herbs, yoga, acupuncture, or supplements instead of or along with pharmaceuticals.

“New York is a lot less paranoid than it used to be,” observes Dr. Woodson Merrell, one of the city’s leading alternative-medicine practitioners. Merrell, 50, a hale, outdoorsy fellow who tends to wear corduroys and flannel when he sees patients (many from the music industry), is another West Coast native actually weaned on homeopathy and organic food. He was born in San Francisco, the grandson of a Sierra Club member; his parents treated his infant croup with homeopathic medicine. In college in the sixties, Merrell took up yoga and studied political science. He went on to medical school intending to combine Eastern and Western healing techniques.

Now he “recommends” (not, he points out, “prescribes,” because it is technically not allowed) herbs and supplements, yoga and meditation and acupuncture, nutritional advice and homeopathy, from his small office on 67th Street, where the walls are lined with books on Chinese and Tibetan medicine and herbs. He will prescribe pharmaceuticals when they’re called for, but only at an absolute minimum. Many of his patients are referred by their doctors. “An allergist will have a patient on cortisone for the eighth time, and finally he will say, ‘Go to Dr. Merrell; maybe he can do something.’ “

Merrell teaches herbal medicine at Columbia and is the director of Beth Israel’s Center for Health and Healing, which aims to combine alternative and conventional medicine. He also serves on the state’s complementary-medicine board and debates the so-called quack-busters on panels. He credits the National Institutes of Health for funding an office of alternative medicine ten years ago. Merrell also says the aids crisis, which drove desperate patients toward unconventional medicine, gave conventional doctors a new respect for alternative cures.

“There was almost nothing infectious-disease specialists could do to help them in the beginning,” he says. “Their patients were coming to them doing these wild things, and the specialists saw that some of them were working, against all the odds. They became less antagonistic after that.”

Merrell and his colleagues face another obstacle in their quest for legitimacy: The FDA doesn’t regulate the supplements industry. Five years ago, Congress passed legislation sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch – who represents Utah, home to the largest number of supplement producers in the country – that essentially forbade the FDA from treating supplements as drugs and applying to them the same stringent testing measures. The result is that many companies – hoping to cash in on a $12 billion market – are now labeling their products as supplements willy-nilly, with no standards.

“This is a huge business ripe for fraud,” says Merrell. He and the other doctors interviewed for this story who treat patients with supplements say they study the companies and select those they know to be supplying clean and genuine products. Merrell says he recommends supplements from companies that show they have independent lab testing.

Dr. Raymond Chang, a Hong Kong-born cancer specialist, personally visits herb farms in China; he compares his knowledge of medicinal herbs to that of an oenophile’s knowledge of wine. A rumpled 41-year-old who got his Western medical training at Brown University after years of apprenticeship to Chinese masters of herbal and acupuncture treatment, Chang operates his Meridian Medical Group on 30th Street off Park Avenue South almost exclusively for the seriously ill, or what he calls “difficult cases,” cancers and infertility. An oncologist by training, he is an attending physician at Cornell. His clinic offers his services and also those of an acupuncturist and a Tibetan-medicine practitioner. His patients come from around the world – some of them, he confides, so important the entire clinic is shut down to the public when they fly in for a consultation.

“There are some things Chinese medicine can help – fertility, for example – but kidney stones will not be helped by acupuncture,” Chang says. “Some alternative M.D.’s will tell patients not to get chemotherapy. Our determination is based on whatever is best for the patient.”

Chang says he “reluctantly” got into Western medicine because his family wanted him to. At first, he was dazzled by Western science: “In the classroom, you do not realize the limits. In terms of pharmacology, physiology, biochemistry, it all works out. But in a clinical setting, when you see patients, you find lots of cases where Western medicine cannot identify what is wrong.”

