At 5:20 on a Sunday morning in the summer of 1996, Sidney Frank—liquor baron extraordinaire, dapper elderly gent, CEO of the Sidney Frank Importing Co.—picked up his phone in a fit of inspiration. He dialed up his No. 2 executive, who listened in a groggy daze as Frank proclaimed, “I figured out the name! It’s Grey Goose!”

And so was born one of the most astonishing brands in the history of distilled spirits. Grey Goose vodka, invented from thin air that summer morning, had as yet no distillery, no bottle, and—perhaps the most pressing order of business—no vodka. Yet this past June, almost exactly eight years after Sidney Frank gave name to this nonexistent liquor, Grey Goose was sold to Bacardi for more than $2 billion. Cash. (To understand how much that is, consider that IBM’s personal-computer business, nurtured, honed, and advertised since 1981, recently sold for $1.75 billion.)

After the Grey Goose sale, everyone at Sidney Frank Importing Co. got a hefty bonus. Longtime SFIC secretaries were handed checks for more than $100,000 apiece. Grey Goose was a spectacular success. And now the ride was over. The only question left: What’s next?

Cut to a shiver-cold night in downtown Manhattan, not long after the sale. A team of SFIC employees are out pushing Sidney Frank’s new brand of the moment: Corazón tequila. They chat up pub and restaurant owners. They teach bartenders how to mix new Corazón cocktails. And then, in a small club in the meatpacking district, they run smack into the competition: Bacardi salesguys, making their own nightly rounds.

SFIC publicist to Bacardi salesguy: “What are you drinking tonight?”

Bacardi salesguy, swirling ice in highball glass: “Goose Orange, baby!”

Suddenly, the SFIC folks look a bit downcast. Consider their fate: Just a few months back, their job had been to drink (and promote) Grey Goose, which made them the most popular people wherever they went. A Grey Goose Cosmo here, a Grey Goose–and–tonic there. Then their beloved Goose got sold to these mass-market hacks from Bacardi (who’d tried, without much success, to launch their own superpremium vodka—an Estonian concoction called Türi—before they bought Goose). Now the SFIC team is compelled to push this unknown brand of tequila, all night, every night, on crowds that don’t know what it is and don’t particularly care to find out.

When I suggest to an SFIC vice-president that vodka is by definition odorless and tasteless, his face goes tight. “That is a dinosaur statement,” he says.

Sidney Frank doesn’t necessarily want to be in the tequila business either. Agave plants are notoriously fragile crops, and the fancier tequilas must be aged for a year or two, while vodka comes out of the still and is good to go. And in the distilled-spirits game, tequila plays in the second division, accounting for just 5.1 percent of the market. Vodka dominates with 26.5 percent, while rum has 13 and gin 7.

Making matters worse, there’s already a strong brand entrenched in the superpremium tequila category, Patrón.

But when Goose got sold to Bacardi, SFIC signed a stringent noncompete clause: It can’t launch a new brand of vodka or gin for the next four years. So tequila it is. SFIC will spend at least $3 million on Corazón marketing in 2005 and make it available to all sorts of influential crowds—at a VIP tailgate party at the Super Bowl, at the victory dinner for the Indy 500, and at the Junior League’s Winter Ball in New York. As the product becomes known, says Frank, “some idea will come to me that will push it forward.”

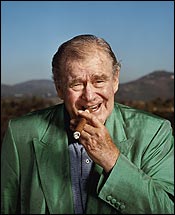

The odds against any new spirits brand are long. Some say the Grey Goose explosion was a fluke, a miraculous confluence of timing and trends. And whatever marketing tricks SFIC had up its sleeve last time—all the guerrilla promotions that Sidney Frank is famous for—everyone else is onto them by now. Given the fierce competition, can Sidney Frank, now 85, do it again? Of course he can. He’s done it not once but twice before.Born in 1919, Sidney Frank grew up poor in rural Connecticut, a farm boy who harbored a Gatsby-esque drive for social transformation. He wiggled his way into Brown University, where, for the first time, he slept on real bedsheets (not sewn-together flour sacks), and found himself surrounded by the children of the rich and powerful. Frank had to drop out of Brown after one year because he couldn’t afford tuition. (When Grey Goose was sold, he gave $100 million to Brown to provide financial aid for poor students.) But Frank made the most of his brush with privilege. Old snapshots show a handsome, broad-shouldered fellow, always in a coat and bow tie, hair slicked back in an impeccable part. Sidney Frank was a charmer, and he knew which people to charm.

