At 4:30 on a Tuesday afternoon, I stood on the south side of Montague Street in Brooklyn watching the Social Security offices, waiting for Dennis to come out. I wasn’t sure what he looked like. I had a number of photographs of him at age 24, a thickly built blond guy with thinning hair and broad heavy planes in an intelligent face. Bearded, introverted. But what use were the pictures? They were from 1976. Dennis had lately turned 50.

Having gotten a primer from a private-eye friend about tailing people, I followed a few fiftyish Dennises down the street. None of them seemed right. Then it got to be 5:20 and I was heading home myself when a man came out of the office door and everyone else on the rush-hour block seemed to vanish. Most of his hair was now gone, but the beard was still there, and so was the inward intensity, the determined anonymity. Dennis’s oddball spirit was so distinct and strong that it had passed unchanged from the old pictures I carried. He wore jeans and a T-shirt, carried a knapsack, wore photogray glasses, as he had worn jeans and a T-shirt and carried a knapsack and worn photogray glasses 26 years before, on the night that Deb in one of her last acts had knocked his glasses off, breaking them. He had left them in the blood on the floor of her hut, got on his bike, bicycled off into the darkness.

He looked like what he had been then: a Peace Corps volunteer. I followed him down the street and into the subway, then lost him.

I’d first heard of Dennis more than 25 years ago. In 1978, I was 22 and backpacking around the world when I’d crashed with a Peace Corps volunteer in Samoa named Bruce McKenzie. He said that a year or so back in the Kingdom of Tonga, a tiny island nation in a crook of the date line, a male Peace Corps volunteer had killed a female volunteer. There had been some kind of triangle. He was a spurned or jealous lover. He had stabbed her many times. The American government had moved heaven and earth to get him out of Tonga. Bruce didn’t know any names, but he said the case had caused considerable friction between the Peace Corps and Pacific-island governments, and hearing this by the light of a kerosene lamp, with the heavy rain clattering on the roof, I formed a romantic idea of a story out of Maugham or Conrad, of something terribly wrong that had unfolded in an out-of-the-way place. A true idea, as things would turn out.

I returned to the story several times in the intervening years, learning the killer’s name, Dennis Priven, and something of the government machinations that had given him his freedom. It became an occasional obsession, something that nagged at me all my adult life.

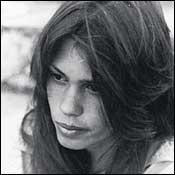

The victim’s name was Deborah Gardner. She was 23, a natural girl in a seventies way, with a laid-back, Pacific Northwest vibe. In Tonga, in 1976, she rode her bicycle everywhere by herself at night even when people told her she shouldn’t, she didn’t wear makeup, she put her thick dark hair up in a rubber band at night and took it down in the morning, washed her clothes by stamping on them barefoot in a basin with a Jethro Tull tape going. She decorated her one-room hut with tapa cloth and native weavings, and lay on her bed all afternoon reading Heinlein or Hesse.

Her hut was on the outskirts of Nuku’alofa, Tonga’s capital city, alongside the home of a gangling, humorous Californian named Emile Hons, who was friendly with Dennis. Deb taught science and home economics at the leading educational institution in the country, Tonga High School.

“He must have spent $100 on this dinner,” Deb said. “Doesn’t he know I don’t want to go out with him?”

People said she was the prettiest girl in the Peace Corps.

She dressed modestly, in denim skirts and men’s button-down shirts, but men still noticed her big laugh and the way her body moved. There were 70 other volunteers in the country, and sometimes it seemed like every guy in the capital wanted to go out with her. She had dated two New Yorkers, ethnic exotics to her own western-mixed Lutheran background; and then a third New Yorker had wanted to date her, too.

She was polite to Dennis Priven. He lived a mile or so away from her and taught chemistry and math at the leading Methodist high school. Most volunteers were wary of him. He was the best poker player on the island, and took everyone’s money, and they did not understand why he didn’t look anyone in the eye and carried a large Seahorse dive knife with him everywhere.

