On the commercial front of the civil war between red and blue America, there’s no stronghold farther behind enemy lines than Bentonville, Arkansas—home to Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. Union-bashing, Republican-backing, southern-fried to its core, Wal-Mart is the corporate face of Nonurban USA. And in Bentonville, it’s as pervasive and all-sustaining as the Walt Disney Company is in Disneyland. Down every street is another branch of Wal-Mart’s sprawling operation, from the 1.2-million-square-foot distribution center to the Wal-Mart museum housed inside founder Sam Walton’s original five-and-dime. In the center of town, across the road from Keith’s Auto Supply, squats Wal-Mart’s headquarters (known in local parlance as the “home office”). Made of dull red brick, just a single story high, the building is a converted warehouse. Its oceanic parking lot calls to mind the Meadowlands’.

One bright Monday morning not long ago, I found myself hiking across the lot, searching vainly for the lobby. I’d come to visit as the result of an unusual and irresistible invitation. Late last winter, Wal-Mart had seen its plan to open its first store in the five boroughs—in Rego Park, Queens—thwarted by a flurry of political opposition. In the months since then, its top executives had said nothing publicly about the controversy or their future ambitions for the city. But now, apparently, Wal-Mart’s CEO, Lee Scott, was ready to break the silence. His chief handler had called and offered me the chance to fly down for a chat.

Until recently, Wal-Mart was among the least chatty of American business titans. For years after its founding in 1962, its attitude to the press ranged from abject indifference to thinly veiled contempt. But in 2002, Wal-Mart sailed past ExxonMobil to become the world’s largest company. (Last year, its sales totaled a staggering $285 billion and its employees numbered 1.6 million.) Since then, it has become, as well, searingly controversial: an emblem of capricious corporate power, accused by its mainly liberal critics of paying poverty wages, granting meager benefits, discriminating against female workers, violating immigration laws, decimating mom-and-pop businesses … the litany goes on.

And so, with its image battered and its stock price stalled, Wal-Mart has lately, if reluctantly, joined the public conversation about its business practices. Speeches have been given. Ads run. A media day in Bentonville convened.

But as I discovered when I finally found my way to Lee Scott’s office, Wal-Mart’s new willingness to speak its mind doesn’t mean it’s changed its tune. Nor does it mean that its appetite for expansion is any less ravenous. Among the firm’s foes in the battle of Rego Park, the widespread assumption is that the wolf will very shortly be at the door again. And Scott confirmed that on this point, at least, his opponents are dead right.

“We’d still be a large, successful company without being in New York, but there are customers there who need to be served,” Scott declared soon after we sat down to talk. “I think New York will be good for us and we’ll be good for New York.” And make no mistake, he added emphatically, “We will be in New York.”

Wal-Mart’s determination to invade a city that’s already kicked it squarely in the teeth may strike casual observers as bloody-minded, masochistic, sinister, or all three. Mostly, in fact, it’s a logical response to a dilemma faced by any company that attains such vast proportions. With more than 3,500 stores in the United States alone, Wal-Mart is fast approaching saturation in the rural and exurban markets on which its business has been built. In order to grow at a rate that will keep its shareholders satisfied, the company has little choice but to launch a series of incursions into urban centers. As fervent as Scott is about New York, he speaks with equal ardor about Los Angeles and Chicago, both cities where Wal-Mart has big things in mind—and has encountered formidable resistance.

Yet, as Wal-Mart and its critics are well aware, the stakes in New York are greater. Not just because the market is so big and potentially lucrative. And not just because Wall Street is here. But because for both sides—each possessed of its own distinctive vanities and conceits—the outcome is freighted with so much symbolic weight in the current cultural climate. With some critical interpretation, Wal-Mart vs. New York is Bush vs. Kerry all over again.

Certainly, politics was front and center in the furor over Rego Park. It began in December, when a Wal-Mart real-estate manager, speaking at a shopping-center conference, revealed the company’s plans for its maiden foray into the city. In 2008, the manager said, Wal-Mart intended to open a 135,000-square-foot store in a mall being developed by Vornado Realty Trust on a site where Queens Boulevard meets the Long Island Expressway. As it happened, a reporter from Newsday was in the room, and the story hit the paper the next morning.

