I can relate to the Russian general defecting during the height of the Cold War,” says a partner at one of Manhattan’s biggest law firms. “Everyone knows which partners are likely candidates to leave the firm, and they watch you closer than the KGB, especially if you have a portable practice. They look at it as their money you’re taking with you when you leave.” He recalls how he was approached by his new firm after the legal press reported that he’d won a large chunk of business – a big securities offering by a Fortune 500 company. Over several weeks, the defecting partner met with key lawyers from the suitor firm during a series of clandestine lunches at different SoHo bistros – the kinds of places more often patronized by German models, disinherited counts, and hipster tourists than by Wall Street lawyers. Negotiations about compensation took place in the lobby bar of the Peninsula Hotel, the preliminary agreement sketched on the back of a cocktail napkin. “It was a little cloak-and-dagger,” he says, laughing. “We chose places where I was unlikely to run into anyone from my old firm. If anyone had found out before a deal was struck, it would have been worse than awkward. It would have been war.”

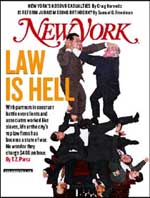

They’re wearing combat boots at the white-shoe law firms these days. Only ten years ago, news of a partner’s leaving his longtime firm had the shock value of an archbishop’s joining the rabbinate. People once hitched themselves to a firm for better or for worse. Today, big law is a fast and dirty profession, with impulsive Vegas-style firm-to-firm nuptials, rancorous partner divorces, and he-who-leaves-with-the-most-clients-wins game plans. A young partner at one big Manhattan firm tells of being threatened with bodily harm by an older partner when he tried to deal with a big client directly. “He was joking, but not really,” says the more junior esquire. “He made me swear that I would never meet with the client unless he was in the room.” A senior partner who recently left his longtime firm says the aggressive maneuvers pulled by his younger colleagues made him feel like grizzled Santiago from The Old Man and the Sea, dragging his marlin to shore: “You win a big client, and you can’t even finish one deal before other people are trying to tear a chunk off for themselves.”

Whatever happened to firm loyalty? The institutional pride that made these firms as prestigious as the Ivy League schools where they recruited? Whither the eminent consiglieri, the trusted advisers who had the ears of corporate titans and who for generations enjoyed a sense of leisurely superiority to their banking and business clients who spent their time chasing after the bucks?

“We made a Faustian pact,” says another partner. “In the eighties, business was so good that the partners got rich beyond their wildest dreams. The firms did anything to accommodate the flow of business – hired associates that they had to fire later, set aside traditions. We got used to big profits. As a result, we compromised our dignity and respect.”

“The day of the firm as family has passed,” admits Francis Morison, senior partner at Davis Polk & Wardwell. “As is the case with sports teams and Fortune 500 corporations, lawyers are now free agents.”

The most recent high-profile partner defections include Dennis Block, who left Weil, Gotshal & Manges for Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft last July, and Rigdon Boykin, the head of Chadbourne & Parke’s Hong Kong office and the heart of its international project-finance practice, who went over to O’Melveney & Myers in October.

Block and Boykin were just following the examples of lawyers like John Kirby Jr. – whose jump from Mudge Rose Guthrie Alexander & Ferdon to Latham & Watkins in 1995, while he was still the head of the firm’s executive committee, was widely regarded as the bullet that slayed Mudge Rose – and litigator David Boies, who quit Cravath (the firm nobody ever leaves) in 1997 to hang out his own shingle in Washington, D.C.

And those are just the marquee names. Hundreds of young rainmakers are now playing musical firms. Flip backward through the 1999 calendar: There are the five Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker litigation partners who skipped over to Proskauer Rose in May; an intellectual-property partner at Fish & Richardson who swam over to Rogers & Wells one month before; and the three partners from Anderson, Kill & Olick who hightailed it to Davis & Gilbert in March. Then there’s Ellen Werther, the Liz Taylor of law partnerships: Since 1993, she has been attached to at least three firms, including Coudert Brothers; Akin, Gump, Straus, Hauer & Feld; and Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy (which she left this year). Major defections in 1998 include the four partners from Milbank, who jumped to the New York office of U.K.-based Freshfields last September. A conga line of three partners, nine associates, four secretaries, and a paralegal at White & Case shuffled off to Linklaters & Paines, another English firm, last May.

