On a Tuesday evening in a dance studio on the fourth floor of the Spirit club, a “mind-body-soul” center in West Chelsea, a crowd of 90 women in belly-baring tank tops and yoga pants and men in baggy T-shirts and running shorts ready themselves for a workout. Some stretch their hamstrings, others mark their territory on the studio floor with water bottles. Everyone is barefoot, including the instructor, Jonathan Horan, 34, who looks every bit the tanned and fit surf bum he once was. “Hello, my loves!” he says as he begins the warm-up, setting the mood with Sarah McLachlan’s “Fumbling Towards Ecstasy” and encouraging his students to “move with the breath.” Some of his charges trace the perimeter of the room; others sway in place while taking deep, sinus-clearing inhales and exhales. After fifteen minutes, Horan gives them a new task—and this is where things get weird. It’s not knee bends or ab crunches or biceps curls he exhorts them to try. Instead, he tells them to pray: “Maybe it’s a prayer for your family, or a friend,” he says. “Or maybe it’s a prayer for yourself—that the outside is a better reflection of the inside.”

In the nineties, the yoga craze introduced New York’s fitnesscenti to the notion of mixing two practices that, to the Western mind at least, didn’t seem to go together: spirituality and exercise. Suddenly there was an alternative to pounding away vacantly on the StairMaster or running in circles in Central Park, one that whipped you into shape and reduced stress, yes, but also—bonus!—helped you merge with the universe. Now, after every permutation of yoga has been marketed, from Hot to Power to Disco, a new breed of fitness gurus—call them post-yogis—is taking the spirituality-and-fitness movement to the next logical step. They’re introducing classes that blend exercise with religious faiths from Judaism to Christianity to Native American shamanism to all-purpose “spirituality.”

The classes don’t make up a unified movement so much as an accidental subculture of loosely knit groups. Horan’s High Vibration Wave sessions mix a New Age vibe with vaguely Christian elements. Ari Weller, a personal trainer who grew up in a Conservative Jewish family, and Jay Michaelson, an Internet entrepreneur and Jewish scholar, lead a class called (ahem) Embodied Judaism. Rabbi and karate black belt Niles Goldstein takes students on outdoor-adventure excursions he dubs Outward Bound for the Soul. Parashakti Bat-Haim, a former modern dancer who has studied with Native American elders, offers something called Shamanic Earth Dance ceremonies. Even mainstream health clubs like Crunch are finding religion. Crunch offers Liquid Strength, a Zen-minded class, and it plans to introduce Gospel Aerobics in the fall.

This isn’t a Jazzercise-level craze—at least not yet—but interest does seem to be growing. Horan’s class, in its original space at the Children’s Aid Society on Sullivan Street, became so popular that neighbors complained about the noise and forced him to relocate. Weller and Michaelson, Goldstein, and Bat-Haim have all increased the number of sessions they offer or seen a rise in the number of students who attend their groups, and since 9/11, the number of spiritually related classes at Crunch, says fitness director Donna Cyrus, has increased by one-third.

Fitness-mad New Yorkers are always looking for the next new workout, of course, and in the age of multitasking, it never hurts to tick off two things at once. But the post-yogis insist something deeper is also at work. “A lot of us feel the spirit of organized religion has been lost,” says Horan, “so we’re searching for spirituality in different ways.” Cyrus simply puts it this way: “It’s like gyms have become the new churches.” Here, a guide to the new fitness temples.

High Vibration Wave

The instructor Jonathan Horan is a former child actor and adventure-sports junkie with the broad shoulders of Ben Affleck and the manic energy of Jack Black. He started teaching the Wave, a dance-based class, in his twenties, but didn’t realize it was his calling until he dislocated his knee in Snowbird, Utah. “It was a big mortality check,” says Horan, who grew up half-Catholic and half-Jewish, practicing neither. “It’s a cruel world out there, and this work feeds my faith in humanity. My dance is my connection to the divine.”