Still, he had a few close friends, drawn to him by his humor and intelligence. “[He] succeeds at what he wishes to do,” volunteer Barbara Williams wrote home about Dennis. “Since he has a beard & usually wears cut-off blue jeans, the Tongans think he’s sloppy—which he isn’t. Keeps his desk, bookshelves, home very nearly neat as a pin. The students are scared of him, not knowing that beneath that gruff exterior lies a tender heart of the sort that rescues fair damsels in distress. He’d hate to think so, though, disliking sentimentality. All in all he’s too good to waste—I keep wanting to match him up with some fluffy little wisp of a girl with a will of iron. They’d live happily ever after.”

Dennis pined for the voluptuous girl with the Kelty backpack from Washington State. One night, he awkwardly invited Deb to come over to his house for dinner, and she accepted. His friends helped him put the meal together. Emile thought of it as a high-school gambit, and other friends of Dennis also saw the date in high-school terms. Perhaps implicit in the planning was a judgment of Deb—Dennis was a serious soul, Deb was a party person. He’d be good for her.

The dinner went badly. Dennis had high expectations and had gotten Deb a gift, spending real money. He was full of awkward feeling, and the situation became unpleasant. She ran out of his house, got on her bicycle, rode into the night.

When Deb saw a former boyfriend, Frank Bevacqua, later, she was upset. “He must have spent $100 on this dinner. Doesn’t he know I don’t want to go out with him?”

“You have to tell him that.”

Over the next few months, Dennis’s thoughts about Deb became more sinister. It upset him that she skinny-dipped in violation of tapu, or taboo (the word is originally Tongan), and did not thank him enough after he had put in a sink for her. She found it impossible to escape him. He came to her school on his bike every day to visit, even after her vice-principal had told him that he was not welcome there. And though his behavior—the knife he always carried, some bizarre and menacing statements—drew the official attention of the small Peace Corps staff, he somehow managed to hang on into the last months of his two-year service.

In part to escape him, Deb applied for a transfer to another island. Then in October 1976, the Peace Corps held a dance for a new group of volunteers, and that night seemed to unhinge Dennis. Deb got drunk, and fell twice on the dance floor, and then Emile took her home, accompanied her into her hut.

Five nights later, Dennis arrived there himself. He had his dive knife with him, and also a syringe, a metal pipe, and two jars containing cyanide. Later his friends would learn that he intended a surgical murder, in which he would club Deb with the pipe and make her unconscious, then destroy her. But Deb started fighting him, fending off his knife with her hands, leaving horrible wounds; ultimately, Dennis stabbed her 22 times. Her Tongan neighbors discovered him dragging her out the front door. He jumped on his bicycle and fled into the dark, and the neighbors brought her to the hospital in the back of an old green truck. Doctors worked valiantly, but the damage to her aorta and carotid artery was so severe she would have died if Vaiola Hospital had been the Mayo Clinic.

Dennis’s plan called for him to kill himself, as he told friends later, but he changed his mind about that part. At midnight, he bicycled to the house of a friend, Paul Boucher, and the two of them went to the police station. Why have you come here? asked the Tongan detectives. I have tried to kill myself, he said. He had taken an overdose of Darvon, and feebly cut his wrists.

“Do you know Miss Deborah Gardner?” asked Chief Inspector Faka’ilo Penitani.

“No.”

“Was she a friend of yours?”

“I have nothing to say.”

“It appeared to me that all pity was with Priven and none was shown to the dead girl,” said the Tongan prosecutor. “I find this very strange justice.”

Two days later, Emile brought Deb’s body home to the United States. Deb’s parents were divorced, her mother living in Tacoma, her father in Anchorage. They came together at the funeral for the first time in years, and though they were disturbed when a Peace Corps official said that the government would have to pay for Dennis’s defense, they accepted the policy.

Dennis had done it; he was locked up, and was going to be for a long time.