In an interview with the Brown Alumni Magazine, on the heels of his massive donation, Frank was asked if he had any advice for the young Brown student. “If you meet any important people,” he said, “keep in touch with them … And marry a rich girl. It’s easier to marry a million than to make a million.” Through Brown friends, Sidney Frank met, and, in 1945, married, Louise “Skippy” Rosenstiel, whose father was chief of Schenley Distilleries (at the time a spirits-industry powerhouse). Frank went to work for the company, made his way up the corporate ladder, and then (after a family falling-out, and Louise’s death) branched out to start his own liquor business in 1972.

SFIC was no overnight success. Frank was forced to sell off personal assets (fine art, property in Antigua) to keep the company running. Early on, during the tough times, he would stroll around New York neighborhoods to see who was drinking what in the bars. Once, during a jaunt through Yorkville, he saw German immigrants downing something called Jagermeister, a 70-proof, odd-tasting liqueur from the Fatherland. It was no big seller, but the drink seemed to have a steady fan base, so Frank took a chance and secured the U.S. importing rights. Nothing much happened for the next decade.

Then, in 1985, for no clear reason at all, college kids in Baton Rouge and New Orleans decided Jager was cool. Just one of those things that happen sometimes. Kids being funny. It’s likely they chose Jager precisely because its taste was so horrific. The whole thing might have easily been forgotten by the next semester. But that’s not what happened.

Bill Goldring is chairman of Magnolia Marketing Co., which was SFIC’s distributor in Louisiana when Jager first hit. “Brands are a funny thing,” he says. “Corona beer started at the University of Texas, where kids were putting a lime in it. Then Jimmy Buffett was drinking it. Then it was the hottest beer in America. With Jager, we saw we were getting large orders because the LSU kids were drinking it. Then there was the newspaper story in the Baton Rouge Advocate.”

The story, at the height of LSU’s Jager boomlet, quotes kids calling the herb-infused drink “liquid Valium,” and theorizing that Jager was an aphrodisiac. When Sidney Frank saw this, he flew into action, assembling a team of hot chicks, dubbed Jagerettes, and dispatching them to New Orleans bars to hand out photocopies of the story. Frank also slapped up eight new Jagermeister billboards in the area. They displayed a wincing man and the words SO SMOOTH, playing on Jager’s ironic appeal. (I remember, back in high school, a friend’s college-age big brother had a T-shirt with the SO SMOOTH guy on it. We thought this was the pinnacle of cool.)

All over the country, Jager shots became a revered symbol of buck-wild partying, and the brand remains one of the hottest in the industry, growing at 40 percent a year. Yet not a single spirits expert I spoke with could explain the Jager phenomenon, beyond shrugging and calling Sidney Frank a “promotional genius.”

“It’s a liqueur with an unpronounceable name,” says Ted Wright of Liquid Intelligence, a beverage-marketing firm. “It’s drunk by older, blue-collar Germans as an after-dinner digestive aid. It’s a drink that on a good day is an acquired taste. If Sidney Frank can make that drink synonymous with ‘party’—which he has—he can pretty much do anything.” Pretend for a moment you’re the man himself—Sidney Frank, liquor legend. First, you should be aware: You transact much of your business from bed, wearing pajamas and smoking a cigar (it is written into the prenup with your second wife that you are permitted to smoke cigars in bed). When not in bed, you wear a bow tie at all times. Also, you maintain a phalanx of full-time golf pros, at a cost of perhaps half a million dollars a year, simply so you can watch them play the game. You can’t swing a club yourself anymore—too old—so you golf vicariously, directing your pros shot-by-shot down the course. “Hey kid, hit a three-wood to the right of that water hazard,” etc.

To the business at hand. The year is now 1996, and, flush with Jager’s success, you’re ready to invent a new vodka from scratch. Why? Because the microbrewed-beer craze is giving way to a new age of sophisticated cocktails. Dot-com dollars are begging to be spent ostentatiously, at expensive nightclubs. Herein lies opportunity.