Where it meets In addition to his sessions at the Spirit club (Tuesday nights from 7:30 to 9:30; $15), Horan leads monthly Wave workshops at Exhale, on Central Park South (dates vary; $20). 212-760-1381 or ravenrecording.com.

Religious affiliation/philosophy New Agey with occasional Christian undertones. The Wave was invented by Horan’s mother, Gabrielle Roth, a revered wellness-movement figure. Her book Sweat Your Prayers: Movement as Spiritual Practice outlines the philosophy of freestyle dancing according to five different “rhythms,” or states of being—flowing, staccato, chaos, lyrical, and stillness—which make up the Wave. The goal, says Horan, is to focus on the dancing to “tap into the divine” and “release the chatter in your head.”

What it looks like Somewhere between a Baptist revival and a rave. Regulars refer to themselves as “The Tribe” and volunteer to assist Horan like dutiful altar boys. On one recent evening, they helped construct the class “installation,” a small shrine made of flowy drapes, votive candles, and a card with a quote from the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas: “If you bring forth what is in you, what you bring forth will save you / If you do not bring forth what is in you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” (On other occasions, the installation has featured rosaries, Buddhist statues, and goldfish.) After a quick warm-up, Horan starts to call out the rhythms. The one inviolate commandment, he informs newcomers, is don’t stop moving. “Even if you need a drink of water,” he says, “dance over to get it.” Unself-conscious types thrash around with abandon like Janis Joplin; more mellow souls sway slowly from side to side. One especially free spirit buzzes through the forest of bodies like some New Age Tasmanian Devil. Just when all the activity has made the studio nice and sticky, Horan pauses the music and calls his denizens to the shrine for a sermon. He asks them to consider how they dance in class. Are they shy? Afraid of their bodies? Judgmental toward others? The unspoken questions: What can that teach you about yourself? How can that help you grow? When he talks about a recent workshop he attended, he drops his voice to a whisper. He was so exhausted, he says, he could hardly move, so he decided there was nothing left to do but dance with God. “I just relaaaaaxed,” he says, opening his arms and letting his head fall back. It worked—he finished the workout with renewed vigor. “Maybe I was dancing with God,” he says. “Maybe I wasn’t.” Rapt students nod. Instead of Amens, there are deep sighs of recognition—and a few tears.

Physical benefit For slow dancers, the workout is modest. But for motivated types, it’s apparently considerable. “My abs are tight,” says Roger Kuhn, a musician, seminary student, and member of the Tribe. “And I have the best legs of anybody I know.”

Spiritual benefit Theo Kisch, 40, a painter who lives on the Upper East Side, goes to weekly Shabbat services at B’nai Jeshurun, but the Wave, he says, gives him something he can’t get from synagogue. By focusing on, say, his hips or elbows as he dances, he is able to “live in the moment” in a way that synagogue-going doesn’t foster. Dropping your inhibitions and dancing freely with a group of strangers, he adds, helps him “see the beauty in everything.” By the end, he says, “I feel in awe of everyone there.”

Embodied Judaism

The instructors Ari Weller, 34, and Jay Michaelson, 33. Weller is a former bodybuilder and celebrity trainer (P. Diddy was a client) who revamped his exercise philosophy after “too many clean-and-jerks” and the like resulted in a double hernia, a blown-out knee, and a torn rotator cuff. He integrated yoga and Pilates into his classes, then set about merging his day job with a renewed midlife interest in Judaism. With his graying beard and crocheted kipa, he could easily pass for a rabbi—if rabbis had ripped biceps and wore cargo pants. Michaelson is a writer and teacher of Jewish mysticism.

Where it meets Sol Goldman Y on East 14th Street in Manhattan (90-minute classes, dates vary; $25) and Elat Chayyim, a Jewish retreat in the Catskills (six-day retreats, dates vary; $300). Weller also offers private sessions at Fitness Results, a Flatiron-district gym (by appointment; $95). Embodiedjudaism.com.

