Three weeks before he took his own life, Allen Myerson, a New York Times business editor, and his wife, Carol Cropper-Myerson, a writer for Business Week, went out to dinner with their close friends Kevin Buckley and Karen Wirtshafter. A celebration was in order. That afternoon, last July 31, the Myersons had closed on their dream house, a $645,000 Georgian on the leafiest block in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. Kevin and Karen, both surgeons and neighbors in nearby Montclair, took them to the area’s nicest restaurant, Liberté. Champagne was uncorked, but Carol, despite being “positively bubbly” all night, barely took a sip. Her friends remarked that that wasn’t like her—Allen and Carol fancied themselves wine connoisseurs—and Carol blushed. “Well,” she said in her sweet Kentucky accent, “we have some other news as well. I’m pregnant!”

Kevin and Karen were delighted. Like most of the Myersons’ friends, they knew the five-year hell of fertility treatments the couple, both 47, had gone through in their attempt to conceive. On July 5, they’d tried one last time, and, miraculously, it took.

“You must be thrilled,” said Karen. Carol was, but Allen seemed oddly subdued. Usually he was almost manically upbeat, but tonight, as his pretty wife gushed on, he picked at his Chilean sea bass. Later, on the way out to the parking lot, the wives were walking ahead, and Kevin Buckley turned to his friend. “Allen, you’re a little quiet,” he said.

“That’s because I’m getting a divorce,” Allen replied.

The next day, Carol met her husband at the Times after work. They often joined friends for dinner, or took in a show, before returning to New Jersey. That night, they had tickets to a Mets-Astros game at Shea. “On the drive home,” says Carol, “he said, ‘I filed for divorce today.’ ” Carol Myerson was one month pregnant, with twins. In four days, the movers were coming to deliver the couple’s furnishings to their new home, but only she would move in. And 21 days from the night of the baseball game, Allen would stand up at his desk, make his way to a window near the top of the Times Square building, and plunge fifteen stories to his death.

To most who knew him, Allen Myerson’s suicide was unfathomable. He was the guy always in control, the consummate pro, the one who could handle any pressure, any deadline. Simultaneous breaking Enron stories? Get Allen. WorldCom imploding? Allen was your man. He was the Times editor who calmly weathered reporters’ freak-outs, never yelling, never losing his grip.

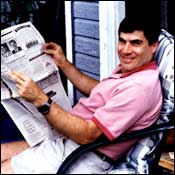

“Except for the competitive part, he was the opposite of the newsroom mentality,” one colleague says. Most knew the basic bio: a Jewish only son who came from modest roots in New Rochelle, went to Harvard, then worked his way through eleven years of newspaper jobs around the country before landing, in 1989, at the pinnacle, the New York Times. They knew he had a beautiful wife he was enchanted with, if a bit cowed by. And he seemed to have an unusually full life outside the newsroom. He didn’t just love the opera and the theater; his wallet was filled with membership cards to every company at Lincoln Center. He was a zealous foodie who took enormous pride in his familiarity with New York restaurants; friends were always impressed when the owner fawned over him. He had a book club and a rigorous gym schedule; he collected wines and was known for his adventurous travels—Turkey, China, Ireland, Indonesia, Italy—always with his wife. Depression? Despair? Not a hint.

Yet the man who never let on that there was any private drama in his world would, in death, have the most intimate details of his life and his psyche aired—by his own family. Not his Times family, as then–executive editor Howell Raines referred to his charges in his eulogy for Allen. But by his sisters, who are embroiled in a breathtakingly aggressive and unprecedented lawsuit against Carol Myerson over Allen’s estate. They hold Carol—who on St. Patrick’s Day in March gave birth to Allen’s twin children, a boy and a girl—responsible for his suicide. So rancorous is the fight that Allen’s widow secretly traveled hundreds of miles from Glen Ridge to deliver the twins, fearful that Allen’s sisters would show up in the hospital nursery.

Indeed, Jean Myerson—a 43-year-old Westchester housewife who bears an uncanny physical resemblance to her brother—began to assemble a suit against her sister-in-law within hours of Allen’s death. She hired a lawyer and a private eye and also became her own self-appointed investigative reporter, wheedling information out of banks, shrinks, even fertility clinics. She cashed in her IRAs and went into debt to finance her mission. She even ordered up a batch of buttons inscribed JUSTICE FOR ALLEN and began handing them out.

By September, when the Times held a memorial service for Allen, efforts had to be made to keep the sisters and the wife separated. As several hundred Times employees filed out of the teary service, Jean exclaimed, “I can’t believe that murderer is here!” Carol had to be escorted out a side door.

