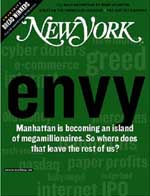

If you are standing still while others are getting richer, are you in fact getting poorer?

This question might be considered New York Zen, a modern, urban riff on the age-old “If a tree falls in a forest” koan, except that in 1999 New York, this question may indeed have an answer, even if the poverty in question is only in our minds.

We’re nearing the end of the greatest stock-market boom in world history, and as the Dow has marched from around 2,500 in 1991 to 11,000, the Myth of the Roaring Nineties has developed. Unlike the insidery, elitist, Boesky-remote eighties boom, this was supposed to be our day in the sun. They called it the People’s Boom. It was a market run of, by, and for the “little guy,” which crept “from Wall Street to Main Street,” as we heard all too often. In the nineties, everyone got in the game.

Never mind that most of us got in the game – to the degree we did at all – simply by channeling off a tiny bit of our biweekly paychecks into some stodgy blue-chip fund for our retirement. The Myth quickly centered on the Jed Clampetts of nasdaq, the neophytes – or “newbies,” in the current day-trader terminology – who struck oil with the ease of a keystroke on Datek. These days, the air is thick with stories of the florist who abandoned her day job to pull down $150,000 a year day-trading, or the Jersey kids who left college and sold out their Website for millions, or most notably, the 32-year-old journalist – journalist! – who went from futon-living to Roger Clemens’s income bracket the day his company went public.

In this climate, we’ve incessantly been told, everyone could get rich.

Except that not everyone did get rich. Few people I know even felt the heady rush of life inside the Boom. A friend of mine, a successful publishing executive, wears Hugo Boss suits and summers at an East Hampton rental. Still, there’s something missing: “I’ve got a cousin up in New Hampshire who bought eBay at like $8, and it went up to, whatever, $164 overnight. Meanwhile, my wife and I have been sitting on the side, keeping our money in these safe, boring investments, trying to hoard enough for a down payment on a place on the Upper West Side. But the apartments that we’re looking at have gone up 40 percent in the past year. By the time we can afford the down payment, we can’t afford the apartment. Now my wife and I are like, ‘What happened?’ We feel like the Boom’s almost over, the crash has got to come one of these days, and we just missed it.”

Does he feel envy or resentment?

“No, I don’t feel resentment,” he says firmly. Then he stops. Reconsiders. “Well, envy? Maybe. Yes, I feel envy. It’s like, ‘Where were we while all this was going on?’ “

Of course, stocks as a whole are far from dead. Lately, guys on Wall Street Week have even begun talking about a Dow 40,000 with a straight face. But what suddenly feels as if it’s on life support is the definitive nineties dream, the vision of overnight wealth without work.

The people who feel left out of the whole mania are something of a new subclass. They’re ambitious people from good schools with good jobs who assumed, back when the nineties started, that they would just sort of matriculate into the upper middle class, only to find that the Boom changed the rules of entry. First, the reality of the Boom changed the price of housing, which is any New Yorker’s clearest prism through which to view his own success in life. The confidence that didn’t get splattered when we had to downsize our housing dreams were further diminished when the very definitions of the words wealth and success started to change the way we looked at ourselves. We became, somehow, members of a new silent majority. A “majority” as a matter of basic mathematics – only 28 percent of Americans have more than $10,000 in the market – and “silent” for an even more basic reason: We feel just a little bit stupid.

“The ads by places like Discover Brokerage, you know, the fat guy behind the bar who made millions in the market, are just annoying,” a friend not long out of law school tells me. “I’m 28, I’ve got student loans, and I could only recently afford a measly 3 percent salary deduction for my 401(k). Sure, the returns are good. But who cares? On the small amount I can afford to put into them, the gain is completely negligible. What any ‘boom’ means to me is simply that I still have a job.”

In another not-too-distant era, we would have been yuppies, scorned for buying up every last exposed-brick two-bedroom in the Village. Now, even though our income has been rising steadily, we may not be able to afford the $650,000 a nice two-bedroom goes for these days – in New York in the late nineties, in other words, you can get ahead and still fall behind. The old yuppie dream – nice apartment, Hamptons rental, good restaurants two or three nights a week, for instance – is increasingly accessible only to those who are making major money on Wall Street or Silicon Alley.

If you feel like you’re on the outside looking in, at least you’re not alone: More than 40 percent of Americans own no stock, not even through a retirement account. New York University economist Edward Wolff found that the country’s richest one percent have accrued a staggering 86 percent of the stock gains since the early Reagan years.

Mark Weisbrot, a Washington-based economist and syndicated columnist, recently sat with a panel of prominent business journalists to tape a show on C-span about the “new economy.” “They were all saying that the big thing about the new economy is that everyone owns stocks now,” says Weisbrot, “and I just said, ‘Look, 57 percent of the country doesn’t have a penny in stocks, not even in retirement accounts.’ Stock ownership has exploded relative to where it used to be, back when almost nobody owned stock, but what’s really new about the new economy is that the gains from dramatic economic growth are going to a small segment of the population.”

