The first thing you might notice about Jeffrey Greenberg is how modest and self-effacing he can be, particularly for a man who’s held a couple of the most important jobs in the insurance industry. “Jeff was very clever in his way, playful,” says Mark Reagan, a fellow insurance executive who once worked for Greenberg. “You’d walk out of a tough meeting, and Jeff might say, ‘That wasn’t as much fun as I hoped.’ ” As a young man, Greenberg was the type who, despite his family’s wealth, insisted on pumping gas and scrubbing boats to pay off a new car. Even when he went on to earn $22 million last year, Greenberg lived with his second wife and four kids in a relatively unassuming apartment on Park Avenue. Before he became CEO of Marsh & McLennan, a job he held for five years before being forced to resign late last month, Greenberg had a reputation for stepping in to claim responsibility when higher-ups lashed out at his subordinates. There is something almost cartoonishly all-American about him. At six feet tall, Greenberg has the build of a natural athlete. He was, in fact, a standout sprinter, football player, and skier at Choate. As of last month, the 53-year-old Greenberg remained one of the tougher tennis matchups on the executive circuit.

Greenberg is also a textbook incarnation of corporate establishmentarianism. He is a trustee at Brown, his alma mater; at Brookings, the granddaddy of Washington think tanks; and at New York’s elite Spence School, which his eldest daughter attended. Greenberg would be perfectly at home in the halls of the Council on Foreign Relations or at a meeting of the Trilateral Commission. (He’s a member of both institutions.) His family spends weekends at their house in northern Connecticut.

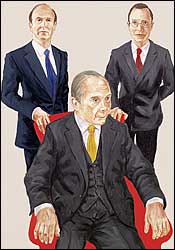

But for all Jeff Greenberg’s obvious successes, he’d never escaped the shadow of his larger-than-life family. His father, Maurice R. “Hank” Greenberg, the CEO and chairman of AIG, is quite possibly the most famous man in the history of the insurance business. Hank almost single-handedly built the company into a global financial-services powerhouse over the past 37 years. At least since adolescence, Jeff has been dogged by the sense that nothing he could accomplish would amount to more than a footnote alongside the achievements of his father.

For his part, Hank, whose management style former employees have compared to George Patton’s, did his best to remind Jeff of this fact during the seventeen-year period he worked for his father at AIG. “Do I think he was harsher because [Jeff] was his son? I think the answer is yes,” says one former AIG executive. In one notorious incident, Hank blew up at Jeff over a personnel problem in a roomful of colleagues. “You either fix your management problem or I’ll fix mine!” the father reportedly bellowed. “I think it was a case of two people from the same gene pool with extraordinarily high success drives,” says this executive. “And there’s only so much oxygen in any given room.”

Jeff Greenberg’s white-collar sensibility didn’t mean he refused to play hardball like his father, Hank, or his brother Evan. It’s just that Jeff wasn’t as good at it.

To further complicate the matter, Jeff was not the only Greenberg son high up in the AIG hierarchy. Toward the end of Jeff’s time at AIG, his younger brother Evan was head of the company’s international operations—and probably the only person who’d risen faster at AIG than Jeff. The brothers had been lifelong rivals. Jeff had always been the good son—successful at school, successful at work, but never quite successful enough to impress Hank. Evan, by contrast, had a knack for screwing up, though he’d earned a special place in Hank’s heart over the years for having the guts to defy him. When Evan began to prove himself Jeff’s equal in the family business, it was more than Jeff could handle. In June 1995, the combination of this fraternal competition and his father’s suffocating management style led Jeff to resign—and walk away from what many observers expected would be his eventual takeover of the company.

Jeff Greenberg landed at the giant insurance brokerage Marsh & McLennan, where within four years he rose to CEO. It was a triumph, confirmation that he was ultimately his own man. Then two weeks ago, with the firm under fire from New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer, Jeff Greenberg’s career came crashing down. Spitzer is accusing Marsh & McLennan of rigging what were supposed to be competitive bids and collecting kickbacks from insurance companies in exchange for lucrative business. Watching Jeff tender his resignation, you could be forgiven for concluding he was just another greedy CEO getting his comeuppance. But in fact, it’s impossible to judge the story of Jeff Greenberg’s rise and fall without understanding the family dynamics that drove him throughout his career.