Nine months later, they are still fighting over his estate—about $150,000 in probatable assets—though the two sides combined have already plowed through more than that amount in legal fees. But the sisters also feel they deserve a share of the non-probate estate (which would normally go unchallenged to a spouse) as well; it includes Allen’s $100,000 Times life-insurance policy naming Carol as the beneficiary, his $230,000 Times 401(k), the proceeds from the sale of the dream house, and the couple’s car, worth $2,000.

They are also battling over the twins: Jean wants a paternity test, even as she claims that Allen was “tricked” into donating his sperm for the last in vitro treatment. They’ve fought over the menorah Allen got when he was 5, the $441 in cash he had in his wallet, and who will get his Harvard diploma.

Mostly, however, they are at war to assign blame.

To hear Jean Myerson tell it, Carol “tortured and abused” her brother, literally driving him over the edge. Unbeknownst to Carol, Allen had been spilling his guts to Jean in his final weeks, describing, she says, a manipulative and conniving wife who had “a carefully calculated plot” to get what she wanted—a house and babies, with “him footing the bill”—and still get rid of him. Jean also is armed with the eerie words of a dead man, in piles of personal notes and documents that Allen left behind or shared with her during the couple’s recent and seemingly inexplicable separation. Many of the notes, however, are confusing in their anguish and clearly contradictory—except to Jean. “I know exactly what she did to him,” she says, barely containing a seething rage.

To hear Carol Myerson tell it (though she tells it reluctantly), she is a woman in grief over her husband’s shocking suicide who now has two babies who will also have to live with that legacy. In Carol’s eyes, the Myersons—never very fond of her to begin with—are out to destroy her and the children.

Thursday, August 22, the morning Allen jumped, was a hot but gorgeous day. Since filing for divorce, he had been moving boxloads of personal things from his apartment to his desk—credit-card files, medical records, his marriage license, clothing, bottles of wine, and opera tickets through July 10 of the coming season. On that day, he got to his desk on the third floor at the Times by 8 a.m., earlier than usual. At precisely the same time, according to bank records, Carol was at the downtown branch of Chase Manhattan bank withdrawing $37,000 from their joint checking account, leaving a balance of $1,071. No one in the newsroom had an inkling that Allen’s marriage was on the rocks, let alone that he was about to become a father.

At 8:30, he received what seemed to colleagues to be a disturbing phone call. But he also went about his business; at one point, he asked reporter Steve Lohr, who covers technology, how his story was coming. To Lohr—and everyone else—he seemed perfectly normal. Shortly before nine, Allen sent his last e-mail, to Bill Pinzler, a lawyer who was trying to help him find an apartment in Manhattan—though Pinzler was still somewhat mystified as to why the couple was splitting up. In the e-mail, Allen wrote that he had just found out that someone else got the place Pinzler had tried to score for him on the Upper West Side; concerned about his finances, Allen had put in a lowball offer. “But he didn’t seem terribly upset,” says Pinzler. “It was more like, ‘Aw, shit, somebody else got the apartment.’ ”

Pinzler e-mailed back to say, “No big deal, we’ll find you another one,” but it’s unclear whether Allen ever read the reply. Between 8:52 and 9:04, he called Chase Manhattan four times. During one of those calls, he managed to transfer the final $1,071 from the joint checking account to his own. Then, at 9:06, he left a message on the answering machine of his divorce attorney, saying he needed to speak to her immediately, that it was an “emergency.” But he didn’t elaborate. By the time she called him back, minutes later, he had already left his desk.

Also that morning, he mailed his sister Jean a draft of a brutal divorce document, outlining a vicious litany of complaints about his wife. He was supposed to file it with the court that afternoon. Jean would later use it as the blueprint for her case against Carol.

At about 9:10, he received another phone call, his last. This one seemed to upset him even more than the 8:30 call (which Pinzler believes had been news about the apartment). Witnesses in the newsroom say he angrily slammed down the phone, with such force that papers went flying off his desk.

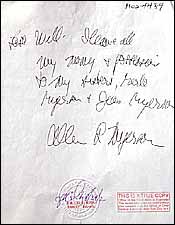

Then he scribbled a note, the validity of which is now a thorny legal issue: “Last Will—I leave all my money and possessions to my sisters, Merle Myerson and Jean Myerson.” Signed, “Allen R. Myerson.” He left his wallet and wedding band beside it.

Then he stood up and headed for the fifteenth floor.

That morning, Jean Myerson had taken her three children—a 5-year-old and 2-year-old twins—to the Botanical Gardens in the Bronx. They were on the tram ride when her cell phone rang: It was Merle, a cardiologist in Cooperstown, New York, at the time. “Allen’s been hurt,” she said. While still on the ride, Jean called one of his editors. “Jean, your brother’s dead,” he told her.

