Hey, I’m Eric Forman,” says the grinning, floppy-haired waiter bounding up to Topher Grace in the lobby of the Mercer Hotel.

“Oh, I’m sorry, man,” says Grace, polite but virtually expressionless as he shakes the hand of a guy with the same name as the droll stoner he plays on the sitcom That ’70s Show. “That must be … bad.”

“No, no—it’s great. I like it!” Forman gushes. “It’s been a lot of fun. I’m kind of like him. My friends all call me Forman, like him. My name’s spelled the same. I was in the Ukraine, I told this guy my name, he says, [affecting an accent] ‘Ah! Forman! Like That ’70s Show!’ ”

“That’s … weird,” Grace says, all skinny arms and pointy elbows in a preppy white T-shirt and jeans. “Well, great to meet you, man.”

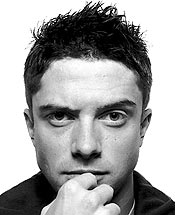

Grace is utterly courteous, if slightly bemused—not exactly thrilled to meet another fan of That ’70s Show, but hardly upset, either. It’s a tense time for an ambitious young actor who, like the waiter, was only known as Eric Forman until very recently. But this spring, the 26-year-old Grace will graduate with what amounts to a Ph.D. in situation comedy, after six corduroy years on the popular teen show. So far, Grace has made careful moves, taking a strong bit part in Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic and a forgivable lead in the glossy Win a Date With Tad Hamilton. And he’s held out for roles like the lead opposite Laura Linney in this past summer’s underrated indie P.S., in which he nailed the part of a horny, egomaniacal Columbia University art student. In interviews, he defers talk of romance, speaking diligently about hard work and ambition. And five times during our conversation, Grace refers to how “green” he is, displaying a striking self-awareness of the pitfalls awaiting a TV actor crossing over into movie stardom—how a choice role can launch the perfect career (George Clooney, Out of Sight) or typecast you for years (Ashton Kutcher, Dude, Where’s My Car?).

Grace has even been smart enough to preempt “It”-boy critiques by parodying himself in Steven Soderbergh’s recent caper flicks. In Ocean’s Twelve, reprising his role as a young Hollywood prick named Topher Grace, he bumps into Brad Pitt and ER alum George Clooney. “I hear it’s hard moving from television to film,” says Pitt. Grace retorts, “Nah, man, it’s easy … I totally phoned in that Dennis Quaid movie.”

Of course, Grace did nothing of the sort. In Paul Weitz’s In Good Company, Grace gives a brilliant performance as the young boss of Quaid’s grizzled ad vet: He’s boyish and cruel and calm and crazy, often all in the same, seemingly flat expression. “I think Paul is our Billy Wilder; I’d be thrilled to be his Jack Lemmon” is the great line Grace has been telling reporters like me—and it fits. For those slight upturns of a lip and those controlled jitters—a peculiar alchemy of big-city bravado and New England manners—the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures just awarded him their Breakthrough Performance award, and NBC invited him to host Saturday Night Live.

Grace fought hard for the role of a character who worries that his “life has peaked at 26.” An overcaffeinated, stressed-out, ambitious Manhattan ad salesman, Grace’s Carter Duryea anxiously overcompensates for his own inadequacies and, eventually, falls for his elder’s NYU-student daughter (Scarlett Johansson). “I said, ‘You can’t give this role to the five more famous guys who should get it,’ ” recalls Grace. “ ‘They all grew up in Los Angeles. I grew up in Northeastern boarding schools.’ I said, ‘This is a language you have to speak. It’s my first language.’ ” That language is a mixture of “awesome” dorm-room jargon and dot-com Dale Carnegie–isms—delivered with a “thriftiness of emotion,” says Grace, joking that “Get psyched! is my Show me the money.”

Like Jack Lemmon—another tart Wasp actor with a deft touch at dry comedy and a barely hidden mean streak—Grace was born in New England, the son of a successful businessman. Lemmon’s father was a doughnut-company executive, while Grace’s father, John, is a veteran of Grey Advertising, the former executive director of Interbrand, and is currently chief executive at the “brand-management consulting firm” Brand Taxi.

Grace defers talk of romance, speaking instead of hard work and ambition Five times during our conversation, he refers to himself as “green.”

“The script for In Good Company was the first one I ever showed my dad,” says Grace (who notes that there wasn’t “a lot of excitement in the house” when he landed his sitcom). “He’d been in a company that had been taken over by Omnicom or something—our fake company that does the takeover in the movie is called Globecom. That’s when he left and formed his own company.”Grace says he and his father talked about takeovers—and “about how the young eat the old now, the youth-worship.” Grace smiles, just a slight twist of the lip. “My dad would always say to me, ‘Having more energy doesn’t mean you’re smarter.’ ”

So has his father offered up his services?

“Has he done my brand identity? No,” says Grace, with that sliver of a smirk again. “I can’t afford him.”

Even so, Grace seems to have the image—smart, serious, committed young actor—down pat.

“C’mon, it’s not brain surgery. To be a smart actor is like—I shouldn’t say that—what my dad’s helped me with is, he’s the guy who gets up every Sunday at 8 A.M. to do chores.”

But Grace says his father taught him to handle the stress of stardom the way most New Yorkers handle the stress of their jobs: by diving in and taking on more. He says overload is his secret—that’s why, on his week off from the TV show, he’s doing this interview, then hustling into rehearsals to host SNL. That’s also partly why he filmed 25 television episodes and three movie parts in one year.

“I certainly like working harder than a lot of my peers,” says Grace. “The trick is embracing it. When you work so much, you actually do better work—because you don’t have time to endorse all that ‘I’m nervous’ bullshit.”

That, too, is in the blood.

“I remember calling my dad from the set of In Good Company and telling him, ‘This is tough. I have to get up at six, put on the suit,’ and he says, ‘Hey, jerk. That’s my life.’ ”

At the end of In Good Company, Grace’s overanxious character finds some peace—by leaving the city. “I’m great. I’m in Los Angeles” are some of his last words (spoken into a cell phone, of course). But in March, Grace is reversing the commute to keep sane. “It’s like a breakup,” he says. “You want to move out of town and start over.”

He’s bought a West Village apartment and will begin to sort through the new—and, likely, better—job offers coming his way. He’s going to take it easy, too. Travel (“On my own terms, not on a junket, or with the fam,” he says). He just got a dog. And his sister bought him cooking lessons in the Village.

“I just want to spend the next couple of years not going too fast, waiting for the right projects,” he says, shortly after Famke Janssen drops by the table to say hello. “Then, when that career bombs, I can go back and do That ’90s Show.”

Five minutes later, he’s talking about the laundry list of directors he’d love to work with: Guillermo del Toro, Michel Gondry, Sofia Coppola, Linklater, Zemeckis, Spielberg. Green? Maybe. But right now Grace sounds more like a true New Yorker, talking about taking it easy one minute—then passionately planning to take over the world the next.