When AIG went public in 1969, Hank Greenberg became a very wealthy man, something that would have been difficult to imagine when he set out on his professional career. Hank had come home from the second of two tours of duty in the Army (the first saw him storm Omaha Beach as a Ranger, the second put him in Korea as a military lawyer) in desperate need of a job to support his wife and newborn son Jeff. He went looking for one up and down William Street, then the center of the New York City insurance industry. Legend has it Hank eventually talked his way into an entry-level underwriting position at Continental Casualty after treating the boss of a dismissive personnel employee to an animated lecture on deportment.

That was 1952. By 1959, Hank had moved to Chicago and become the youngest vice-president ever at Continental, overseeing the company’s accident- and health-insurance operations. Then, in 1960, a mentor of Greenberg’s recommended Hank for a job at American International Companies. By 1962, Hank had taken over the company’s domestic operations, American Home, which at that point could barely be considered “third-rate,” according to David Schiff, the dean of insurance-industry analysts. Hank transformed it into a steady source of profits. Some five years later, buoyed by this success, he took over as head of the entire company, which he incorporated as AIG.

Though Hank ran a company with hundreds of millions in annual revenue, the Greenberg household in the early seventies hardly gave the impression of abundant wealth. The Greenbergs lived in a fairly modest three-bedroom apartment on Park Avenue, with Jeff, Evan, and younger brother Scott sharing a bedroom when they were home from boarding school or college. The kids were “not arrogant for the amount of money they had, less arrogant than most,” says Mark Abouzeid, the son of an AIG executive who grew up around the Greenbergs. In fact, Hank was determined not to flaunt his good fortune. Friends were struck by how proud the family was that its modest country home in Brewster, New York, looked even smaller from the roadside.

Visitors to the Greenberg residence at the time recall Hank as an almost compulsively disciplined and health-conscious man. The family routinely ate tofu, long before it was fashionable; Hank rode his exercise bike every morning while watching the Today show. Even Thanksgivings were hardly feasts. “I was always on a diet, but everybody would watch what everybody ate,” says Nikki Finke, a Hollywood columnist who was Jeff’s first wife and who first met the family when Evan and Jeff were teenagers. “It wasn’t like, ‘Loosen your belt.’ For Hank and [wife] Corinne, it was more to see how little could you eat.”

In Hank’s view, the family was an inviolable social unit. The Greenbergs always vacationed together, whether at the AIG-owned resort in Stowe, Vermont, or at the Ocean Reef Club in Key Largo, Florida, where Hank owned a modest-size boat. Weekend activities consisted of games of tennis among family members or family ski outings, in which the atmosphere was invariably tense. “If you played tennis, you played tennis,” recalls Abouzeid. “I didn’t really enjoy it; it was too competitive. They’re all very serious.”

AIG, too, was an extension of the family. Company Christmas parties were family affairs, and Hank made a point of getting to know the names of all the executives’ children, who were strongly encouraged to follow their fathers into AIG management. “Hank was at my sister’s wedding, and I remember him coming up and saying, ‘So, when are you starting with us?’ ” says Abouzeid. “I looked at him straight in the eyes and said, ‘Sir, that’s not going to happen.’ He just kind of smiled.” And, of course, Hank envisioned his own sons sitting at the top of the organizational chart. “The whole thing from their father while they were growing up was, ‘You’re going to take over this some day,’ ” says Finke.

Since at least their teenage years, Jeff and Evan found themselves playing out what seemed like biblically assigned roles: Jeff was the dutiful son, determined to please his demanding father. Jeff parroted his father’s conservative political views and was desperate to impress the older man with his studied knowledge of foreign affairs. Invariably, Hank would be dismissive. “His father would treat him like, ‘You don’t know anything. Don’t even try to compete with my knowledge,’ ” says Finke. “No matter what Jeff did, according to his father he couldn’t hold a candle to anything Hank had done.” Finke remembers Jeff being paralyzed with fear that his father might pull him out of school after a disappointing first semester at Brown.

Evan, by contrast, was the rebel—as if, after watching Jeff, he concluded that there was little he could do to please Hank and therefore wouldn’t try. Evan acted up in school, showed up haphazardly for family events, dated older women, and generally drove his parents to distraction. “There was never a meal where they didn’t wring their hands about Evan—especially when he wasn’t there,” says Finke. And Jeff, who resented the amount of attention Evan got for doing nothing but screw up, unfailingly took his parents’ side. But according to Finke, for all of Hank’s ranting about Evan, there was a part of the old man that seemed to admire the kid’s guts. “Hank was not used to anybody defying him,” says Finke. “Evan did. In a bizarre way, Hank had a grudging respect for Evan.”