Virtually overnight, a noisy and adamant coalition sprang to life, intent on blocking Wal-Mart’s debut. Corner stores, green activists, neighborhood groups, and labor unions (especially the unions) threatened to lobby against Vornado’s land-use application. Soon enough, Democrats around the city, including mayoral candidates Gifford Miller and Anthony Weiner, clambered aboard the bandwagon. Even Mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose initial comments about Wal-Mart’s impending arrival were vaguely positive (“The public votes with their feet”), suddenly began to backtrack. As Pat Purcell, organizing director of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 1500, put it later, “What politician is going to be the one to let Wal-Mart in in an election year?”

Vornado rendered the question moot at the end of February. Reeling from the backlash and apparently fearful that it jeopardized the entire project—which included an array of other stores and a pair of apartment towers—the developer informed the City Council’s Land Use Committee that Wal-Mart was no longer in the cards for Rego Park.

For the anti–Wal-Mart coalition, the victory was sweet but fleeting. Within days came word that the company was eyeing two sites on Staten Island. Since then, the coalition has been marshaling its forces, aggressively pushing the City Council to pass measures designed, in effect, to bar Wal-Mart from New York for good, and denouncing the retailer in terms as vivid as they are cartoonish. “Wal-Mart is like the Death Star,” says Richard Lipsky, the head of the Neighborhood Retail Alliance. “You can wipe them out, but they’ll be back.”

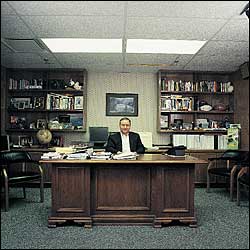

Lee Scott would never be Central Casting’s choice to play the role of Darth Vader. A 56-year-old native of Joplin, Missouri, who grew up in Baxter Springs, Kansas (population 4,602), he has short brown hair and an affect that’s a mash-up of Andy Griffith and Mr. Rogers. On the day we meet, he wears wool pants, a leather jacket, and a yellow polo shirt buttoned up to his Adam’s apple. His office décor screams mid-seventies suburban rumpus room: There’s a fish tank, wood paneling, low-pile carpet, and a view of the parking lot. A stack of books is piled high on his desk, with Jared Diamond’s Collapse on top, just above The Wal-Mart Way.

Scott has spent 26 years at Wal-Mart, rising through the ranks to become its third CEO. The first, Sam Walton, earned his legendary status by helping invent the concept of big-box discount retailing. The second, David Glass, turned Wal-Mart into a paragon of high-tech efficiency. Scott, who took the reins in January 2000, tells me that he sees himself as a “transitional” figure in the company’s history. It’s fallen to him to manage Wal-Mart’s shift from provincial rising star to global behemoth—and magnet for controversy. In his willingness to open up the company (a bit) and answer its critics (however haltingly), he seems intent on styling himself as Wal-Mart’s Gorbachev.

Scott’s idea of glasnost begins with an acknowledgment that all those critics aren’t congenitally “evil.” Some, Scott says, are sincerely trying to make the company better, while others are pining for a sepia-toned America that is inexorably slipping away. “There are people who care about sprawl and envision a life that’s more like where I grew up,” he says. “A life where people park and walk down Main Street and shop store to store to store. I actually have respect for those people. I think their intentions are good. But they have a view of life which I don’t think is coming back. And I don’t think society should protect that view of life.”

What Scott can’t abide is a different brand of critic—the kind he sees as the source of Wal-Mart’s troubles in New York. “We don’t like it when people are calling in their chits and are willing to vote against what we see as customers who need us,” he says. “And while you don’t in any way want to be dismissive of people’s arguments, it’s hard for us to look at New York and have someone say they’re against big boxes. It would appear that it’s somewhat late for that.