In the weeks to come, the Peace Corps threw itself completely behind Dennis. A volunteer was in a primitive jail, facing hanging. The future of the Tongan program was at risk. The woman’s shell-shocked parents did not show up in country, and no one in the United States knew about the case. The Peace Corps was careful to keep it that way. Even when it reported the case to Vice-President Nelson Rockefeller so that he could send condolence letters to the Gardners, the message was oblique. “She died shortly after her arrival at the hospital.” Nothing about a murder. And though policy called for immediate announcement of volunteer deaths, the Peace Corps waited nineteen days, till November 2, 1976, the day of the presidential election, Carter over Ford. The story was buried.

Over the next three months, the Peace Corps did all it could to make the nightmare in Tonga go away. It brought in Tonga’s most famous lawyer from New Zealand to represent him. It summoned a psychiatrist from Hawaii who testified that Dennis was a paranoid schizophrenic. Dr. Kosta Stojanovich’s words were translated into Tongan as “double-minded” for a jury of seven Tongan farmers, none of whom had graduated from high school.

There was no counter-expert. There wasn’t a psychiatrist in all the kingdom, and the Tongan government could not afford to bring one in. And though the prosecution tried to demonstrate that the murder grew out of a jealous triangle, Peace Corps witnesses proved elusive on this score. Even Emile said that his relationship with Deb was “brother-sister.” The jury went out for 26 minutes before rendering an insanity verdict, and Crown solicitor Tevita Tupou complained bitterly to the king: “It appeared to me that all pity was with Priven and none was shown to the dead girl. The Peace Corps effort may have been made to try and save the name of the movement from the embarrassment of one of their members being convicted of murder. I find this very strange justice if this was the case.”

The worst was yet to come. The Tongan police minister was for keeping Dennis at the Tongan prison farm. But the king and other members of the Cabinet deferred to the Americans. The State Department gave a letter to the prime minister promising that Dennis would be hospitalized involuntarily in Washington till he was no longer a danger to himself or others, and that if he made any effort to escape his fate, he would be arrested. These were misrepresentations. Sibley, the hospital the State Department cited, only accepted voluntary commitments, and when he got back to Washington in January 1977, Dennis refused to go in. Peace Corps lawyers then desperately called the Washington police, who said that they had no power to arrest Dennis.

At last, under pressure from the Peace Corps, his parents, and the two friends who had brought him back, Dennis agreed to see a psychiatrist at Sibley. Zigmond Lebensohn reached an opposite conclusion to Stojanovich’s back in Tonga. Dennis wasn’t psychotic, he was shy and sexually inexperienced and had suffered a “situational psychosis.” He had been led on by a pretty girl who then slammed the door. “For this kind of guy, that triggered everything. Everything went kaflooey,” Lebensohn later told me. He could not commit him. After the case ended in 1977, a story went out among teachers and doctors and policemen and schoolchildren back in Tonga: Dennis Priven was dead. He stepped off the plane in the United States, and someone from the girl’s family, her uncle or brother, came up and shot him on the tarmac. The story went around like wildfire. People wanted to believe it. The story satisfied a deep social understanding, that if somebody killed someone, it would catch up with him, he would die.

But Dennis didn’t die. He was free. He went home, moved into his parents’ co-op in Sheepshead Bay. He got a clean discharge from the Peace Corps—Completion of Service—and a month later applied for a new passport, and reportedly got it. He rejoined his Brooklyn College fraternity poker game, though the frat brothers joked that you should keep sharp objects away from him. Once, a group of buddies confronted him about Tonga—Did that really happen? Dennis shrugged. He said it had happened, it was a long story.

His family came apart. Miriam, his sickly mother, died a year after his return. Sidney, his printer father, moved to Florida with a new wife.

Dennis and his older brother, Jay, a coach at Boys and Girls High, stopped speaking. He was the eternal Peace Corps volunteer. He wore his beard heavy and rode his bicycle everywhere. He didn’t look people in the eye.

He married a Hispanic woman in the early nineties. By 1996, he was divorced, still living in the apartment he had grown up in. He worked at Social Security, as a top computer manager: area systems coordinator. He made $78,000 a year.