After college, Jeff headed to Georgetown law school, and then to a management job at Marsh & McLennan. But college wasn’t in the cards for Evan. He left home on a hitchhiking tour of the country, stopping from time to time to make a few bucks as a cook or a bartender. Evan eventually surfaced in Denver, where Hank quietly arranged for an AIG associate named Carl Barton to offer him a job. Evan accepted when Barton promised not to out him to his new colleagues as Hank Greenberg’s son.

Jeff moved from Marsh & McLennan to AIG’s London office in 1978, after constant nagging from his father (“When are you going to stop this nonsense and come to work for me?” Hank would ask), by which point Evan was back in New York working at the company’s headquarters. Jeff was on the management track, while Evan toiled away at lower-level jobs. But therewas a connection developing between Evan and Hank, which stemmed partly from Evan’s physical proximity to his father and partly from Evan’s surprising knack for the insurance business.

Jeff, of course, was highly dismissive of his brother. When Evan’s name came up in conversation, Jeff would take a kind of “Oh, yeah, my brother the insurance expert” tone. But Jeff’s inability to distinguish himself in his father’s eyes, combined with the attention lavished on his younger brother, created a constant need for approval, which he sought in other places. At Brown, Jeff joined a nonexclusive fraternity, where he was looked up to, and when he lived in London, he hung out with a circle of “hooray Henrys”—well-bred underachievers who’d landed jobs through family connections.

There was another side to Jeff: He had a weakness for certain status objects. He drove an Alfa Romeo (that was the car he’d worked menial jobs to save for), his wardrobe was Paul Stuart, his watches were always Rolex. Socially, too, there were strains of self-loathing. Finke recalls that Jeff mentioned encountering mild anti-Semitism at Choate in the sixties. She believes one of the things that attracted him to her was her “Waspy Jew” appearance and private-school pedigree. When she came out as a debutante, Jeff insisted on being her escort.

These hang-ups may have even influenced Jeff’s choice of career. In the immediate postwar era, and as late as the sixties, the prestigious investment banks and law firms were still relatively closed to white ethnics. Talented, ambitious Jews like Hank Greenberg, who’d grown up working-class and had attended no-name schools, found the insurance industry somewhat more welcoming. There was more yelling, less formality. In beginning his career at Marsh & McLennan—which, as a brokerage, tended to be more white-collar—Jeff would have been able to break with his father not only professionally but also temperamentally and sociologically.

Several months ago, long before Eliot Spitzer unveiled his case against Marsh & McLennan, I went to the eighteenth floor of AIG’s Pine Street headquarters to interview Hank. The sitting room outside Hank’s office is heavy on wood trim and Chinese paraphernalia—vases, silks, photographs of Hank with Chinese leaders. I’m seated on a plush, reddish-orange couch, which I can’t help but feel is designed to swallow me up, while Hank fields my questions.

When Hank makes his way out of his office some ten minutes later, he doesn’t seem especially intimidating. He stands about five foot seven, lean, tanned, amazingly well-preserved—more like a man in his mid-sixties than his late seventies. He is jacketless and wearing a plain powder-blue shirt and gray slacks.

To break the ice, I ask a long (and, truth be told, rambling) question about his management style. Pretty soon I have an inkling of the survivors’ bond that must exist among the thousands of AIG executives who’ve worked for Hank over the years:

“Have you ever managed anything?” Hank snaps.

“Um, no.”

“What makes you think you have the right to question how I run this company?”

“I don’t think I have the right—”

“I don’t think so either. We have a capitalization of about $180 billion … Let me explain a couple of things to you. Because you are obviously not a student of management … ”

It occurs to me at this point that Hank looks and sounds a lot like Ben Gazzara.

Current and former AIG employees frequently refer to Hank as a genius, and the reason they say this is because of his extraordinary foresight. When he took over as CEO in the late sixties, Hank realized that the insurance industry would allow him to accumulate a series of advantages—all of them perfectly fair and legal—that would make AIG lots and lots of money. Or, to put it differently, Hank realized that the system could be gamed.

