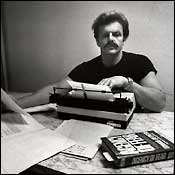

It’s 9 a.m. on an already hot July day, and Richard Stratton, a new TV exec, has finished up a half-hour of phone calls—TV, he’s learning, is endless calls, endless snags. The writers won’t arrive till 10—he’s learning that too—and in the meantime, he’s peeking at some recent episodes of his show, Street Time. Stratton isn’t tall, but he’s wide, taut, and, even at 57, imposing (to stay in shape, he does three sets of 70 push-ups every so often). He takes a spot on a small couch, the one piece of real furniture in the West 26th Street offices.

Rob Morrow appears on the TV screen. In Street Time, the former star of the quirky Northern Exposure plays an ex-con who spent five years in prison for smuggling pot and hash. Morrow’s character is likable, hippie-ish.

He’s gotten out of jail only to return to the drug business. He smuggles hash into New York in containers of dates. In the episode on the screen, someone has stolen most of his shipment; a container has been left at the docks for him to pick up. It may be a setup.

What will Morrow do? What’s realistic? That’s what the writers had asked. Stratton, though, always knew exactly what Morrow would do, and with good reason.

“This happened to me,” says Stratton, who spent eight years in prison for smuggling hash and pot. “The load was coming into Brooklyn. The DEA had stolen part of it. I saw this hash on the street that had my stamp on it. They’d left one container at the docks. It looked like a setup.” Stratton, though, decided to pick it up anyhow, which is what Morrow does in the show. “I loved to see that I was under surveillance and then to try to lose the guy,” Stratton explains. He sent a guy to get the load in a truck.

On the couch, Stratton’s usual expression, a kind of half-scowl, slips away. “I’m in a rental car waiting to see if they follow him,” he says, getting animated. “Sure enough, they were there. I pull up next to the truck, trying to signal that he had heat. I used all this for the show.” The tale seems to excite him. “We raced to the stash house,” Stratton says quickly. “We got lucky and lost them for about 45 minutes”—time enough to destroy a tracking device and unload the truck, just as it happened on the TV show. The cops eventually arrested Stratton in the truck, but by then the truck was empty.

“Where’s the hashish?” Stratton’s lawyer challenged the prosecutor in court, just as an actor playing a lawyer challenges the prosecutor during an episode of Street Time.

So it goes. Stratton watches episodes as if they’re home movies (with terrific production values). His intent look, the one where his forehead buckles over his brow, disappears. The strange doppelgänging of his life and his TV show produces delight. “That happened to me,” Stratton says every few minutes. (There onscreen is a character based on the guy who testified against him in real life. And the guy who ratted him out. And a guy sitting on a toilet in a prison cell: “This guy in my cell seemed to be taking the world’s biggest dump,” he says. Onscreen, the actor produces a baggie of heroin, which of course happened to Stratton. Did he do the heroin? Of course he did.) “When we get stuck,” explains one of the show’s writers, “Richard will start telling a story about jail or running drugs out of the Bekaa Valley or prison, and usually it finds its way into the script.”

Has there ever been a more creatively productive ex-con than Richard Stratton? In the thirteen years since the federal prison system let him go, he has consulted on the HBO prison documentary Thug Life in D.C., which won an Emmy, and produced Slam, an independent film that won awards at Sundance and Cannes. (Both were produced by Stratton’s partner, Marc Levin.) He’s started a magazine, Prison Life, with his wife, Kim Wozencraft—ex-cop, ex-con, author of the best-selling Rush, and mother of their three kids. He’s published a novel, Smack Goddess, about drug smuggling, and written journalism about prison for GQ and Esquire. Few have so chillingly, and movingly, captured the prisoner’s experience. And Street Time, the series on Showtime, may be his best work yet. This drama about parolees and their parole officers, which Stratton thought of as he was waiting to meet with a parole officer (“a prick” who was sure he’d return to prison), is a story of complicated people on both sides of the law struggling to do the right thing.

