At 8:30 on the morning of September 14, 2004, some 400 employees, virtually all of Saatchi & Saatchi Worldwide’s New York office, gathered in an agency conference room for what most thought was a regular company meeting. Kevin Roberts knew different.

The 55-year-old Roberts had been named CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi Worldwide in 1997 and had presided over something of a company renaissance. Founded in London by the brothers Charles and Maurice Saatchi in 1970, the agency became the U.K.’s largest in less than a decade. Its “Labour isn’t working” campaign helped usher Margaret Thatcher into office in 1979, and Saatchi went on to become one of the world’s most storied ad firms, creating memorable ads for clients such as British Airways and M&M Mars. By the nineties, however, the Saatchi brothers had nearly bankrupted the agency, and by December 1994, they were removed from the company’s board in an internal coup. In 1995, a new parent company called Cordiant was formed. Still, the agency floundered.

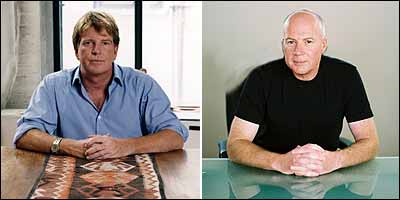

At first, hiring Kevin Roberts smacked of desperation. He had never held a job in advertising, but he did possess some of the panache of Maurice and Charlie. The antithesis of the Greenwich man in the gray flannel suit, Roberts dressed in Armani black, was known to place colleagues in headlocks, and caroused and cursed with a British lad’s zeal. Roberts was raised in Lancashire, England, but the high-school dropout adopted New Zealand as his country and spoke in an over-the-top Kiwi accent. Roberts is an outsize character, wildly enthusiastic about his work and given to Tony Robbins–style motivational speeches. And he wasn’t above a stunt or two. In the late eighties, at a black-tie corporate dinner in Toronto, Roberts, then president of Pepsi Canada, walked onto a stage. A Coke machine was wheeled out. Roberts reached behind a table, pulled out a machine gun, and proceeded to blast the Coke machine. They were only blanks, but it made an impression.

Roberts’s guiding marketing star is a concept he calls Lovemarks, a simple theory holding that there is a magical place beyond brand loyalty where worshipped products like the Volkswagen Beetle, Guinness beer, and the iPod reside. Roberts’s goal was to take Saatchi clients like Tide and Pampers from loyalty to Lovemark. To that end, he immersed the company in Kevin-speak. There were posters in the lobby reading A LOVEMARK IS LIKE A GREAT LOVER. NEVER BORING. On the Saatchi Website, Roberts wrote, “Darwin would have got it straight off. Product to trademark. Trademark to brand. Brand to Lovemark. Lovemarks are super-evolved brands.” Then there was Peak Performance, Roberts’s path to boosting productivity. A sample tenet: “You either fear change and duck for cover, or you revel in it. I’m with the Chinese sage who said, ‘When you’re caught in a storm, don’t run for your life. Build a windmill!’ ”

Roberts was just as good at selling the Roberts brand as he was at selling Tide. He trotted the globe, padding his reported $1.9 million salary with seminars and book sales.

As CEO, Roberts rededicated Saatchi to its core clients, on the theory that it’s easier and more cost-effective to generate new business from people with whom you already have a relationship than to chase new clients. In large part, it worked. Longtime Saatchi client Procter & Gamble, for example, shifted brands like Pampers and Oil of Olay to the agency, generating millions in new billings. In 2002, Ad Age named Saatchi & Saatchi its agency of the year, noting the company’s revenue had increased from $6.6 billion to $7.9 billion that year.

One man waiting for Roberts to speak in the Saatchi conference room that September morning was Mike Burns. Despite being seven years younger than Roberts, Burns was advertising old-school. An Irish-American son of the Bronx, Burns went straight into ad work after college, and, in 1980, took a job at Dancer Fitzgerald Sample, a buttoned-down firm that had been handling the Minneapolis-based General Mills account since before the Depression. He was just 23. A quarter of a century later, Dancer had been swallowed by Saatchi in a merger, but General Mills still has dozens of brands at the agency, including Cheerios, Yoplait, and Pillsbury. As the General Mills–Saatchi partnership entered its ninth decade, General Mills was providing Saatchi with $500 million in billing, 50 percent of the New York office’s total revenue.