Natalie Myerson, who last saw her son the previous Saturday at her 79th-birthday party, at Jean’s house, was at the synagogue volunteering. Carol was at her desk at Business Week when her editor summoned her into his office. With him were two top editors from the Times. “I was saying hello to them and shaking their hands,” Carol recalls, “and they told me to sit down … ”

In one of the more curious subplots of this saga, it’s apparent from numerous documents that while Allen knew his wife was pregnant, he did not know that Carol had conceived twins.

‘You murderer!” Jean Myerson yelled into the phone at her sister-in-law, Carol, in their first conversation hours after Allen’s death. “You did this to him! You killed him.” Ten months later, this conversation is the only thing Carol and Jean agree upon.

“I don’t have to listen to this,” said Carol, hanging up the phone.

In another conversation that day, Natalie told Carol, “You’re not going to keep me from my grandchild.” Carol seemed surprised that she knew about the pregnancy. In one of the more curious subplots of this saga, it’s apparent from numerous documents left by Allen, as well as from conversations he had in the days before his death, that while he knew his wife was pregnant, he did not know, as Carol knew, that she had conceived twins. (Carol, despite numerous requests, declined to comment on this particular mystery.) Jean believes “she was holding that out for some kind of slam-dunk leverage.” And she wonders: Was that what he learned in that last phone call?

Allen’s corpse remained in the city morgue as the fight between his wife and his family quickly escalated. For nearly five days, they battled over his body, preventing him from being buried within 24 hours, as Jewish law requires. Carol, believing that as his widow, she had the right to bury him, chose a plot for her husband in a bucolic cemetery on a hill in New Jersey. Gravediggers dug the hole. But back in New Rochelle, the Myersons had already ordered another grave dug. Furious that Carol—whom they saw not as “the bereaved widow” but rather as the estranged, soon-to-be ex-wife—planned to bury him in a nondenominational cemetery, they threatened to file emergency motions to keep the body from Carol’s possession. They wanted Allen buried near his father, at a Jewish cemetery in Queens, even though that meant Carol, as a non-Jew, couldn’t ever be buried beside him.

Separate memorial services—“the dueling funerals,” as Allen’s pals at the Times put it—were planned, one by the Myersons, one by Carol. Plus, of course, a third, held at the Times auditorium. The bad blood put Times executives in an awkward position—and resulted in Raines and his colleagues delivering their eulogies three times.

On Sunday, August 25, three days after Allen’s death, Jean went with a friend to the spot where Allen had landed—on the roof of a parking garage—then to the morgue. She asked the attendant to leave her alone with her brother. She swore over the cold body that she would avenge Allen’s death. Then she took out a scissors and clipped a lock of his hair—”I was desperate for DNA evidence,” she said later—as she already planned to contest the paternity of the twins.

The next day, Carol presided over a service for Allen: prayers and eulogies at a Jewish funeral home, sprinkled with happy photographs of the two of them together frolicking in France and Germany. Her request to have Allen’s body present in a closed coffin was successfully fought by the sisters, who were convinced she would “pull a fast one” and bury him in the grave she’d had dug.

After the service, friends of Allen and Carol’s gathered for a catered luncheon at the precious Glen Ridge home that Allen never did move into and that Carol would soon put back on the market. Later, the $3,000 bill from Carol’s caterer (and the bill from her gravedigger) would be hotly contested by Jean, as his estate—now handled by a court-appointed administrator—began to try to pay all the funeral bills. Numerous Times people recall their discomfort at the luncheon: Why wasn’t Allen’s family here? Were the rumors all true? Could it be that the babies weren’t his? That Carol was having an affair? That she told him he’d never see the children? That she stole all his money?

That Monday, in another Jewish funeral home, in New Rochelle, Carol and her lawyers were in one room while Jean and hers were in another. The Myersons had just held their memorial service, which was dutifully attended by the crew from the Times. Later, as the rest of the family sat shivah with Raines, publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr., and the rest of Allen’s colleagues over soda and cold cuts at Natalie’s home (the Myersons’ submission to the estate was a grocery bill for $380), Carol and Jean were still duking it out over the body. Jean refused to budge on burying Allen in the family plot.

“My mother said, ‘Give her the body, just give her the body.’ And I said, ‘No, Ma. She took everything from him. She took his belongings, she took his money, she took his life. I will be damned if I’m gonna let her have his body!’ ” And there were other matters that had to be sorted out. Carol wanted her husband buried in a suit; the Myersons wanted Allen wrapped in a simple shroud, in accordance with Jewish tradition. Carol wanted a pricey coffin; the Myersons wanted a plain pine box, also in accordance with tradition. Carol, Jean says, wanted to ride in the family limousine to the graveside. (“I had to tell her,” Jean adds, “we don’t do limos. We drive ourselves.”) In the end, “Carol gave up,” say her friends, though she did get the casket she requested.

