It takes a toll on the imagination to place Haron Amin in Afghanistan’s Panshir Valley in 1988. Now 32, Amin seems too young, too sophisticated, too comfortable in his natty suits and Hermès ties – too American, really – to have fought alongside the mujaheddin and suffered the depredations of a brutal war. “They had to drag me through a couple of the passes,” Amin recalls of his first weeks with the rebels. “I fell terribly ill, the food was meager, and the eighteen-hour marches were devastating.” * What was a 19-year-old Afghan-American doing in the Panshir? At a time when more than 6 million Afghans were fleeing their country and taking refuge in squalid Iranian and Pakistani camps, Amin was swimming against the stream. He dropped out of college to become the only Afghan in America to go fight with the mujaheddin, spending two years alongside Ahmed Shah Massoud, the legendary Northern Alliance commander who was assassinated on September 9.

“It was my Islamic duty,” says Amin of his decision to return to the country he had left with his parents in 1980, bringing with him vivid memories of the morning in Kabul in 1978 when his third-grade geography teacher came to class carrying a Kalashnikov. A few days later, the kindergartners in his cousin’s class were ordered to report their fathers for engaging in political activity or hiding guns in their homes. His parents endorsed his call to arms. “If a family has more than one son, one son is supposed to be given for jihad – so my parents had no argument. It also was an issue of patriotism.”

Thirteen years later, Amin does battle on another, very different front for the Northern Alliance. Until recently, as the Alliance’s envoy to the United Nations, Amin had trouble getting meetings with U.N. aides. “There wasn’t a single ear to give us even five minutes,” he says, “and if they did, it was followed by a yawn.” But since being named the Alliance’s Washington envoy in early October, Amin is in such hot demand in D.C. that he hasn’t set eyes on his Queens home. The U.S. hopes the Northern Alliance’s 30,000 ground troops will eventually topple the Taliban. “Without us on the ground,” Amin says with a touch of bravado, “the U.S. would have almost no chance of capturing bin Laden.”

For the city’s roughly 20,000 Afghan-Americans, the world could not be more radically different from the way it was before September 11. They have gone from obscurity to suspicion if not outright harassment. Their quiet despair for relatives back home has bloomed into pungent fear. But they’ve also risen from a hopeless stupor over the fate of their country to feverish politicking – even to dreaming of victory.

Just three hours after the first American missiles hurtled into Kabul on October 7, nearly 200 Afghan-Americans gathered in an emotional summit at the Mustang Café in Fresh Meadows, Queens, to bring unity to a fragmented Afghan diaspora and to create an agenda to help guide a new government. Western diplomats hope that moderate members of the Taliban will join the Northern Alliance in backing the restoration of 87-year-old King Zaher Shah, living in exile in Rome since 1973.

But optimism about their homeland is tempered with a fear for their immediate safety here. To many Americans, Afghans are the enemy by blurry association – “Osama bin Laden,” “Taliban,” and “Afghan” became virtually synonymous after the attacks. Afghan-Americans have stopped wearing turbans and head scarves. “On campus, Muslim girls had their shawls ripped off their heads,” says Rasa Hashimi, 19, a sophomore at suny Stony Brook attending an Afghan peace rally in Flushing on a sodden October Saturday. Both Afghan mosques in the neighborhood have been under continuous police protection since September 11.

Amin, for one, won’t reveal where precisely he lives in Queens. “I don’t want to be hunted down,” he says. “I’ve received several death threats.”

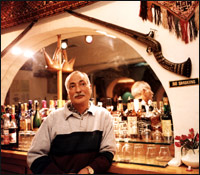

“The first two weeks, my friend, I tell you it was un-be-liev-a-ble,” recalls Shah Rohani, the owner of Bamiyan, an Afghan restaurant on 26th Street and Third Avenue. “People were writing graffiti in the window. No one would come in – no one. I was thinking, I’m Afghan, I must be a criminal.” As recently as last week, death threats had followed Rohani to his New Jersey home, where he now patrols his house at night carrying a kitchen knife.

A lifetime ago, Rohani, now 55, was a supreme-court justice in Kabul, the top graduate in his law-school class. When the Soviets came, he fled to New York, where, after a two-year stint as a busboy, he opened Caffé Kabul at 32 St. Marks Place. “Americans loved Afghanistan back then,” he says. And it wasn’t just the food. Over the next decade, the U.S. would send $3 billion and its best CIA operatives to help the Afghans undermine the Soviets specifically, and communism generally. If history was ending, the Afghans were the exclamation point.