For his entire adult life, Mike Burns worked on General Mills. He never married, never had children; he must have made the trip to Minnesota more than 500 times. He worked with some of the same people for twenty years (he is godfather to the children of Anne Adriance, his longtime No. 2 on the General Mills account). Burns eventually became the powerful head of the General Mills “silo,” a Saatchi term for an agency-within-an-agency arrangement in which the firm’s major clients were largely independent from one another. He was the most important executive on the agency’s most important account.

Where Roberts is loud and larger-than-life, Burns is quiet and earnest. “Negativity, cynicism, and sarcasm are the leading causes of death when it comes to organizational confidence,” he told me at one point. “They don’t help the brand.” Detractors joked that Burns dreamed about General Mills. The rest of the agency’s clients, they said, didn’t exist to him.

At first, Kevin Roberts’s appointment as CEO was greeted by Burns with a shrug. After all, Burns and his team had survived mergers, palace coups, and other forms of corporate mayhem. Besides, the General Mills account was Saatchi’s cash cow. Surely, no one would meddle with that.

It wasn’t long before Roberts and Burns clashed. At first, it was merely personalities—the flamboyant Roberts and the quiet Burns simply rubbed each other the wrong way. Then it became corporate. While Roberts managed the Procter & Gamble account, he watched as General Mills flourished under Burns, largely without Roberts’s help, and with only the barest of lip service to Lovemarks.

Late in 2003, Roberts appointed Burns co-CEO of the New York office along with Saatchi veteran Scott Gilbert. But within months, Roberts changed his mind. He told Burns he was dissatisfied with his silo-breaking efforts (Roberts wanted more cooperation between agency teams) and said he would be hiring a sole CEO for New York from outside the agency. Gilbert would be let go, and Burns would go back to the General Mills business. Burns never had a strong desire to be CEO, but the way Roberts handled the situation humiliated him. Burns squirmed while the search for a new CEO went on for six months. The tension between the two men got worse when Roberts approached Anne Adriance about transferring out of Burns’s group to become head of human resources, without consulting Burns. Roberts says it was a promotion, but Adriance was frustrated; to her, it was a way of being kicked upstairs. Burns thought Roberts was dismantling his team.

The final breach between Burns and Roberts began the night before the September 14 meeting. According to Burns, a Saatchi human-resources executive called him to tell him that a new CEO would be announced the next day. It was the first Burns had heard a decision had been made, and the HR staffer, he says, wouldn’t tell him who had been chosen.

“You’re not going to tell me who is coming in?” asked Burns.

“No, we’re not. There is concern about a leak,” said the HR staffer.

“I’ve been here 25 years, and you won’t tell me so I can prepare my clients?” asked Burns.

“No.”(Roberts insists he, not an HR staffer, called Burns.)

The next day, Burns came in, as usual, at 7 A.M. He worked out in the company gym, showered, and then took the elevator down to the conference room.

The meeting began with the departing Gilbert offering a few remarks. Then Saatchi New York creative director Tod Seisser had the lights dimmed. Known for his dry, Woody Allen–like wit, Seisser played a reel of the agency’s latest commercials. After a few minutes, the lights came up halfway.

“This is a little emotional for me,” said Seisser, his voice trembling. “This is the last reel I will show. I’m leaving the agency. I’m really proud of the work we’ve done.”

There were gasps. A few people burst into tears. The room fell silent. Then a man dressed all in black walked toward the front.

It was Kevin Roberts. He grabbed the mike and strolled the stage like an Evangelist. He shook hands with Seisser and said, “I’ve been ‘in like’ with Tod from when I first met him. I’m still in like with him. But I need to love somebody, and we need to win more awards. We need to go in a different direction. It’s a new bus; either you’re on the bus or you’re off the bus. These are my new rock stars.”

From the back, new CEO Mary Baglivo and new creative director Tony Granger walked to the front. “This is Mary Baglivo,” said Roberts. “I lusted after her for eight years … professionally.” Roberts laughed, but few others did.

Roberts then railed about what he felt ailed the agency: average work, poor client relations, and a lack of profitability. Burns and his team took it as a slap: Roberts never mentioned that the General Mills account was hugely profitable or that, in Saatchi’s annual internal ratings, General Mills had never rated the agency higher.