On August 28, Allen Reuben Myerson was laid to rest at Mount Judah cemetery in Queens, a bleak expanse of gravestones off the highway with broken beer bottles and trash strewn about. The Myersons (family, friends, cousins) stood on one side of the grave while Carol stood on the other, alone but for her brother, a Protestant minister who had married them fifteen years before. At one point, the rabbi himself took pity on her, handing her the shovel, as is the custom, so she, too, could throw dirt on her husband.

Allen and Carol met in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1981, when both were 25 and cub reporters at the Lexington Herald. Carol was a “sweet, pleasant local girl,” born and raised in Maysville, Kentucky. “And Allen was this fast-talking kid who’d gone to Harvard,” remembers Philip Terzian, an editor there. “Very ambitious and aggressive, among all these easygoing Kentuckians. We used to laugh about what the Myerson household must think of Carol, because they came from such disparate worlds.”

What the Myersons thought wasn’t pleasant. Carol says part of the reason she and Allen waited six years to marry was because his Orthodox parents were so opposed to the idea. That, and his ambivalence even then about having children. Jean admits that her parents were distraught over the possibility of a “mixed-race marriage,” as she calls it. “But Allen was smitten.” His mother would be the one to make peace: “My husband said, ‘I’m not going to that wedding.’ And I said, ‘Yes, you are. This is our son.’ ”

Through the course of their marriage, the couple moved continually as Allen worked his way toward the New York Times. He’d worshiped the newspaper since childhood, his mother remembers, adding that even as a boy he’d insisted on having his own subscription.

Allen grew up as a somewhat sickly child, terribly asthmatic but so determined to be like the other kids that he threw himself into sports, eventually running both the Boston and New York marathons. He wanted desperately, friends say, to impress his father, Sam, a civil engineer who was in and out of jobs and, by most accounts, was a difficult man. Some think he, too, secretly battled depression. In Carol’s court papers, she describes Allen’s family as “abusive and dysfunctional”—a characterization that incensed Natalie and the sisters. “His biggest fear was becoming like his father,” Carol says, “repeating his father’s life and their marriage. And this played out in all his mixed feelings, about buying a house, about having children.”

“Now you can see what a cruel bitch she is,” Jean retorts. “If we were all so mental, why was she so hell-bent on using his sperm?”

For many years, they put off having children because Allen “was never ready,” Carol says. But around the time they turned 40, Allen acquiesced to her desire to seek fertility treatments. At the time, they were living in Dallas, where Allen had landed the job of bureau chief for the Times—after paying his dues for four years on the Times copy desk back in New York. By all accounts, his years in Dallas, from 1994 to ’99, were his happiest. He loved his job, which allowed him to travel the state and write stories about quirky Texas characters who fascinated the kid from New Rochelle, without having to deal with the politics and daily grind of the newsroom. He had a tight group of close friends, and he and Carol became known for the shindigs they threw at their comfortable Dallas home—Kentucky Derby parties, catered barbecues, and the like.

But the party was over in 1999, when Raines’s predecessor, Joe Lelyveld, brought Allen back to New York and a desk job. Officially, being named “assistant Sunday business editor” was a promotion, and Allen, the consummate company man, did not let on to friends how crushed he was. He wanted to write more, not less; being chained to the business desk on the weekends wasn’t part of the big life plan. “He hoped his next step would be to become an international correspondent,” says Carol. “That was his dream.”

Around the time of the move back to New York, says Carol, their marriage began to hit the rocks. She blamed this on several things besides his new job description. With her income uncertain, they moved into a $1,000-a-month rental apartment in Montclair—too small to entertain the way they used to and an enormous step down in their standard of living. But more stressful was the fertility project. The endless, expensive rounds of unsuccessful procedures are, of course, a known marriage killer, exacerbated by the constant hormone treatments—and Allen’s continued waffling.

By January 2002, they were in regular marital-therapy sessions—in addition to several shrinks Allen saw. But they decided to pursue adoption. Allen, in what had become a recurring pattern, wavered between gung-ho participation (hiring an adoption lawyer, researching the laws in various countries) and resistance. Carol grew increasingly frustrated, says one of the couple’s friends, Cynthia Coulson. “She desperately wanted a child, and she only had so much time left,” says Coulson, who had explored the adoption route herself. “But then Allen decided he did not want to proceed with adoption.” By March 2002, five months before his death, they were back on the fertility track again. Both felt a sense of desperation—but for very different reasons.