As one friend, a screenwriter in his early forties, explains, “I stayed conservative all these years because I don’t have anything to gamble. My nest egg is so small, I could quintuple it, and it still wouldn’t really mean anything. But I could lose it, and the loss would be huge.”

Not even most lawyers I know feel the thrill of the oil-patch gusher. One I know has degrees from the best schools. He even does Wall Street-oriented tax work at a top midtown firm. Nevertheless, he feels like his invitation to the great Roaring Nineties bathtub-gin blowout got lost in the mail: “I feel the Boom has benefited a lot of people more than me, and all the stock talk is getting so annoying, particularly in the gym. These guys have a Golden Storybook knowledge of economics but can’t shut up about Amazon or anyfuckingother.com. It’s like listening to a fundamentalist Christian explain the strata of the Grand Canyon in the context of talking about the great moments in the Book of Genesis. All of which is fine, so long as the punters don’t start wailing when the market corrects.”

“There is so much hype, so much press, about the ‘little guy’ who made so much. This puts a lot of pressure on people,” says Marlin Potash, a psychologist and a corporate psychological consultant. “I hear this all the time. I work with a Manhattan population. These are educated, involved, alert people who read everything they can get their hands on. They’re watching Wall Street Week, they’re on the Internet, they’ve read about the IPOs that have passed them by. They know their next-door neighbor who invented some little something for the Internet has a company that’s losing money but has gone public. He now is worth $40 million. These folks are feeling not just left out of the boom but stupid. It’s more than just the financial stress. They’re kicking themselves, wondering, ‘Am I the only jerk out there? I’m still working a real job.’ There’s a sense that the Boom has passed them by.”

Potash says the stress can be extra acute on the high achievers who took the traditional route to financial success, only to themselves be damned to traditional rewards: “In my practice, I see a lot of people who work on the periphery of these Internet-start-up-type businesses – the lawyers, the investment bankers. They’re working with these 28-year-old guys making zillions of dollars, and saying, ‘I’m making fees, and you’re making millions.’ “

As Manhattan-based certified financial planner Stanley Chadsey says, “People are not happy with 20 percent gains when the guy next to them is getting 150 percent gains.”

Walk through Bryant Park on a springtime Thursday at lunch and you can uncover shades of this fin de boom angst, even among perfect strangers sunning themselves in Italian suits.

“I wish I had more money to put in the stock market, but I’m just a young guy starting out, and I only have so much disposable income,” says Carsten Jerrild, 29, a software salesman. “I know a couple of people who are sitting on millions right now because of some stock options they’ve had. One guy that works for us, his wife works for Cisco Systems. Her options were worth $2 million overnight. I guess that makes you feel a little downtrodden. Every day you start seeing people making a killing, you read the stories about some guy working from TheStreet.com making $32,000 a year, now he’s worth $9 million because they went public or whatever. You see those stories, and I’m like, ‘God, here I am. I’m 30. Why aren’t I a millionaire?”

“You hear a lot of stories, some of which are hype,” chimes in Timothy Thompson, 36, a telecommunications executive sitting alongside Jerrild. “The media is sort of distorting things. A waiter or someone who has a service-level job invests in some Internet stock that went through the roof, but that same stock crashes several months later. They don’t tell that last part of the story. I work with a guy who was recently complaining to me that he lost $40,000. His Internet stocks crashed a few weeks ago.”

Mike Davis, 25, is an executive for Lord & Taylor. “I feel I’ve come in on the tail end of the stock-market boom. I should probably get more into investing in individual stocks. I have lunch with a few friends of mine, and they always talk about having made a couple thousand here, a couple thousand there, from trading online. It makes me feel that I should probably be more involved in investing. I want to share in the wealth. But I only hear the good stories, and I’m sure there’s the other side, too.”

Home from the park, I try to sketch out the broad themes of this new social class. On a clean white sheet of paper, I scribble:

Envy.

1-Bedroom.

Too Much Social Mobility.

The phone rings. I’m drawn away. By the time I come back to it, the sheet is a list no more, but a haiku – even if it is a few syllables short. I hang it on my bulletin board. It makes me feel better, somehow.

“There are a lot of people who are salving their open wounds about having missed out,” Potash says. “By saying, ‘Things are coming crashing down, and I’m not overextended and I still have my head screwed on straight,’ some of that is a self-protective mechanism: ‘It couldn’t possibly keep on moving at this pace, because if it does, I’m just too scared.’ “

She adds that the jones to keep up with the Joneses is harder on men than on women, who tend to be more willing to admit what they don’t know and more willing to try to learn the new rules of the new game.