As Roberts wrapped up his speech, he looked for Burns in the audience. Almost immediately, Roberts says, he regretted that he hadn’t given Burns ample time to absorb the news. “My heart sank,” says Roberts. “He was red and upset.” Burns later e-mailed Roberts saying he couldn’t believe Roberts had made Seisser attend his own funeral. “I found that strange,” Roberts says. “It was Mike who was most insistent that Seisser had to go.” (Burns denies that.)

No one was surprised when Mike Burns resigned on February 11, but what happened next shocked the ad world. At 5:30 P.M. on February 14, seventeen of Burns’s disciples on the General Mills account quit en masse. The choice of Valentine’s Day was a special fuck-you to Roberts, who had turned the holiday into a Lovemarks-related day of Saatchi-and-Kevin celebration. Within days, Interpublic, a Saatchi rival, collectively hired the seventeen at an estimated cost of $3 million a year in salaries.

Rumors swirled that General Mills’s business would move with the Saatchi 17, as the trade press dubbed the renegades. A stunned Roberts ordered a company lawyer to query some of the remaining General Mills staff in hopes of finding out what they knew, and when they knew it. Later that week, Roberts flew to Minnesota and asked the same questions of the General Mills brass. He says he confronted Steve Sanger, the company’s CEO.

“Were you party to this?” Roberts says he asked Sanger.

“No,” said Sanger.

“Will you keep the business with us?” Roberts asked.

“Yes, but you gotta perform,” said Sanger. “Make sure no balls get dropped.” (Sanger did not return New York’s calls regarding the conversation; in February, General Mills issued a statement reaffirming its relationship with Saatchi, but has otherwise refused to comment on the Saatchi 17.)

Although Burns was never offered a job at Interpublic, Roberts didn’t believe that the Saatchi 17 would have left the agency without Burns’s counsel and blessing, and he feared that Burns might join them at a later date (this despite the fact that Burns had a clause in his separation agreement that prevented him from working for or soliciting business from General Mills for one year). Roberts instructed Saatchi lawyers to sue Burns for $3 million. The suit accused Burns of fiduciary neglect by urging General Mills to defect while still on the Saatchi payroll.

It’s hard to overstate the impact the defections had in the ad industry. Trade reporters staked out Saatchi’s offices in the February cold, asking anyone who was leaving if he was part of the Saatchi 17. Ad Age hired paparazzi—they surprised Burns outside his apartment one evening. “Hey Mike, Saatchi’s going to screw you on that lawsuit,” one shouted, trying to goad Burns into an angry reaction.

Four months later, Mike Burns has spent tens of thousands in attorneys’ fees and remains unemployed. Back at Saatchi & Saatchi, Kevin Roberts has tried to rally the troops, but a pall has fallen over the agency’s remaining General Mills staffers as they confront the reality that they may be asked to testify about their longtime mentor. (Last week, Saatchi received five Effie Awards, a coveted industry honor. Current staffers were credited for three of the winning campaigns; members of the Saatchi 17 were cited for two.) Initial motions in Saatchi’s lawsuit against Burns have already been filed. If the case comes to trial, Saatchi insiders loyal to Burns say that General Mills may be unamused when it finds out how much of Saatchi’s profit line is supported by the margins on General Mills’ accounts. The Saatchi 17, meanwhile, have named their new Interpublic venture Project Pilgrim, a jab at what they perceive to be Roberts’s management-by-persecution style. So far, they have no known clients. Which raises a still-unanswered question: Did Mike Burns and the Saatchi 17 leave the agency because of their clash with Kevin Roberts, or was it part of a master plan to pull off the biggest heist in advertising history?

On a recent Monday morning, Kevin Roberts sits behind his sleek modern desk in the Saatchi & Saatchi offices on Hudson Street, near Canal, a giant movie poster from Gladiator, signed by Russell Crowe, looming behind him. Roberts’s chair is elevated; visitors sit a time zone away. The office aesthetic mirrors that of his Tribeca apartment, a minimalist condo without doorknobs or levers of any kind (the lack of an obvious flushing device so baffled Saatchi staffers during one dinner party that the toilet backed up).

Roberts is on the phone when I come in. Soon, he’s smiling and pumping his fist. “Hey, can I tell a reporter?” he asks. The other voice says no, and Roberts’s face falls a bit. Then he hangs up and the smile returns. (Tomorrow it would be announced that Saatchi & Saatchi had won a $55 million account from American Express Financial Advisors.) “We would have never got this account under our old team,” says Roberts, offering me an aggressive handshake.