Just five years ago, he was actually reprimanded for discussing herbal treatments at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, where he was then an associate clinical staff member. Now most medical schools offer courses in complementary medicine; Chang teaches one at Cornell. Yet Chang isn’t entirely happy about the new acceptance. He worries that the enthusiasm is just a fad auguring rampant commercialism and, ultimately, a bad name for the kind of medicine he practices. “I am keeping a low profile,” he says. “This overhype will come back to hurt alternative medicine. The questionable quality of the products will invite skepticism from doctors. It will turn out it doesn’t work for certain conditions, and patients will be disappointed.”

Frank Lipman, an M.D. from South Africa, is the acupuncturist of choice for aids patients. He, too, reputedly has a client list of famous people – whom he indignantly declines to name. His interest in nontraditional medicine began in Africa, where he was intrigued by herbal medicine and homeopathy. In the U.S., he started studying acupuncture during his residency in the South Bronx, and eventually he did a psychiatry rotation at an acupuncture clinic there. In 1987, he got his New York acupuncture license. He now runs his own clinic on Fifth Avenue. Patients are charged $325 for an initial consultation and $125 for subsequent visits. Insurance usually covers these sessions.

Lipman says he turned to acupuncture because he was disillusioned with the impersonality and cursory nature of American medicine. “In South Africa, you take a good history, because you couldn’t afford to do all these tests. You learn to listen to patients.” He now practices what he calls integrated medicine, addressing lifestyle, nutrition, and general health along with providing acupuncture treatments.

Like Chang, Lipman readily acknowledges the limitations of his practice. He says acupuncture is most effective against headaches, back pain, menstrual problems, infertility, digestive problems, and stress-related disorders. “If I need to prescribe an antibiotic,” he says, “I will, but for the most part I don’t. I’m not against Western medicine. We are not saying it’s either-or. We are not claiming to cure cancer or aids, but I do think it can help cancer or aids patients.”

Lipman’s client list has evolved over the past five years as the public has grown more accepting of Eastern medicine. “When I first started, my clientele were really from the artsy community and HIV community. Over time, I’m getting more and more mainstream people, more Wall Streeters. It’s now beyond trendy. It’s still trendy, but it’s more established.”

Success, of course, breeds criticism. The most vocal opponent of alternative medicine is Wallace Sampson, former chief of oncology at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center and a Stanford professor of clinical medicine. He chaired the National Council for Reliable Health Information, a group that sees almost no medical advantage to any of the alternative offerings. Moreover, the group blames the cultural relativism of the sixties for infecting medicine with pseudoscience. “I see no benefit to any of it,” Sampson says. “There might be benefits to meditation and relaxation – if nothing else, to acquire a better quality of life – but it has very little to do with life extension and susceptibility to disease.”

Sampson has a well-polished, William Bennett-like screed as to how the alternative-medicine virus entered the culture. “Harvard offered courses, and then the hospitals in New York started doing it. These programs are set up by rich people with an ideological agenda that nature is good and science and technology is bad, that truth is a relative, culturally determined thing, so that science is diminished. There will be a price to pay for this later on, in terms of health and the indoctrination of medical students.”

Doctors practicing complementary medicine, however, strongly believe that the next century will prove to the quack-busters that nontraditional treatments have a place in modern medicine. They believe that the older healing arts will be merged with Western medicine to create holistic health care that is both high-tech and ancient. In their vision of the future, patients will get MRIs, qi gong, and herbal remedies at the same clinic.

There is a rough dividing line in the alternative-medicine community between those who’ve been educated at medical school, or at least done some serious post-graduate work in science, and nondegreed “healers” and mystics, the sort one associates with Marin County or Santa Fe. But complementary M.D.’s do not deny that they exist on the same spectrum, since, almost by definition, they’re open to the possibility that a psychic healer, for example, could do a body some good.

And in Manhattan these days, there’s an army of unconventional, nonscientific healers, led by an elite set whose cell-phone caller I.D.’s are alight with the home numbers of celebrities and the very rich, who rely on them for everything from ritual healing to ghostbusting.

Fashion model turned actress Carolyn Murphy is just finishing a session with emotional healer Aleta St. James when I arrive at her Hell’s Kitchen healing sanctuary. Two panting white Maltese dogs greet me at the door, where I’m instructed to remove my shoes before entering a delicately painted boudoir of an apartment. Huichol Indian masks peer down at the peach-colored rug from the peach-colored walls.

