It could be that chat kills people. The unfettered expression of fantasy – and worse, the automatic search function that links your fantasy to like-minded ones – so exacerbates a wacko predisposition (and what teenager doesn’t have a wacko predisposition?) that cyberchat, rather than guns, is the real cause of teen mayhem, Charlton Heston and friends might argue.

Of course, teen mayhem and teen media have always had a close connection, at least in the minds of news magazines, morality self-promoters, and parents at wit’s end.

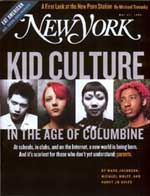

The Columbine killings – with chat rooms, Websites, multiplayer games, and the general weirdness and unknownness of the Internet taking the rap – represent something of a new-media rite of passage. Such finger-pointing is always about selecting a target that you can’t miss. So what’s really being said is that new media is big media, that it’s everywhere, and that, by virtue of its sudden, shocking ubiquity, along with its disconcerting newness, there’s a pretty good chance it has something to do with what’s going wrong.

While this is not an intelligent analysis, that doesn’t make it any less true. As Internet media becomes pervasive media – pervasive like rock and roll – it will no doubt precipitate a shift in teen personality, behavior, aspirations (not to mention parental relationships). In other words, here we go again.

I was the parent brought in to talk about the Internet on Media Day at my daughter’s high school last week. I tried to suggest beforehand that these kids probably didn’t need a parent to talk about the Internet. Newspapers, sure – get an editor. Television – get a producer. But the Internet, unless you wanted to get an investment banker to talk about IPOs, seems, at least for teenagers, self-evident. The school, though, was determined to have an expert (me).

Well, I tried to broach the subject of the power of this new medium with the story of a media mom (quite a megamedia mom, at that) who, over lunch with me, was really vociferous about the evil of the Internet: It was like a drug; it entrapped kids; obviously there was a parental responsibility to draw the line somewhere against threats to our children’s innocence. When pressed, however, for an explanation about the extreme nature of her views, this heretofore-liberal media executive admitted she was feeling particularly uncharitable because the Secret Service had visited her home in Brooklyn after her teenage son threatened the president on AOL.

There was a sudden wave of tittering from my daughter’s classmates and furtive looks. The Secret Service, it seems, had just shown up at this school. Someone here, from the computer room, had threatened the president, too.

What are we to make of this? Is it meaningful or meaningless? Does the Secret Service run a search bot on key words related to presidential death threats? Should every high school be running its own malcontent search engine? Can technology distinguish lethal threats from idle ones? Count on it: Someone’s already speccing the code and writing the business plan.

Then there were the milder reports from this teen frontier: From sensory and narrative recombinations (simultaneous chat, television, and phone) to lame and ineffectual parental controls (“My friend is so addicted that when her parents took away her AOL privileges, her friends had to give her screen names”) to new social sensitivities (“I mean, I might not like the person in real life, but, like, they’re really great to chat with”) to a novel perspective for Manhattan kids ("Like, everybody’s from Ohio”) to the real attraction ("You can just relax, be yourself, like, be in your own world”).

And then there were the teachers’ facial expressions – in this mirror you really see the shock of the new. Could they express any more vividly their distaste and incomprehension? As much, I suppose, as you can count on teens acting like teens, you can expect teachers to act like teachers. What scowls!

All media, or all mass media, are teen media. If you can’t appeal to teens, you don’t have a mass-media business model. You need teen obsessiveness, the market power of teen compulsion. To get at it, you have to offer something forbidden; some taboo has to get broken: It’s evident in the lovely, sensuous, compelling voyeurism of films, or the crossing of racial lines with rock, or the sloth of television, or porn on home video. Now the Internet comes along, letting you circumvent one of the strictest taboos of all: It lets you talk to strangers. What’s more, it gives you technology that lets you custom-select a stranger (or the stranger to select you). These aren’t random, off-the-rack strangers. Hell, no. These are strangers who share your darkest secrets, your most nagging itches, your most violent inclinations. If you’re a Quake fan, or a Hitler aficionado, or a pipe-bomb enthusiast, you could have found Eric Harris and sent him an instant message: “Hey, what’s up, man? Got any A.H. birthday plans?”

