When Mel Brooks walks into a room, you can be sure he will say something funny, even if the room is full of Nazis.

This particular room—an enormous soundstage at Steiner Studios in Brooklyn’s old Navy Yard—contains precisely 54 Nazis, or, to be more specific, 54 chorus boys dressed in tight-fitting storm-trooper costumes, with shiny metallic helmets, and arranged in a giant dancing swastika. At their center stands Uma Thurman. Her head is resting on Hitler’s shoulder.

Brooks watches the scene from a canvas director’s chair off to the side; at 79, he looks a bit like, and has the commanding presence of, a comedy Yoda. (He did, in fact, play Yoda in his Star Wars parody Spaceballs; or, rather, he played “Yogurt.”) So when he launches into a story, everyone around him stops and listens. And Brooks is full of jokes, each delivered with the honed cadences of a lifelong showman. He explains that, during an early staging of The Producers, “a Jewish guy got up and stormed out of the theater. He saw me standing at the back with my wife. He said, ‘This is an outrage! I fought in the Second World War!’ I said, ‘You served in the war?’ ”—and here he stops, takes a beat, then pounces on his punch line—“ ‘So did I. I didn’t see you there.’ ”

By all appearances, this is a perfect day to be Mel Brooks: His jokes are landing, his audience is laughing, and the most famous scene from his Broadway show, the thrilling pinnacle to his life’s work, is being immortalized around him on film. If you’re among those eighteen or so New Yorkers who are unfamiliar with The Producers—both the original 1968 movie and the Broadway phenomenon—here’s the basic plot: Two Jewish producers, the bombastic Max Bialystock and the simpering Leo Bloom, conspire to make millions by mounting the biggest flop in theater history. Springtime for Hitler (A Gay Romp With Adolf and Eva at Berchtesgaden) is the offensive disaster they unearth, in hopes that it will close opening night and they can abscond with the millions of dollars Bialystock’s raised by seducing randy old-lady investors. The Producers unfolds in a barrage of broad gags and Borscht Belt groaners, but the “Springtime” sequence—with its fey, crooning Hitler and the kick line of menacing Aryans—marks the moment that the show transforms into something greater, from a slapstick musical to comic genius.

The number also beautifully illustrates one of Brooks’s favorite maxims: what he likes to call “ringing the bell.” When he was directing Blazing Saddles in 1974, he fretted to producer John Calley about a scene in which an old lady gets punched. “Can I really beat the shit out of an old lady?” he asked. “Mel, if you’re going to go up to the bell, ring it,” Calley replied.

Until now, the story of the Broadway production of The Producers has been one of triumphs on top of triumphs, a Hollywood ending that’s refused to end. By the late nineties, Brooks’s productivity had petered out; he hadn’t had a hit since Spaceballs in 1987, and his previous two films, Robin Hood: Men in Tights and Dracula: Dead and Loving It, left even his most ardent fans worried that his skills had finally failed him. But in a last-minute twist, Brooks reemerged as a Broadway impresario, delivering a retro romp that came off as strikingly fresh. There was a poignancy, to be sure, that this late-career success was a reworked version of the cult movie that had launched Brooks as a director—and that now that old story had given him new life. (Like many people, when I first heard Brooks was planning a Producers revival, I felt a twinge of embarrassment, not excitement.) But The Producers was irresistible, like being tickled mercilessly by a rascally uncle. It broke box-office records, won twelve Tonys, and left a trail of rapturous reviews, which doubled as excited declarations that the king was back on his throne.

Most of all, the musical was a near-flawless collaboration between Brooks and an artfully assembled team he’d personally courted and conscripted, just as Bialystock gathers his own troupe in the show. Brooks wooed Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick, who became famous for their onstage chemistry. For his director and choreographer, he approached the well-regarded Broadway veterans (and husband and wife) Michael Ockrent and Susan Stroman. They got a call one day in 1999 from one of Brooks’s assistants, asking them for a meeting. An hour later, Mel Brooks himself knocked on their door. He didn’t introduce himself but instead launched into a full-voice rendition of “That Face,” a love song from the musical, then danced down the hallway of their apartment, before hitting his big finish by leaping on their couch. “Hello,” he said finally. “I want to make a musical out of The Producers, and you’re the people I want to help me.”