Aleta St. James is Guardian Angels founder Curtis Sliwa’s older sister. Somewhere during her life journey from merchant seaman’s daughter with a psychic gift to actress to globe-trotting healer-to-the-rich-and-famous, she changed her name. In her early fifties now, she slightly resembles Victoria Principal, and pads around barefoot, toenails painted Vamp.

“There used to be sacred secret schools for this,” she says. “Now people are evolving very quickly and moving into the millennium. People’s stuff backs up on them, and they have to learn to deal with their emotions and not be debilitated by them. There is such a parallel between sickness and emotions.”

St. James used to treat a lot of aids patients, but now her clients tend to be physically healthy members of the entertainment or fashion communities. New patients wait a month or more for a first visit. An hour costs $200 for the first visit and $150 thereafter. She also leads trips to Mexico on which clients can swim with dolphins and meditate at Mayan ruins in search of a higher plane (although she returned from her latest dolphin trip with a decidedly earthly intestinal parasite).

Her method is a combination of repressed-memory recovery, quasi-Freudian psychotherapy, touch therapy, scanning for energy blocks, and breathing exercises. In a brief exhibition session, we proceed into the healing room after she asks me a few questions about my childhood relationships with my parents. It’s dark and there’s a futon on the floor, a Buddha and some crystals in the walls. I lie on my stomach. With her hand on the small of my back, she asks me to mind-travel back to when I was 6 and let “Little Nina” come out. “Tell her to let go of her fear,” she says. “Exhale the fear. Do you feel it leaving? Do you see the light?”

After a few minutes of deep breathing with St. James’s hands on my back, she places a small object in my hand, puts headphones on my ears, and leaves the room. My brain is filled with the sound of Gloria Estefan singing “Coming Out of the Dark.” I peer down and in my hand is a glass cylinder with a silver spring inside it. Silver, St. James explains later, is the color of the maternal. A white Maltese hops on my chest and licks my nose just as the song ends. It’s the signal that the session is over.

“She helped me become a better person,” says Carolyn Murphy, 25, who sought out St. James’s services after reading about her in Allure two years ago. Although Murphy says St. James has mostly helped her work through the tensions of everyday life by getting her centered, the healer has also alleviated some physical problems. “I’ve had stomach ailments where I’ve gone in and she’s placed her hands on my stomach and it’s gone away. I’ve had sinus headaches she’s cured. She’s a really powerful woman. There are people put on earth to heal people, but you have to be open to it. She definitely has a gift.”

The doorknobs to nutritionist Oz Garcia’s inner office are green crystal balls. The outer office is decorated with magazine articles about him published in W, Hamptons, and Allure. Garcia advises the likes of Winona Ryder and Judith Regan, along with a flock of supermodels, about what to eat, using hair analysis and a method of eating tailored to individual metabolic types. Last year he published a book called The Balance: Your Personal Prescription for Supermetabolism, Renewed Vitality, Maximum Health, and Instant Rejuvenation.

Garcia, born in Cuba, was a fashion-and-beauty photographer in the seventies when he became a natural-health convert. In his mid-twenties, he suffered debilitating migraines, and no prescription drugs seemed to help. On an assignment to photograph a visiting guru, he heard the lecture that changed his life and decided to try meditation and natural supplements. Soon he was a strict vegetarian, growing sprouts in trays in his loft apartment, and hadn’t had a headache in months. He apprenticed himself to naturopaths and other holistic healers, studied at the Hippocrates Institute in Boston, then went into business as a nutritionist in the eighties. Garcia says his job is to “educate” – not treat – people. “We work in conjunction with their doctors,” he says.

Most of Garcia’s clients are not exactly sick, but they come to him complaining of tiredness, weight gain, or feeling emotionally or temperamentally off. In a first session, he will quiz people about how they live and what they eat. He instructs them to keep food and activity logs, and to individualize their diets, he sends people for blood work and hair analysis. “Food when used properly can be therapeutic,” he says. “We are educating clients about the curative role of food.”