Religious affiliation/philosophy Jewish, with a yoga bent—but not only a yoga bent (the subtitle of the class is “Not just yoga with a yarmulke”). Weller and Michaelson believe that when you combine Judaism with physical movement, it intensifies the effectiveness of each. “The religious community says exercise takes away from study,” Weller says. “But I say they’re lazy. If you study and exercise at the same time, it’s a double mitzvah.”

What it looks like Weller stands before a semicircle of mostly neighborhood locals who are outfitted in loose-fitting bohemian workout gear. As he leads the class through a Gyrotonic-style warm-up (gently tapping every body part from head to toe to promote circulation), followed by some Pilates-style core work and a bit of yoga, Michaelson provides the Kabbalistic interpretation of the movements. While the class does upper-body work, Michaelson draws the Sefirot, the Kabbalistic map of the body, on a white board. He points out Hesed and Gevurah, the energy on the right and left arms, respectively, which symbolize loving-kindness and judgment. The point is to make the students aware of the concepts associated with the various body parts so that they might understand their humanity more fully. “The body is the metaphor to understanding the map of the soul,” says Michaelson. After taking his class, he notes, “you also start to understand Madonna songs better.”

Physical benefit It’s like a good yoga or Pilates class: a lot of lengthening and strengthening, without a lot of bulking up.

Spiritual benefit Michaelson says he wants students to build a fresh understanding of God through the body: “This is the God we’re interested in, not the story of some man sitting on a throne.” That seems to work for Nick Dine, an interior designer who lives in the West Village. “I have an aversion to organized religion. I’m interested in spirituality as a personal journey,” Dine says. Weller, he adds, is like a healer—“and kind of like a rabbi. But he doesn’t proselytize. I get spirituality by osmosis.”

Outward Bound for the Soul

The instructor Niles Goldstein, 38, a brawny, stubble-faced rabbi with a black belt in karate.

Where it meets Could be anywhere. Sometimes Goldstein takes members of the New Shul, the progressive synagogue he co-founded in Greenwich Village, on day hikes upstate (no charge); other times, he leads groups on dog-sledding treks in Alaska (prices vary). He also leads retreats at Elat Chayyim and the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck (from two to seven days; $300 to $500). 212-284-6773 or newshul.org.

Religious affiliation/philosophy His days of college rugby behind him, Goldstein took up martial arts when he was studying to be ordained as a way to keep in shape, and to provide an outlet for his aggression (his book, God at the Edge, begins with him in jail for ripping a urinal out of a nightclub wall). Along the way, he discovered that his karate lessons mirrored his spiritual training. “How do you build muscle tissue?” he asks. “You break it down first. You can apply that same dynamic to our souls.”

What it looks like Extreme sports, Jewish-style. The activities themselves are no different from the usual outdoor adventures. What distinguishes them are the lessons. Last October, Goldstein led a group of college students on a rock-climbing expedition in Boulder, Colorado, in which their lives depended on their partners’ ability to hold their safety ropes. After the climb, Goldstein brought out a text from the Talmud that dealt with the importance of trust. “They said, ‘Wow, this 1,500-year-old text that I thought was completely irrelevant to my life is actually incredibly contemporary.’ It taught the same message they just learned climbing that mountain face: that we are all interconnected.”

Physical benefit Your grandma could handle Goldstein’s day hikes, but the Survivor-type endurance tests demand, and build, peak physical fitness.

Spiritual benefits “I’ve sat in some services and thought, ‘I just want to get out of here,’ ” says Jamie Skog, a 20-year-old student who took part in the Boulder expedition. “Goldstein teaches you that God is everywhere, not just in a synagogue.”

Shamanic Earth Dance

The instructor Parashakti Bat-Haim, 29, a former modern dancer trained in shamanism by Native American elders.

Where it meets Yoga studios including Be Yoga (two hours; $15) and Healthy Yoga (five hours; $35). Once a month, Bat-Haim leads a ceremony at an all-night alternative-movement marathon called Body Temple, where participants number in the hundreds (locations vary; $40). Bat-Haim also does house calls for private clients ($125 for 90 minutes). “Have you ever heard of the Heinz family?” she says. 212-501-3760 or parashakti.org.