In December 1999, however, Ockrent, who had been ill that year with leukemia, died. After Stroman took a two-month break, Brooks asked her to step up and direct. The assignment wasn’t totally unexpected: Stroman was directing two shows at the time, Contact and The Music Man, both of which premiered in the spring of 2000. Initially, Stroman wasn’t sure she could continue, but Brooks and his co-writer, Thomas Meehan, urged her to get back to work, in part because they knew it was the best way for her to deal with her grief.

Like the odd-couple pairing of Bialystock and Bloom, Brooks and Stroman turned out to be a perfect complement: Brooks was the Borscht Belt genius who’d never staged a Broadway show, and Stroman was the Broadway talent with little experience in comedy. So Brooks brought the gags, and Stroman brought her eye for dazzling set pieces and clever stage play, such as the moment when long-legged showgirls step out from filing cabinets during a Bloom fantasy sequence, or the outlandish number in which little old ladies do a tap dance with their walkers. Despite its cinematic origins as an acidic, zany satire, The Producers has always been, at its heart, a love note to great musicals—and together Brooks and Stroman turned that note into the real thing.

So when it came time to make a movie of the musical, Brooks wanted Stroman. It didn’t matter to him that she’d never directed a film before, let alone a lavish, old-school musical full of extravagant sets and complex production numbers. He was determined to keep his original dream team intact. (With two exceptions, at the studio’s insistence: Will Ferrell and Uma Thurman were drafted to play Franz Liebkind, the Nazi playwright, and Ulla, the leggy Swedish secretary.) Nor did it matter to Brooks that, despite its Broadway pedigree, the movie was not a guaranteed hit. For starters, The Producers hasn’t toured as well as expected. Productions in Toronto and Australia closed early, and even a version in Los Angeles starring Martin Short and Jason Alexander had trouble selling out. And unlike, say, The Lion King or Mamma Mia—spectacle-heavy, plot-light shows for which an audience doesn’t even need to speak English—The Producers is verbal, manic, Jewish, and very, very New York. The show’s met with mixed reactions in other parts of the country—especially a line delivered by Nathan Lane in the opening number, “The King of Broadway.” He stands on a garbage can, shakes his fists to the heavens, and translates the Yiddish words of his mentor: “Who do you have to fuck to get a break in this town?!” In New York and Chicago, it got big laughs. In Pittsburgh, however, it drew only a gasp, so Brooks and Meehan changed it temporarily to “shtup.” (Lane also said “shtup” in a command performance in London: “You can imagine how well that went over with British royalty,” he told me.)

Even Brooks was worried about the line in early rehearsals. “We can’t say fuck in a musical!” he told Lane. But Lane—who’d come up with the line—reminded him to ring the bell. “I said, ‘Wait a minute? Have we met? You’re Mel Brooks!’ ”

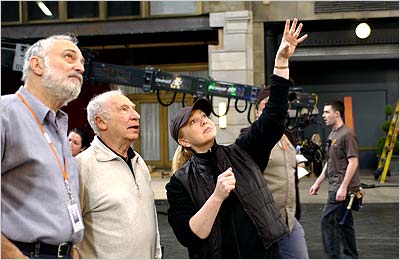

On a soundstage at Steiner two months into filming this summer, Susan Stroman is wearing the same outfit she wears every day on set: black sneakers, black warm-up pants, a black zip-up jacket, and a black baseball cap, with a long blonde ponytail dangling out the back. No one calls her Susan; everyone calls her Stro. She’s not a tall woman, and in the constant swirl of technicians, assistants, actors, onlookers, dancers, stagehands, and friends who mill on the darkened soundstage, you’d be hard-pressed to pick her out as the ringleader of this $50 million production. As a scene plays out, she leans in closely to watch the action on the video-assist monitor, grinning at each joke, mouthing the lines along with the actors, and waving her hands frantically as though trying to conduct them from afar.