Garcia advises a diet with “protein-accurate” and “carbohydrate-accurate” goals. Like Bezoza, he believes Paleolithic man ate a balanced diet of protein, carbohydrates, and fat, but modernity has served up a groaning board of carbohydrate-laden food that turns people into sluggish, fleshy addicts. “The biggest culprits are pizza, pasta, cookies, cakes, bagels. It’s this doughy diet people eat that causes neurochemical changes, and they become addicted.”

Lithe and elegantly dressed in cashmere and velvet, Garcia doesn’t appear to have been near a bagel for years. He says he eats bread “on a social basis” only. The last time he ate fast food was after a vision quest in Zion National Park, Utah –

driven to it only by desperate necessity. “We’d been fasting, and we were on this unbelievable high and were starving. The only place we could get food on the highway was Burger King. I had a Whopper. I weathered it okay.”

Garcia’s clients tend to see him as a “best friend,” says Jason Binn, the 31-year-old publisher of Hamptons, Ocean Drive, and Palm Beach magazines. “He changed my life. You never know your body until you go to someone like Oz. I run around with the fastest people around, and my hours of sleeping and eating are crazy. He told me my whole life by analyzing my blood and hair samples. His objective is to level you out to where you’re just streamlined. He makes me do a cleansing once a week where all I eat is brown rice and vegetables and an ultraclear shake. It’s tough.”

Eating right might clear up the chronic-fatigue syndrome but not resolve a nagging knee problem from an old skiing injury. Some wealthy New Yorkers are so enamored of their chiropractors that they regard them as their chief source of medical advice. Chiropractor Wayne Winnick is one whose healing abilities have reached legendary levels. He calls what he does “holistic orthopedics” and says the best doctors should be as familiar with how the Incas treated pain as they are with the best modern surgical techniques. His clients include Condé Nast editorial director James Truman, fashion photographer Bruce Weber (who calls Winnick “truly a Dr. Feelgood in the natural kind of way”), entertainment lawyer (and Paul McCartney’s brother-in-law) John Eastman, Claudia Cohen, and Ron Perelman – to name a few.

Winnick defines holistic orthopedics as “anything to do with the body you can find a way to treat accurately without drugs or surgery.” His practice isn’t limited to traditional chiropractic methods. “The essence of our success is using all the modalities,” he says. “We do trigger-point therapy, transverse-friction technique, active release work. It’s like taking a steel ball and knocking down a building. Once you make the tissue changes, they are permanent. Once treated, they are cured, and they do not come back.”

Winnick, 43 and a New Jersey native, was schooled at the New York Chiropractic College. He has done postgraduate work in sports medicine and back pain at Harvard and also studied in China, where he learned Eastern methods for dealing with orthopedic conditions. His treatment of scar tissue, for example, comes from Chinese medicine, in which, he says, the first thing treated after surgery is the scar.

Most of his clients come in for sports-related injuries, knee pain, chronic pain, and accident-related problems. “I do a lot of knees before surgery,” he says. “I will put someone on a 30-day trial, so this way we can’t say we didn’t exhaust everything before surgery.”

“He gives you hope, and he gives you results,” says TV personality and Ron Perelman ex-wife Claudia Cohen. “Orthopedists invariably give you the same old stretch-and-ice advice; he understands pressure points. He gets tremendous satisfaction out of seeing his patients get better – and believe me, so many of his patients have been all over the lot for years looking for help, once they come to Wayne, they never go anywhere else.”

Joseph Weger, massage therapist to Ashley Judd, Blaine and Robert Trump, makeup artist Pat McGrath, and others too fabulous to list, makes house calls with his “essential healing oils” stashed in a black fanny pack. He arrives at my apartment talking about how Nostradamus’s apocalyptic predictions probably mean New York City is a goner around the stroke of midnight of the last day of this year. He totes his foldout massage table and oils, charging $175 for an hour and a half of trigger-point, deep-tissue massage using aromatherapy. He and his clients believe the combination of oils and his bodywork have preventative health effects, and that he can relieve sinus conditions, vertigo, and even prostate trouble.

