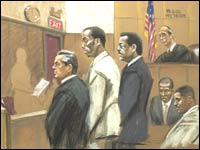

It was the kind of moment defense attorneys live for. At a little past six on a Friday evening last March, Ben Brafman stood next to his high-profile (and highly controversial) client, Sean “Puffy” Combs, in a seventh-floor Manhattan courtroom and braced himself for the verdict. The intense pressure of a two-month trial that featured wall-to-wall media coverage, 60 prosecution witnesses, and the prospect of a fifteen-year sentence had clearly gotten to him. Brafman had barely slept in the three days the jury had been deliberating.

When jury forewoman Brenda Kronenberg spoke the words not guilty on each of the five charges stemming from a shooting in a Times Square club, Brafman reflexively shouted “Yes!” hugged his client, and buried his tear-streaked face in his hands. Later, he would say he was so overwhelmed he thought he was going to collapse.

As Brafman took his victory lap around the talk-show circuit, the whole episode seemed to reinforce the notion that the best legal-defense talent regularly trumps public opinion – hadn’t the press virtually convicted Puffy, even as his glamorous girlfriend, Jennifer Lopez, deserted him? – not to mention the government’s prosecutorial strategies. But even as Brafman was soaking up the accolades for his courtroom performance, he knew something most of the public didn’t: Not only are come-from-behind defense victories becoming more and more difficult to achieve, but simply going to trial has become almost prohibitively risky. One of the reasons Brafman was so overcome with emotion when the Combs acquittal came down was that it was so rare – so rare that many of the best criminal lawyers in town are ready to quit.

According to Brafman and dozens of other defense attorneys I talked to, the criminal-justice system has undergone a profound transformation. In fact, Brafman’s big win was an anomaly, and the era of the superstar defense attorney, part gladiator and part performance artist, may be coming to an end.

Criminal-defense attorneys maintain that, with the exception of the most minor offenses or the most serious – and when the accused is a celebrity – actual trials are almost rare now. Changes in the legal system have given prosecutors the power to exact extraordinary penalties from defendants who choose to go to trial and lose. The deck is so stacked against defendants who plead innocent, they say, that the average defendant doesn’t have the luxury of taking his case before a jury. Why fight, when the chances of victory are small and the penalty for losing is huge? Everyone is looking for a deal.

Nowadays, defense attorneys argue, justice is bartered in the prosecutor’s office, not fought for in a courtroom. “All the skills I had developed as a litigator can no longer be put to use as a criminal attorney,” says Joel Rudin, who at 48 has been practicing for nearly 25 years. “The primary skill needed for doing criminal work is as a negotiator to deal with the prosecutors. But since you’re not on even ground with them, you’re not so much negotiating as pleading. The system has totally perverted the values a lot of us grew up with.

“Practicing criminal law,” Rudin continues, “has become draining, dispiriting, and completely unsatisfying.”

“The prosecution wins probably 98 percent of the time,” says defense lawyer Richard Levitt, who grew up the child of two lawyers.

Hugh H. Mo, a former deputy police commissioner and Manhattan prosecutor who’s now a defense attorney, puts it this way: “Nowadays, if you get caught up in the criminal-justice system, they’re gonna take a piece of your ass – one way or another.”Over the past two decades, the justice system has been armed with enormous weapons, weapons designed to ensure not only the arrest of criminals but their speedy conviction and long-term incarceration as well. No budgetary or legislative resources have been spared. There are now hundreds of federal crimes (think securities fraud, the Internet, money laundering, child pornography, and so on), whereas once upon a time federal offenses were pretty much limited to kidnapping, bank robbery, mail fraud, and treason. New York’s penal code has been expanded from about 200 pages to more than 600. When Hugh Mo was an assistant district attorney in Robert Morgenthau’s office in the early eighties, for example, there was one criminal investigator and about 150 prosecutors. Today the office has 80 investigators and nearly 600 prosecutors.

And prosecutors, meanwhile, have been given an arsenal that includes measures like mandatory minimum sentences, the Rockefeller drug laws, three-strikes statutes, repeat-felony-offender rules, and the federal sentencing guidelines. While no rational person would like to see a return to the permissiveness and lack of accountability that used to be the order of the day, the overwhelming power of the criminal-justice system has raised a compelling question: Has the presumption of innocence and the constitutional guarantee of a trial by a jury of one’s peers been compromised by measures designed to speed the accused through a system with fewer opportunities to escape?