Stroman, who is 51, is warm and approachable, greeting me with a kiss on the cheek each time I arrive. When I ask Meehan, who spent nearly every day on set, how Stroman gets what she wants as a director, he laughs and says, “She could charm the birds out of the trees.” Over the course of the filming, she explains to me that making this film is the culmination of a dream—the opportunity to make just the kind of musical she loved as a girl growing up in Wilmington, Delaware, where her salesman father would play show tunes to her on the piano. She has a savant’s knowledge of old movie musicals—Singin’ in the Rain, The Band Wagon, Royal Wedding—that inspired her to move to New York to become a dancer and then a choreographer. She even went so far as to invite the director of Singin’, Stanley Donen, now 81 years old, to stop in and visit the set. “I thought this kind of genre was over,” she told me. “I feel like I was meant to direct, but not just any movie—a movie musical.”

A month into the shoot, the Post’s “Page Six” ran an item chronicling rumored strife on the set between Stroman and Brooks. “Our source claims the comedy legend is not entirely impressed with the work of first-time director Susan Stroman … and has reshot ‘scene after scene,’ ” the item read. There had been tension when the original cinematographer was fired and replaced. But when I ask Stroman about the rumors of conflicts with Brooks, she bristles. “I’ve never once fought with Mel,” she says. “Ever.” According to all involved, there was another explanation for the rumors. Brooks wasn’t angry; he was absent. On the first day of shooting, his wife, Anne Bancroft, was admitted to Sloan-Kettering, gravely ill with cancer. So Brooks was splitting his time between the set and being with her in the hospital. Stroman believes his absences—the reason for which only she, and a few others on set, knew about—may have stoked the gossip. “That upset both of us, but we couldn’t say, ‘No, he’s not here because he’s at Sloan-Kettering.’ ” In fact, she says, the parallel between their experiences drew them together. “When I first met Mel, my husband was sick, and now the exact same thing was happening to him. So we were very close during this time. He didn’t want anyone to know Annie was sick. So the only person he would tell the truth about what was happening was me.”

The situation took a mounting toll on Brooks. “Originally, the idea as we’d talked about it was Susan was directing and Mel would be around,” Meehan, the 73-year-old co-author of the screenplay, told me. “With Mel’s experience of making so many films, over 30 years in filmmaking, he would always be a help to her if she needed it. But the way it worked out, Mel was not able to contribute as much as he would have otherwise.” Later, Meehan said, “I tried to some degree to be a surrogate for Mel. But I’m not a movie director. It was a very friendly, easygoing shoot. Sometimes the content was a little off or they were missing the readings. So I’d go over and talk to Stro, and almost every time, she would reshoot.” When Brooks was able to visit, as he would whenever he could, there would be a notable hubbub among everyone present. His spirits, to an outsider, seemed high. He’d reliably crack wise—“The stage show just opened in Argentina! Can you believe it? It’s like a Bialystock and Bloom joke!”—and, if anyone fussed over him too intently, he’d wave them off. “I’m okay,” he said one day to a determined handler, while settling into his chair. “I’m not saying ‘cut’ or ‘action.’ I’m okay.”

If anything, whether or not Brooks was there during my visits, the production hummed with the friendly air of a summer-camp reunion. Not only were Broderick, Lane, Gary Beach (as the gay Hitler) and Roger Bart (as Beach’s assistant) all playing the same roles they did onstage, but nearly everyone, from the chorus girls down to the stand-ins for Broderick and Thurman, had performed in The Producers, either on Broadway or in a touring company. “One nice thing is that I never had to learn any lines,” Broderick joked of the familial atmosphere. Then he said, “My only worry was, since it was so comfortable, that I would phone it in. That it would be too comfortable.” These players, after all, had worked together, doing the same show, with the same jokes, for nearly six years. And though they are unceasing in their praise for Stroman’s direction, she had never before been charged with commanding an entire film production. The stereotypical notion of a film director is that of a unyielding dictator, but Stroman was anything but. In fact, at times she seemed at loose ends as to how to get precisely what she wanted.