And the sense of missing out festers deep in the subconscious. Says Anita Weinreb Katz, a Manhattan psychologist who’s practiced since the sixties: “People nowadays already work longer hours. They’re more tense. There’s more competition. A lot of people are hooked by this awful compulsion to keep up, and do feel envy. Envy is a very destructive emotion. It’s not something that leads to growth. You hate the person you envy. You want what that person has, and you want to destroy the person who has it. It’s a very primitive feeling. Even if it’s not acted out, which it’s usually not, it’s a very destructive internal process. You feel guilty. You hate yourself. And then you can’t even do what you can do, because it’s not good enough, because it’s not as much as that person has and does.”

It must be said that life for those who didn’t make a killing is not really so horrible. Anxieties are in some ways misplaced. In the new book Myths of Rich & Poor, authors W. Michael Cox, of the Federal Reserve in Dallas, and Richard Alm argue that the Boom’s rising tide actually has indeed lifted all Chris Crafts. In terms of material comforts – cars, dishwashers, TVs – the poor of today, families who make $13,000 or less a year, have as much stuff as the average household did in 1971. While real wages have fallen 15 percent since 1973, all you have to do is expand the definition of wage to include fringe benefits like health care, retirement contributions, and stock options, and wages are actually up 17 percent since the Nixon years.

The median net worth of households – the total value of everything they own, including their home, their stocks, their computer – has doubled in that time. (The authors did not specifically explore the rage of New York’s one-bedroom class, though they did emphasize that the average new home in the non-New York hinterlands is 40 percent bigger these days).

A few years ago, I was at a party up near Columbia, hosted by a friend who was working on a graphic novel and attended by an unusually humane group of young New York professionals. Everyone had gone to a good school. Everyone had a good job. No one was making money.

I ended up having an extended chat with an amiable, square-jawed guy with a quarterback’s name and a job at the Wall Street Journal. We were two young journalists, working hard. We talked about the inevitable allure of selling out, making our score. We talked about how we might someday, and where we could. Corporate-crisis P.R. was mentioned.

In the ensuing years, I started to hear his name a fair amount. A couple of weeks ago, I heard it a fair amount more than that. His name is Dave Kansas. He is the editor of TheStreet.com, 32, and one day in mid-May, his worth grew by $9 million. He’s a folk hero.

Soon after the IPO, Kansas told one reporter, “Everyone expects me to buy them dinner now. And of course I do because I’m from Minnesota.” He still had a hole in the toe of his right loafer. He still slept on a futon. But he did want a new titanium bicycle.

Kansas clearly understands the fundamental rules of winning the Internet lottery in the nineties: Act normal. Seem regular-guy-ish. Emphasize humble origins.

But Kansas is hardly the only millionaire weaned on Martha Quinn wandering around New York. Another friend of mine has yet another friend who rode the IPO wave at an Internet company. Now he’s the happy Mr. Moneybags. He takes big groups of friends on mountain vacations and foots the bills. He buys vast dinners. “He’s my sugar daddy,” my friend says. “It’s like traveling with Leo DiCaprio – actually, he’s more generous.”

A couple of weeks ago, another one of my Dumpie friends joined the ranks of the ex-Dumpies. A mid-level employee at barnesandnoble.com, he strolled into work one day and found out it was the day, the hotly anticipated IPO. Christmas Day had come, right here in the middle of baseball season.

“We didn’t even know today was the day,” he says. “We just came in and got a note saying today is the day, just hang on and be cool.”

Like all employees, he had been given a select portion of stock options, which he had the right to “buy” incrementally at a series of future dates for a small fraction of the shares’ initial price of $18 apiece. Barnesandnoble.com, however, was not TheStreet.com, which issued at $19 and closed at $60, minting a sudden new cyber-peerage. On the first day of trading, the stock went to $25. My friend seemed a bit disappointed but could hardly complain.

“My girlfriend’s company went public a year ago. That was the big deal. Everyone made a lot of money. The stock shot up to like 60, then it shot up even further,” he says. “That was just crazy, everyone just sitting around waiting to, well, sell, basically. That’s not the case here. The options don’t vest until the first.” He considers. “I thought the price was going to go much higher. You know, I’m kind of thinking that this might be the beginning of the end for Internet IPOs. This might herald a return to normalcy, where not every stock just jumps to $150.”

In fact, he gets only a quarter of his stake every year. Which, of course, is hardly bad. “If I were to cash it in, take my loss and everything, get the cash, pay the fee, pay the taxes, it would be an okay down payment on an apartment – and this is just 25 percent of what I get. So far, though, my friends haven’t really teased me about this. Because it’s not so much money that you’re alienating anyone. I have friends who became millionaires. And it’s almost like you don’t want to joke about that with them. It’s just a big deal. With this, it’s not threatening. It’s not going to change anyone’s lifestyle.”

But talking to him that day, there was a tiny but perceptible divide between us, suddenly. As if we were living in a Calvinist universe, it seemed that some deity had decided he liked my friend just a little bit better than the rest of us, just a smidgen. Maybe my friend also sensed the divide. He certainly knew how to respond. We agreed to meet for drinks, and he didn’t have to be told what to say next.

“I’m buying.”