“Everybody knows now that if you go to trial and get convicted, you’re going to get massacred, you’re going to get the maximum sentence allowed,” says Murray Richman, the dean of defense attorneys in the Bronx courts. “Even innocent people often aren’t willing to risk fifteen or twenty years or more in jail by going to trial. Not when they can get it down to one to four if they plead.”

The most desirable currency (and the real wild card) in this criminal-justice flea market is cooperation. The best deals are available when a defendant is willing and able to turn someone else in or provide useful information about other crimes. “What we really have are two systems now,” says Rudin. “One for cooperators and one for noncooperators.”

Rudin, a pleasant-looking man with bushy gray hair and an earnest, concerned manner, tells the story of a guy who was charged with playing a key role in bringing several thousand pounds of cocaine into the U.S. and trucking it across the country. He was facing 25 years to life, according to the guidelines, for his crimes. Rather than go to trial, he gave information to the government, and in return he got a term of six and a half years.

Another defendant before the same judge was a man in his fifties who was charged with buying one kilo of cocaine for $3,000. As it turned out, what he actually got was not cocaine but cocaine base – crack. The system treats one kilo of crack the same as 100 kilos of coke, so the guy was facing fifteen to twenty years. But his predicament was made even worse by two factors. He wasn’t in the drug business, so he had no one to inform on and no information to peddle for a deal. And he wanted to fight to prove what he claimed was his innocence.

So he rolled the dice and went to trial. He lost and was sentenced to fifteen and a half years. The prosecutor had offered him a plea up front, for which he would have gotten three to five years. And if he’d had information to trade – or been willing to work on the street as a government informant – he could’ve gotten the whole thing reduced to just one year. At sentencing, the judge told the prosecutor she’d like to give him a lesser sentence than what the guidelines mandated. The prosecutor actually moved for a stiffer sentence and said he’d appeal if the judge reduced it.

“The point here,” says Rudin, “is that the guidelines haven’t resulted in uniform sentencing, which is the reason they were adopted, and if someone has the temerity to actually exercise their right to trial, the government will make them pay for it if they lose.”

The criminal-justice system began to change rapidly in the mid-eighties, when the federal sentencing guidelines were adopted. An unprecedented crime wave had been raging across the country more or less since the late sixties, and elected officials – this was the Reagan era – decided the time had come to do something about it.

The idea was simple: If someone was convicted of a federal crime – say, bank robbery – he would serve a specific prison sentence, regardless of how nice he seemed to be, who the judge was, or how good a lawyer he hired. The intent was to ensure uniformity – fairness – in the imposition of sentences.

The state courts also ratcheted up their sentencing rules, adopting statutes that called for mandatory minimums. The draconian paradigm was established by the the Rockefeller drug laws adopted in 1973. “Back in the early seventies,” says Jim Kindler, chief assistant D.A. in the Manhattan D.A.’s office, “there were only three crimes that had mandatory sentences: murder, kidnapping, and high-level narcotics. For all other crimes, the judges had significant leeway. That’s all changed.”

Because the guidelines mandate serious prison terms, many criminals facing these double-digit sentences don’t want to go to trial. It’s too risky. They’d much rather plead guilty and make some kind of deal for a shorter sentence.

This gives prosecutors unparalleled power and has turned judges, many lawyers argue, into little more than functionaries. Federal judge Jack Weinstein, who actually had refused for a period of time to handle drug cases because of the lengthy mandatory sentences, says that while judges do still have some latitude – “We have a variety of devices available to us to exercise discretion and to depart from the sentencing guidelines,” says Weinstein – prosecutors have the upper hand. “Where the power has really shifted to the prosecutors is because they’re the ones who can offer a defendant a deal.”

“Defense lawyers really feel like they have no job anymore. It’s like all the lawyering’s been taken out of being a lawyer,” says Ellen Yaroshefsky, a professor at Cardozo law school.

And, of course, it means that the demand for high-price legal-defense talent has dried up. Not only do the lawyers get to try cases much less often, but their fees have been steadily falling as well. Since many accused criminals know as soon as they’re arrested that they’re going to make a deal, why spend a lot of money to hire an expensive private attorney?