Roberts quickly detours from my first question. “I doubt you’re at your best, dressed so sharply, wearing this beautiful tie,” he says. “I just doubt it. I look at your hairstyle and I see incongruency here. You have a free-flowing, radical haircut, and you’ve got this suit on. I bet you’d be a better interviewer when you’re in your casual clothes, whether Ralph Lauren or Armani.” Roberts then tells me about a company-sponsored tsunami-relief contest. The young staffers who raised the most money won the grand prize of a dinner with Roberts (another prize was an oil painting of Roberts). “Kids today aren’t looking for careers,” he says, pounding his fist into his hand. “They are looking for experiences. I like that.”

Roberts shares a brief history of his time at the company, as he sees it. When he took over, he says, “it was clear where the business was going. There was going to be four big holding companies and six niche agencies, and anything in the middle was going to be dead. We were in the middle.” Under Roberts, Cordiant spun off Saatchi & Saatchi back into its own entity, and new financing was generated by selling stock to staffers at a discount. Roberts moved the agency’s headquarters from London to New York. He implemented the strategy of winning more business from the agency’s core clients and announced he had two secret weapons for revitalizing Saatchi & Saatchi creatively: Lovemarks and Peak Performance.

When the subject turns to Burns, Roberts speaks for more than an hour. During that time, he professes bewilderment and hurt over Burns’s departure, insists he tried to make things work with him, and, yet, maintains he did the right thing by suing him. “I always liked Mike,” he says. “I wanted to make this a family, but I was sitting outside of it. I was not the father or even the godfather or uncle or grandfather, and it didn’t work.”

In 2001, Roberts says, he offered to make Burns CEO of Saatchi Australia, a move, he says, that would have given Burns more seasoning. “I thought he could build on his skills in Australia, and it would take him away from his self-imposed baronial fiefdom.” After Burns lost his CEO position, Roberts offered him the position of co-chairman, a largely ceremonial title.

When I ask Roberts why he chose to sue Burns, he grimaces. “I was taught you have to do what is right when no one is looking,” he says. “I believe there has been a breach of fiduciary duty by Mike.” As I say my good-byes, Roberts mutters, “Mike Burns—it must be that Irish blood.”

Roberts’s journey from Lancashire, England, to CEO of one of the world’s largest and most prestigious ad firms borrows from both Horatio Alger and Alfie. Roberts’s father was an orderly at a psychiatric hospital, and his mother worked in a greeting-card shop. In school, he excelled in rugby and cricket, but he “was too much of a rebel” to earn honors like being named a prefect. When he announced at 14 that he would be a millionaire before he turned 30, his classmates laughed him out of the room.

At 17, Roberts fathered a girl with a high-school sweetheart. The couple later married, and the family moved to London, where Roberts blustered his way into Mary Quant cosmetics just as the hip boutique was branching into Europe. Roberts persuaded management to hire him as a brand rep, despite having no experience, by offering to work for six months at half-pay. Quant prospered, and so did Roberts (he and his first wife eventually divorced, and he married a Quant model. They’re still together and have their own children; he sees his first daughter regularly). “It was the first time I had money in my pocket,” he says. “I felt I could accomplish things.”

The Saatchi 17 deny they intended to take General Mills. Their argument is simple: We are not stupid enough to think seventeen people could steal a half-billion dollars in business.

Roberts next spent three years with Gillette, marketing women’s toiletries, before going to work for Procter & Gamble as chief of Middle East marketing. “I learned how products can change the world,” says Roberts, who lived in Casablanca. “Before we got there, they had never seen detergent and shampoo. Lives were changed.” By 29, Roberts had made the million he had boasted he’d make with a year to spare.

In 1982, Roberts went to work for Pepsi, first in the Middle East, and later was named president and CEO of Pepsi Canada. Taking what he learned from P&G, he demanded his colleagues not just sell Pepsi but love it. If you hated Coke, that helped, too (witness the machine-gun stunt).

Roberts spent the next seven years as head of Lion Nathan, a New Zealand brewery, moving the company into international markets including China, with unremarkable results. Profits stagnated, and between 1995 and 1996, Lion Nathan lost nine executives in one eighteen-month period. Roberts resigned.

