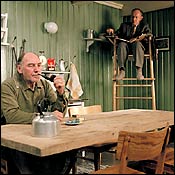

The premise of the Norwegian comedy Kitchen Stories, directed by Bent Hamer, is wonderfully oddball. In postwar Scandinavia, scientists obsessed with studying the kitchen routines of superefficient housewives have now moved on to single men—a far more ornery breed. Deployed to a remote Norwegian village and installed in high wooden chairs perched like aeries above the subjects’ kitchens, the researchers are forbidden to converse. At night, they sleep in green, ovoid trailers parked outside. Scruffy, passive-aggressive Isak (Joachim Calmeyer), a farmer who putters under the gaze of Folke (Tomas Norström), initially resents the intrusion, even though he has volunteered for the experiment. (He’s been promised a horse.) He eats most of his meals in his bedroom and, unbeknownst to Folke, drills a peephole into the kitchen so that the observer becomes the observed. Dressed immaculately in suit and tie, Folke endures Isak’s surliness for the sake of science, but it’s clear he’s not cut out for the job. He’s a bachelor himself, and as the movie goes along, his own eccentricities emerge. Inevitably, the two men begin interacting: In what passes for a moment of high emotion, Folke drops Isak some tobacco for his pipe.

It’s an apt coincidence that Norström looks like Alec Guinness, because Kitchen Stories has some of the same dry, finicky charm of Guinness’s Ealing comedies, especially The Man in the White Suit (which was also about the misadventures of science). The notion that men’s household habits are worthy of study, that they have a quantifiable predictability, is inherently funny. Isak may not look representative of the species—he’s on the outermost margins of domesticity—but in fact he’s the perfect specimen. The film is saying that, left to their own devices, all men would devolve into a morass of monastic grouches. Kitchen Stories is a prime piece of comic anthropology.

It might seem as though there is nothing new to be done with the crime thriller, but The Code (La Mentale), directed by Manuel Boursinhac and written by Bibi Naceri, provides a new twist. The Parisian suburban underworld it depicts is a blend of Gypsies, blacks, French-born North Africans, and Jews, and their clannishness is as integral to the movie as their turf wars and shakedowns. These criminals are united by their desire to work outside the law; greed and corruption are the great levelers.

Dris (Samuel Le Bihan), released from jail after four years, wants to go straight, but his cousin and best friend, Yanis (Samy Naceri, the screenwriter’s brother), wants to pull him back in for another job. This trope is familiar, but what lifts it out of the ordinary is Yanis’s almost feral desire to break Dris’s marriage apart. In the film’s most shocking scene—more shocking than any of its overtly violent ones—Yanis menaces Dris’s wife (Marie Guillard) while she is alone. This is more than intimidation for the sake of crime; Yanis, although he would abhor the idea, is in love with Dris.

So, it seems, is virtually everybody else. Le Bihan’s aura energizes the rest of the cast. He convinces not only as a thug but also as someone who desperately wants to reform. The reason so many people, including a ravenous Gypsy girlfriend (Clotilde Courau), want to drag him back into the game is that they sense his conversion would give the lie to their own lives. Dris is far from immune to their siren calls, but he has a moral core that breaks through his bravado: When Yanis, enraged at a gangster for a casual slight to his manhood, suddenly kills him, Dris is aghast. He asks Yanis, “Why do you take life away?” It’s a question not often asked in crime movies, but it should be.