Says Rob Morrow, “On set, we joke that crime does pay.”

Stratton’s biography is irresistible, perhaps especially for showbiz people. (“He’s a superhero,” says one of the show’s writers. “A Hemingway character,” says one of the actors.) And yet what makes the outlaw résumé most intriguing is that for all his criminal experience, Stratton doesn’t seem like a criminal. As his wife puts it, “He’s a middle-class kid from Wellesley, Massachusetts.” He dropped out of Arizona State University to join the “hippie mafia,” the drug-running one. He hit the hippie highway, as he puts it, with stops along the way, notably in the Middle East. There, Stratton befriended some Lebanese Shiites, controllers of the hash trade. (“That was really my area of expertise: being able to get close to those people and get their trust. I tried to give them like a half-million in cash. But a load might cost 3 or 4 million.”) Soon, he was one of the country’s largest importers of high-quality pot and hash. (He provided samples to the magazine High Times for its monthly taste test. Later this year, events will come full circle when he becomes the magazine’s editor.)

Not long after he began smuggling, Stratton, also an aspiring writer, became pals with Norman Mailer in Cape Cod, where they both lived. “I was a little bit smarter and he was stronger,” says Mailer. “We drank, boxed, talked,” and, occasionally, head-butted. (Stratton’s forehead turned blue with bruises.) After he left prison, he sometimes stayed at Mailer’s Brooklyn Heights apartment. “I’d point down to the docks,” he recalls. “Right there,” he’d tell Mailer, indicating the spot where he’d brought in tons of hash hidden in shipments of dates.

By his twenties, Stratton was an international drug entrepreneur who controlled a trucking company, a warehouse—he actually sold the dates—4,000 acres in Texas, a horse farm in Maine (co-owned with Mailer), as well as a lodge there; the lodge and the Texas spread featured landing strips.

Mailer once wrote that the “hipster” ought to follow his orgasm—for Mailer, a middle-class kid, the middle class was “a barbed wire cocoon.” “I guess that’s what I was doing,” says Stratton. There certainly was lots of excitement. “It was a high waking up in the morning and thinking, Am I going to get arrested today, or am I going to make $4 million?” That was a real number. Stratton typically made $3 million to $5 million on a big load, which he’d bring three or four times a year.

And so, in addition to whatever else he was—hipster, hippie drug lord, man of action—there was also this: Stratton was rich. He seemed to have an endless supply of money. He bought Thoroughbred horses. He bred German shepherds. He had houses in New York, the Bahamas, Hawaii, and Colorado, and probably $6 million in cash. “I spent a lot of it,” he says. He’d stay at the Plaza Hotel for months at a stretch, buying hookers and $100 bottles of Dom Perignon. Or else, he says, “I’d wake in the morning and say, ‘Hey, let’s got to France,’ and we’d hire a Lear jet and go to Paris.”

Not everyone thought Stratton was leading a terrifically exciting life. Before prison, his mother says, “he was a real asshole.” Stratton, too, wasn’t always contented. “Sometimes, I’d take walks early in the morning and ask myself, Why am I doing this? I’m going to get caught,” he says. “Well, okay, I thought. Then I’ll go to prison and write.”

Stratton was arrested in Maine. To make bail, he put up the horse farm he and Mailer co-owned, then fled to Beirut, where he lived for a year. (Apparently, he wasn’t quite ready to write. In 1982, he was lured back by the promise of a payday: $6 million owed to him and his Lebanese partners. He snuck into the country and showed up at a Los Angeles hotel where most of the hotel staff had been replaced by federal agents, some of whom vaulted the front desk to arrest him.)

Prosecutors, though, wanted someone else besides Stratton. “They thought Mailer was our spiritual godfather,” says Stratton. They offered him a deal to testify against Mailer, among others.