“So let’s talk about what the real issues are and stop masking them with ‘our interest is only the good of mankind’ bull crud,” he adds. “It doesn’t have anything to do with wages. It doesn’t have anything to do with the box. It doesn’t have anything to do with anything other than fear: ‘How are we going to compete? How are we going to protect the status quo?’ ”

Scott is referring here mainly to unions—another thing he can’t abide. To his way of thinking, it’s not organized labor but Wal-Mart, with its “everyday low prices,” that’s the true friend of the workingman. “People here in Arkansas think of New York as all Wall Street traders making big money and living big lives,” he says. “They miss the whole issue that New York is made up of millions of working people who live paycheck to paycheck, and that saving 10 percent on their daily needs allows them to go to the movies, to go out to eat, to do things differently than they would otherwise have done. When you take an area like New York City and decide you’re only going to allow so much competition, that you’re going to set a limit and not participate in the things that make this country great—well, by golly, I think that’s a huge decision for those working people.”

Scott maintains this populist posture throughout our conversation to the point of self-parody, waxing lyrical about how the arrival of Wal-Mart to various inner cities has brought hope and opportunity. To illustrate, Scott begins to tell a tale about Baldwin Hills, California—when his handler, Mona Williams, a soothing but steely PR veteran with a lilting southern accent, leans forward and interjects.

“Baldwin Hills is on the edge of Watts, just to give you a picture,” she says.

“You remember the movie Training Day?” Scott asks. “It was shot a mile and a half from that store.”

“Scary, scary movie,” Williams mutters, aghast at the memory. “That movie scared me to death.”

“Well,” Scott says, “I went into a store in Los Angeles and met this young African-American lady, asked her when she started at Wal-Mart. She said she started two years ago, when we opened in Baldwin Hills, as an hourly associate, not having any idea of what her future held because jobs were so tough. And in two years, she’s already been promoted to the assistant-manager program and her life has changed.”

Scott leans back, slaps his leg, and uncorks a satisfied smile.

“You don’t make those stories up,” he says. “And there’s thousands of stories like that.”

There are indeed lots of stories about Wal-Mart and its workers, few of them so luminous. (And there will be even more come this fall, when Robert Greenwald, the guerrilla documentarian of Outfoxed fame, releases his next film, Wal-Mart: The High Price of Low Cost.) Though the company is America’s largest employer, it is hardly the most generous, paying on average just $9.68 an hour, providing health insurance to fewer than half its workers, and requiring those who do receive coverage to cough up a third of the cost. I ask Scott about an observation made by both Times columnist Tom Friedman and former Labor secretary Robert Reich: that while Wal-Mart’s business savvy and low prices may cause us to admire it as consumers, its miserliness inspires scorn from us as citizens and workers.

“The argument’s baloney,” Scott snaps, displaying a rare flash of irritation. “Somebody asked me the question, ‘Why don’t you pay everyone a minimum of $12 an hour?’ And my question is, ‘Why $12? Why not $20?’ The next question is, of course, ‘Well, why not $20?’ But I think there are countries that have tried that and it didn’t work well. I mean, look at Europe!”

Scott then notes that Wal-Mart pays nearly double the federal minimum wage of $5.15 an hour. And that its benefits compare favorably with those of its retailing rivals. All in all, Scott proclaims, “we consider ourselves progressive.”

I suggest that Scott’s definition of the term is one that most New Yorkers—nay, most of blue America—would fail to recognize. I ask whether, given this, he really believes that Wal-Mart is a good cultural fit with the city.

“Is there an inherent bias against people from the South among the elite in New York? I can’t imagine that!” Scott says with a laugh. “Though I did grow up watching Green Acres.” He continues, “I get a lot of letters from people in New York, and some are not particularly pleasant. But I also get a lot that say they agree with the mayor that the consumer ought to be the one who makes the final choice. The people I deal with in New York, like Paul Charron, who runs Liz Claiborne—of course, Paul’s from Kentucky originally—as they get acquainted with Wal-Mart, they find a great deal to respect. And as people get to know us, this whole issue of red state–blue state, or urban and nonurban, most of that goes away.”