At about the same time, Saatchi was looking for a new CEO. Kevin Roberts knew Saatchi’s operation from his days with Procter & Gamble, a longtime Saatchi client, and had since become friends with then-CEO Ed Wax. Wax was impressed with Roberts’s energy and brand-love theories. In May 1997, he offered Roberts the job.

Shortly after I met Mike Burns, he invited me to his Greenwich Village apartment, ten blocks from Saatchi headquarters. The apartment is a large, pleasant one-bedroom in a five-story building; he also owns a home in Sagaponack (when Burns left Saatchi, he was earning $1 million a year). As we were getting acquainted, his phone rang. It was the Minneapolis Club, the posh hotel he called home on his trips to Minnesota. “No, I probably won’t be coming anytime soon,” he said. “Yes, you can let my membership lapse. Talk to Saatchi & Saatchi about any outstanding bills.”

The irony of Mike Burns’s battle with Kevin Roberts is that they believe in many of the same things; they just use different words. Burns talks about Cheerios as if it were, well, a Lovemark. “Cheerios is about the circle of life,” Burns says, dressed in sandals and tanned from a weekend at his Hamptons house. He’s got classic Irish features—reddish-blonde hair, a ruddy complexion—and looks younger than his 48 years. “It’s the first finger food you eat when you’re 2, and it’s maybe the last food you eat when you’re 72 because it’s great for your heart.”

Burns tries to get comfortable on his couch, then stands up. “My lawyer is having a fit that I’m even talking to you,” he says. He is severely limited in what he can divulge about his departure from Saatchi because of the pending lawsuit. What he will say is that he loved General Mills. “They have these incredibly sophisticated and competitive marketing people,” he says. “Think about the categories they’re in. Basically, it’s a grain company, whether breakfast cereals or Hamburger Helper or granola bars. It’s all flour. Their ability to create consumer value and brand distinctions is unparalleled.”

Burns is the first white-collar professional from a Bronx family of cops and firemen and city schoolteachers. After graduating from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, he landed at Dancer Fitzgerald. A year after starting, Burns had a heart attack at age 24. He was out of work for two months. “One of the things that really motivated me was a feeling I could never catch up from that,” says Burns. “I didn’t take a vacation for years.”

Around the time Burns returned from medical leave, 60 Minutes had just done a segment damning the food industry, including cereal makers, for the impact of sugar on kids. General Mills thought a product called Honey Nut Cheerios might appeal to the health-conscious mom. The idea was that honey and nuts had a more wholesome image than sugar, says Burns. To any kid growing up in the eighties, the Honey Nut Cheerios honeybee rivaled Cap’n Crunch for Saturday-morning ubiquity. By the end of the eighties, Brandweek had named Honey Nut Cheerios the “emerging brand of the decade.” Now it’s the country’s second-best-selling cereal, after original Cheerios.

In 1988, Burns and his colleagues created Kid Connection, a division within Dancer Fitzgerald. The thinking (then novel, now practiced by everyone) was that ads could target kids—the real purchasing decision-makers—not moms. The group employed child psychologists and anthropologists. Today, it still exists within Saatchi as the largest children’s-advertising resource in the business.

Burns and his crew had survived the purchase of Dancer Fitzgerald by Saatchi & Saatchi and the dumping of Maurice and Charles Saatchi. Then came Kevin Roberts.

From the wardrobe and the sermons alone, it was clear from Roberts’s first meeting with Saatchi’s New York office that a change agent was in the house. “This might be Saatchi & Saatchi, but its roots were still in the Wasp school of advertising,” says a longtime Saatchi staffer. “You never heard a curse word, you were as kind to the janitor as you were to the account executive. A lot of people were going, ‘What the hell is this man talking about?’ ”

Roberts’s first major initiative was to focus more on Procter & Gamble, the client he knew well. P&G was 30 percent of Saatchi’s American billing, and it represented an even larger share of Saatchi’s global revenue than General Mills. Still, in New York, General Mills had always been the star client. Roberts gave a series of presentations in 1998 stating that P&G was to become a top priority.

“It was, ‘If you work on P&G, you’ll get what you need,’ ” says a longtime Saatchi staffer who is agnostic in the Roberts-Burns feud. “Suddenly, if people on P&G said, ‘I need a new computer,’ you got a new computer. If you needed something that would have you do better at your job, you got it overnight. The effect was that General Mills wasn’t the only kid on the block that could strut its stuff.”