As late as the seventies, AIG didn’t have the kind of capital it would have needed to undertake the rapid expansion Hank craved. So he began aggressively selling policies—known as “writing business” in the insurance vernacular—and then passing much of the risk off to reinsurers, which act as insurance companies to insurance companies. AIG would, for example, write a policy that obligated it to cover up to $100 million in property damage, and then turn around and purchase its own insurance policy to cover $70 or $80 million of that amount.

This accomplished two things: First, it allowed AIG to establish itself as the kind of insurer that would go into lines of business so risky no one else wanted to touch them—insuring against things like sexual-harassment suits and kidnappings. (“All you read about are the people who are kidnapped,” Hank once famously quipped. “There are an awful lot of people who aren’t kidnapped who buy insurance.”) In these risky areas, Hank enjoyed near-monopoly pricing power, which allowed him to charge high premiums. Second, since he was buying so much reinsurance, Hank was able to negotiate incredibly favorable terms with reinsurers. Hank had become so proficient at this that in 1979 one executive at Aetna complained to Institutional Investor magazine that “we’re in the primary insurance business, the business of assuming risk. Greenberg is in the money business.”

Hank accumulated advantages in other ways, too. He built up a brutally efficient claims division—the part of an insurance company that determines whether the company will pay up on a policy—which kept the number of claims paid out to an absolute minimum. In one famous episode, an AIG subsidiary (along with a handful of other companies) insured the producers of the Broadway musical Victor/Victoria against the event that the show’s star, Julie Andrews, would be unable to perform because of illness. According to the Wall Street Journal, the policy cost about $150,000 and promised up to $2 million for missed performances, and $8.5 million if Andrews had to drop out of the show altogether. But when Andrews missed a series of shows, costing the producers more than $1.5 million at the box office, the AIG-led consortium refused to pay, insisting that Andrews had provided two false answers in the health questionnaire she filled out when purchasing the policy.

Of course, as in the Julie Andrews case, many customers challenged AIG’s judgments in court. To deal with this, AIG has historically retained many of the major corporate-law firms in the country. Not only does this give the company the wherewithal to bog down claims in legal wars of attrition. It has the added effect of monopolizing legal talent that might otherwise represent AIG customers. “AIG probably controls more lawyers than anyone else,” says Lehman Brothers analyst Chris Winans, a longtime student of AIG. “I’m serious. They’re invested in law firms, they have contracts with law firms. It gives them access to the best lawyering for the least amount of money.”

“Not onlywas Evannot upsetthat Jeff had leftAIG, he wastriumphantabout it. Hemade somecommentlike, ‘It’sgoing tomake familydinners a littleawkward.’ ”

Probably the best way to think of Hank is part casino owner, part poker shark. Like a casino owner, he has a knack for fixing the odds in his favor, and, if that doesn’t work, for refusing to let the customer walk away with his cash. Like a poker player, he bets big on good hands and quickly folds on bad ones.

The insurance industry is littered with executives who came up through the ranks at AIG—with Hank’s gambler ethos beaten into them—and then left to run their own companies, which they proceeded to run into the ground. In the past several years alone, onetime brand names like Kemper, Reliance, and Phico have all flamed out with former AIG officials at the helm, usually because they couldn’t resist the temptation to steal market share from their former employer. Professional poker players tend to use the term “dead money” to describe the amateurs who enter tournaments with big buy-ins and then promptly hemorrhage their chips. From Hank’s perspective, most of the scores of executives who’ve left AIG over the years to run other companies have amounted to little more than dead money.

To varying degrees, both Jeff and Evan Greenberg inherited Hank’s savvy, his brashness, and his bluster. But, outwardly at least, Jeff’s Ivy League bearing stood in contrast to his father’s and brother’s rougher edges. “Evan could be funny, but it was more straightforward,” says Mark Reagan. “Jeff was a little drier.”

For subordinates beleaguered by the old man’s intimidation tactics, Jeff’s relative calm was a welcome relief. “Jeff was in a category by himself. I thought the world of him then. I think the world of him now,” says one former AIG executive who reported to him. Evan, by contrast, seemed to have inherited Hank’s white-hot temper, lashing out at subordinates with warnings like “If you can’t fix this, I may need to clean house.” Underlings accustomed to this kind of abuse from Hank chafed when it came from Evan. “Greenberg Sr. entered the company when it was very small and went on to develop it into a hugely successful company,” says Tom Kaiser, who reported to Evan while at AIG. “If you haven’t gone through those years, and if you’re going to take the same level of authority, you’re doing it as someone else.”