Fierce salary scuffles are breaking out as the biggest firms attempt to lasso high-yield partners and the most competent associates. And though both associate salaries and partner profits have exploded over the past twenty years, surveys indicate that big-firm lawyers are less satisfied with their jobs than ever. An American Lawyer survey this month reports that 93 percent of all partners are pleased with their decision to practice at a large firm, but, as one recently made partner countered on the newly founded Yahoo! club Distressed Partners, “If I were unhappy … I still couldn’t see expressing my dissatisfaction, even anonymously, to The American Lawyer.”

“I must get twenty résumés from junior partners every week,” says Stephen Revell, head of Freshfields’s New York office. “They want out, a better deal, a surer future.”

This isn’t your father’s country club. Lawyers have started treating one another like, well, lawyers.

“Everyone fights over who gets credit for bringing in business,” says Marianne Rosenberg, a White & Case partner who jumped to the more collegial English megafirm Linklaters & Paines in May 1998. “Older partners shield their clients. Younger partners try to steal them.”

“Reamers and dreamers” is how one ex-associate who recently took a job as an investment banker classifies his colleagues of the past three years – the partners who mercilessly bombard associates with work and the associates who desperately yearn to escape as soon as a dent is made in the law-school loans.

“The partners scream at me, and I scream at the paralegals,” says one Sullivan & Cromwell associate. “And the paralegals scream at the word processors. I hope the word processors go home and scream at their dogs or something, because if not, we’re going to have a real postal situation on our hands.”

The dissatisfaction is plain on every level. Young law-school grads used to yoke themselves to the city’s big firms with the understanding that good work would lead them inevitably to the grail of partnership and the status that once went with it. (The author was an associate at Cleary, Gottleib, Steen & Hamilton from 1996 to 1997.) But today’s associate regards the firm as a mere stepping stone to investment banking, or an in-house job at a company that will treat him better. “For this I killed myself to get an A in constitutional law?” asks an associate at Davis Polk & Wardwell. “To pull three all-nighters a month chasing commas in a document and then get yelled at when a partner finds a typo I missed?

Partners smile with pride and point to their firms’ expanding ranks, new foreign offices, and mounting lucre. “Business is booming,” exclaims Stephen Volk, senior partner of the bulging-at-the-seams 725-lawyer firm Shearman & Sterling. “We’re doing great!” The bigger the better is the partner mantra these days – merger fever is spreading fast among the city’s firms, touched off by the recent announcement that the 1,990-lawyer English firm Clifford Chance stands to acquire the 128-year-old, 425-lawyer Manhattan-based Rogers & Wells in the coming months.

A merger between White & Case and Brown & Wood that would have resulted in the nation’s fourth-largest firm, with more than 1,200 lawyers, was scotched in March. But many more mergers are in the works, driven by the city firms’ desire to have an international presence and foreign firms’ seeking a beachhead in the world’s top financial center. Chadbourne & Parke is reportedly looking to join forces with a European powerhouse after a shaky couple of years marred by partner defections and slow-growing profits. England’s Freshfields has been sniffing around Milbank; Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson; and Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle is rumored to be deep into merger negotiations with the British law firm Norton Rose. “It’s a bit like elephants mating,” says Stephen Revell, the managing partner of Freshfields’s rapidly growing New York office. “But if the banks can do it and the insurance companies can do it, there is no reason the law firms can’t do it, too.”

Revell predicts that at least five midsize New York firms (150 to 250 lawyers) will disappear in 1999. Indeed, merger mania is driven by the fear that today’s large firms of 300 to 400 lawyers won’t be able to compete with the new global megafirms offering one-stop shopping for all legal needs across many jurisdictions. “There is a growing fear that everyone will rush to the church at once, and there won’t be enough brides,” says a Morgan, Lewis partner.