Inevitably, a rivalry developed between the General Mills and P&G cliques. Up-and-comers at the agency no longer automatically gravitated to Burns and his GM team. “People wanted to work on P&G because they knew they would get access to Kevin,” says a former Saatchi executive with no allegiance to either Burns or Roberts. “If you were on P&G, you could go to Kevin and say, ‘We need people on Oil of Olay or we’re going to lose it,’ and he’d put an army on it. On General Mills, he’d shrug and say, ‘Talk to Mike.’ But there was always a smaller profit margin on P&G because Kevin just threw resources at it until the goal was reached.” Roberts calls the profit-margin claim “nonsense.” “In the eight years I’ve been here, we’ve had our best people on General Mills. I didn’t get one call from the client saying they were underserved. Why would they have hired us to do Pillsbury in 2001 if they thought they were underserved?”

By 2002, Saatchi & Saatchi had become one of advertising’s Big Four—the linchpin of the French conglomerate Publicis’ advertising empire—as Roberts had intended. When Publicis purchased Saatchi in 2000, the employee-purchased stock was redeemable at five times its original value. The firm won the Ad Age agency-of-the-year honor in 2002. In addition to his $2 million salary, Publicis paid Roberts a reported $1.9 million as part of the takeover.

A good sign of the communication breakdown between Roberts and the General Mills team involves their interpretation of terms. Shortly after taking over Saatchi, Roberts created what he called the K-7 board, to oversee the company’s international operations. Made up in part of friends of Roberts’s, the K-7, Roberts says, was named after a New Zealand America’s Cup boat. Inside Saatchi, a different legend grew. “The board is called K-7 for Kevin-7,” says a former General Mills staffer. “Seven people in service of Kevin.”

Roberts’s Peak Performance seminars were another sore spot for his detractors. He began selling them to Saatchi clients (some say his daily consulting fee ran near $100,000 a day, a figure he denies). The seminars ran under the auspices of a company called Inspiros, but shareholders included Roberts and his K-7 buddies. Critics claimed Roberts was using his position at Saatchi for personal gain.

Then there was the 9/11 memo. Forty-eight hours after the attacks, Roberts sent a note that seemed to blur the line between the gravity of the day’s events and the importance of Saatchi’s business:

“I am writing this letter from the 16th floor of Saatchi & Saatchi … The sky is black with smoke, the streets are quiet except for rescue vehicles’ sirens, our building is cordoned off; the overwhelming feeling is one of emptiness … The only response from an Ideas Company is to help rebuild confidence through contributing and implementing ideas for our clients and our communities. Two of the key principles we believe in at Saatchi & Saatchi are entirely aligned with these values and qualities: Peak Performance and Lovemarks.

“Peak Performance. We need inspiration. It’s the time for inspirational players. It’s time also for America to remember its founding dream, a nation dedicated to freedom and opportunity and innovation. This will also be a time for inspirational stories of heroism and sacrifice: fire captains and police, co-workers and medics.

“Lovemarks. For many of us, this attack has been an attack on a Lovemark: New York … Lovemarks are a fitting message for uncertain times, an antidote to the nervousness and panic that will affect American business globally … Lovemarks are an expressive language for renewed feelings of national worth … ”

“It was so crass,” recalls a former Saatchi executive. “There was just stunned silence as we showed it to each other.”

Roberts grew increasingly frustrated with Burns’s reluctance to seek his input, and repeatedly urged him to work more in concert with him and other agency managers. Burns responded that he was running an account with 43 advertised brands and 100 commercials a year, airing in 73 countries—he didn’t have time to stroke Roberts. Burns and the General Mills crew felt it was their account’s steady profitability that funded the agency’s turnaround, but they weren’t sharing in the profits. “There were many years where the agency was in a chronic pattern of salary, wage, and hiring freezes,” says a former Saatchi staffer on General Mills. “If someone left General Mills, we couldn’t get them replaced. Then Kevin would come into a room and talk about the big bonuses he’s getting from [Publicis CEO] Maurice Levy. ‘Oh, man, I squoze [sic] his fuckin’ balls! He signed me up for three more years!’ But you’re sitting there like, ‘Shit, man. I can’t get raises for people, and you’re talking about big bonuses.’ It just didn’t make any sense.” (Roberts stands by his profit-margins denial.)