“I never said to him, ‘Don’t do it,’ ” says Mailer, meaning drug smuggling. “As a novelist, I was fascinated. The DEA was hoping I was involved; it would have been juicy for a couple of guys and their careers. But it never occurred to me that he would testify against me. He would have had to lie.” Â

In any case, Stratton refused the government’s offer, and the judge punished him to, as she put it, convince him that cooperation with the government was in his best interest. When he finally arrived at his creative stamping ground, he was 36 and had a 25-year sentence.

In prison, Stratton finally wrote fiction, though just as important, he wrote legal briefs. He appealed his case and won. The government could punish him for his crimes, but not for failing to cooperate. After eight years in prison, Stratton was on parole. Soon he’d published a novel—Mailer had hooked him up with his agent. Stratton’s release summoned memories of Jack Henry Abbott, a convict-writer previously championed by Mailer who’d murdered a young man outside a Second Avenue restaurant. Art is worth a risk, Mailer suggested at the time, causing some to wonder if Mailer’s next prison protégé represented the same order of risk. But Stratton was an intelligent, upper-middle-class kid, a former hippie, an action junkie who happened to spend the Reagan years in prison. Indeed, to hear Stratton talk, prison was a learning experience, something like a Zen retreat. “You’re stripped of all the stuff that we think of as what we are: job, apartment, bank account,” he says. “It caused me to look at who I was and what was getting me off. I learned humility. I spent a lot of time thinking, Do I want to spend the rest of my life like these offenders? Or do I want to try to do something else? Which is what our show is about.”

So fascinated is television with crime—is there any law-enforcement procedure that doesn’t have its own series?—that a show about parole seems almost inevitable. For someone with Stratton’s background, the position of technical consultant—his title on Oz—made sense. Stratton, though, thought Oz was over-the-top; he wanted creative control of Street Time. When Showtime balked, he decided to film a test pilot of his own. “I’ve always been a risk taker,” says Stratton. “That’s what got me in so much trouble.” He recruited Mailer and one of Mailer’s sons to act in it—they were offender and parole officer, respectively—and put up $30,000 of his own, which put heavy strains on his marriage. Wozencraft understood her husband’s taste for risk; as an undercover narcotics cop gone bad, she enjoyed risk herself. (Stratton’s parole officer had at first objected to the wedding—“You can’t associate with criminals,” he was told.) Still, Wozencraft thought the expense unnecessary. In any case, after seeing the test pilot, Showtime paid for a pilot of its own and then signed up the series (which begins its second season August 6).

Still, Showtime, the network, and Sony, the studio that helps fund the production, weren’t going to trust Stratton to run the show. Why would they? Stratton had never worked on a TV show except in his brief stint as technical adviser. As he points out, “They didn’t really want this crazy, ex-drug-dealing ex-con running things.” A TV professional was hired: Stephen Kronish, a likable guy with solid credentials—MacGyver, The Commish, Profiler—whose first advice to Stratton was, Don’t talk to the actors; they’ll just get out of hand. On set—the show takes place in New York but is filmed in Toronto—Stratton stewed. Privately, he complained to Scott Cohen, who plays Rob Morrow’s parole officer. “This is over-the-top,” Stratton said. “This is a totally wrong direction.”

“Why don’t you say something?” Cohen prodded.

“I don’t want to step on any toes,” said Stratton.

“Get your shit together,” Cohen said. They yelled at one another for 45 minutes until Cohen thought, What the fuck am I doing? I’m yelling at a guy who could take one swing, and I’m out.

‘I never said to him, ‘Don’t do it,’ says Mailer, meaning drug smuggling. ‘It never occurred to me that he would testify against me.’

Soon Stratton and the network were butting heads. “We fought constantly,” he says. Stratton sent a memo complaining that the show was becoming “formulaic.” “This is not how I want my show to be,” he said. The network flew Stratton to California to huddle with the writers in their office; the writers, though, never showed up. Kronish threatened to push Stratton out.

