Georges Lopez, the schoolteacher in Nicolas Philibert’s great documentary To Be and to Have, has a soft-bearded, ruminative face and vigilant eyes. He’s been instructing children in the Auvergne region in France for twenty years and now, in his mid-fifties, is ready to retire. The film chronicles his final year, and it’s one of the most emotionally gratifying movies about teaching ever made. It recalls the best films of Frederick Wiseman.

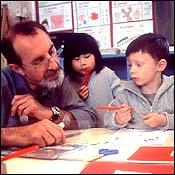

In the single-classroom arrangement, which is practiced less and less in France nowadays, children from kindergarten through primary school are taught in one big classroom by the same teacher; each age group occupies its own corner. Lopez moves deftly back and forth between them, adjusting his style to fit the children’s needs. He rarely tells students to just do something; instead, he gently questions them in Socratic fashion until they are able to discover their thoughts and feelings for themselves. When the children are distressed or misbehaving, he is careful to let them know his displeasure in ways they can understand. His patience is due, I think, to much more than a calm disposition. Lopez’s connection to children is based on the implicit understanding that their feelings are as valid and complex as any adult’s. And this is the principle that guides Philibert as well. He spent a great deal of time trying to find the right teacher for his film, and in Lopez he found more than a good subject. He found a soul mate.

Lopez is the apotheosis of all the great schoolteachers we wish we had (or were lucky to have had). It’s one thing to see movies like Dead Poets Society and Goodbye Mr. Chips; they carry a built-in nostalgia for a way of schooling—a way of life, really—that is no more. But To Be and to Have has a far greater emotional impact because it demonstrates without overreaching what an actual teacher can do to shape lives. Lopez doesn’t deny the harshness of his children’s problems. When a girl, who may be autistic, lets on that she is afraid of middle school, he tells her that she can still visit him—her new school isn’t far away—but he doesn’t gloss over her difficulties. When another student breaks down because of a parent’s illness, Lopez tells the boy that sickness is a part of life. He isn’t trying to be a father to these kids—not even when it’s clear they want him to be. He is gratified by their attentions and by what they give back to him. The son of a Spanish-immigrant farmhand and a French mother, he says he wanted to be a teacher even when he was a schoolkid, and it’s easy to believe him. Near the end, the children say good-bye one by one to Lopez, and those alert eyes of his mist up. The emotional honesty of this movie rescues it from sentimentality. To Be and to Have is about more than a dedicated teacher and his pupils; it’s about how difficult and exhilarating it is to grow into an adult.

The business of life lessons and growing up is given the Hollywood treatment in Secondhand Lions, written and directed by Tim McCanlies. Just about everything in this movie seems secondhand. Which may be the point. But familiarity this familiar breeds, if not contempt, then at least a big case of the blahs. Robert Duvall and Michael Caine play Hub and Garth McCann, brothers who were once rumored to be bank robbers but now spend their days grousing on their ranch in Central Texas and shooting at traveling salesmen from their rickety porch. Their 14-year-old grandnephew Walter (an alarmingly grown-up Haley Joel Osment) is dumped on their homestead by his errant mother (Kyra Sedgwick), who wants him to find out where the brothers’ mysterious cache of loot is hidden. But the boy isn’t interested in spying, and before long the old coots warm to him and teach him what it takes to be a man. Apparently, all it requires is a hefty appetite for homilies.

The film is mostly set in the early sixties, which McCanlies seems to equate with the thirties. A Dust Bowl–ish aura hangs over everything, and Walter has few interests for a boy of his era. McCanlies periodically intercuts re-creations of the brothers’ “Arabian Nights”-style tall tales—or are they?—but they serve only to point up how equally hokey the Texas scenes are. About the time Hub and Garth take delivery of a lion—which of course turns out to be decrepit—you may already have overdosed on cornball symbolism.

The only saving grace is that Caine and Duvall don’t overdo the southern-coot stuff. Caine does the smart thing and camouflages his flagging Texas accent by speaking softly and sparingly. Duvall, as usual, plays up his accent. My trusty movie encyclopedia tells me that Duvall was born in San Diego and went to college in Illinois, but somehow he’s become Hollywood’s resident cracker of choice. But like those of Meryl Streep at her best, Duvall’s performances aren’t only about the accent. His accents jump-start his characterizations in the same way that some actors are inspired by a bit of costuming or a fake nose.

These days, I admire John Sayles more for what he attempts than for what he accomplishes. He has managed to make a career out of personal projects of fine human and political interest. The only problem, oftentimes, is the films themselves, which tend to be earnest and overlong. His new film, Casa de los Babys, runs only 95 minutes—a veritable featurette for Sayles—but it seems overlong, too. Maybe that’s because there’s so much chatter. We’re plunked down in a South American hotel with six American women who are fulfilling the country’s residency requirement and enduring its red tape while waiting for the arrival of the babies they hope to adopt. The cast, which includes Maggie Gyllenhaal, Marcia Gay Harden, Daryl Hannah, Susan Lynch, Mary Steenburgen, Lili Taylor, and Rita Moreno, is first-rate, but each is given a single note to play. One scene stands out: a conversation between Lynch’s character and a hotel maid (Vanessa Martinez) in which they speak of their woes without understanding each other’s language—and yet on a deeper level, they understand everything.