Today’s typical big Manhattan law firm is like a soaring skyscraper hastily constructed on the eighteenth-century foundation of a Beaux-Arts gentlemen’s club – and the stress fractures are showing. “It used to be the firm against the world. You really were brothers,” says an ex-Coudert Brothers partner. “Now you can’t trust anyone. You have lunch with a colleague, and the next week, he’s taken his clients to another firm. Watch your back, or the guy down the hall will try to have you kicked out because your billings are down that year. It’s every man for himself.”

Take superlawyer Dennis Block; Weil, Gotshal & Manges is still smarting from his defection. Block packed up his 24-karat corporate-law practice – reported to be more than $15 million in annual billings – and moved from Weil’s midtown office tower to 207-year-old Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft’s old-style Wall Street offices. The 56-year-old senior partner spent almost three decades at Weil, building an impressive roster of clients including General Electric and Bear Stearns.

Both of those companies’ general counsels have stated publicly that they will continue referring matters to Block. “Clients don’t hire law firms anymore – they hire lawyers,” Block says emphatically. “My clients didn’t select Weil; they selected Dennis Block, and most, if not all, of my old clients followed me to Cadwalader.”

Bad news for Weil, but deeply satisfying to Block, a small man with graying hair and a slight paunch who is wearing a rumpled maroon tie when we meet in his document-cluttered Maiden Lane office. He is soft-spoken until a call interrupts our early-morning chat. Then his tone becomes one of intense authority – impatience and control. “What the fuck is that?” he hisses, hunched over the phone. “That is the stupidest fucking thing I ever heard. Listen, goddammit, this is the way it’s going to happen …” It’s $500 an hour’s worth of legal lash, well spiced with profanity – and a Block signature.

Block claims he went to law school because he lacked the will to follow through on his undergraduate plans at suny Buffalo to be a dentist. He made his name advising the eighties’ most infamous corporate raiders – Carl Icahn, Ronald Perelman, and Sir James Goldsmith – on their hostile takeovers and later litigating on their behalf when the inevitable shareholder suits were filed.

Block says he often works from six thirty in the morning to ten at night, seven days a week, and says that not a Sunday dinner in 30 years has gone by that has not been interrupted by an urgent phone call. “I didn’t build Weil’s corporate practice,” he says, “by working shopkeeper hours.”

Most partners who leave their old firm announce their departures only after they have secretly negotiated a new job; the New York State Bar Association’s rules of ethics prohibit lawyers from trying to woo clients away from their old firms before they leave. But in the increasingly mercenary law-firm world, such niceties are seldom respected. Block announced his departure and then spent three months dangling his client list in front of a dozen of Manhattan’s largest firms, all as he continued to conduct business from Weil’s midtown offices. A manic phone campaign ensued, with Block and his ex-partners both calling the big-ticket clients to win them over to their respective sides. He shrugs off the hot glares and icy treatment he received from many of his old partners in his months of limbo. “If you’re not getting support at what you’re doing – and I never got support at Weil – if you’re feeling that everybody is sort of out for themselves trying to build their own little fiefdom, then the satisfaction … isn’t there.”

“They’ve been having a great time in Block’s department since Dennis left,” says Stephen Dannhauser, a member of Weil’s five-man executive committee. “It’s been great to see so many leaders emerge and really come into their own.” Dannhauser insists the firm’s business-and-securities department is having one of its best years ever – even without Block – and that many of Block’s clients, including Bear Stearns, continue to use the firm. “I personally cannot imagine leaving all the close professional, personal, and client relationships that I have built here,” says Dannhauser, who has spent almost 25 years at Weil. “But then again, Dennis is a very special person.”

It’s telling that Block finally settled on Cadwalader – a firm that is itself a case study in how many New York law firms have reinvented themselves. “It’s certainly not kinder and gentler, but they are doing what works,” says one retired big-firm partner who admires what Cadwalader has done. “They buy the best lawyers away from other firms. Those lawyers bring big clients. Those clients generate big fees.”