Using his K-7 management team as a model, Roberts installed an eight-person board of directors to run Saatchi’s New York office in 2000. The directors included Burns, the account executives of Saatchi’s other major clients, and various department heads. It quickly became unmanageable. “There’s a reason why communism failed,” quips one former member. “Everyone had their fiefdoms to protect and couldn’t see above that. And Kevin still had final say. If you wanted to paint a conference room, you were empowered. If there were people that needed to be laid off, you were empowered. Anything else, you had to wait for Kevin.” Not true, says Roberts: “I oversee 92 offices. I didn’t personally manage New York.”

In an echo of Roberts’s experience at Lion Nathan, there were twelve members of the New York Saatchi board in seven years. “It wasn’t just attrition,” says a former board member. “You left because Kevin voted you off the island.” By late 2003, the board had been reduced to two—Burns and Scott Gilbert, who had run Saatchi’s L.A. office. While Burns and Roberts often squabbled, Roberts thought enough of Burns to make him co-CEO. The arrangement didn’t last. “Kevin came in and said, ‘Okay, you two guys are going to be co-CEOs,’ ” recalls Burns with some bewilderment. “But he was going to oversee us. This was in December, but by late January he was like, ‘You know what? This doesn’t work.’ ”

Roberts concedes the eight-man management board was “a big mistake.” But he stands by his decision to take away the CEO title from Burns. “Mike’s weakness is that he was a classic account guy driven by his own client, and he would deliver within those boundaries,” says Roberts, who insists he gave the experiment six months. “Being a CEO is about paradox. Mike was about either-or; General Mills or nothing. Mike put up barriers; Scott couldn’t break through. People sided with either A or B. I decided to put an end to it.”

Roberts believed the agency’s relationships with its major clients had been solidified—it was time to go after new business. A sole CEO in New York would finally be hired. At the same time, worldwide creative director Bob Isherwood had grown dissatisfied with New York creative director Tod Seisser over the agency’s failure to win industry awards. Roberts agreed. (This was about the same time that Roberts approached Adriance about being head of HR.) After several months, Roberts settled on Mary Baglivo, a longtime Procter & Gamble associate, as his CEO. Seisser would be fired, and London creative director Tony Granger would take over New York.

Burns was furious that he wasn’t brought into the loop until the night before the September 14 meeting. “I sat there at that point and I said to myself, ‘This isn’t where I want to be,’ ” he says. “I was there for 25 years. I ran 50 percent of the agency. So here’s news that the creative director who’d worked with all of my clients was being let go and nobody told me about it? You’re not going to tell me who the new people are because you’re worried about press leaks? I wasn’t able to inform my clients. I wasn’t able to inform the folks that I work with. It was a carnival act of epic proportions.”

After the meeting, Burns sent an e-mail to Roberts outlining his dissatisfaction. Roberts said he might be able to get Burns a salary bump. Burns said he was concerned not about his own salary but about how his team was being treated. He never got a response.

By the time Burns handed in his resignation on February 11, Roberts and Baglivo were expecting it. Negotiations over Burns’s multi-million-dollar separation package had been ongoing and largely amicable.

The Saatchi 17, meanwhile, had kept their plans an airtight secret. Many of the senior members of the group spent their last day at Saatchi attending a leadership-committee meeting chaired by Mary Baglivo. “Several of the General Mills people were there, actively participating,” recalls Baglivo. “It was very nice.”

Baglivo left early that day because it was her daughter’s birthday. At 5:30, she received a call from a frantic HR staffer: Seventeen members of the General Mills team had just quit.

Ironically, the Saatchi 17’s departure was made easier because none of them had service contracts, rare for senior executives like Adriance. “That was a real blunder by Kevin. He thought it allowed him to get rid of them when he wanted. I don’t think he ever thought they would turn it to their advantage,” says a Saatchi insider. “That’s why he can’t sue them.”

Within hours, rumors circulated through the ad world that the seventeen weren’t just leaving; they were going to be hired en masse by Interpublic, a rival conglomerate, and a celebratory dinner was going to be held later that week at ‘21.’ Roberts, who was in Tokyo at the time, caught a flight to Minneapolis and General Mills’ headquarters to speak with Steve Sanger (that Friday, General Mills issued a statement: “We continue to be very pleased with Saatchi’s work on our behalf, and we are looking forward to continuing our 80-year relationship”), then flew back to New York and ordered some of the remaining General Mills staffers to be questioned by company lawyers with a stenographer present.