I’d spent years thinking about Dennis, even dreaming about him. It had become more than a writing project—one that I’d started several times over the decades. It was something approaching a mission. Deb Gardner was alive in me, in a sense. I was surprised at how much anger I felt over the injustice done to her by Priven and her own government. In the late nineties, I’d taken the story up in earnest, going to Tonga several times. And finally, toward the end of my reporting, I approached him. I wrote him a letter, saying I was writing a book about the events in Tonga in 1976 and wanted his help. A few days later, I was standing outside the Sheepshead Bay subway station, trying to chart his movements, when I got a call on my cell phone. It was Dennis; he wanted to meet me. “This will be short,” he said.

Workmen were eviscerating Broadway at Prince. The jackhammers were going, girls walked by in their slip dresses. From the coffee bar at the front of Dean & DeLuca, I saw a girl whose lace underwear showed above her wrap skirt and thought about how these women would have seemed to the kids in Deb’s Peace Corps group, Tonga 16, with their long dresses to wear in a conservative, Christian society.

I’d spent years preparing to meet Dennis. In my knapsack I had documents from New Zealand, the analyses the government had done for the Tongans on Deb and Dennis’s clothing 26 years before. I wanted to be ready if he said he was innocent.

Dennis arrived promptly at noon. He was the man I’d seen in Brooklyn a few days before, with dark glasses and a fixed, lowered, oxlike expression.

We shook hands, and Dean & DeLuca suddenly felt tight as a closet. He gave a tilt of his head, and we went out.

“Do you go by the standard journalistic ethics?” he said, turning onto Prince.

“Yes, why?”

“So … everything I tell you is going to be off the record.”

“Okay.”

And I interpreted that in the strictest way. “Everything I tell you.” Not anything he asked me, or showed me.

We spent the afternoon together. As we talked, we walked up and down lower Manhattan, sticking to the big avenues. In some ways he was the most important person in the story, and I didn’t understand who he was.

There were two theories about him. One was the anybody-can-snap theory that an old colleague of his, Gay Roberts, had told me in New Zealand. In his second year in Tonga, Dennis was isolated and unhappy, and one bad thing after another had happened, till he’d snapped, Gay said—it might happen to anyone. Then there was the evil-genius theory that the Tongan police minister, ‘Akau’ola, and Deb’s former boyfriend Frank Bevacqua, subscribed to. Dennis was a poker player. He’d planned this to a fare-thee-well, playing lawyers and governments and shrinks off each other.

Dennis walked beside me, now and then giving the faintest smile. The same untelling mug that people had watched during his nine-day trial. He stared straight ahead through dark-brown Armani glasses, but now and then I got a glimpse of his eyes: deep-set, dark, big, liquid holes. I couldn’t say what he was thinking, though when I told him the Gay Roberts theory he went to a plate-glass window and traced a big circle on it with his finger and then stuck his finger in the middle of the circle.

His beard was shaved neatly around his mouth and cheeks, but his shoulders in a cutoff Champion T-shirt were hairy, and he had a funny walk in his jeans shorts. His manner was so sensitive that it sometimes seemed feminine. There was that tenderness Barbara Williams had seen. Now and then he reached out and grabbed me, to stop me from walking into traffic, and the sense his friends had had in Tonga, that he would do anything for you, was mine. A couple of times he stopped me in a brotherly way to tug the zipper up on my knapsack. It was his mind that was most interesting. It was strange, and it could go anywhere. And he was funny.

When we hit Union Square, he pulled out a folded piece of paper and read me a proposal. He said I could convey his terms to my editors, so I will report its fuzzy outline here: Dennis had no interest in my book coming out, but if I waited a few years to publish he would tell me everything.

I should have anticipated such a gambit. Emile had described to me a chilling visit to Dennis in jail after the murder when Dennis had unfolded a grand double-jeopardy scheme in which Emile would come forward at the last minute of the trial and take the rap, freeing Dennis— after which Dennis would come forward during Emile’s trial. In this way, Dennis had theorized, they would both go free.