Still, even critics concede that Evan shared many of Hank’s raw instincts for the business, some of which the more deliberative Jeff seemed to lack. Former colleagues recall Evan as the driving force behind AIG’s lucrative investments in the Internet and its e-business platform in the late nineties. “Evan sizes things up quickly, has a good eye for opportunity,” says Kaiser. “Jeff has to study it more.”

Jeff’s white-collar sensibility didn’t mean he refused to play hardball like Hank or Evan. It’s just that Jeff wasn’t as good at it. In 1992, for example, Jeff drafted a memo, dated the day Hurricane Andrew pounded South Florida, imploring AIG executives to treat the disaster as “an opportunity to get price increases now.” The memo quickly ended up in the hands of reporters, prompting multiple investigations and angry denunciations from the likes of Ralph Nader. The problem wasn’t so much the logic of the memo—which Hank fully endorsed. It’s that Jeff made the mistake of putting to paper a directive best issued more discreetly. The incident prompted some amount of “ranting and raving” from Hank, according to one former AIG executive.

Jeff resigned in 1995, after two things happened in rapid succession. First, Hank promoted Evan to the rank of executive vice-president, putting him on equal footing with his brother for the first time in their seventeen years together at AIG, a move that reportedly blindsided Jeff. Then, in late spring, Hank convened a dinner at the ‘21’ Club with executives of Jeff’s domestic-brokerage unit. Hank had traditionally scheduled off-site dinners to announce good news, like promotions, so most of the executives were looking forward to the evening. But when they arrived, they found Hank in a foul mood. “It was a general ass-kicking,” recalls Jeff’s de facto No. 2 at AIG, Bill Smith. “Jeff got in the middle of it, and Hank beat the hell out of him.” Several days later, according to Smith, Jeff told his subordinates he’d had enough, and tendered his resignation.

Jeff explained his departure as a chance to set off on his own—something that clearly rang true in light of the ‘21’ Club fiasco. “You know, after that, their relationship could not bounce back from that incident,” says a former AIG executive. “It obviously had been building for some time.” Hank, for his part, released a statement saying he was “personally saddened” by the departure, though he has never been one to let personal feelings get in the way of running AIG. Board members whom Hank talked to immediately following the resignation recall no discernible emotion in his voice.

Many within the company have speculated that Jeff was irked by Evan’s rapid ascent through the AIG ranks. Finke, whose marriage with Jeff had long since ended, remembers calling to congratulate him on having the gumption to walk away from his father. When Jeff returned the call, they began talking about the brothers’ relationship, and Jeff expressed disbelief about Evan’s rise to his own level within the company. “To the world, they were trying to present a united front, that it had nothing to do with Evan,” says Finke. “But I got the distinct impression—of course it had something to do with Evan.” Likewise, Finke recalls a conversation she had with Evan a year and a half later, in which she jokingly asked, “So, Jeff was scared of you, huh?” It became clear from the banter that followed that Evan was relishing his brother’s change of fortune. “Not only was he not upset that Jeff had left the company, he was triumphant about it. He made some comment like, ‘It’s going to make family dinners a little awkward.’ ”

Evan eventually left AIG, too, one of the many executives who defected to ACE, a big Bermuda-based firm. These defections gnawed at Hank, according to one insurance analyst who’s followed AIG for years. Says the analyst, “I know that [Hank] Greenberg would—nothing would make him happier than to see ACE go down the tubes.”

After leaving AIG, Jeff became a “hot commodity” in the insurance industry, as one Marsh & McLennan executive put it to the Wall Street Journal. His marketability was partly a function of the Greenberg name, which, thanks to Hank, had achieved a mythical status in the insurance industry. And it was partly a result of Jeff’s strong reputation within AIG, a company thought to possess the most elite managerial talent in the industry. Jeff joined Marsh & McLennan as a partner in a subsidiary called MMC Capital, a private-equity group focused on the insurance industry, in October 1995. He wound up on the company’s fast track, becoming CEO of MMC Capital the following year, then winning a seat on the Marsh & McLennan board two months later. In 1999, largely on the strength of his impressive performance at MMC Capital, where he’d made a name for himself presiding over high returns on investments in insurance companies and real estate at the unit’s Trident Funds, the Marsh & McLennan board named Jeff CEO and designated him the company’s future chairman.