In 1994, a cabal of young Cadwalader partners won control of the firm’s management committee. Adopting an initiative with the Orwellian name of Project Rightsize, the committee managed to oust seventeen older partners – partners who were being paid far more than their practices were worth, it was felt. More than twenty associates were also pushed out. (To help recruit new associates and to stay competitive with other firms also out there fishing for the best people, Cadwalader is paying first-years who start this fall an unprecedented $114,500.) Dusty and outdated practice groups, such as utilities and ship finance, were shut down, and so was a Palm Beach office, as the firm shifted focus to high-margin businesses like counseling on mergers and acquisitions, IPOs, and corporate restructurings – sexy Dennis Block-type deals.

It was an ugly affair, by most reports, a night of long knives in an erstwhile chummy environment that underscored the priorities phased in at most big firms over the past ten years. “There is no more patience for lawyers not focused on profits,” says management-committee member Christopher White, one of the coup’s leaders. When he was being deposed in the course of one subsequent lawsuit, Jack Fritts, a former Cadwalader chairman who supported Project Rightsize, stated: “Life is not made up of love. It is made up of fear and greed and money.”

Today, Fritts laughs ruefully at his testimony but says he was explaining how other big New York firms would steal away Cadwalader’s most productive lawyers if things didn’t change. Fritts points to the fact that one of the ousted partners has returned to Cadwalader as special counsel (essentially, a senior lawyer drawing a fixed annual salary). Still, two ex-partners are supposed to be getting a total of more than $5 million after suing the firm for breach of the partnership agreement.

Fritts was right to have been worried – more than 1,100 of the city’s big-firm partners have defected over the past ten years. Mudge Rose Guthrie Alexander & Ferdon, the 126-year-old firm where Richard Nixon was a partner before he became president, was sunk by a slew of thirteen partners and twenty associates who walked away in 1995. In 1998, 127-lawyer Donovan, Leisure, Newtown & Irvine dissolved after most of the litigation department marched off to another firm. The partner defections were prompted by different factors – declining profits, dissension over a proposed merger, or power struggles over firm management. But they illustrate only that it takes the defection of a few key partners to deal a death blow to firms with hundreds of lawyers.

“Even a few partners leaving looks bad,” says Morison of Davis Polk, a firm that he maintains has suffered no partner defections. “Clients don’t like to think that their counsel is distracted by internal problems – they’ll send their work somewhere else.”

Firms tend to lose their cool over partner defections. “They throw their toys at the pram,” says one New York-based partner of an English law firm that has swiped more than ten American lawyers over the past few years. “It’s not Goodbye, Mr. Chips. They do not wish them well.”

Jonathan Rod remembers how some Milbank partners behaved when he announced his imminent departure late last year: “They yell at you about being disloyal, ungrateful. Some of the hostility is heartfelt, some tactical, to guilt you into staying,” he says. “Then when you are gone, they circle the wagons, send a notice around wishing you luck but saying that your contributions to the firm were minor and easily replaced.”

When Jonathan DuBois, a Coudert Brothers banking partner, announced he was leaving the firm to join Morgan, Lewis & Bockius after a power struggle with firm management in 1996, a Coudert source says, disgruntled partners immediately locked DuBois out of Coudert’s Grace Building offices. (DuBois had to return with a lawyer in tow and a temporary restraining order to remove his personal effects.)

DuBois had previously rankled Coudert leaders by opening merger discussions with San Francisco-based Pillsbury, Madison & Sutro without telling the management committee, one Coudert partner recalls. An ex-Coudert partner claims the new committee stalled for six months on pursuing the merger – some suspect because its members were afraid of losing their positions of power. By the time DuBois was officially appointed to investigate mergers, Coudert was thought to be too weak to be attractive to potential mates. “We missed our window,” one ex-Coudert partner laments. “We could have been a contender in New York.”