During the filming of a dance sequence as part of Broderick’s “I Want to Be a Producer” number, she watched the monitor, then grimaced. Broderick was supposed to run along a line of chorus girls dressed in $9,000 beaded costumes, pinching their asses as he goes. But on the first take, he merely flicked at their behinds. Stroman called her assistant choreographer over. “Tell Matthew to really go for it,” she said. “Make the pinches real.” He relayed the message, and they shot another take. At the moment of truth, though, Broderick flicked at the asses again. Stroman told me later she thought that Broderick may have had trouble with the tricky maneuver. On set, though, she clearly wanted him to deliver more. She pulled her assistant aside. “Matthew didn’t—” she said, then made sharp lobster pinches in the air. The assistant strolled back toward the set. “She’s not happy with the pinches,” he announced. The assistant director chimed in with a mock German accent: “Ze pinches must be correct!”

They reset for another take. Again, Broderick went through the motions, with nary a lobsterlike grasp in the bunch. Stroman watched the monitor; her face fell again. She seemed frustrated, as though trying to untie a knot. The lunch break was looming. At this point, I thought she might pull him aside to ask for what she wanted. Instead, she turned to the assistant director and asked, “Could we do one more?” They reset the shot. Again, Broderick flicked at the bottoms. Stroman called cut, then pulled her headphones from her head. “We’ll get it in another shot,” she said, and the cast and crew broke for lunch.

Later in the summer, after filming had wrapped, Brooks arrived at a midtown soundstage where Stroman was working on some last-minute music edits for the cut they were preparing for the studio. Bancroft had died a few weeks earlier, and when Brooks entered, the room quieted. Stroman rose from her chair to greet him and gave him a hug. “Hey, Mel,” she said. He smiled and said, “So, what did you make today?”

Then Brooks, who started his career as a drummer in the Catskills, started tapping a tattoo on the back of Glen Kelly, the show’s musical arranger, standing nearby. “Do you know what that is?” he asked. “It’s the opening bars from Gene Krupa’s ‘Sing Sing Sing.’ ” Then he said to the room, “When this film opens in Germany, let me know. I’ll be in Brooklyn. Call me and let me know how it goes over.”

His manner—kidding, smiling, nailing the punch lines—recalled a day during the filming when Stroman enlisted him for a surprise cameo. In it, he appears in a tux and a fedora to sing the climactic line to a song. He posed on a glittering stairway, surrounded by beautiful showgirls, each of whom seemed giddy and slightly hesitant to be crowding the comedy legend. “Closer, closer!” Stroman instructed them. Then she called action and the camera rolled. The set fell silent. Brooks delivered his punch line, again and again, belting it out, in a dozen different variations. It felt as though he were conducting a master’s class in just the kind of comic timing that, in reality, can never be taught. I asked Stroman about it later. “He had a good two hours there,” she says. “He gave a hundred percent, full out. Then he went to Sloan-Kettering.”

Since The Producers wrapped, Brooks has withdrawn in California. The film, which started as an effort to preserve a career-topping triumph that all of them had shared, has, for Brooks, been consumed by a larger shadow. He did a couple of interviews to promote the film, then canceled the rest of his press. By e-mail, he said, “Susan did a magnificent job. She invented incredible movements and moments, and she was very loving with Nathan and Matthew. No one has ever, including Gene Kelly in An American in Paris and even Singin’ in the Rain, done better production numbers than the ones that Susan Stroman has done in this film. Stroman was born to do it.” He’s hoping to travel to London to do press for the film there, but for now, he’s avoiding all public appearances.