Religious affiliation/philosophy Bat-Haim grew up in Tel Aviv but doesn’t consider herself connected to Judaism—or any specific religion. She describes herself as spiritual “in the universal sense.” “Earth Dancing,” she says, “is a way to get connected back to the body, soul, spirit, and God.”

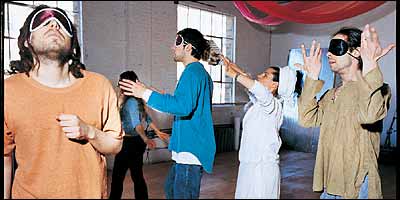

What it looks like Martha Graham meets blindman’s bluff. Class begins with a multigenerational mishmash—everyone from 15-year-olds who arrive in rave gear to an elderly pair of regulars from Queens—standing in a circle, holding hands, and giggling nervously. Dressed in a white blouse and flowing white skirt, Bat-Haim and four assistants stand in the middle. Bat-Haim holds a roll of burning sage leaves in one hand and a black-and-beige owl wing in the other. She belts out a series of “Hey ya” tribal chants that sound like the OutKast lyric. Velvety blindfolds are handed out. As her D.J. (and boyfriend), Fabian Alsultany, spins a selection of tunes he calls “National Geographic on acid,” the blindfolded participants start dancing. As they whirl about, Bat-Haim instructs the students on “shaman’s breath”—two inhalations through the nose and one long exhalation out the mouth to rid themselves of “mental and physical blockages.” They don’t stop for an hour—or six, if it’s one of Bat-Haim’s intensive workshops.

Physical benefits The two-hour-long sessions give a good aerobic workout. The six-hour jobs are an all-out endurance test.

Spiritual benefits Being blindfolded, says Doug Larson, a 26-year-old health counselor from Jersey City, “you can hit your fears head-on and look at your soul.” He’s also partial to the shamanic breathing. “You get a high from it. It lifts you to a spiritual place.”

Liquid Strength

The instructor Elizabeth Story, a sculpted blonde who has been teaching fitness classes and modeling (she was on a Jogbra box) for fifteen years. Story was raised Presbyterian, but as she got older, she lost interest in organized religion. In her classes, she says, she tries to help people, especially women, feel good about their bodies. “Bodies are miracles,” she says. “Look at what your body can do!”

Where it meets Crunch, multiple locations (Mondays at 9:15 a.m., Tuesdays at 12:30 p.m., Wednesdays at 9:30 a.m. and 6:30 p.m.; $24, free for Crunch members). 212-769-7136 or liquidstrength.com.

Religious affiliation/philosophy “Hyper Zen” is what Story calls it. Gyms like Crunch are apprehensive about overt religious overtones, hence the focus on bodies, not Bibles.

What it looks like A Method-acting workshop with hand weights. Each participant (most are refugees from spinning and yoga) has the usual pile of weights and body bars. But instead of merely leading students through drills, Story turns the activities into role-playing exercises. Wielding their body bars, the students become ancient warriors. Or they paddle up the Amazon, focusing intensely on each stroke. The movements are slow, methodical, and purposeful, the music soft and wordless. The idea, again, is to enter the realm of the spiritual through deep concentration on the physical (Story likens her method to Transcendental Meditation). Or perhaps this explains the appeal: “Your mind is so consumed with your task,” says Story, “you forget your body and you don’t feel the work.”

Physical benefits Roughly approximate to a body-sculpt class, accentuating the core and the butt.

Spiritual benefits “I’m a spiritual thinker,” says Elena Caffentzis, a 31-year-old speech therapist who attends Liquid Strength twice a week. “I was raised Greek Orthodox, but I feel like God is in everybody. What I feel when I’m in this class makes me appreciate what God gave us. I’m in awe of who invented us.” So much the better, Caffentzis says, that if in the process of being awed, “my clothes are bigger. And the class really works your glutes.”