Strangers in cyberspace have all the advantages of imaginary friends – you can imbue them with any characteristics you want to imbue them with – without the overriding disadvantage that they don’t exist. Online, your imaginary friend really talks back. The realness, or potential realness, is part of the compulsion here: Whenever you want, you can take this unreal world and make it real. It is sci-fi in its dimensions. You have this fantasy; you’ve developed it, plotted it, played it out. Now you have the power to keep it a fantasy – or make it real. At this moment, at malls across the country, at Bennigan’s and Quality Inns, there are men and women – and boys and girls – imaginary friends, anxiously waiting for each other.

But, in fact, the desire to make it real is probably not the main desire. Cybering – “Do you cyber?” “Want to cyber?” – is a re-creation of the age of sexual experimentation and freedom, of the famous seventies grail, the zipless fuck (except that in cyberspace, there are no health fears or weight issues).

Soon enough, responsible parents are going to have to sit down with their children and say, “I want to talk to you about cybering.”

As a positive by-product, cybering may be reinvigorating the narrative form. People tell stories. True stories, and not-true stories. It’s a new oral tradition. Amazing stuff. Attention, English teachers!

All media is nerd media – that is, it starts with an antisocial appeal, or an appeal to the disaffected. After all, media – the most successful media, anyway – offers an escape, it takes you out of where you are. For twenty years, new media – bulletin boards, news groups, multiplayer games – has been the frontier of the socially inept and the land of the sexually disaffected (“If spankers had a nation,” wrote the Internet journalist Ben Greenman, “alt.sex.spankers would be their Congress”).

But something must happen for disaffected media to become mass media. In this instance, the catalyzer is AOL – doing for the Internet what the Beatles did for rock.

First, there was the onslaught of a billion disks spread out over the nation. Unavoidable, omnipresent, irresistible. Filling the nation’s sock drawers. Then there was the startling explicitness of AOL’s conversations – tens of thousands of dirty chats. (Everybody knows the business rule that a new medium must expand the borders of prurience. AOL’s competitors, on the other hand, CompuServe and Prodigy, never quite understood that media – i.e., dirty chat – was the business they were in.) But disks and dirty chat were just the early stage of the medium’s development. The real crossover into mass media began in early 1997 with two developments.

“Flat pricing,” identifies a boy at my daughter’s school (kids always know tons about the media they are most enthralled with; the point about jock culture, for instance, is not that you play sports but that you watch sports).

“And the buddy list,” adds a young woman.

Before flat pricing – AOL went from an hourly charge to a fixed monthly fee – you were spending your parents’ money. You were monitorable, accountable, and, inevitably, irresponsible. After flat pricing, AOL was just a sea of time, oxygen. Before buddy lists, you had to contact someone: It was phone-call-ish; it required a conscious act. With the buddy list, it was like television: The world – your world – just appeared before your eyes. In addition, it’s an omniscient world. Matter of fact, if you push the concept, it’s a world of maximum knowledge. Everyone knows where everyone else is, what everyone else is doing, who everyone else is speaking to. A perfectly level playing field. The problem with cliques is not that they exclude you but that they are mysterious. AOL gives you the power to know not only what your friends are doing but what your would-be friends are doing, and your enemies too. This may not be bad.

Marketers say that when you achieve a 10 percent penetration of American households, you hit a magical point of no return. That’s where the snowball effect occurs – that combination of word of mouth and keep-up-with-your-neighbor anxiety, when it’s easier to go along than not go along. AOL hit 10 percent about eighteen months ago.

So every family is an AOL family – or soon will be. Seventeen million now. Looking to 35 million by 2002. In other words, there’s not a lot of chance of going back.

It’s ten o’clock. do you know where your teenager is? You don’t. You don’t have the vaguest idea. Worse, you don’t even know that you don’t know where your teenager is. This is partly because you’re stupid – the divide between what your child knows about technology and what you don’t is going to be the source of tribulation and comedy for years to come. Now, it is true that unless you run a cyber company or are having cybersex yourself, there isn’t a lot of reason to know about personal profiles and chat rooms and IMs and buddy lists and scanners and real-time audio players. But here we are.

And this is where your kid is. Down the hole. After the rabbit.

I could tell you how to follow your teen, pick up his or her trail, preserve those wayward electronic footprints, but you wouldn’t do it anyway – you’re as likely to follow your kid into cyberspace as you are to program your VCR.

But if it’s any consolation, this is not about teens, and it’s not about violence, and it’s not about you – it’s about media. That means that it will get larger and larger and more pervasive and more engulfing, and in fairly short order, it won’t be strange or threatening at all, but just what we do – just the technology that facilitates the context in which we live. Or else it won’t, and then we’ll give up on it and do something else.