It’s also taken much of the challenge – and all of the sport – out of defense work. “This work used to be fun,” says Rudin, “but the fun was in competing head-to-head on a relatively level playing field with the prosecution, trying to be the best advocate you could for your client. But that’s no longer realistic because the prosecutors hold all the cards and the opportunities for success are so small. It’s become virtually impossible to fight the system.”

Consequently, Rudin says, very few people do. “Prosecutors are shocked, shocked, when someone comes in and wants to fight for his client in the old tradition as an adversary. Many defense lawyers don’t even know how to fight a case anymore. For twenty years I’ve been marching down to the prosecutor’s office to beg for mercy, and I’m sick of it. I can’t do it anymore.”

Laurie McPherson, who spent eight years as a defense attorney, concurs. “Very few criminal cases get to trial,” she says. “Everybody’s cooperating, and I got sick and tired of just writing sentencing memos.”

In the last criminal case she tried, McPherson says she represented a man in his sixties accused of distributing marijuana. “They never found so much as a seed directly connected to my client,” she remembers, “but the government brought in three thugs, convicted felons, to testify. As a result, my client got 27 years, a veritable life sentence.” The prosecutor, she adds, even asked for a longer sentence. “It’s tough, it really wears on you, and the rewards just aren’t there anymore.” McPherson has given up criminal law for the most part, concentrating on civil work.

Some of those who’ve stayed have become so uncomfortable representing cooperators that they’ve actually begun to refuse to do it. “I view my role as a criminal-defense lawyer as a buffer against the state and a watchdog on abuses by the prosecution, the police, and the judges,” says Diarmuid White, who’s been practicing nearly twenty years. “When you represent a cooperating defendant, you’re actually sitting down with the government and helping them make cases against other people, and I don’t think that’s good for our democracy. I won’t do it. I lose business, but I sleep well at night.”

Rudin argues that the pursuit of punishment at all cost has caused those in the system to lose sight of everything else: “Loyalty to friends, to family, is an important value. So what happens to the person who gets set up by some desperate informant who’ll say anything to save his own skin? Now that person is in the same position, being asked to give up friends, family, anybody to save themselves. The system acts like this is the highest virtue. And if someone has too much loyalty to do this, or simply doesn’t have anyone to give up anyway, the system will then destroy him. I really don’t want to be a part of that system any longer.”

Rudin is certainly not alone in his feelings. Among defense lawyers all over the country, the rumble of discontent has been growing louder for some time. Law journals and trade-association publications regularly carry articles by defense lawyers railing about the problems they face. These diatribes cover everything from serious legal issues (the erosion of a defendant’s rights and the enormous increase in the prosecutor’s power) to business problems (a shrinking client pool and smaller fees) to the increasingly degrading way they’re treated by the courts (since September 11, defense lawyers are no longer allowed to enter many courthouses through the same entrance as judges and prosecutors, which often means long waits to go through security). “We have been emasculated by the system,” says Hugh Mo.

“I’m angry, I’m frustrated, and I’m upset,” says Lawrence S. Goldman, president-elect of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “This has become a less pleasant profession, a less remunerative profession, and a profession in which it is far more difficult to be successful.”

“We went through a twenty-year war on crime and a twenty-year war on drugs,” says activist and lawyer Gerry Lefcourt. “And the result is what I call the Tyranny of Small Decisions. Everything has gone their way. From the appointment of conservative judges to the extraordinary budgets for every aspect of law enforcement, to the astonishing volume of criminal-justice legislation put forward every year by politicians frightened of being labeled soft on crime, each decision has pecked away at citizens’ rights and served to promulgate the multifaceted intimidation of the defense bar.”

Even the gregarious Murray Richman has lately taken a distinctly gloomy view. “I now tell young people not to go into criminal law,” says Richman, whose own daughter Stacey has been practicing with him for five years. “I tell them it’s a dead end, that there’s no future in the criminal-justice system for a young lawyer today. To me that’s truly, truly heartbreaking.”

Ron Kliegerman, who has spent the past 30 years as a lawyer and whose practice includes representation of the firefighters union, goes one step further. “If I had it to do all over again, I wouldn’t even go to law school.”

In fact, O.J. was an anomaly. The big trials that have captured the public imagination in the past decade, and vastly enriched their legal stars – think David Boies – have mostly involved corporate litigation and class-action lawsuits. Meanwhile, the cachet of criminal lawyers, once admired as the swaggering, cocky, self-absorbed risk takers of the legal profession, has plummeted.