It’s like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” says one big-firm partner. “Everyone is so intent on getting the gold that it destroys the firm.” All but a handful of the city’s big firms have rushed to prevent a similar partner flight by replacing their century-old “lockstep” compensation plans (under which all partners of the same seniority receive the same share of profits, irrespective of how much business they bring in) with an “eat what you kill” policy, awarding bigger draws to the rainmakers. A single-minded focus on profitability guided firm policy, and if that meant firing dewy-eyed associates or exiling loyal old partners, then so be it. “Management by terror” is what Jon Lindsey, New York-based principal at legal recruiter Major, Hagen & Africa, calls it, noting that a firm in which all the partners and associates are just looking for the next better-paying job is not a firm that has very good long-term prospects.

The short-term benefits, however, are clear. Now it is Cadwalader that is skimming the cream off competing firms. Christopher White says that the firm has poached almost twenty new partners from other firms over the past five years. It is also luring top mid-level associates with some of the highest salaries in the market. Cadwalader is now a lean, mean billing machine, its per-partner profits as reported in The American Lawyer soaring from from a low of $425,000 in 1994 to more than $800,000 in 1998.

Like an NBA franchise bidding for a top forward, the hungry management at Cadwalader won Block (as well as two other Weil partners and six associates) by handing him partial control of the firm’s corporate and litigation departments and meeting his astronomical salary demands – more than $2 million a year plus substantial retirement benefits.

Block points out that he was the highest-paid lawyer at Weil and denies that money was the primary motivation for his move. But Weil sources disagree. They trace his disaffection to his claim that Weil’s foreign offices were hemorrhaging cash and sucking profits away from the firm’s New York headquarters. There was a power struggle with Weil patriarch Ira Millstein and the firm’s management committee, which Block describes as “Millstein’s brownnose lackeys.” Weil’s Dannhauser claims that the firm’s ten satellite offices are all profitable. Block insists that branch offices in places like Budapest, Warsaw, and Prague are useful only if they direct big clients to the New York office; branch offices require huge investments, Block says, and they aren’t worthwhile if they are going to generate only low-end, less-interesting, and less-profitable legal work. “Weil wants to have an office in every nook and cranny of the world,” Block snorts. “They want to do real estate in Hungary!”

“At some of these firms, you’re asking older partners to direct some of their profits to offices whose monetary benefits they may never receive,” Davis Polk’s Francis Morison explains. “The gloves come off, and they come off quicker than ever these days.”

In today’s law firm, there are the rainmakers, and there are the sponges, who absorb the work as best they can, producing thousands upon thousands of billable hours through a painful metabolic process involving eighteen-hour workdays, 24-hour word-processing departments, and piles of late-night delivery menus.

In the old days, it was those associates passed over for partnership who quietly booked passage to work in-house for the firm’s corporate clients. But increasingly, many young lawyers are fleeing to in-house legal departments that offer reasonable hours, great pay, and the long-term security that was once the hallmark of the big law firm. A 1998 survey done by Price-waterhouseCoopers’s Law Firm and Law Department Consulting Practice indicates that top in-house positions pay as much as the average partner earns at a top-50 law firm. “And you get options,” crows Michael Prior, an ex-Cleary, Gottlieb associate who is now in-house at a Seattle investment-advisory firm.

In the current big-firm factory atmosphere, it’s hardly surprising that mid-level associates are fleeing their firms in record numbers, even though they’ve never been paid more. The problem is so severe that the New York State Bar Association has a committee dedicated to issues of associate retention and quality of life. “People leave to run chocolate shops in Vermont or work at investment banks,” says one legal headhunter in Manhattan. “Some move to other firms, but many, many do not want to see the inside of a big law firm ever again.”

“Observe the drones in their cells,” says a senior associate as we wander late at night past rows of cramped fluorescent-lit offices at one midtown firm, each occupied by a grim-faced associate stoically digesting stacks of paper with his or her back to a spectacular view of Manhattan. “It’s quite a life. Do I need to mention that the windows don’t open?” In 1992, a Cleary, Gottlieb associate on leave of absence actually jumped to his death from the top of a building sometime after being released from a hospital where he was being treated for depression.

