For many of us, Bill Murray hit his career peak in Lost in Translation, two years ago. Playing an emotionally exhausted middle-aged film actor whose sense of unironic wonder is reawakened by a flirtation with Scarlett Johansson, Murray was an idealized surrogate (that’s one definition of a movie star, isn’t it?) for lots of men and women who’d grown up laughing our asses off at him in Caddyshack, Ghostbusters, and Groundhog Day, on Saturday Night Live and Letterman. Murray was also startlingly moving in Rushmore, his warm-up for what he pulled off in Translation, and even the quick reaction shot of him at the Oscars, witnessing his loss for the latter film, was a lesson in muted stoicism. But his role in last year’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou was too broad—the most Murray could do in director Wes Anderson’s cleverly off-kilter but excessively thought-out film was to cross Buster Keaton with Peter Sellers, an ungainly combo for any actor.

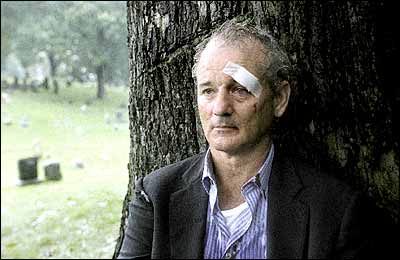

Now, working with director Jim Jarmusch in Broken Flowers, Murray manages, almost impossibly, to come up with still another rich variation on his Depleted Man persona, and his performance is at once enormously generous and fiercely, concisely witty. Murray plays Don Johnston, an independently wealthy mope who made a killing in computer technology and now spends his days alone in his sleekly empty home, listening to classical music and perfecting his lack of affect. His only other pleasure seems to derive from friendships with his next-door neighbor, Winston, an Ethiopian man played with wily charm by Jeffrey Wright, and with Winston’s boisterous family (as usual, Murray + children disproves the old showbiz saw about not acting with kids: This is one guy who loves to be upstaged by them).

One day, Don gets an unsigned letter from a woman, a former lover, telling him he has a 19-year-old son. Prodded by Winston (who’s vicariously intrigued and knows his friend needs adventure in his assiduously dull life), Don sets out across the country to visit four former flames to figure out who, if anyone, made him a father. Jarmusch, who also wrote the film, uses movie genres (the Western in his woefully underrated Dead Man; the samurai film in the cult favorite Ghost Dog; the road picture here) without doing that now-trite thing—“subverting” them. Instead, he brings a surprising sincerity to the picture’s various familiar tropes.

The film’s journey-quest structure also lends Flowers some distinctive suspense. In each case, as soon as the door opens, you wonder, What did he ever see in her? And by the end of the scene, the answer is clear—it’s one mini-revelation after another. Sharon Stone, playing a widow who’s half-hippie, half-working-class-tough, demonstrates that, given the right part, she’s still not merely sexy but knockabout funny and sly. I’m not telling you how much info about his theoretical son Don extracts from each woman, but next up is Frances Conroy, doing a slight variation on her neurotic mother in Six Feet Under. She’s the most poignant of Don’s former attachments (now an uptight suburbanite, but once a dreamy girl), and soon he’s on to Jessica Lange, whose character could have been unbelievable—an unconventional therapist, an “animal communicator.” Lange imbues her with such earnest conviction, however, you end up liking her, even as Murray’s skeptical raised eyebrow is given a vigorous workout. Don’s final stop on his road trip is to see Tilda Swinton as a raging biker, in what amounts to a vivid cameo.

Broken Flowers relies on Bill Murray’s persona, but it also turns that persona back on him. Instead of maintaining the satirical distance that made it easy to laugh at heartland eccentrics in, say, Alexander Payne’s About Schmidt, Jarmusch’s film avoids caricature, and Murray’s poker face melts. Don feels a bittersweet regret at becoming exactly the sort of granite-faced wise guy Bill Murray has made his rep at enshrining. Murray is at a point in his career when his self-effacement has achieved high comic art, and he collaborates with Jarmusch at a point in his career when he’s trying to be something more than hipster-serene. Both succeed, by committing to the notion that a yearning to be reborn within a hopeless, brittle soul is worthy of drama—as well as a deeper, gentler humor.

Broken Flowers

Directed by

Jim Jarmusch.

Focus Features. R.