“Between the abuse you take from your clients and the way you’re treated in the courts,” says defense attorney Richard Rosenberg, “a lot of us feel this business is dead now, that it’s over.”

“Because of what’s happened to our role in the system, nobody takes defense lawyers seriously,” says Richman. “We’re looked at as money-grubbing, mean-spirited people who are trying to screw the government and get guilty people off.”

Except, of course, by those people whose freedom is at stake. “No one speaks well of a criminal-defense attorney,” says Brafman, “until it’s their ass that’s in the hot seat. Then suddenly you’re the most important person in America.”

Before the mandatory guidelines went into effect, when someone was convicted at trial, there was still plenty of wiggle room when it came to sentencing because the judge would ultimately make the decision.

He could and usually did take all kinds of factors into account when sending someone to prison, from what kind of person they were to how much remorse they displayed to what, if any, unusual circumstances might have motivated them to commit the crime. Now the judge has virtually no discretionary power unless the prosecutor agrees to offer a letter of downward departure that frees him from the guidelines and says the defendant should get a reduced sentence.

“It’s a very unfortunate development that young prosecutors with little if any life experience are given enormous power to exercise,” says Brafman. “Part of my frustration is that not every criminal case involves a bad person doing something bad. Many times it involves a good person who’s done something bad, and those distinctions now get blurred in the system. I spend a substantial amount of my time and effort lobbying the prosecution on charging decisions because this is one of the most important moments in a case.”

The great irony here is that while the guidelines were adopted to eliminate disparity in punishment, they often produce exactly the opposite result, because dealmaking puts all the inequity back. If a defendant is willing to skip trial and plead guilty, the likelihood is the prosecution will offer him a reduced sentence. However, since these deals are usually proffered up front, right after arrest and indictment, taking an offer means the defendant sacrifices his right to file motions and even to learn what kind of evidence the prosecution has.

The defense lawyer is operating in the dark and essentially has to take the word of the prosecutor when he says he has the goods on a defendant.

Not surprisingly, U.S. Attorney Alan Vinegrad, who has successfully prosecuted such high-profile defendants as Justin Volpe and Charles Schwarz for the torture of Abner Louima, has a different view. “The sentencing guidelines have significantly changed the system,” he acknowledges, sitting in his Brooklyn office with its extraordinary view of lower Manhattan. “But the change has been positive. They’ve provided more meaningful sentences where it’s appropriate and a greater degree of consistency.”

Vinegrad, who fits the classic tough-but-fair description, points out that the guidelines are not a “straitjacket,” and in half the cases handled by his office, a lighter sentence than the one called for in the guidelines is imposed. And only a little less than a quarter of these reductions are a reward for cooperation.

“The U.S. attorney’s office has the top people in the legal profession, who work very hard for much less money than they could make in private practice,” he says. “And they are here to do justice. That means putting the bad guys away and not prosecuting the wrong people.”

Most citizens, of course, applaud the fact that the criminal-justice system has become tougher, less flexible, and more adept at locking people up for longer periods of time. And what difference does it make if a bunch of self-important, overpaid defense attorneys find their jobs more difficult and less satisfying?

“When you surrender liberty for security, you have neither security nor liberty,” says Richman. “I don’t mean to get on my high horse here, but we are liberty’s last champions. We have to keep the government honest. We have to hold them to a strict standard. We’re the rocks upon which the ocean breaks. After us is the deluge.”

There is, however, a simpler image to consider. “Once a year a neighbor or a friend or someone I know will come to me and say their son or their nephew or their co-worker got arrested,” says Diarmuid White. “And they will invariably say they can’t believe how they were treated. It’s always somebody who’s pro-police and pro-law-and-order – until it comes home and they see how things actually work. They’re always shocked.”

None of the lawyers I talked to had any reason to believe things would change anytime soon. “It’s actually gotten tougher,” says defense attorney Joe Tacopina. “Think about how it is since September 11. I walk into the courtroom and the proceedings begin. I stand and say, ‘Joseph Tacopina for the defense.’ And across the aisle, the prosecutor stands up and says, ‘So-and-so on behalf of the United States of America.’ Every person in the jury box is wearing a flag pin. And I think, Man, this is not going to be easy.”

Judge Weinstein, however, who takes a somewhat longer view, says penalties, particularly for first-time offenders, have already begun to come down. “All of our institutions are very complex,” he says, looking for a reason to be hopeful, “but ultimately pragmatism will prevail.”