The last months of Allen’s life were, like Allen himself, fraught with ambivalence. By late spring, he started telling his mother that he didn’t want to go through with the purchase of the big, expensive house. “Then don’t do it, Allen,” she told him. Later, he told her he didn’t want to donate his sperm on July 5. “Then why did you?” asked an exasperated Natalie. “Because she told me ‘I owed her,’ ” her son replied. “He told me the reason he needed the divorce,” says Jean, “was that he couldn’t stand the criticism anymore. That she blamed him for everything, including not being able to get pregnant.”

Still, that April, he squired Carol to the Champagne vineyards of France and the opera in Berlin. In early June, they headed to Cambridge for Allen’s twenty-fifth Harvard reunion. The occasion was something that had consumed Allen for months. He headed three different reunion committees and, with Carol at his side, attended nearly every event of the long weekend, though she admits noticing he seemed less gregarious than usual. At one point during the festivities, a crisis occurred: One of the alums, classmates feared, was suicidal. Allen barely knew the woman, but he immediately took charge, tracking down her loved ones from his cell phone in the middle of a rainstorm in Harvard Yard, getting her to a hospital, and making sure there were adequate psychiatrists.

What few, including Carol, knew at the time was that Allen himself had had a breakdown at Harvard. It was at the end of his sophomore year, during which he tried to take too many classes while also playing trombone for the Hasty Pudding club and writing for the weekly Independent. Jean furiously rejects the suggestion that Allen had psychological problems, insisting that he had only needed some time off and came home for a year—where his father got him a job at a construction site in the city and he took a room at the 92nd Street Y.

But a retired Harvard professor who was the house master at Lowell House in the early seventies recalls a more complicated set of circumstances. “Basically, he had a nervous breakdown and wouldn’t move out of his dorm room, among other things,” says Zeph Stewart. “Eventually he had to be moved out.”

Stewart, who is 82, does not recall whether Allen was hospitalized in Cambridge, but he vividly remembers the episode because among other examples of Allen’s curious behavior was a series of nasty letters sent to Harvard administrators about Stewart, a professor of Greek and Latin. “He had been an extreme admirer of mine, and frankly I thought he was slightly unbalanced for thinking so well of me. But then he went from one extreme to another. He started writing these bizarre criticisms of me, saying that I was a fraud, that I wasn’t all that good a scholar. You could say it was slightly hostile,” Stewart says wryly. Years later, Allen befriended Stewart again. “Allen always stopped for lunch or tea when he was in Cambridge. It was as if that never happened, this ‘incident.’ I always liked him. But I was not astounded when I heard the news.”

After the reunion, Allen began to confide in Jean—telling her that he “hated his wife” and didn’t want anything to do with her, much less have children—but at the same time, he went through a new series of blood tests and psychological screening at a fertility clinic he himself had chosen. Carol was shocked to discover later that he’d been talking to Jean. Jean and Allen had had a falling-out, she says, when their father died in 1996, and “Jean wouldn’t speak to us for over a year.” (His therapist at the time described his family as “toxic.”) Jean downplays the estrangement, but in her eulogy for her brother, she spoke about how in his last months, they had gotten closer than ever: “With his newfound lease on life, he finally became the brother and friend I had always longed for.”

On July 22, Carol learned she was pregnant. Allen “sent me a big bouquet of flowers at work,” she says, and took her out to a romantic restaurant. Then he began divorce proceedings.

In court papers, Carol describes Allen’s family as “abusive and dysfunctional.” “Now you can see what a cruel bitch she is,” Jean retorts. “If we were all so mental, why was she so hell-bent on using his sperm?”

In the last three weeks of his life, Allen’s behavior grew increasingly erratic. He told different things about his wife to different friends outside the newsroom. To some, she was his “best friend” and his “only love,” and he feared he was “ruining his life.” To others, she was a shrew who had changed the locks, pirated his mail, and “stolen his favorite suit and his last roll of toilet paper.” He said conflicting things about the pregnancy—he wanted a baby, he didn’t want a baby. He also began writing notes to himself at his desk that would later be discovered: “If I can just think of it as in vitro, she did it herself, if I can hold that thought, I’ll be all right.” “You are going to get hurt deep down inside.” “Just stand up for yourself.”

Had any one of his friends gotten the whole download rather than select bits and pieces, it would have been painfully clear that Allen was unraveling.

To Carol, high on hormones and furious at his decision to divorce her, nothing made sense. But she says she believed that whatever he was going through, he would eventually snap out of it and come to his senses; he always had before. “Yes, we had some serious problems,” she admits. “But I still believed we would move into the new house and raise our children, everything we strived for.”

Allen was so conflicted that in the week after he filed for divorce, he still made time every day to inject his wife with hormones.