In prison, Stratton had been in a few fistfights. But intimidation among convicts is often more verbal than physical. In prison, he says, he learned “the ability to back a guy down, to scare the shit out of him.” It was a technique he occasionally found himself using with TV executives. A Showtime exec says people are always getting passionate, but as one writer on the show explains, “Richard’s prison past gives him an extra weapon. He’s working from a place few other guys are.” One day, Stratton screamed into the phone at a Showtime executive: “What the fuck are you talking about? You don’t know shit about what it’s like in prison. You can kiss my ass.”

Early in the first season, Erika Alexander, who was on The Cosby Show, plays a sexually smoldering parole officer—“Write me like a man,” she’d said—finished a scene and then turned to Kronish. “This is corny,” she said. “This is bullshit.” She played it as a joke. But someone made sure that Alexander’s remark found its way into the dailies. Soon after, Kronish stopped reporting to work.

The network still wasn’t about to appoint Stratton to replace him. By default, though, Stratton started rewriting most of the scripts. The show borrowed more and more from the Stratton biography—and the Richard Stratton–Marc Levin style. “You show up,” says Morrow, “and hope to combust.”

Like The Sopranos, the show seems to have succeeded in taking the conventions, the props, the menace of criminal life and reconfiguring them as elements of an essentially middle-class drama. The Street Time drama is one in which the important elements are relationships and feelings. Showtime picked up a second season. Stratton and Levin, though, held out. If they weren’t officially put in charge, and if the writers weren’t moved to New York, they wouldn’t sign up. Showtime came through on both counts.

Stratton’s a TV guy now, the show-runner, which comes with its own kind of pressure. As the second season gets under way, the time between finishing a script and filming is already down to five days—then they get seven days to shoot each $1.3 million hourlong episode. “It’s a runaway train,” says Stratton. The season hasn’t aired yet, and the Jeff Goldblum episode still has to be written. (He wants more danger in his character. “Let’s have him belt the guy,” says a writer, to which Stratton suggests that no, it’s better if “he does the prison thing,” backs the guy down, intimidates him, and then says, “I learned that in prison.”) And the Serena Williams story has unresolved issues like, as Levin puts it, “Can she act?” Sony wants episodes to be more “episodic.” And at one story meeting, a Showtime executive is concerned about characters’ motivation. (“You guys just make it up as you go along,” he says.) And then there’s Larry Goldman, a short, tattooed federal parole officer, the show’s technical consultant, who is desperately trying to keep it real. (He’s got a list of objections in his pocket. Like, for instance, a parole officer would never rape an offender, which happens in one episode.)

For Stratton, there are a lot of demands to juggle. “It’s like the drug business, dozens of phone calls and people not doing what they said they’d do,” he says. But TV is not the drug business—a bad episode won’t get you sent to prison. Stratton has a colorful life now—at his parties, you can meet an armed robber, a guy on the lam, Norman Mailer, or beautiful actresses saying things like “It’s so hot in here I think I’m going to take off my bra.” But these aren’t the days of waking up and wondering if you’re going to jail or going to make $4 million.

And that leaves an observer wondering if the conversion from drug outlaw to dad and TV exec is complete. Stratton, whose red hair is streaked with gray—suddenly, it seems to him, in one haircut—considers the question. When he got out of prison, he says, he had to decide whether to turn his back on the drug business. “I was probably owed 3 to 4 million when I came out,” he says. Most of that he never collected. “Some people came to me and offered me money to buy my connections, and I wisely said, Forget the whole thing, because some of those people ended up cooperating with the government. At that point, I realized that I had to sever all my ties to that world.”

Morrow’s character—the Richard Stratton character—makes a different choice. He leaves prison and gets back into smuggling. He sets off to lead the life that Stratton gave up, as if TV could experimentally answer the question What might my life have been like? It’s a strange question, and not an idle one. Because Stratton does miss the life, parts of it. “The absolute freedom,” he says, “I miss that.” And yet, one reflex following another, he quickly adds, “I don’t miss the paranoia and the fear that at any minute I could be arrested and taken away from my family.”

And Stratton hopes for the same for Morrow. “He’s got to learn,” says Stratton of the Morrow character. “I’m rooting for him to make the right choice.”