By Thursday, the seventeen staffers had agreed to join Interpublic but didn’t sign contracts. General Mills, sensing an opening, appealed to Roberts and Adriance to seek a rapprochement. Almost all of them came in for informal meetings, but Roberts assigned the interviews to subordinates and refused to let anyone talk to Adriance.

The meetings were supposed to be secret, but the next morning Roberts announced to Saatchi staffers, “I’ll only take them back if they’re innocent of the conspiracy, committed to Saatchi, and they apologize.” He then released a statement to the press saying, “We will be reviewing whether any of the 17 ex-colleagues have a role to play going forward.” Going public with the meetings hadn’t been part of the deal, and any window of opportunity quickly closed.

On March 10, the Saatchi 17 officially joined Interpublic (so far, neither they nor the agency will say what they’re working on or even if they have clients). The next day, Saatchi sued Burns, requesting an injunction preventing Burns from “directly or indirectly launching any company or taking employment with any advertising, marketing, or communications company which services [General Mills].” All the while, Mike Burns remained silent.

Clad in a navy Lacoste shirt and shorts, Mike Burns putters around his Sagaponack home on a brilliant June Sunday. His girlfriend, Merrie Harris, and her daughter lounge by the pool (Harris runs the Pampers account for Saatchi). Burns says he’s more than a little depressed that his 76-year-old mother is now reading in the Wall Street Journal how her son tried to steal business. “This is how most of the world knows me now.”

Although Burns and the Saatchi 17 won’t speak for attribution on the question, they strenuously deny that their goal was to leave and take General Mills with them. Their argument is simple: We are not stupid enough to think seventeen people could steal a half-billion dollars in business. Many of the seventeen had their résumés and reels on the street months before their departure, they say. The reason they departed en masse, they contend, was simply that Interpublic gave them the opportunity to keep their close-knit team together.

Maybe, but Interpublic must have thought they could get a few General Mills crumbs. “Most of the people who left were General Mills cereal people,” says a former Saatchi executive. “It suggests they thought they could get a piece of Cheerios. I don’t think Interpublic is going to spend millions in salary without thinking they are going to get some of Cheerios in return. And it’s hard to believe that Anne [Adriance] would do this without talking to Mike. I don’t know that she did, but it doesn’t follow.”

Another insider with intimate knowledge of the Saatchi 17 situation spins a slightly more benign scenario: “Interpublic knew about the clash between Kevin and Mike and what that might mean to General Mills. They knew GM might grow frustrated and put part of their cereal accounts out to bid. Wouldn’t you want to be the agency that had a team GM was already comfortable with in your stable?”

Toward the end of my reporting, I finally met with Anne Adriance, Mike Burns’s confidante and now the leader of the breakaway seventeen. It was the first time she had spoken publicly about the ordeal. A fortysomething woman, she carries herself with a quiet presence and speaks in a small voice. It’s not hard to imagine her and Kevin Roberts clashing. “I think Kevin has enormous strengths, and up to a point I was always ready to fall in line,” Adriance says. “But at the end of the day, it’s people like Mike who walk the talk, and did that long before it became some glitzy little thing you could package with a trademark-registered R next to it.”

She picked at her salad and gazed around Bryant Park as if wondering if someone were watching us. “People don’t get up and walk away from a client they love, a company they’ve been loyal to, a team they feel fabulous about working with, because things are going the way they think they should. There comes a point where you can no longer bite your tongue, suck it up, and play the game when you know the way things should be done that are better, and it’s not to be disloyal. It’s to work to a common goal.” Later, I ask her if there’s validity to the claim that she and the others intended, or intend, to poach General Mills business. “That was never our intention, but I can’t talk about that because of the lawsuit,” she says.

Out in Sagaponack, Mike Burns smiles wearily when I tell him of his friend’s words. “The only thing Anne and the Saatchi 17 wanted to take from Saatchi when they left was their dignity,” says Burns. He walks out on to his porch and looks toward his pool and garden. “Look, everything I have is because of General Mills and Saatchi. I want them both to succeed. We’ll all be better off when this suit is behind us.” He then gives me an adman’s smile, and tries to sell the unsellable. “I like Kevin. I really do.”