We’re out flogging Corazón at a club on the Bowery. The scene is clearly rife with Influencers. On my way in, I brush past Ethan Hawke.

As you lean back in your golf cart, watching another perfect chip shot bounce up onto the green, you ponder the fact that the premium vodka right now (in 1996) is a brand called Absolut. When it was first introduced, Absolut’s high price was considered outrageous. But it’s had great success (with its iconic, artsy ad campaign), and it now sells for the steep, steep price of about $17 a bottle.

So, to steal away Absolut’s market share, your unborn new vodka should undercut this price, correct? No, you think, chomping your cigar as you watch a 30-foot putt roll straight into the cup. Why don’t I price my vodka extravagantly higher than Absolut, at wildly more profitable margins … and steal Absolut’s market share that way? This was the great insight of Sidney Frank (and not only him: The makers of Ketel One vodka had the same basic idea). Frank could see that there was a product missing from the shelves. Here were all these vodkas, in the $15-to-$17 range, vying to be the premium brand (with Absolut mostly winning). Frank just sidestepped the fray altogether and charged an unheard-of $30 a bottle. The markup amount was pure profit. “He was the first person to see,” says an executive at rival Bacardi, “that there was a superpremium category above Absolut, if you had a good product story.”

In this story, the name came first—as it so often does when image is the paramount concern. Frank recalled he’d once sold a Liebfraumilch named Grey Goose back in the seventies. These were German white wines that were briefly hip but faded into oblivion. “I remember there was always something in the name that had magic with the consumer,” says Frank. (It may also be that Frank liked the name because he already owned the worldwide rights to it.) Frank gathered his lieutenants at the company’s New Rochelle headquarters. “Go to France and come back with a vodka,” he said. So they met with cognac distillers, whose business had slowed. The stills were switched to vodka, and at last there was an actual product.

But why France? Doesn’t vodka come from Russia, or perhaps, in a pinch, Scandinavia? “People are always looking for something new,” says Frank. It’s all about brand differentiation. If you’re going to charge twice as much for a vodka, you need to give people a reason.

“Nietzsche explains that human beings are looking for the ‘why’ in their lives,” says Wright. “Here at Liquid Intelligence, we refer to this ‘why’ as ‘the Great Story.’ The Great Story must be enticing, memorable, easily repeatable, and about what you want your brand to be about.”

For Grey Goose, the brand was about unrivaled quality. Grey Goose’s Great Story hinged on the following key points:It comes from France, where all the best luxury products come from. It’s not another rough-hewn Russian vodka—it’s a masterpiece crafted by French vodka artisans.

It uses water from pristine French springs, filtered through Champagne limestone.

It’s got a distinctive, carefully designed bottle, with smoked glass and a silhouette of flying geese. It looks fantastic up behind the bar, the way it catches the light (and Frank made sure to give the bars big, 1.75-liter bottles, to grab attention). It sure looks expensive.

It was shipped in wood crates, like a fine wine, not in cardboard boxes like Joe Schmo’s vodka. This catches the bartender’s eye and reinforces the aura of quality. Never forget the influence of the bartender.

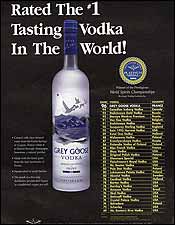

It was named the best-tasting vodka in the world by the Beverage Testing Institute in 1998. (Granted, this pronouncement can and will be doubted. But it was nonetheless touted relentlessly in a series of Wall Street Journal ads.)

And now the most important piece of the story—the twist that brings it all together: Grey Goose costs way more than other vodkas. Waaaaaaay more. So it must be the best.

Pause for a reality assessment: Certainly, Grey Goose is a very good vodka. But is it really “the best”? Pace the Beverage Testing Institute, I’d venture that the answer is, ehhhhh, maybe. Of course, when I suggest to an SFIC vice-president that vodka is by definition odorless and tasteless, and thus one vodka couldn’t be much better than the next, his face goes tight. “That is a dinosaur statement,” he says, speaking slowly, then lectures me on water-filtration processes and Champagne limestone and special grains and such.