And law firms wonder why their most talented associates are leaving for the city’s investment banks. “Lots and lots of them want to go over,” says Toby Spitz, a legal recruiter in Manhattan. “They impress a managing director while doing a deal, and the next thing you know, they’re making three times as much as a banker on the other side of the table.”

Adding insult to injury, the bankers all but use their lawyers to polish their wing-tips. “I remember years ago seeing some very junior banker screaming at a very senior associate from a big law firm because the investment bank’s name wasn’t properly placed on a bond prospectus,” says a 41-year-old senior managing director at a major investment bank, laughing.

“There is something almost feminine about the work that the lawyers do – conforming documents and checking for typos,” his 28-year-old co-worker, a vice-president, snickers. “They tidy up and put everything in its place. The difference between banking and lawyering is the difference between hunting and weaving.”

Adds the managing director, “The big law firms are like standing armies, and you need that when you are trying to put a deal together quickly. But I’ve been in the Army, and it’s not much fun.”

Fifteen years ago, the legal-search business was virtually nonexistent in New York. But today, advertisements for dozens of legal-search firms crowd the backs of the trade papers, packed in tight beside tombstone notices announcing firms’ newly admitted partners. Headhunters stay busy playing both sides – promising associates deliverance from the chain gang and offering the firms fresh bodies to plug the gaping holes in their pyramid of lawyers.

“They start calling as you approach the end of your second year,” says Sascha Rand, a litigation associate who left Weil three weeks ago to study constitutional law at Oxford. “Everyone seems to leave after two years.”

“The headhunters euphemistically call these other firms they’re pitching you ‘lifestyle’ firms,” adds an associate at Davis Polk, who says they like to rattle off billable-hour stats – “2,200 at this firm versus 2,800 at the one you’re at.”

At the higher altitudes, firms develop hit lists of key partners who have expertise and clients in areas the acquiring firms want to build. The headhunters pore over The American Lawyer’s annual survey of the 100 most profitable firms – widely credited as a catalyst for all the firm-hopping – because firms with the slowest profit-per-partner growth are the best hunting grounds.

Ratcheting up the pressure at the megafirms is the fact that every time an associate migrates over to a client, the firm isn’t just losing another associate but gaining an auditor. “I feel no personal bond at all with Skadden,” says one lawyer of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, where he was an associate for almost five years; he now works in the legal department of a large manufacturing company as in-house counsel. “I occasionally use them,” he says. “But I don’t let them get away with the kind of stuff that I got away with.” Corporations are increasingly motivating their in-house lawyers by paying bonuses for cost-cutting.

“There is much more scrutiny of bills than there was before,” affirms Stephen Volk at Shearman & Sterling. A booming legal-audit industry has been feeding on a steady diet of fatty firm bills and growing client suspicion since the early nineties. As partners try to transform almost every part of a firm’s infrastructure into a profit center, including the word-processing, fax, and photocopying departments, law firms became ripe auditing targets. “It isn’t just the 50-cent photocopies, $2-a-page faxes or $500 meeting-room snack plates that really drive up costs,” says Judith Bronsther, a principal at Manhattan-based Accountability Services, Inc. “Law firms aren’t dishonest, but they have purposefully selected practices that tend to maximize profits and not efficiency – the billable hour being the clearest example.”

Legal auditors raise their eyebrows high at such recent tactics as paying associates bonuses based on billable hours. Since the salaries and overhead of associates are fixed, every dollar of fees generated through billable hours by an associate that exceeds the costs to keep him becomes profit for the partners. “It’s an invitation to fraud,” says Bronsther. Yearly billing targets that five years ago were aspirational are now mandatory at many firms, according to Bronsther; time sheets are kept even at such firms as Cravath and Sullivan & Cromwell that say billable hours do not directly determine how much a client pays or associate compensation.

What does it mean for an associate to bill 2,500 to 3,000 hours a year? It means billing more than ten hours a day, assuming the standard four-week vacation and weekends are sacred. However, most complain that working at least one day on the weekend is expected. Many also admit a tendency to overstate the number of hours worked.