“I think she was the light of his life, his beacon of hope, really,” says Toddi Gutner, Carol’s closest friend at Business Week. “But when they started having problems, he went back to his family for the same support he got growing up.” Gutner believes Allen had painted himself into a corner, torn between his love for his wife and what his family expected of him—which was to finally leave her.

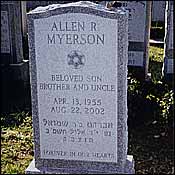

Within hours of winning the body battle, Jean ordered a headstone for her brother. Jewish custom calls for the unveiling of a headstone at the first anniversary of death, but Jean “wasn’t taking any chances,” as she puts it, that Carol might erect her own tombstone. And so in October, a tall slab of granite was placed at the grave in Queens that reads BELOVED SON, BROTHER AND UNCLE. “We felt that said it all,” says Jean.

“Tell me,” says Carol, “how I’m going to take his children to see that tombstone.”

On September 23, Carol’s birthday, she received notice of the lawsuit filed by Allen’s sisters in New Jersey Superior Court. Even in the initial filings, it was clear that the Myersons were loaded for bear. The main legal issue was whether Allen’s suicide note could be considered a valid will—the courts would have to determine that he was “of sound mind” when he wrote it, a dubious prospect but one that has yet to be ruled on. Later the sisters would level scurrilous allegations about Carol, including alleged details of her personal life in the years before she married Allen Myerson. The sisters also wanted their share of Allen’s possessions.

“We have nothing of my brother’s, not even a shoe,” Jean Myerson said in January. They prepared a list of demands. They wanted, among other things, his stamp collection, his trombone, the “five silver coins” mounted in blue velvet from his Bris, his prayer shawl from Jerusalem, their grandmother’s optometry chest and the needlepoint pictures she’d made a century ago in Russia, and his baby pictures. Carol argued that some of these items should be passed on to Allen’s children one day. But the biggest fight was over the wedding ring Allen had placed on Carol’s finger fifteen years before. The Myersons felt it was a family heirloom, their grandmother’s diamonds, and should rightfully be returned to the family. Carol, who still wears the ring, was incensed: “They’re accusing me of stealing my own wedding band.”

Then came the DNA battle. The sisters, one of whom is a doctor, wanted a paternity test done on the twins—in utero. The idea was quashed by the judge, after Carol’s OB/GYN wrote a letter saying, “This is not only extremely dangerous but one of the more absurd requests I have ever encountered in twenty years of practice.” (Carol agreed to do it after she gave birth.)

But this was all a warm-up for what occurred on February 13, when the parties gathered with their lawyers in a bank office building in New Jersey for a settlement conference. Carol, at this point eight months pregnant, and Jean, wearing one of her justice for allen buttons, crossed paths in the ladies’ room. “She was trying to give this button to me,” says Carol, “and saying I killed Allen. And I responded by saying, ‘Whoever convinced Allen to leave his pregnant wife is the person who killed Allen.’ And she just hauled off and hit me, really hard, across the face.”

Jean claims her pregnant sister-in-law attacked her: “She saw the button and started spewing profanities at me. ‘Up your ass, you little bitch!’ So I said, ‘His blood is all over you.’ And she came charging at me. I mean, charging at me. And so I defended myself—let’s put it that way. All I could think was, My God, this is what my brother lived with.”

The police were called to the bank. Though the police report identifies Carol as the “victim,” Jean has since filed a criminal-assault complaint against Carol. And Carol has reciprocated in kind.

After his suicide, Allen’s friends would be tormented that they didn’t sense a plea for help in his final days. But he gave none of them enough of the puzzle–though each of them had a piece.

In his last weeks, Allen was shedding weight, had lost his appetite, and was battling insomnia, according to one therapist’s notes (which were requested by the court and obtained by New York). He also “worried over obsessing about his personal problems as interfering with his ability to perform at work.” Only after his death, when Carol and Kevin Buckley went to pick up a suit to bury him in, and later when lawyers for both sides had to traipse through to itemize the possessions in dispute, did anyone see how he was living. The apartment he had once shared with Carol was a filthy mess, with clothes and papers strewn all over, the home of a severely depressed person, though he had continued to show up for work dressed fastidiously to the very end. Jean believes the condition of the apartment was “clearly staged by Carol”—to add to her case that he was not of sound mind—a charge Carol calls “ludicrous.”

But where were the shrinks? Records show he had been seeing at least three therapists (not including the psychological testing at the clinic) regularly throughout the spring and summer, one of whom was a psychiatrist who prescribed the anti-depressant Celexa and the anti-anxiety drug Xanax. But the prescribing doctor, who’d recently changed Allen’s dosage, was on vacation when he jumped; it was August, after all.

Later, all of his friends would be tormented that they didn’t sense a plea for help in his final days. But Allen gave none of them enough of the puzzle, though each of them had a piece.