Habib Mayar pulls out a stack of photographs – here he is sharing jelly beans at the White House with Ronald Reagan, there’s Senator Alfonse D’Amato embracing him at a Plaza fund-raiser. Throughout the eighties, Mayar, the 63-year-old owner of a landscaping business on Long Island, was the de facto mayor of Flushing’s Little Afghanistan. As founder of the Afghan Community in America, he helped refugees secure political asylum and find jobs. “We were heroes,” he recalls wistfully in the gravy-thick Afghan accent he hasn’t shaken, “the great freedom fighters, slaying the Soviet monster!”

Amin remembers a night in 1986 when, as a teenage volunteer, he took several injured mujaheddin who had been evacuated from Afghanistan to a San Diego hospital for treatment. At a checkpoint near the Mexican border, their car was stopped and they were whisked to the commanding officer. “The moment he looked at us, he got very mad. ‘Why did you stop these men?’ he scolded the guard. ‘These are the brave Afghan fighters combating the Soviets!’ I was so incredibly proud!”

Now, suddenly, their country has been subsumed under America’s arch-nemesis. As a result, almost every Afghan-American has become, at least publicly, a fierce foe of the Taliban regime. Even the Taliban’s official envoy to America shrinks from naming allies. “Please do not trust me to find someone who is pro-Taliban,” implores Abdul Hakeem Mujahid, 45, who has gone underground somewhere on Long Island. “I might find an enemy and say he is pro-Taliban – please do not trust me!”

The first thing Afghan-Americans tell you today – passionately – is that they denounce the World Trade Center attacks and Osama bin Laden, and that Afghans have never engaged in terrorism. “There is not a single Afghan accused in any way in any international terrorist incident,” says Barnett Rubin, senior fellow at the Center on International Cooperation at New York University. “Even during the Soviet occupation, there was not a single act of violence against any Soviet target outside Afghanistan.”

They are also quick to note that Afghans are not Arabs – in fact, Osama bin Laden and the thousands of Middle Easterners who came to fight the Soviets in the eighties are known derisively as “Afghan Arabs.”

Until 1989, the city’s Afghan-Americans did not dwell on their ethnic differences. They had all been raised in the relatively tolerant, multicultural Afghanistan of King Zaher, who ruled the country for 40 years until he was deposed in 1973. Religion didn’t divide them, either. “Every Afghan political group wants an Islamic government,” Rubin says. And after 1979, Afghans were too focused on vanquishing the Soviets to bicker among themselves.

The Afghans who came to America were more secular than those who stayed behind. “They were more educated, and many had been to the West,” says M. Hassan Kakar, the author of a book on Afghan resistance to the Soviets who spent five years in a Kabul jail before coming to the U.S. “Also, they weren’t on good terms with many of the radical mujaheddin, who were trying to establish a theocracy. Those who came here, generally speaking, believed in democracy and elections.”

Curiously, these relatively secular Afghans became more conservative after coming to America. “About the only thing people took refuge in in the eighties was religion – it was the force that united us with the Christian and Jewish worlds,” says Amin, who’s finishing his master’s in political science at St. John’s. “It was deeply rooted in the battle against atheistic communism. We had nothing to fight against the Soviets with except our religion and our Afghan sense of independence. Then, when we won, it reinforced the belief that religion was the answer to everything, since it had beat the communists.”

New York’s Afghans busied themselves building businesses – by 1984, they owned more than 200 fried-chicken shops (the secret’s in the red pepper and fresh garlic); later, they cornered the pushcart coffee-and-bagel business (they now have 800 stations in the city). Together, they erected two mosques in Queens, one an imposing million-dollar structure with a turquoise-and-white dome that recalls the Turkish Aegean. But they still considered themselves refugees, not immigrants – most planned to return to their country once it was no longer a battleground.

That moment came in 1989 with the Soviet withdrawal, but in no time it disappeared. Civil war engulfed Afghanistan, and the West, busy designing the New World Order, turned its back. “We were abandoned,” Amin says. “You don’t invest $3 billion, then pull out, and not expect things to go wrong.” Amin, who returned for two years to Kabul in 1995 to work with Massoud, blames ignorance and foreign intervention for the instability that followed.

“You know what? You could say the mujaheddin sucked at governing,” he says bluntly. But Amin says the mujaheddin might have survived had Pakistan, which desperately wanted a subservient Afghanistan, not backed the Taliban. “Pakistan chose a new pawn. They had it cooked up and we didn’t know about it – we thought the Pakis were on our side.”