By this point, many of the improprieties Spitzer alleges in his complaint had long since been under way. “My involvement with [Marsh & McLennan] was fifteen years ago. It was going on then. And it was going on long before I got there,” says one former Marsh & McLennan executive. “I think that Marsh and its operating companies operate in industries that have substantial corruption. But they’re a leader in it.” According to this executive, the business model at Marsh & McLennan has for decades involved using the company’s leverage in the marketplace to generate profits or win business it probably couldn’t have won on the merits. To take one example, the Marsh & McLennan–owned mutual fund called Putnam is currently under investigation for paying companies to include it in employee 401(k) plans. “Putnam paid financial intermediaries to get them in the door,” the executive continues. “Their performance in relation to cost made it obvious they were never hired on the merits. Look at their investment return, cost structure. These funds were mediocre performers at best.”

If Spitzer’s most recent allegations are accurate, then a similar logic applied to insurance brokering, Marsh & McLennan’s core business. Over the years, Marsh & McLennan is alleged to have generated a substantial portion of its profits from what are known as contingency agreements, in which insurance companies offered Marsh & McLennan kickbacks for sending business their way. Marsh & McLennan would send business to the insurance company offering the most generous kickback rather than the insurance company submitting the lowest bid.

According to industry sources, such contingency agreements had been common in the industry since the seventies. But in the nineties, a Marsh & McLennan employee named William Gilman, who is identified in Spitzer’s complaint, stumbled on a way to make them even more profitable by basing them solely on the volume of business an insurance company received from Marsh & McLennan. (The more business Marsh & McLennan sent it, the larger Marsh & McLennan’s cut in percentage terms.) By the latter part of the decade, Marsh & McLennan had centralized this process in its Global Broking Unit, a move that allowed it to exert even more leverage over insurance companies, and to generate even larger contingency fees. Eventually, the firm’s brokers allegedly became so brazen that they began fixing bids outright. In a 2001 e-mail uncovered by Spitzer, one Marsh & McLennan executive advised an insurance company to send a “live body” to a meeting to create the appearance of competition, even though the outcome of the bidding process had already been determined. “Anyone from New York office would do. Given recent activities, perhaps you can send someone from your janitorial staff—preferably a recent hire from the U.S. Postal Service,” the Marsh & McLennan executive joked. In a June 2003 e-mail exchange, an insurance-company executive chafes at being ordered by Marsh & McLennan to come in higher than $850,000 on a bid with the container company Brambles USA, so as not to undercut AIG. “Doherty gave me song & dance that game plan is for AIG at $850,000 and to not commit our ability in writing,” the rival executive wrote of a Marsh & McLennan broker. “This is another AIG protection job.”

It’s unlikely that Jeff Greenberg would have had any direct role in these activities, given the timing of his ascent to the position of CEO. In fact, he is barely even mentioned in Spitzer’s complaint. (Marsh & McLennan declined to comment, and efforts to reach Greenberg were unsuccessful.) Still, the alleged wrongdoing appears to have accelerated on his watch, whether or not he had anything to do with it. According to a former top executive in a Marsh & McLennan subsidiary who interacted with Jeff on a periodic basis, news of Jeff’s appointment split Marsh & McLennan’s executive ranks into two camps: “There was a camp that felt it was a good thing to occur”—the thinking being that the Marsh & McLennan management had become too inbred and stagnant—“and there was a camp that was concerned about the Greenberg reputation, whether or not he would destroy the culture there.” In particular, says this executive, the fear was that Jeff would try to run Marsh & McLennan like an insurance company, where employees are more expendable because the company rises or falls on its financial assets, rather than as a professional-services firm, where “human assets are more important than the balance sheet.”

What the company got, in the end, was a little of both. Jeff went at the job like a man with something to prove, very quickly trying to raise the company’s profile by recruiting executives from top investment banks. But, culturally, Jeff seemed to make the company more like the insurance world he’d grown up in. “He was trying to, in his own way, be a new CEO, to shake things up,” says this same executive. At times he was “extremely demanding, just like his father.” Another former top Marsh & McLennan executive puts it this way: “People at AIG perform, and to some extent live a little of life in fear, wondering, ‘If I don’t deliver in this quarter, I’m on the street.’ … It’s much more binary, black-and-white, than Marsh would have been.” But this changed once Jeff arrived. “There was more leeway in the old Marsh … [Jeff’s] very aggressive.”