On the weekend of August 10, soon after an ugly fight with Carol in front of the movers, he went to the Hamptons to stay with his friends Mark and Mary Leeds. “She doesn’t want me anymore,” Allen told them, according to Mark. “He kept saying ‘She’s such a pretty lady’ and ‘I miss her already,’ and that he didn’t want ‘to lose her. How could this be happening to me? We were so much in love.’ ”

The following Tuesday, August 13, he had much different things to say over dinner with Gilbert Kahn and his wife, Bernice. The Kahns were thrilled when, “out of the blue,” Allen had called them. It had been fifteen years since Gilbert’s refusal to be the best man at Allen’s marriage to a non-Jew had caused a rift in their friendship. The Kahns admit that when he told them why he was calling—that he and Carol were divorcing—they weren’t disappointed.

At dinner on the Upper West Side, he talked mostly about his plans for his new life. “He said he wanted to be with a Jewish girl the next time,” says Bernice. “And we laughed, and I told him that we would get on it.”

He told them that the wife he was divorcing was pregnant. “But he wasn’t sure he was the father,” says Gilbert. Moreover, in his version to the Kahns, “it was she who precipitated the divorce.” And Allen said that only after they split up had she told him, “And oh, by the way, I’m pregnant.”

He implied that he was really just the sperm donor—if the child was his. “The conversation was so fascinating,” says Gilbert. “He said, ‘It’s almost like I was used. I may just walk away from this thing.’ ”

Allen also told the Kahns, says Gilbert, that “the best thing that happened as a result of the divorce was that he had reconnected with his family. He really felt his family coming back.”

Two nights later, Allen met Bill Pinzler for dinner. Pinzler didn’t know him that well; they had met at an opening at the Museum of American Financial History. But in Allen’s last weeks, he reached out to Pinzler. That night, they went to see two rental apartments Pinzler had found for him. Then they went to Gabriel’s for dinner—where Allen proudly showed him his new “Patron of the Opera” card and “half seriously” expressed his wish to be the music critic at the Times.

That Saturday, August 17, he visited his family in Westchester to celebrate Natalie’s 79th birthday. Through the course of the birthday party, Allen and Jean had several whispering conversations in the kitchen. He repeated what he’d been saying for months, that he never wanted the house or the pregnancy, but also ratcheted it up a notch.

“He said that she threatened that if he tried to have anything to do with this baby, she would turn the child against him, make it hate its father,” says Jean. “He said he despised her so much he was willing to give over full custody.” He also gave Jean a copy of an unsigned document that he said he and Carol had drawn up, stating that he “not be considered the legal father of the child.” (Carol denies any involvement in creating that document.) In any event, it all should have seemed terribly contradictory: He was accusing her of threatening to keep the child from him at the same time as he was saying he didn’t want the responsibility. Natalie, in particular, was worried about the baby. “Allen, this is your child,” she told him. Couldn’t they work it out? But he told his mother, “If I go back to her now, I’ll never leave, I’ll never get out of that marriage.”

Jean responded with specific advice: He’d better have his lawyer do something about getting rid of the other frozen embryos. He needed to “protect himself”—that is, protect his assets, his job. “I said, ‘Allen, she is such a loose cannon. What if she accuses you of hitting her?’ ” She told him he’d better get tough.

The following Monday, Allen sent a long e-mail to his divorce lawyer that began: “Carol’s strategy, I believe, will be this,” followed by three pages of single-spaced rage in which he hit many of the points Jean had coached him on in the kitchen: They’ve got to get rid of the other embryos. How should he protect all his assets? And did he mention that she “dislikes Jews”?

That e-mail would be turned into the legal filing dated August 22 that he dropped, unsigned, in the mail to his sister before killing himself. When she received it a couple of days after her brother’s death, she was “touched,” Jean says. “I said, ‘Gosh, these are all the things I said to him.’ ”

Carol first heard the contents of the document when this reporter read it to her over the phone. For several minutes, she was speechless. Then she said, “This is not the Allen I knew.” In fact, she said, late the same night he’d written the letter, he’d called Carol and raised the possibility of a reconciliation. But she was tired, and pregnant, and very bitter; she told him they would talk in a couple of days.

On Tuesday, Allen had what would be his last therapy appointment. “In our last session,” the therapist later wrote, “I was struck by Allen’s conversation about apartments he was considering, a party he’d been invited to, and his decision to inform his boss that he and Carol were separating. There was no trace of any suicidal thoughts or intent. He was hopeful about a happier future.”