“Yes, some people may taste a difference,” says Wright of Liquid Intelligence. “But you’re talking about a grain-neutral spirit. The FDA definition is pretty narrow. At an elemental level, there is no difference. And anyway, you can’t possibly taste it when it’s in a Cosmopolitan. Grey Goose is about quality because Sidney Frank said it was about quality.”

And said it to the right people. Those ads were placed in the Wall Street Journal, not Newsday. Even more important to the campaign was event marketing—getting Grey Goose into the hottest clubs on the hottest nights, in the hands of the hottest people. “You need to influence the influencers,” says Wright. These are the obsessive arbiters of taste who like to tell their friends what to buy. When they have a Great Story to tell, they’ll tell it convincingly and often. In the classic flowchart, Influencers talk to Early Adopters (“Want to be cool but don’t have the time,” as Wright describes them), who talk to the Early Majority (“Suburbs”), who talk to the Late Majority (“Middle America”), who talk to the Laggards (“Just now buying a CD player”).

As the Influencers peddled the Grey Goose tale far and wide and people began to call for it in bars, a great thing happened—the characters on Sex and the City pointedly called for Grey Goose Cosmos. In the battle for vodka supremacy, this was the atom bomb. The war was over. Grey Goose had won. Though Grey Goose is a product of Sidney Frank, spirits savant, it’s also a product of its age. We live in an era of luxury. The word luxury—in this context—refers not to our standard of living but rather to a highly successful sales concept.

Luxury, in a consumer sense, means spending much more than you have to. Your reason for doing this could be that you demand the absolute highest quality, because you can genuinely tell the difference. As Cornell economics professor Robert H. Frank (no relation to Sidney) points out, “You can buy a car that does zero to 60 in 3.9 seconds. Or you can spend $445,000 to buy a Porsche that does zero to 60 in 3.7 seconds. It’s a real difference, and some people will pay for it.”

But small quality differences like this are not why most people buy a luxury product. Frank, author of the book Luxury Fever, observes that the thirst for luxury trickles down to those who can’t really afford it. Frank calls this the “expenditure cascade.” We all spend more in an effort to keep up with the guy who’s one rung above us. This means we buy bigger houses to keep up with the neighbor’s mansion. It also means we buy superpremium vodkas, to keep up with the guy who’s next to us at the bar.

This is what SFIC is banking on. The company’s decided its interests lie solely in the superpremium categories—where margins are higher and volumes lower. (Even Jagermeister is technically superpremium, despite its blue-collar image. It’s priced above its competitors in the liqueurs category, such as Bailey’s and Kahlua.)

But SFIC will never again have the niche to itself. These days, every spirits marketer is diving headfirst into superpremiums. Absolut just launched Level, a new superpremium vodka, only to see the simultaneous launch of Stolichnaya Elit (which will sell for a dizzying $60 a bottle). You might wonder where the price escalation will stop or if it will stop at all. People don’t seem to blink at paying high prices for a cocktail in a bar (as opposed to in the liquor store, where they tend to be more price-conscious). As long as your high-end brand has a credible story behind it, you can keep hiking its margins, and consumers will follow. The trend is known in the industry as “trading up.”

“Consumers are drinking less, but drinking better,” says Michael J. Branca, a beverage-industry analyst at Lehman Brothers. The evidence is that volume sales of spirits have been flat, while dollar revenues have soared. According to Branca, this stems from a worldwide trend toward health and wellness, as well as a growing consumer demand for “everyday luxuries,” which includes things like Starbucks Frappuccinos.

The best thing about the everyday luxury business is that an awful lot of Americans can afford a $15 cocktail, whereas real luxuries, like a $3,500 Rolex, have a much smaller market. And the margins for superpremium spirits are fantastic. Remember, these high-status luxury products are more than half water.

It’s possible the trading-up trend could reverse, and we’ll all drink Joe Schmo’s vodka as some sort of trucker-hat statement. But liquor experts think the superpremium category is pretty safe. The reason is that Grey Goose and its ilk do not rely on mere “coolness,” which is fleeting and hard to pin down. They’re chasing after “bestness”—a consistent target even if it’s hard to hit. There will always be a large subset of drinkers who want to be drinking “the best,” because bars and nightclubs are places to be seen. Places to prove you’re a player. “Spirits is an image-driven category,” says Branca. “We’re acutely aware of what we’re drinking in the presence of others. That’s why it’s so important to have strong on-premise promotions with influential consumers.”