The fault lines began to show in New York too. “Ethnic divisions got steadily worse among the exile groups from 1989 on,” says Rubin. The Sayed Jamal-ud-din mosque, in a shabby mint-colored clapboard house on Beech Avenue, became identified with the Taliban, who are mostly Pashtuns. The grander Masjid Hazrat-I-Abubakr Sadiq mosque on 33rd Avenue attracted more of the non-Pashtuns. The tribes still mingled, but less so. Almost no one went back to Afghanistan.

Seven years later, the Taliban swept through the country with their fundamentalist creed. “Everyone was exhausted by 1996,” Rohani says. “Afghans were very poor and very tired; there had been so much raping and criminality. The Taliban came and everyone was happy – or at least they were relieved to think about religion rather than war.” The Taliban took away people’s guns and restored a sense of calm to the streets.

In New York, too, Afghans were encouraged – roughly half of them now say that they supported the Taliban in 1996. Dr. Bashir Zikria, chairman of the Afghan National Islamic Council and one of the king’s closest advisers, remembers throwing a garden party for the Taliban’s foreign minister in 1996 at his Norwood, New Jersey, home. “They were very open-minded and told us they were coming to establish calm and security,” recalls Zikria, a professor at Columbia Medical School. “They answered every question to our satisfaction.” Perhaps this time the peace would stick.

It didn’t. Soon, women were banned from work, the amputated limbs of convicted thieves were hung from trees, and adulterers were stoned in a Kabul stadium. Like Amin, many Afghan-Americans say outsiders manipulated the Taliban, who, failing to muster the West’s support, turned to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, whose punishing Wahhabi interpretation of the Koran they adopted. Nor did it help that the Taliban were ignorant of the world and unable to cope with modernity.

“When they first arrived in Kabul,” says Prince Mostapha Zaher, the king’s grandson, who is known as Moose, “they thought it was the most sophisticated city in the world – even though it was a complete ruin by then. They didn’t know better.” It might have been different had the U.S. backed the Taliban. “America abandoned us again, brother,” Mayar says.

To help heal the post-1989 ethnic rift, Zikria convened the October 7 meeting at the Mustang Café under the auspices of ANIC. It just so happened the American assault began on that day, making the unprecedented event even more fraught. With representatives from all the major Afghan communities on the East Coast present, Zikria hoped to elect a representative counsel to advise the king. It was the biggest political meeting in memory.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the wealth and education they’ve accumulated here, Afghan-Americans are being courted assiduously. Zikria is one of five on the king’s 33-member decision-making council. Prince Mostapha, who lives in Rome, says he has spoken to dozens of young Afghan-Americans in New York and that they were all enthusiastic about returning, at least temporarily.

“We are preparing an agenda for the king, so that we can convene a loya jirga in Afghanistan by the end of the year,” says Zikria, referring to Afghanistan’s traditional deliberative body.

“This was the first time they actively sought out women to participate,” says Masuda Sultan, founder of Young Afghan World Alliance. She and others say that Afghan men became more liberal after September 11, championing women’s rights as a way to distance themselves from the Kabul regime. Younger Afghans were especially energized. “The older generation is always fighting,” complains Rameen Javid Moshref, 32, founder of the magazine Afghan Communicator. “The younger generation wants its own voice.”

When it has one, it will play a crucial role, because it is the younger generation that can best reconcile the West and Islam. “Being born there, growing up here, we have a lot of cultural values that our parents taught us that didn’t translate easily into ordinary life here,” says Moshref, who wrote his NYU thesis on the Taliban. “We’ve had to work hard to make the two worlds work.”

“We should concentrate on being American and understanding the system we have here,” says Ramin Rasuli, 22, a politics major at Columbia. “The Shariah law is very similar to America’s democracy – it might not be the Electoral College, but it’s the same principle. And Islamic laws are the most just laws you can find.”

None of the younger set are under any illusions about what is possible for now in Afghanistan. “You can’t have feminism if you don’t have food,” Sultan says. “Women’s rights have a place, but the most important thing is that people live. Religion gets thrown on the back burner. Culture gets thrown on the back burner.” Sultan wants the first event of her new organization to be a fund-raiser to benefit both fallen firefighters and Afghan refugees. It is her way of linking two tragedies that she seems to feel equally.