This therapist also wrote in her notes that throughout their recent sessions, “Allen was also in conflict about romantic feelings for another woman.” While the rumor at the Times was that Carol was cheating on him—something she vehemently denies—several sources say Allen was infatuated with a woman he repeatedly referred to in his scribbled notes, though only by her initials. (The woman did not return repeated calls from New York.) She was a “nice Jewish girl,” say friends, whom Allen had met at his and Carol’s book club. “Allen and I occasionally invited her to dinner,” says Carol, “to try to fix her up with single men we knew.”

On Tuesday, August 20, Carol had her last conversation with her husband. Calling at midnight, he’d awakened her to find out where she’d parked the car they were now sharing from different addresses.

The next day—the day before he jumped—an old friend from Wilmington, Delaware, came to the Times to have coffee with him, so concerned and shocked was he after Allen told him and his wife that he and Carol were splitting up. The two couples were supposed to be spending that Labor Day weekend, just two weeks away, together at an inn in Cape May. And now there was a divorce and a baby. “He didn’t sound morose, but it just didn’t make any sense,” says the friend. “Why would someone about to have his baby want to divorce him? It was just so disturbing.”

Over coffee, Allen assured this friend that even though this was Carol’s idea, and he was sad that “she doesn’t like me anymore,” and that there was a baby and all, he was fine. He’d be fine. But Carol had changed the locks. “I said, ‘Allen, this doesn’t sound like Carol.’ ”

That night, Allen met Kevin Buckley and Karen Wirtshafter at a restaurant in Jersey. Now he said that he didn’t really want a divorce but that his lawyer had told him to file. They were baffled. But their conversation kept getting interrupted by Allen’s cell phone. They were closing some big story at the Times, and so Allen spent much of dinner excusing himself to talk to the business desk. When he finally sat down long enough to really talk, he seemed most concerned about getting his new “bachelor pad” in Manhattan.

Karen and Kevin thought the whole night was weird, but not alarming. “He seemed a little down but was also reasonably animated,” says Kevin. Twenty-four hours later, Carol, now a widow, moved for several days into the couple’s guest room. They didn’t want her to be alone in her grief.

In the end, Allen made his death as difficult as he had made his life. When he stood up from his desk after slamming down the phone and scribbling his suicide note, he walked, deliberately but calmly, to the elevator. There were several people inside. “Where’s the terrace?” he asked. They told him the eleventh floor. Oddly, he then got off on the fifth floor. The only thing on the fifth floor of the Times is the emergency medical clinic. But Allen just paused there; he didn’t ask for help. He got back on the elevator and took it to the top.

Though he jumped from the fifteenth floor, the highest one can go by elevator is to the fourteenth. And one doesn’t usually go there uninvited. Fourteen is the plush floor from which the Sulzbergers rule. From there, he’d almost certainly have taken a grim back stairwell, rarely used and not terribly easy to find, to the fifteenth floor. He found his way to a very old corridor behind a room filled with audiovisual equipment. The corridor is lined with ancient windows that could, with great difficulty, be forced open. That is what Allen did. From there, he had to crawl outside along a parapet to a ledge overlooking the bright action of Times Square, from which he leapt to his death.

Myerson v. Cropper remains an open case. Carol recently put an offer on the table that would give more than half of Allen’s probatable estate to his sisters and the rest to the twins. Meanwhile, Jean was still mulling it over. Earlier, she had been trying to get the police and Manhattan district attorney Robert Morgenthau to investigate Carol for “aiding and abetting a suicide” and was livid that her calls were not returned. At one point she phoned to report that her private investigator had ascertained the names of the twins, then expressed her extreme dissatisfaction that New York won’t print them. But what about the children—Allen’s children? “My biggest wish,” Jean replied, “is that the paternity test comes back and they’re not Allen’s. That would be such a gift.”

Before the spring thaw, I go with Jean and Natalie to visit Allen. “I’ve been coming here since I was a little girl,” Natalie says as Jean navigates her mother’s old Mercury through Queens to the Mount Judah cemetery. By way of introduction, Natalie—a soft, sweet woman with tight white curls and wire-framed glasses—turns to me from the front seat and says, “She killed my son. Turn right.” She was talking to Jean. “I know that, Ma,” Jean snaps.

Jean has some business to attend to first in the cemetery office. She asks for the manager. “A woman has threatened to remove my brother’s headstone,” she tells him. “You wouldn’t ever allow that, would you?”

“Never!” he replies.

“Even in the middle of the night?”

“Never!”

She later admits that Carol had not in fact threatened to slip into Mount Judah in the dark of night and remove Allen’s headstone, but Jean Myerson isn’t taking any chances.

Natalie walks outside and picks up a stone to lay on Allen’s grave. Then she walks to the spot where her only son is buried. The dirt is still in a pile in front of the headstone that says everything but husband and father. “What a waste,” she says, sobbing. “What a sin.”