“Mel has been through the worst year of his life,” Meehan told me. “I spent quite a bit of time with him all last summer in New York and then out in California. We’re sort of working”—they’re sketching out a new project, a Young Frankenstein musical—“but I’m also like his grief therapist. It’s been very difficult for him.” When Stroman lost her husband, “she thought she’d never work again,” says Meehan. “Which is what Mel first said: ‘I’ll never work again.’ ”

The film’s gala New York premiere was scheduled for a Sunday in December at the Ziegfeld. It’s the first time Broderick, Lane, Stroman, and Meehan would be together to watch the finished work. Brooks, however, would be staying in California. He’d decided he couldn’t attend.

Stroman’s midtown office, just south of Columbus Circle, is a stark contrast to her familiar black uniform: The office is white, all white, with white leather furniture and a white board table with white chairs, the whole setup reflected infinitely in a room surrounded on all sides with mirrored walls. We met there in late November, and she was no longer wearing her trademark black. She wore a faded denim shirt, and her long blonde hair, freshly washed, hung loose. She’d just returned from L.A., where she’d wrapped a final bit of editing on the film.

“As Kander and Ebb say, it was a quiet thing,” she said. “When I finished, I walked out into this big empty parking lot, drove back to the hotel, and went to bed. In the theater, everybody’s in the pool, and you either drown together or you get an Olympic medal together. And you’re always celebrating something. You celebrate the last day of rehearsal. You celebrate the first preview. You celebrate opening night. It’s not that way in film. It is hard work, technical work. It was a very different feeling.”

The film version of The Producers opens in New York on December 16 and then rolls out to the rest of the country on Christmas Day, buoyed, if all goes according to plan, by good reviews and positive word-of-mouth. In part, its success will rest on whether America’s multiplexes are hankering for a broad comedy in the style of the old-fashioned musicals that Stroman’s always loved. But the movie, too, has been modified for the multiplexes. Unlike the stage version, which leavened its groaners with audacious raunch, the film feels more like a big blown kiss to a bygone genre, less a strenuous preservation than an affectionate cover version, cleaned up for heartland families. “We have the word shit in the opening song,” says Meehan, “and that’s our only four-letter word in the whole movie.”

Lane, in particular, shines in his manic star turn, and the leads are all so proficient—yes, even Broderick—that in their hands, the film whiles away an entertaining two hours. But it’s a different experience than the stage show, drained of just enough of the original’s recklessness that, at times, you feel like standing up in the theater and shouting, “Wait a minute? Have we met? You’re Mel Brooks!”As for Nathan Lane’s who-you-gotta-fuck, bell-ringing opening line—which Stroman had asked him to change during filming, a request he flatly refused—the matter turned out to be moot: The entire “King of Broadway” opening song was cut after a test audience responded well to a version without it. And the changes seemed to have worked: That preview screening, in Edgewater, New Jersey, drew wild applause, and the response cards were even more positive than the studio had hoped. The show that had once drawn gasps in Pittsburgh now got near-universal praise. “The market-research guy told us it was the best response they’ve seen since Forrest Gump,” Meehan says.

One day during the shoot, I’d asked Stroman what, of all the assorted bric-a-brac scattered on the various sets, she planned to take home as a souvenir. “The marquee for Funny Boy,” she said, referring to a large lit-up sign advertising a mock-musical version of Hamlet. “I’m going to put it on my wall.” Funny Boy is a classic, shameless Mel Brooks gag—along with She Shtups to Conquer, South Passaic, and A Streetcar Named Murray—and glitzy Funny Boy signs hung all along the film’s elaborate re-creation of 44th Street. So even when Brooks was absent from the shoot, his punch lines hovered in the sky, spelled out in lights. Between shots, Stroman would stop to gaze at the signs. “There’s something about staring at the word funny that’s good for the soul,” she said. “So when we were on 44th Street, I’d just stare at that word: Funny.”