Thus we’re out on this freezing winter night, hawking Corazón at a club on the Bowery. The scene is clearly rife with Influencers. On my way in, I brush past Ethan Hawke.

Over in a corner, the SFIC team has set up a bar serving free Corazón tequila. There’s a Corazón ice sculpture and several babe-alicious Corazón girls flitting about with margaritas. The whole thing’s a $2,000 outlay from the marketing budget.

Though tequila has a strong frat-boy affiliation, as a salt/lime/bodyshot-off-drunken-coed’s-clavicle kind of item, it too has been caught in the trading-up trend. Sales have nearly doubled in volume since 1990, and the margarita is frequently identified by bar and restaurant owners as the most popular cocktail in America.

Corazón began outside the Sidney Frank empire, in the mind of one Frank Arcella, sole proprietor of Arcella Premium Brands. Arcella knew his one-man outfit couldn’t compete in the high-stakes vodka category. But in superpremium tequila, he had a fighting chance.

Arcella toured tequila plants in Mexico and settled on one in the highlands of Jalisco. It owned its own agave fields (a major consideration, as agave supply can fluctuate wildly) and aged its tequila in dedicated, tequila-only barrels—not reused sherry and bourbon barrels, as is often done. The product was good, and the management was reliable. So Arcella struck a deal.

He then brainstormed names and decided on Corazón de Agave (Heart of Agave) because it suggested high-quality ingredients, and because the word heart might offer good marketing angles. At the plant, Arcella was shown hundreds of existing bottle prototypes and chose one with a distinctive skinny neck. “You save half a million dollars you would have given to a bottle designer,” he says.

It’s the sort of gut decision Sidney Frank made his fortune with. To me, it’s astonishingly cavalier. (I’ve seen Coca-Cola execs give PowerPoint presentations about how they hire naming agencies and focus-group every single design decision.) But Arcella is no fool or hayseed. He spent 29 years at Seagram’s, reaching executive vice-president. He says brand creation is simple: product, package, name, marketing plan. “This is not rocket science,” he claims. Perhaps in the fickle world of luxury liquor, it’s better that one man make all the decisions. It results in a more distinctive, memorable product—one that feels less like a product for the masses.

Arcella actually went to Frank early on in the Corazón time line, to see if Frank had any interest. But it wasn’t until a few years later, in 2002, that Frank decided to buy Corazón. It’s not hard to see why. The Corazón brand blueprint looks exactly like the one for Grey Goose. Corazón can claim, with a modicum of credibility, that it’s the best product out there (it also got superlative marks from the Beverage Testing Institute, which will soon be touted in an ad campaign). It’s got distinctive packaging. It’s priced above most competitors.

And so here we are tonight, out on the town, influencing the Influencers. At one bar, we get “bottle service,” buying an entire bottle of Corazón for a mere $310—plus mixers for free!—and displaying it prominently on our table.

Even with all this, it’s hard to foresee the sequence of events that might turn Corazón into a real competitor to Patrón. But the industry knows better than to bet against Sidney Frank. “Patrón has good imagery, it’s a strong brand, and it’s set up nicely,” says Michel Roux, the liquor exec who crafted Absolut’s long reign. “Of course, you could have said the same thing about Ketel One, back before Grey Goose took off.”

If Corazón fails to overtake Patrón, Frank has fallbacks, like a new line of cognacs, which will come in flavors like pear and apple, aimed at what analysts term the “urban” or “hip-hop” market. Frank has some experience with this market—he backs a side project with rapper Lil’ John, marketing an energy drink called “Crunk!!!” It’s also a market where conspicuous luxury consumption is on the rise, and the prices are high. The best cognacs are often three to six times more expensive than anything else behind the bar.A new line of rums is also in the offing. Rums are widely believed to be the next vodka, as they’re also adept at soaking up flavors and acting as the base for a wide range of cocktails. SFIC plans to import its rums from Australia, to break from the herd of Caribbean rums. Tentative name for the line of rums: White Pelican. “It’s an endangered species,” says Frank, “and my wife likes the sound of it.”

When I asked a Bacardi executive, he said that rum doesn’t really have a superpremium category. That’s probably what Absolut would have said about superpremium vodka back in 1996.