As one third-year associate who billed 2,900 hours in 1998 explains: “If I am at the firm for fifteen hours, I bill for all fifteen, even though I may only work twelve or so after personal phone calls, lunch, whatever. You feel justified if you are there until midnight every night on a deal – it’s sad, but my biggest sense of progress at the firm is watching the hours build up on the billing-status reports that the firm sends me every month.”

“The big-firm practice breeds freaks!” shouts one associate who recently crossed over to the investment-banking side. “Look at the kind of person you have to be to put in the time to make partner,” says an ex-Cleary associate. “These are people who put their heads down in high school and never picked them up again.”

Associates cynically refer to themselves as billing units, but partners maintain that bonuses are dispensed out of fairness, to ensure that all associates pull their weight. “There have to be incentives,” says Cadwalader’s Christopher White, whose firm paid up to $32,500 apiece last year to associates who billed more than 2,500 hours. “Clients have been demanding more and more from us, and you can’t ask associates to give up so much without spreading the wealth.”

And the firms need to stay competitive, especially with all the newcomers sharp-elbowing their way to the table. Roughly 100 out-of-town U.S. firms have opened New York branches. The five principal U.K. firms – Clifford Chance; Linklaters & Paines; Freshfields; Allen & Overy; and Slaughter and May (the Magic Circle, as they are known in England) – are gunning for IPOs and bond issues and are agreeing to cap their fees, a practice that is giving their Manhattan counterparts night sweats. Although technically restricted from practicing law by the New York State Bar Association, the Big Five accounting firms are also worming their way into the gray area of tax consulting; each currently employs more tax attorneys than most big New York firms.

Firms have suddenly found themselves in the position of having to convince company CFOs that they can do the best job at the lowest price. “For many years, there was very little competition for clients,” says Charles O’Neill, the operations partner at Chadbourne & Parke, who joined the firm in 1972. “You weren’t always hustling for business. Partners spent very little time managing and a lot of time practicing law. Now you have to consider competition, management techniques, marketing, and long-term planning. You have to keep more balls in the air these days.”

Recruiting is one of them, since associate bodies equal more billable hours, which equal more profits. Reports have the 500-lawyer Coudert Brothers panning for legal talent as far away as New Zealand, and many big firms have been browsing at top Canadian law schools. For the past ten years, first-year-associate classes at Manhattan’s most prestigious law firms have been ballooning. That means some hapless Debevoise & Plimpton junior partner with an affinity for grits flies to Atlanta and checks into the Westin to participate in Emory Law School’s recruiting day. Emory is ranked No. 28 in U.S. News & World Report’s 1999 “Best Law Schools” survey, but that doesn’t mean that a good number of the top ten New York firms won’t be battling to lure the school’s top students.

With its 1999 first-year class numbering 143, Skadden is recruiting at 43 law schools. The partners make light of school rankings today and argue that getting top grades just about anywhere is a fair signifier of professional promise. B students at Fordham are suddenly finding they have the leverage of The Firm’s Mitch McDeere; they command signing bonuses and salaries that topped $100,000 in 1998.

All this confounds the partners, especially the older ones, for whom being elected to the firm was something akin to being knighted. The vets are secretly aghast at some of the oddballs who have dropped into their midst. There was the Davis Polk associate who is said to have shaved his eyebrows; people also believed he was sleeping under his desk. Some at Skadden still remember the summer associate who arrived at a firm dinner in jeans and a T-shirt that read I FUCKING LOVE NEW YORK CITY.

“I don’t give a damn about race or religion,” a senior partner at a big firm tells me over drinks at the Yale Club. “Smart, cultured people – who cares where they pray? It’s not the diversity that’s the problem, it’s – what? It’s hygiene. It’s taste.

“You should see some of these kids,” he continues. “I had an interview lunch with one a month or so ago. You should have seen him attack his food – like an animal. He did everything but bang on the table with his knife and fork to get the waiter’s attention. And all the time talking and chewing with his mouth open – I swear, I didn’t hear a word he said the whole meal.”