Maybe, maybe not—but we’ll never know when it comes to New York unless Wal-Mart manages to hurdle the initial wall of opposition.“These things move in cycles,” Scott concludes, striking a note of Realpolitik. “The power moves. The influence moves. The economy moves. And when things are booming, maybe it’s easier to say no. But when things are tougher, and people are driving to Secaucus to shop at Wal-Mart, and sales-tax dollars are leaving the community, common sense will prevail.”

Before I flew down to Bentonville—one sign of Wal-Mart’s gravitational pull is that you can get there nonstop from La Guardia—Mona Williams had expressed some frustration with the press’s treatment of the company. (Scott had made his own feelings known a few months before, when he told the Associated Press that he felt like he was being “nibbled to death by guppies.”) Displaying a certain unfamiliarity with New York media dynamics, Williams seemed most worried not about the tabloids or the Times but about a scathing piece in December in the New York Review of Books. (“NYRB seems to be a ‘thinking person’s’ publication,” she fretted to me in one e-mail.) By inviting me to Bentonville, Williams said, the company’s aim was “to frame this debate in a smarter direction.”

Wal-Mart’s critics will no doubt regard Scott’s arguments not as smart but as self-serving. Predictably, he glosses over a mountain of evidence that suggests the firm is a model employer in the way that Arthur Andersen was a model accounting firm. Wal-Mart is fighting scores of “wage and hour” lawsuits involving managers said to have either tolerated or compelled off-the-clock work. (In Bentonville, Williams stressed that Wal-Mart’s new approach to such incidents is to fire the managers immediately—but then Scott chimed in, “I do worry about all the firings, though.”) Last year, Wal-Mart paid a record $11 million to settle an investigation by U.S. Immigration officials into its hiring of undocumented workers. The firm is currently facing the largest class-action suit ever certified: a sex-discrimination case that could include the claims of 1.6 million current and former female Wal-Mart employees.

“Why $12 an hour? Why not $20? There are countries that have tried that, and it didn’t work well. I mean, Look at Europe!”

This bill of lading is troubling, to be sure, but it’s only one source, and perhaps the least significant, of New York’s hostility to Wal-Mart. More powerful and deeply rooted are the city’s singular self-image, its collective neuroses and prejudices (which are, after all, as extravagant and fully developed as those of any Woody Allen character), and an array of entrenched economic interests that are, just as Scott asserted, profoundly threatened by the impending Wal-Mart invasion.

Dominating the last category, of course, are the city’s unions—in particular the UFCW. As Wal-Mart has moved away from selling only dry goods and into the supermarket game, the grocery-workers union has become, across the country, the company’s fiercest opponent. In New York, the UFCW remains one of labor’s most robust divisions; its role in the Rego Park dustup was, by all accounts, pivotal. It’s also one reason, say many economists, that food prices in the city are so much higher than they ought to be. In any event, if you’ve ever wondered why Target has set up shop here with very little hassle—despite being nonunion and paying its workers as poorly as Wal-Mart does—the reason is that Target doesn’t compete with grocery stores (yet) and thus imperil the UFCW.

Reinforcing the clout of the unions is a more evanescent but no less potent force: Manhattanite snobbery. In the outer boroughs, where shopping outposts are scarce, badly stocked, and painfully overpriced, big boxes have been met with open arms by consumers—and there’s no reason to think that Wal-Mart wouldn’t be, too. (For what it’s worth, a Wal-Mart–commissioned poll by the Marino Organization found that 62 percent of New Yorkers favor the company’s entering the city.) In Manhattan, though, that shoppers’ Xanadu, the need for Wal-Mart is minimal and the desire for it close to zero. The objections are partly political, but even more so, they’re aesthetic: Wal-Mart is ugly, tacky, down-market. (The very idea of shopping at a store because it’s cheap—ick.) Never mind that precious few Manhattanites have ever encountered a Wal-Mart. Their contemptuousness colors the debate anyway, especially in the press.

Standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the snobs at the barricades are the nostalgists for Old New York. Anti–Wal-Mart leader Richard Lipsky writes on the Neighborhood Retail Alliance’s blog that a key element of the campaign against the company is a “conservative populist” appeal: that Wal-Mart will destroy the commercial fabric of the city. Propounding what he calls the “neighborhood character” argument, Lipsky holds forth: “For conservative Wal-Mart supporters who have never lived in an urban atmosphere, it is difficult to comprehend the importance of walk-to-shop commercial strips, mom-and-pop shops, and the general aversion to suburban-style developments.”

Having heard Lipsky deploy this argument during the Rego Park imbroglio, and curious about the neighborhood character Wal-Mart would have disrupted, I drove out and had a look around the site of the incipient Vornado development. Within a few blocks of where Wal-Mart’s first New York City store would have stood, I saw a CVS, a Payless, a Pizza Hut, a Baskin-Robbins, a Dunkin’ Donuts, a Subway, and a Sizzler. Also a Bed Bath & Beyond, an Old Navy, a Circuit City, a Sears, and a Marshalls. (Corner stores were there as well, but they were few and far between.)

The point, to be clear, isn’t that neighborhood character doesn’t matter. It’s that when it comes to the matter of national chains taking over the New York retail landscape, the horse escaped the barn long ago—and shutting out Wal-Mart won’t do a damn thing to drag it back in again.

As we wait for the inevitable next installment of Wal Mart vs. New York, it’s helpful to recall that the city has seen a movie quite like this before.

In 1974, McDonald’s, having neglected urban markets as it pioneered the American fast-food business, announced its intention to open a restaurant at 66th and Lexington. As John F. Love recounts in his history McDonald’s: Behind the Arches, the outcry was swift and severe. Picket lines formed in front of the construction site. Opponents stormed a community-board hearing to rail against the project. Wall Street analysts downgraded the company’s stock, citing the stiff challenges it faced in urban markets. In a cover story in the Times Magazine, food editor Mimi Sheraton wrote a scalding piece, “The Burger That’s Eating New York,” in which she not only trashed the Big Mac, but also attacked founder Ray Kroc for contributing cash to Richard Nixon’s campaign. According to PR guru Howard Rubenstein, who spun for McDonald’s amid the turmoil, “It was one of the most brutal confrontations any community has ever organized against a business.”

Sound familiar?

For the city, the McDonald’s precedent is at once reassuring and alarming. On the one hand, there now some 250 sets of Golden Arches scattered around the five boroughs—and as far as one can tell, their proliferation has caused no appreciable degradation to New York’s quality of life or the quality of its cuisine. On the other hand, it’s hard to argue that having a McDonald’s every few blocks represents some Edenic ideal. Or that the consumption of roughly a zillion Quarter Pounders has done the city (apart from its cardiologists) any favors.

For Wal-Mart, by contrast, the McDonald’s story imparts essential lessons. In order to end the contretemps at 66th and Lexington, the company was forced to negotiate a truce that entailed the abandonment of the project.

But that wasn’t all it did. “After that experience,” Love writes, “McDonald’s developed a policy to assess a community’s political environment carefully before building a new unit and respond to any resistance early—before positions on either side became public and intractable.”

For Wal-Mart to break through in New York, following a similar path will be necessary, but it may not be sufficient. We live today in a different world, more amped-up and polarized, and Wal-Mart is a much larger and more important company than McDonald’s has ever been. All of which means that Wal-Mart is a riper target.

Lee Scott knows that Wal-Mart must become more politically adept, more sensitive to local fears. But his belief in Wal-Mart’s manifest destiny is sturdy—and not a little unnerving. “There’s no reason we shouldn’t be at least twice as big in the U.S. as we are today,” he told me. “And whether you in New York get a store this year or next year or five years from now, if we do the things we should do, then ultimately we will prevail.”

How can Scott be so sure?

“Well,” he says with a little laugh, “we’re going to be around a long time.”