Weger is short and stocky, with huge forearms and hands, a Marine haircut, and the body of a gymnast – which he was as a teen. Now 39, he took up massage therapy in the early nineties, studying first in California at the Institute of Psychostructural Balancing in Santa Monica and later at the Swedish Institute in New York.

Before giving me a demonstration of what the New York Post called “hands from heaven,” Weger anoints me with some of his oils. In minutes, I smell like a Greek Orthodox wedding mass, with basil oil (for tendinitis), a fourteen-oil combo (for harmony and balancing the energy centers), peppermint (as an anti-inflammatory), and eucalyptus (for respiratory relief). Finally he dabs some white angelica on my back, which he says has been proved through Kirlian photography to alter a person’s aura for the better almost immediately. He also says that certain oils applied to the soles of the feet travel to every cell of the body in twenty minutes. The massage is heavenly, but half a day and three showers later I still can’t shake the scent. On the other hand, I haven’t had the flu yet.

Donna Karan and Robin Quivers are a few of the devotees of Barbara Biziou, a ritualist who devises ceremonies for people who are grieving, terminally ill, or undergoing surgery, or who simply want prosperity and happiness. Biziou, a redheaded native New Yorker, also spent some time in California in the sixties and seventies, where she studied with a variety of spiritual teachers including Brugh Joy, a medical doctor and spiritual healer.

“What I do is in addition to Western medicine,” says Biziou, who sees many cancer and aids patients. “People need both medicine and healing rituals. Some people who have, quote, terminal illnesses say their quality of life is so much better, they have more energy, they feel calmer.”

A ritual, Biziou explains, can be anything from having a group of friends come over before surgery and give you gifts that represent their strong characteristics to writing down a wish and lighting a candle. It’s about focus and intention.

“With cancer patients, the first thing I teach is how to calm down, center, and relax,” she says. “We do breathing techniques that will immediately calm them down. Then we work out a ritual.” For one lawyer who had colon cancer, she created a healing stick and had him visualize his favorite place – a beach – by putting on suntan lotion and using lamps and ocean music. The lawyer brings the healing stick with him to his chemo treatments.

“Every house has nine energies,” says Alex Stark, a feng shui practitioner who uses geomancy to track down bad energy in houses and eradicate it. “What I do is like a CT scan, so you can say in this precise corner of your house the danger is greatest, and in this corner, you might want to put an altar to improve your relationships.”

Stark, who has a large, global client list, is half Peruvian and half Swiss and grew up in a family that was open to notions of South American magic and ritual. He studied architecture at Yale, but in his mid-thirties he had what he terms an identity crisis and began to use his gift – a gift that his fellow architects scorn, although he is respected enough that he teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design.

There are many feng shui practitioners working in New York (Donald Trump imports his from China), but Stark’s method is more intuitive and magic-oriented than most. He not only operates on feng shui principles of directions but says he physically senses the earth’s grid of energy. Where the lines of that energy intersect, migraines or damage to the immune system or other ailments can occur. Lay people cannot know whether their bed just happens to be situated on such an intersection.

Stark’s geomancy has enabled him, he says, to ferret out a “black stream” beneath the bed of a woman who had been diagnosed with lung cancer. He is much in demand at $250 an hour among the well-heeled who want make sure, for example, that they haven’t placed their bundle of joy’s crib over an intersection of bad energy.

Over lunch at Zen Palate, Stark offers to give me a quick Chinese astrological reading, which would be the guide for how he would rearrange my living quarters if I had the $250-an-hour fee. I give him my birth date, and he consults a tiny chart in his wallet, then tells me I am efficient and organized and have a good head for business. “You have a very strong potential for happiness and prosperity,” he concludes.

A guy who tells you that – and convincingly – is worth every cent of his fee. I can’t wait to scrape up the funds to have him check my apartment for black streams.