According to this same executive, the new aggressiveness created anxiety in the upper ranks of the company. “That may have caused some of the issues. People were scared to death of losing [their jobs]. Once you’re at Marsh, the feeling is that Marsh is the No. 1 broker. If you fail there,” your only option is to go work at an inferior firm. The Wall Street Journal reported that Roger Egan, president and chief operating officer of the company’s brokerage division, once told his managers, “Each time I see Jeff, I feel like I have a bull’s-eye on my forehead.” The company denies that Egan made the statement. But one of the former executives believes it rings true. “That wouldn’t surprise me,” says the executive. “All of a sudden, there’s a gigantic shift; you panic.”

This in itself is not necessarily a recipe for disaster. But if fear is going to be a primary motivating tool, as it is for Hank, you’d better make sure you know what’s going on at every level of the company, so that it’s not driving people to do things that could blow up in your face. Hank accomplishes this, to some extent, by micromanaging his company. The AIG executive holds annual meetings with the heads of each of his company’s divisions, where he and the executives go line by line over the division’s budget. Hank is also notorious for placing phone calls to unsuspecting executives multiple levels below him in the corporate hierarchy in an attempt to gather intelligence. Jeff, by contrast, was much more of a hands-off manager. “There was only one time in my whole career when I saw Jeff drop down into operations,” recalls one of the former Marsh & McLennan executives. Every one of the handful of former Marsh & McLennan executives I spoke with agreed that Jeff was unlikely to have had any knowledge of the bid-rigging activity. “I personally don’t think that Jeff knew anything at all about what was going on,” says one. But, adds another, “there’s no question there was a willful ignorance at Marsh. There were plenty of explosions along the way” that should have set off alarm bells.

Jeff also failed in another way in which his father excelled: his ability to take the necessary precautions when he felt he might be brushing up against a legal or ethical line. AIG is alleged to have participated in some of the kickback and bid-rigging schemes that Marsh & McLennan organized, but Hank took two crucial steps that are likely to salvage both his company’s reputation and its stock price. First, as early as 2002, AIG approached the New York State insurance superintendent complaining that it was being pressured by Marsh & McLennan to pay large commissions and asking for an investigation into the matter (even as it continued to pay them). Then, after Spitzer announced his investigation of the insurance industry in April, Hank launched his own internal investigation into the bid-rigging allegations, which resulted in charges being brought against two mid-level employees last month.

Marsh & McLennan, by contrast, kept insisting through its general counsel, William Rosoff, that it had done nothing wrong—right up until the day Spitzer filed his complaint with the State Supreme Court. It’s possible that Rosoff was acting on his own, without direction from Jeff Greenberg. But that wasn’t the assumption Spitzer’s lawyers worked under. “It would be weird, an anomaly, if [Marsh & McLennan’s] general counsel was setting the tone, deciding things,” says one Spitzer official.

The contrast here is almost poignant. In September, Spitzer’s office began lobbing subpoenas at the insurance industry, soliciting documents and asking to speak to executives with knowledge of certain activities; this is in part a ploy to get information from one company that will be useful in a case against another. The subpoenas came affixed with a two-week deadline, something companies typically see as a subject for negotiation. (Though less so in this particular case, under this particular attorney general.) “It’s less formalistic than you imagine,” says the official. “You send these things out, you get calls, ‘What is this? What do you want? When do you want it?’ ” As it happens, two of the first companies to respond with information about Marsh & McLennan—safely ahead of the deadline—were AIG and ACE, which Evan now runs. What might have prompted their swift cooperation? The official won’t comment specifically about the Marsh & McLennan investigation. But he allows that “what happens in situations like this is, prosecutors try to set up a race to come in. The first people in tend to get the most credit. It’s not a surprise if the recipients of the subpoenas vie with each other to see who can be first.”

In rushing to implicate Marsh & McLennan, executives at AIG and ACE may have been merely acting to protect themselves from Spitzer, the big bad wolf of corporate America. But does the fact that each of the three CEOs were Greenbergs, playing out parts in a long-running family drama, have anything to do with it?

It can’t be dismissed out of hand. Says one analyst who follows AIG, “[Hank’s] such a fierce competitor. If someone leaves, they’re a traitor. If you become a competitor, even worse.” Being his son does not, apparently, qualify as an exemption. It’s too bad Jeff never entirely learned to play the game this way.