“You know what? You could say the mujaheddin sucked at governing,” he says bluntly. But Amin says the mujaheddin might have survived had Pakistan, which desperately wanted a subservient Afghanistan, not backed the Taliban. “Pakistan chose a new pawn. They had it cooked up and we didn’t know about it – we thought the Pakis were on our side.”

The fault lines began to show in New York too. “Ethnic divisions got steadily worse among the exile groups from 1989 on,” says Rubin. The Sayed Jamal-ud-din mosque, in a shabby mint-colored clapboard house on Beech Avenue, became identified with the Taliban, who are mostly Pashtuns. The grander Masjid Hazrat-I-Abubakr Sadiq mosque on 33rd Avenue attracted more of the non-Pashtuns. The tribes still mingled, but less so. Almost no one went back to Afghanistan.

Seven years later, the Taliban swept through the country with their fundamentalist creed. “Everyone was exhausted by 1996,” Rohani says. “Afghans were very poor and very tired; there had been so much raping and criminality. The Taliban came and everyone was happy – or at least they were relieved to think about religion rather than war.” The Taliban took away people’s guns and restored a sense of calm to the streets.

In New York, too, Afghans were encouraged – roughly half of them now say that they supported the Taliban in 1996. Dr. Bashir Zikria, chairman of the Afghan National Islamic Council and one of the king’s closest advisers, remembers throwing a garden party for the Taliban’s foreign minister in 1996 at his Norwood, New Jersey, home. “They were very open-minded and told us they were coming to establish calm and security,” recalls Zikria, a professor at Columbia Medical School. “They answered every question to our satisfaction.” Perhaps this time the peace would stick.

It didn’t. Soon, women were banned from work, the amputated limbs of convicted thieves were hung from trees, and adulterers were stoned in a Kabul stadium. Like Amin, many Afghan-Americans say outsiders manipulated the Taliban, who, failing to muster the West’s support, turned to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, whose punishing Wahhabi interpretation of the Koran they adopted. Nor did it help that the Taliban were ignorant of the world and unable to cope with modernity.

“When they first arrived in Kabul,” says Prince Mostapha Zaher, the king’s grandson, who is known as Moose, “they thought it was the most sophisticated city in the world – even though it was a complete ruin by then. They didn’t know better.” It might have been different had the U.S. backed the Taliban. “America abandoned us again, brother,” Mayar says.

To help heal the post-1989 ethnic rift, Zikria convened the October 7 meeting at the Mustang Café under the auspices of ANIC. It just so happened the American assault began on that day, making the unprecedented event even more fraught. With representatives from all the major Afghan communities on the East Coast present, Zikria hoped to elect a representative counsel to advise the king. It was the biggest political meeting in memory.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the wealth and education they’ve accumulated here, Afghan-Americans are being courted assiduously. Zikria is one of five on the king’s 33-member decision-making council. Prince Mostapha, who lives in Rome, says he has spoken to dozens of young Afghan-Americans in New York and that they were all enthusiastic about returning, at least temporarily.

“We are preparing an agenda for the king, so that we can convene a loya jirga in Afghanistan by the end of the year,” says Zikria, referring to Afghanistan’s traditional deliberative body.

“This was the first time they actively sought out women to participate,” says Masuda Sultan, founder of Young Afghan World Alliance. She and others say that Afghan men became more liberal after September 11, championing women’s rights as a way to distance themselves from the Kabul regime. Younger Afghans were especially energized. “The older generation is always fighting,” complains Rameen Javid Moshref, 32, founder of the magazine Afghan Communicator. “The younger generation wants its own voice.”

When it has one, it will play a crucial role, because it is the younger generation that can best reconcile the West and Islam. “Being born there, growing up here, we have a lot of cultural values that our parents taught us that didn’t translate easily into ordinary life here,” says Moshref, who wrote his NYU thesis on the Taliban. “We’ve had to work hard to make the two worlds work.”

“We should concentrate on being American and understanding the system we have here,” says Ramin Rasuli, 22, a politics major at Columbia. “The Shariah law is very similar to America’s democracy – it might not be the Electoral College, but it’s the same principle. And Islamic laws are the most just laws you can find.”

None of the younger set are under any illusions about what is possible for now in Afghanistan. “You can’t have feminism if you don’t have food,” Sultan says. “Women’s rights have a place, but the most important thing is that people live. Religion gets thrown on the back burner. Culture gets thrown on the back burner.” Sultan wants the first event of her new organization to be a fund-raiser to benefit both fallen firefighters and Afghan refugees. It is her way of linking two tragedies that she seems to feel equally.