What I told Dennis was that he should come forward because of the havoc the case had left in the minds of a hundred or so people who knew about it, the idea that a person could kill someone and walk away from it. I reminded him of what Tongans had said to him many times, that he must apologize to the girl’s family and ask their forgiveness. I reminded him of the scene in Crime and Punishment where Raskolnikov confesses to Sonya the prostitute and says, What should I do? and Sonya says, Go to the crossroads and kiss the ground in four directions and say I have sinned, and God will give you life again.

It was my own form of bluff. The Gardners didn’t want to talk to Dennis. If Dennis went to Deborah’s mother in Idaho on bended knee, Wayne would know what to do with him and it wasn’t listen. Wayne wanted Dennis imprisoned, or hanged back in Tonga. He wanted justice.

I didn’t tell Dennis that. What was his idea of justice, anyway? I’d learned that he was too interior a person to believe in justice, his imagination too crazy and elaborate. He lacked any superego. This was just some misunderstanding that had happened between a couple of people. “She deserved it,” he had said in Tonga, and maybe he still believed that, and in that sense he seemed to me evil. He had treated the murder and his release as a form of accomplishment, not something to be regretted.

He’d maintained a poker face for three months in Tonga. He had almost killed himself with hunger strikes two or three times so as to be kept in the jail in downtown Nuku’alofa, near his friends, rather than at the isolated prison farm. And while Emile had refused to play the double-jeopardy game, other friends had helped him. He’d made a kind of confession to Barbara Williams, in order to gain admission back into the human family, but Barbara’s loving expectation that he would be incarcerated in a mental hospital meant nothing to him. Another friend had given him a Bible that he had read thoroughly in jail, and he had then told Dr. Stojanovich that he was Deb’s Jesus Christ and savior and she was possessed by the devil—or he had allowed Stojanovich to say as much on the stand. Then, in the States, Dennis had told Dr. Lebensohn that Deb had led him on and crushed him. Two different stories, each the key to its respective legal doorway.

Believing it pointless to cite a larger social good, I appealed to Dennis’s grandiosity. I said that what he had pulled off was actually a stunning addition to the annals of crime. There was a brilliance to it, a negative brilliance, for sure, but most surprisingly, the story was unsung. I was going to change that; didn’t he want to help?

“Okay, if I’m as smart as you say I am, then how come it’s not me with the big house by the lake in Seattle?”

“You’re as smart as Bill Gates, you just care about different things,” I said.

I’d pictured this encounter for years, and always with explosive scenes. He did get angry a couple of times, and I had the underlying sense that he was deeply dissociated, but all in all it was a civilized meeting. He was a free man in Soho. We were two middle-aged cerebral New Yorkers, lost in conversation, tied together by intense feelings about a beautiful loner of a woman whom he had prevented from ever growing old, and whose crystalline girlhood had trapped me, too, in seventies amber.

We went back to Dean & DeLuca. I got a bottle of juice and he got a lemonade, and we walked south. “I want to show you my pictures,” I said.

We sat on a rusted iron stoop on Grand Street and I showed him 100 or so of the images I’d collected. He flipped impassively through the pictures of Deb, broke down when he saw a picture of his old friend Paul Boucher, lost it for a few minutes, had to walk off down the street. The narcissistic monster, only thinking about his own bloody life.

Then he carefully drew something from his knapsack he’d brought along, a stiff card with a blue edge, his membership in the Royal Nuku’alofa Martini Club, a group founded by expatriates in 1975. It was an artifact from before Deborah, before his life had fallen apart.

In the months that followed our meeting, Dennis was to quit his job at Social Security and change his phone number again. Having gotten away with murder 28 years ago, he was condemned to preserve that terrible achievement. He was still on his bicycle, rushing into the dark forever. He could put the thing away in a box, but the box never went away. For the time being, though, Dennis put away his card, and I put away my pictures of Deb. We got our knapsacks on, had a moment’s small talk, then he headed toward Broadway, I headed toward Lafayette. He didn’t look back, I’m sure of that, but then neither did I.

Adapted from American Taboo, by Philip Weiss, forthcoming in June from HarperCollins.