He stares into space for a moment. “Twenty years ago, that would have been it – you couldn’t have a client see something like that,” he says, shaking his head. “But this kid was smart and a hard worker, evidently. So we took him.”

Client contact is now rare for young lawyers at the vast majority of firms. Nor is a partner likely to find himself mentoring this associate at close range. “I used to spend most of my time working directly with one partner for a single big client – that’s how you learned,” says Jack Fritts, who joined Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft in 1959 as part of a five-man associate class (Cadwalader’s 1999 class comprises more than 60 associates).

“Cravath is sink-or-swim,” complains one associate. “They don’t want to hear your questions. There’s no formal or informal training. They want you to be a Green Beret – go into a situation and blow things up like Rambo.”

“It was a much more social and friendly atmosphere before,” says another large-firm partner. “There were a lot of good old functioning alcoholics back then – the three-martini lunch really happened. You’d go out and get all the gossip and then come back and work. Unfortunately, the nature of the work doesn’t allow that anymore.”

“The partners have gotten caught up in all the extra pressure to be more and more productive, and probably have forgotten how important it is to make associates feel they are part of the firm,” Stephen Volk admits. “I think associates don’t recognize that it is not impossible to become partner.”

Only one in every ten associates eligible for partnership at Manhattan’s biggest firms is elected, according to the New York Law Journal. They wait between eight and twelve years to cross the threshold – longer than ever before, even if it’s true that more associates are making partner in the aggregate. But with partners in their mid-sixties pulling back-to-back all-nighters these days, making partner is certainly looking less and less attractive.

As is an associate position, which has become an ongoing negotiation at Manhattan’s big firms: An associate will break rocks in the hot sun, but his sweat now goes to the highest bidder. If the partners are astonished by this approach to the venerable profession, they shouldn’t be – at Manhattan’s big law firms, greed flows downhill.

“They’re just imitating the partners,” says Bradford Hildebrandt, president of Hildebrandt International, a law-firm consultant. “They see the partners leaving or fighting for more money, and they do the same.”

It is no coincidence that firms announce staff bonuses in October and November, around the time that most students are culling their summer offers. And the associates manipulate the process, too: In September of last year, Manhattan associates received anonymous e-mails announcing huge boom-year bonuses at several large firms, including Skadden, Cravath, and Simpson Thacher & Bartlett. Panic rippled through the firms that didn’t give such high bonuses as disgruntled associates forwarded the e-mails – containing bogus information, as it turned out – on to partners. A compensation war ensued, and big firms revised their bonuses upward with each new announcement. Cravath and Willkie Farr & Gallagher reportedly prevailed, with special minimum bonuses of $15,000 for associates and special counsel.

Firms are coming up with all kinds of silver seat belts to keep the help: In January, Shearman & Sterling announced that it would pay an estimated $50,000 bonus to each associate after the completion of his or her third year and an additional $50,000 to associates whose chances to make partner or counsel are deemed good after their sixth year.

“Feeding the monkeys,” says a senior partner at one of Manhattan’s most prestigious firms, laughing. “Every year, they rattle the cage a little louder. I wish I had known that you could complain like that back when I was an associate. I would have rattled the cage, too. But, you know, it just wasn’t done.”

It’s a changed culture. Among the rank and file, ancient white-shoe folkways are the subject of endless ridicule. “There are a few of the old guys still around wearing bow ties and leaving the first button on their suit sleeves unbuttoned to show that they are the real deal,” says one big-firm associate. “There’s this one guy who is always saying I should come to his club to play squash, and I’m like, You have to be kidding me. I’m this kid from Staten Island. The pinkie rings and the white hair, you know – nice guys, but you want to shake them and say: ‘Hey, listen – I’ve been here for three days straight, and I smell terrible.’ There’s nothing clean and noble about this stuff. It’s down and dirty, like Uncle Lou’s retail. It’s business, baby, so let’s not pretend.”